50 Years of Mining History – Memoirs 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walk Into History

Walk into History A series of walks curated by Swaledale Museum The Green Reeth DL11 6TX 01748 884118 www.swaledalemuseum.org Walk 7 Chapels of Arkengarthdale Total Distance: 5.25 miles / 8.5 km Total Ascent: 500 ft / 155m Approx Time: 2.5 – 3 hrs Grade: Easy Chapels of Arkengarthdale (easy) An exploration of Arkengarthdale’s history of non-conformism is a perfect way to take in its scenery, via riverside meadows, a delightful section of quiet, elevated single-track road and the much- filmed village of Langthwaite. Start Car Park in Langthwaite, just S of bridge Grid Reference: NZ 00522 02303 Refreshments Pubs in Langthwaite Historical Photos Langthwaite, Eskeleth © OpenStreetMap contributors 6 E D 5 F G 7 8 4 C 9 3 2 B 10 A H 1 1 Turn R out of the car park, passing bridge on R, cluster of houses and then war memorial on L. 2 Fork R to pass in front of St Mary’s Church, and continue along Scar House drive. 3 Just beyond West House (with its sundial) on R, fork L across grass to stile. Turn L, then shortly R to keep on track that leads across fields to road. 4 Cross the ‘Stang’ road and take footpath opposite signposted ‘Whaw’. After 100m, cross footbridge on R then turn half L to a stile. From here, continue with river on L for 1.8km to Whaw. 5 Pass through gate then continue along road with river still on L, passing Whaw on R. When the road bends steeply up to R, keep with it. -

Happy Easter to All from Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 193 APRIL 2012 Happy Easter to all from your local news magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD CHURCH NOTICES in Swaledale & Arkengarthdale st 1 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist - Palm Sunday 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist 11.00 am Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist St. Edmund’s Marske Reeth Evangelical Congregational Eucharist 2.00 pm Keld URC 6.00 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton Evening Prayer BCP 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist Reeth Evangelical Congregational th 5 April 7.30 pm Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist & Watch 8.00 pm St. Michael’s Downholme Vigil th 6 April 9.00 am Keld – Corpse Way Walk - Good Friday 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational 12.00 pm St Mary’s Arkengarthdale 2.00 pm St. Edmund’s Marske Devotional Service 3.00 pm Reeth Green Meet 2pm Memorial Hall Open Air Witness th 7 April – Easter Eve 8.45 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton th 8 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s, Muker Eucharist - Easter Sunday 9.30 am St. Andrew’s, Grinton Eucharist St. Michael’s, Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Low Row URC Holy Communion Reeth Methodist All Age Service 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s Marske Holy Communion Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist 11.15 am St Mary’s Arkengarthdale Holy Communion BCP 2.00 pm Keld URC Holy Communion 4.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational Family Service followed by tea 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist with Gunnerside Choir Arkengarthdale Methodist Holy Communion th 15 April 9.15 am St. -

Grade 2 Listed Former Farmhouse, Stone Barns

GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an Rare development opportunity in a soughtafter location. Situation Swale Farmhouse is well situated, lying within a soughtafter and accessible location occupying an elevated position within Swaledale. The property is approached from a private driveway to the south side of the B6260 Richmond to Reeth Road approximately 8 miles from Richmond, 3 miles from Reeth and 2 miles from Grinton. Description Swale Farmhouse is a Grade 2 listed traditional stone built farmhouse under a stone slate roof believed to date from the 18th Century with later 19th Century alterations. Formerly divided into two properties with outbuildings at both ends the property now offers considerable potential for conversion and renovation to provide a beautifully situated family home or possibly multiple dwellings (subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents). The house itself while needing full modernisation benefits from well-proportioned rooms. The house extends to just over 3,000 sq ft as shown on the floorplan with a total footprint of over 7,000 sq ft including the adjoining buildings. The property has the benefit of an adjoining grass paddock ideal for use as a pony paddock or for general enjoyment. There are lovely views from the property up and down Swaledale and opportunities such as this are extremely rare. General Information Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves The property is sold subject to, and with the benefit of all existing wayleaves, easements and rights of way, public and private whether specifically mentioned or not. -

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Self-Guided Walking Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: MDPXA-7 1, 2, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy a festive break in the Yorkshire Dales with the walking experts; we have all the ingredients for your perfect self-guided escape. Newfield Hall, in beautiful Malhamdale, is geared to the needs of walkers and outdoor enthusiasts. Enjoy hearty local food, detailed route notes, and an inspirational location from which to explore this beautiful national park. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The use of our Discovery Point to plan your walks – maps and route notes available www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Use our Discovery Point, stocked with maps and walks directions, for exploring the local area • Head out on any of our walks to discover the varied landscape of the Southern Yorkshire Dales on foot • Enjoy magnificent views from impressive summits • Admire green valleys and waterfalls on riverside strolls • Marvel at the wild landscape of unbroken heather moorland and limestone pavement • Explore quaint villages and experience the warm Yorkshire hospitality at its best • Choose a relaxed pace of discovery and get some fresh air in one of England's most beautiful walking areas • Explore the Yorkshire Dales by bike • Ride on the Settle to Carlisle railway • Visit the spa town of Harrogate TRIP SUITABILITY Explore at your own pace and choose the best walk for your pace and ability. -

Apcmin 180917 1 ARKENGARTHDALE PARISH

APCmin_180917 1 ARKENGARTHDALE PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of a meeting of Arkengarthdale Parish Council held at Arkengarthdale Church of England Primary School Monday 17 September 2018 at 8.00pm MINUTES Present: Councillor S Stubbs (Chair); Councillor P Lundberg (Vice-Chair); Councillor J Watkins; Councillor P Harker; Councillor R Stones In attendance: S Dray (Clerk to the Parish Council) Apologies for Absence: Councillor J Blackie; Councillor I Scott 14/18 Declarations of interest There were no declarations of interest relating to the meeting agenda. 15/18 Minutes The minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on Monday 23 July 2018 was confirmed as a correct record by the Council and signed by the Chair. 16/18 Matters arising There were no matters arising not otherwise on the agenda. 17/18 Planning Applications The Council noted the conditional approval of application R/01/159 at Fairhaven, Booze, and considered the following new planning applications: 17.1 R/01/160 - Fairview, Booze. The Council fully supported this application, noting that the proposed work would not impact visually on the dale, being hidden from view, and made good use of existing facilities; 17.2 R/01/161 – Affordable Housing, Arkengarthdale. The Council fully supported this application, noting that the new houses would encourage young families to live in the dale. 18/18 Interpretation Board The Council received a report from Coun. Lundberg on the stand for the board, which would be sourced and made locally from green oak. The supplier would require the board from the National Park in order to produce the stand. The National Park would be contacted.[Action JW] 19/18 GDPR The Council considered the requirements for compliance with the new EU General Data Protection Regulation legislation noting that, although small parish councils were exempt from much of the legislation, it would nevertheless be prudent to install additional antivirus software on the Council’s IT equipment. -

Mould Side: Lead, Chert and Grit – a Circular Walk

Mould Side: Lead, Chert and Grit – a circular walk About 3.8 miles / 6.1 km or 3-4 hours when you stop and look at the landscape. Good walking boots and appropriate clothing is essential. There are several short sections usually no more than 20 metres in length, which are steep climbs or decents of grassy banks. You can usually zig-zag up these. Walking down Stoddart’s Hush requires walking of rocks but this isn’t very difficult other than choosing your path over the rocks. Stoddart’s Hush, by far the most spectacular hush to visit, is one of those ‘off the beaten track’ places which is well worth the effort of getting there. I have placed all the photographs at the end of this document, so that you can just print the front 5 text pages of the guide to take with you. Location: From Reeth turn by The Buck Hotel to go up Arkengarthdale. Between the village of Langthwaite and the CB Inn turn left towards Low Row (sign post = Low Row). The lane climbs up hill passing some large lead mining spoil heaps. Just passed the last spoil heap the lane continues to climb, but after approximately 200m it passes over a flat bridge with stone side-walls, located at the bottom of Turf Moor Hush. Park either side of this bridge on the grass verge. There is plenty of room for many cars. Route: Using your GPS follow the route up Turf Moor Hush. The first 20 minutes is all up hill. About 75-80% of the hill climbing is done whilst your are fresh. -

FOR SALE CAMBRIDGE HOUSE £799,950– Freehold ARKENGARTHDALE ROAD, REETH, RICHMOND, DL11 6QX CAMBRIDGE HOUSE, ARKENGARTHDALE ROAD, REETH, RICHMOND DL11 6QX

FOR SALE CAMBRIDGE HOUSE £799,950– Freehold ARKENGARTHDALE ROAD, REETH, RICHMOND, DL11 6QX CAMBRIDGE HOUSE, ARKENGARTHDALE ROAD, REETH, RICHMOND DL11 6QX SUMMARY • Five Star Gold Luxury B&B • Outstanding trading position in the Yorkshire Dales National Park • Tremendously popular walking, cycling and touring area • Excellent facilities, beautifully appointed and very good accommodation for owners • Garden, gated car park and garaging with secure cycle storage • Award winning business, attractive lifestyle and glorious views. INTRODUCTION Cambridge House is a high quality B&B with outstanding National Park trading location, beautifully appointed facilities, excellent accommodation for owners, a strong and profitable business and glorious views from just about every window. The owners acquired Cambridge House in 2013 and have thoroughly enjoyed operating the business and living in such a beautiful part of the country. They have nurtured the business and reinvested income to keep the property and facilities in first class condition and have even created a new en suite bedroom. Now, having operated Cambridge House as a pre- retirement venture, they are ready to move on to the next stage of their lives, hence the opportunity to acquire an outstanding B&B business and home offering an attractive mix of lifestyle and income. LOCATION Situated on the outskirts of the popular village of Reeth, Cambridge House has a superb B&B location with wonderful walks from the doorstep and easy access to numerous eateries in the village and surrounding Dales. The whole area is perfect for walking and the famous Coast to Coast walk passes through the village. As well as being a popular walking area, Reeth is a cycling haven and even has it’s own mountain biking festival which is extremely popular. -

Ingleton National Park Notes

IngletonNational Park Notes Don’t let rain stop play The British weather isn’t all sunshine! But that shouldn’t dampen your enjoyment as there is a wealth of fantastic shops, attractions and delicious food to discover in the Dales while keeping dry. Now’s the time to try Yorkshire curd tart washed down with a good cup of tea - make it your mission to seek out a real taste of the Dales. Venture underground into the show caves at Stump Cross, Ingleborough and White Scar, visit a pub and sup a Yorkshire pint, or learn new skills - there are workshops throughout the Star trail over Jervaulx Abbey (James Allinson) year at the Dales Countryside Museum. Starry, starry night to all abilities and with parking and other But you don’t have to stay indoors - mountain Its superb dark skies are one of the things that facilities, they are a good place to begin. biking is even better with some mud. And of make the Yorkshire Dales National Park so What can I see? course our wonderful waterfalls look at their special. With large areas completely free from very best after a proper downpour. local light pollution, it's a fantastic place to start On a clear night you could see as many as 2,000 your stargazing adventure. stars. In most places it is possible to see the Milky Way as well as the planets, meteors - and Where can I go? not forgetting the Moon. You might even catch Just about anywhere in the National Park is great the Northern Lights when activity and conditions for studying the night sky, but the more remote are right, as well as the International Space you are from light sources such as street lights, Station travelling at 17,000mph overhead. -

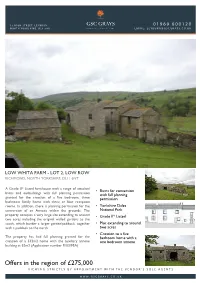

Offers in the Region of £275,000 Viewing Strictly by Appointment with the Vendor’S Sole Agents

15 HIGH STREET, LEYBURN 01969 600120 NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL8 5AQ EMAIL: [email protected] LOW WHITA FARM - LOT 2, LOW ROW RICHMOND, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL11 6NT A Grade II* Listed farmhouse with a range of attached • Barns for conversion barns and outbuildings with full planning permission with full planning granted for the creation of a five bedroom, three permission bathroom family home with three or four reception rooms. In addition, there is planning permission for the • Yorkshire Dales conversion of an Annexe within the grounds. The National Park property occupies a very large site extending to around • Grade II* Listed two acres including the original walled gardens to the south, which border a larger garden/paddock, together • Plot extending to around with a paddock to the north. two acres • Creation to a five The property has had full planning granted for the bedroom home with a creation of a 332m2 home with the auxiliary annexe one bedroom annexe building at 62m2 (Application number R/03/95A) Offers in the region of £275,000 VIEWING STRICTLY BY APPOINTMENT WITH THE VENDOR’S SOLE AGENTS WWW. GSCGRAYS. CO. UK LOW WHITA FARM - LOT 2, LOW ROW RICHMOND, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL11 6NT SITUATION AND AMENITIES The farmhouse is situated in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales National Park in Swaledale, on the southern side of the River Swale. The property is equi-distant between Healaugh and Low Row. The town of Reeth is situated approximately 5 miles away which is well served with a primary school, Doctors' survery, local shop, tea rooms, public houses and the Dales Bike Centre. -

Swaledale Museum Newsletter 29 Spring 2020 Print

Newsletter No.29 Spring 2020 A message from the Curator As I write this, in mid-April, I am hoping that we will be able to resume ‘service as normal’ in the Museum this season. However any forward planning has become an almost impossible task as the situation changes from week to week. Ever the optimist I have decided to assume that we will be re-opening on 21st May and be running our programme of events. However, checking ahead will be paramount as we adapt to the latest guidelines. One of the benefits of the lockdown has been longer and more considered messages between Lidar image of Reeth - thanks to Stephen Eastmead acquaintances. I have, for example, been receiving regular pages from an ‘electronic diary of the plague marginalia in much loved and favourite books. months’ from an elderly friend living in a small hamlet. What sort of evidential trail are we leaving behind He wonderfully captures how small things have acquired us now, that will reflect what the Dale, the country greater meaning and value. I have been reading Jared and the world has gone through? How will curators Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday (2012) in which in the future present these episodes to the public? he compares how traditional and modern societies cope What projects are already in the making to tell the story of how we all reacted and coped? with life, looking at peace and danger, youth and age, language and health. He asks what can we learn from A severe blow to us all has been the loss of Janet ‘traditional’ societies? This spurred me to think about Bishop, Chairman of the Friends of the Museum. -

Swaledale and Arkengarthdale Archaeology Group West Hagg Site

on behalf of Swaledale and Arkengarthdale Archaeology Group West Hagg Site 103 Swaledale North Yorkshire archaeological excavation report 3101 March 2013 Contents 1. Summary 1 2. Project background 2 3. Landuse, topography and geology 2 4. Circumstances of the project 3 5. The excavation 3 6. The artefacts 8 7. The palaeoenvironmental evidence 15 8. References 17 Appendix 1: Stratigraphic matrices 19 Appendix 2: Data tables 21 Appendix 3: Iron artefact catalogue 23 Figures Figure 1: Site location Figure 2: Location of trenches in relation to earthwork survey and geophysical interpretation Figure 3: Location of trenches in relation to geomagnetic survey and resistivity survey Figure 4: Plan of flagged surface, Trench 1 Figure 5: Plan of the demolition phase, Trench 1 Figure 6: Plan of Trench 2 Figure 7: Profiles and section of Trench 2 Figure 8: Section and plan of Trench 4 Figure 9: Pottery Figure 10: Artefacts Figure 11: Trench 1, looking south‐east Figure 12: Trench 1, looking east from the intersection with the southern extension, with the door‐sill F111 in the foreground Figure 13: Trench 1 southern extension, looking north‐east along the line of the possible path Figure 14: Trench 1, reconstructed door‐sill F111 Figure 15: Trench 2, SWAAG members at work cleaning up the roundhouse Figure 16: Trench 2, the roundhouse, looking south‐west Figure 17: Trench 2, the door‐sill F225, looking east Figure 18: Trench 2, the north‐western side of the roundhouse Figure 19: Trench 3, looking north‐west Figure 20: Trench 4, looking south‐west © Archaeological Services Durham University 2013 South Road Durham DH1 3LE tel 0191 334 1121 fax 0191 334 1126 [email protected] www.dur.ac.uk/archaeological.services West Hagg Site 103· Swaledale· North Yorkshire· archaeological excavation· report 3101· March 2013 1. -

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale The two far northern dales, with their The River Swale is one of England’s fastest industry, but in many places you will see iconic farming landscape of field barns and rising spate rivers, rushing its way between the dramatic remains of the former drystone walls, are the perfect place to Thwaite, Muker, Reeth and Richmond. leadmining industry. Find out more about retreat from a busy world and relax. local life at the Swaledale Museum in Reeth. On the moors you’re likely to see the At the head of Swaledale is the tiny village hardy Swaledale sheep, key to the Also in Reeth are great shops showcasing of Keld - you can explore its history at the livelihood of many Dales farmers - and the local photography and arts and crafts: Keld Countryside & Heritage Centre. This logo for the Yorkshire Dales National Park; stunning images at Scenic View Gallery and is the crossing point of the Coast to Coast in the valleys, tranquil hay meadows, at dramatic sculptures at Graculus, as well as Walk and the Pennine Way long distance their best in the early summer months. exciting new artists cooperative, Fleece. footpaths, and one end of the newest It is hard to believe these calm pastures Further up the valley in Muker is cosy cycle route, the Swale Trail (read more and wild moors were ever a site for Swaledale Woollens and the Old School about this on page 10). Gallery. The glorious wildflower meadows of Muker If you want to get active, why not learn navigation with one of the companies in the area that offer training courses or take to the hills on two wheels with Dales Bike Centre.