Fireworks Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Bainbridge Island 2020 Lodging Tax / Tourism Fund Proposal Cover Sheet

CITY OF BAINBRIDGE ISLAND 2020 LODGING TAX / TOURISM FUND PROPOSAL COVER SHEET Project Name: 4th of July Fireworks Name of Applicant Organization: Bainbridge Island Lodging Association (BILA) Applicant Organization IRS Chapter Status and Tax ID Number: 501(c)3; EIN: 71-1051175 Date of Incorporation as a WA Corporation and UBI Number: January 16, 2002 / 602-175- 381 Primary Contact: Kelly Gurza and Scott Isenman Mailing Address: P.O. Box 10895, Bainbridge Island, Washington 98110 Email(s): [email protected] and [email protected] Cell phone: Kelly Gurza: 1 650 776-8306 Scott Isenman 1 206 661-6531 Project Type Tourism marketing Marketing and operations of special events and festivals designed to attract tourists. Supporting the operations of a tourism-related facility owned or operated by a nonprofit organization. Supporting the operations and/or capital expenditures of a tourism-related facility owned or operated by a municipality. LODGING/TOURISM FUND APPLICATION Applicant Information Please respond to each of these questions in the order listed. If the proposal includes multiple partners, please include the requested information for each organization. 1. Describe the applicant organization’s mission, history, and areas of expertise. Describe the applicant’s experience in tourism promotion on Bainbridge Island and its demonstrated ability to complete the proposed project. Alternate question for event or facility funding: Describe the event or facility proposed including its purpose, history, and budget. Include past attendance history, if applicable, and estimate the number of tourists drawn to the event or facility/year. Please estimate total attendance and the number of tourists estimated to attend for 2020. -

Summary of Offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019

Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 3841 Number of items in BX 301 thru BX 463 1815 Number of unique text strings used as taxa 990 Taxa offered as bulbs 1056 Taxa offered as seeds 308 Number of genera This does not include the SXs. Top 20 Most Oft Listed: BULBS Times listed SEEDS Times listed Oxalis obtusa 53 Zephyranthes primulina 20 Oxalis flava 36 Rhodophiala bifida 14 Oxalis hirta 25 Habranthus tubispathus 13 Oxalis bowiei 22 Moraea villosa 13 Ferraria crispa 20 Veltheimia bracteata 13 Oxalis sp. 20 Clivia miniata 12 Oxalis purpurea 18 Zephyranthes drummondii 12 Lachenalia mutabilis 17 Zephyranthes reginae 11 Moraea sp. 17 Amaryllis belladonna 10 Amaryllis belladonna 14 Calochortus venustus 10 Oxalis luteola 14 Zephyranthes fosteri 10 Albuca sp. 13 Calochortus luteus 9 Moraea villosa 13 Crinum bulbispermum 9 Oxalis caprina 13 Habranthus robustus 9 Oxalis imbricata 12 Haemanthus albiflos 9 Oxalis namaquana 12 Nerine bowdenii 9 Oxalis engleriana 11 Cyclamen graecum 8 Oxalis melanosticta 'Ken Aslet'11 Fritillaria affinis 8 Moraea ciliata 10 Habranthus brachyandrus 8 Oxalis commutata 10 Zephyranthes 'Pink Beauty' 8 Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 Most taxa specify to species level. 34 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for bulbs 23 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for seeds 141 taxa were listed with quoted 'Variety' Top 20 Most often listed Genera BULBS SEEDS Genus N items BXs Genus N items BXs Oxalis 450 64 Zephyranthes 202 35 Lachenalia 125 47 Calochortus 94 15 Moraea 99 31 Moraea -

Concept of an Active Amplification Mechanism in the Infrared

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 21 December 2015 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00391 Concept of an Active Amplification Mechanism in the Infrared Organ of Pyrophilous Melanophila Beetles Erik S. Schneider 1 †, Anke Schmitz 2 † and Helmut Schmitz 2*† 1 Institute of Zoology, University of Graz, Graz, Austria, 2 Institute of Zoology, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany Jewel beetles of the genus Melanophila possess a pair of metathoracic infrared (IR) organs. These organs are used for forest fire detection because Melanophila larvae can only develop in fire killed trees. Several reports in the literature and a modeling of a historic oil tank fire suggest that beetles may be able to detect large fires by means of their IR organs from distances of more than 100 km. In contrast, the highest sensitivity of the IR organs, so far determined by behavioral and physiological experiments, allows a detection of large fires from distances up to 12 km only. Sensitivity thresholds, however, have always been determined in non-flying beetles. Therefore, the complete micromechanical environment of the IR organs in flying beetles has not been taken into Edited by: Sylvia Anton, consideration. Because the so-called photomechanic sensilla housed in the IR organs Institut National de la Recherche respond bimodally to mechanical as well as to IR stimuli, it is proposed that flying Agronomique, France beetles make use of muscular energy coupled out of the flight motor to considerably Reviewed by: Maria Hellwig, increase the sensitivity of their IR sensilla during intermittent search flight sequences. University of Vienna, Austria In a search flight the beetle performs signal scanning with wing beat frequency while Daniel Robert, the inputs of the IR organs on both body sides are compared. -

The Music Center Presents Downtown LA's Largest July 4Th

Contact: Bonnie Goodman FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For Grand Park 213-308-9539 direct [email protected] The Music Center Presents Downtown LA’s Largest July 4th Celebration with Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party – Free Blockbuster Event Will Light Up the Sky from the Rooftops Surrounding Grand Park – LOS ANGELES (June 3, 2015) – Angelenos will take over the civic center as they come together for an LA-style July 4th celebration at the third annual Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party, presented by The Music Center. The free event, which runs from 3:00 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, July 4, 2015, will feature music, art, dancing, food, family, friends and fireworks for a feel-good, hometown event unlike any other Downtown LA has seen. Grand Park will light up the civic center skyline with a new, first-ever rooftop fireworks display set to iconic American music. The block party will be spread over eight city blocks, from Temple Street to 2nd Street, and from Grand Avenue to Main Street. Grand Park’s Fourth of July Block Party is supported by the County of Los Angeles, City Councilmember José Huizar, Bank of America and KCRW. During the block party, Grand Park’s green spaces will be transformed into giant picnic areas, while two dedicated stages – THE FRONT YARD on Grand Park’s Performance Lawn between Grand Avenue and Hill Street and THE BACKYARD on Grand Park’s Event Lawn between Broadway and Spring Street – will showcase a diverse lineup of LA-based musical artists, dancers, jump rope experts and spoken word artists. -

Why Mushrooms Have Evolved to Be So Promiscuous: Insights from Evolutionary and Ecological Patterns

fungal biology reviews 29 (2015) 167e178 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fbr Review Why mushrooms have evolved to be so promiscuous: Insights from evolutionary and ecological patterns Timothy Y. JAMES* Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA article info abstract Article history: Agaricomycetes, the mushrooms, are considered to have a promiscuous mating system, Received 27 May 2015 because most populations have a large number of mating types. This diversity of mating Received in revised form types ensures a high outcrossing efficiency, the probability of encountering a compatible 17 October 2015 mate when mating at random, because nearly every homokaryotic genotype is compatible Accepted 23 October 2015 with every other. Here I summarize the data from mating type surveys and genetic analysis of mating type loci and ask what evolutionary and ecological factors have promoted pro- Keywords: miscuity. Outcrossing efficiency is equally high in both bipolar and tetrapolar species Genomic conflict with a median value of 0.967 in Agaricomycetes. The sessile nature of the homokaryotic Homeodomain mycelium coupled with frequent long distance dispersal could account for selection favor- Outbreeding potential ing a high outcrossing efficiency as opportunities for choosing mates may be minimal. Pheromone receptor Consistent with a role of mating type in mediating cytoplasmic-nuclear genomic conflict, Agaricomycetes have evolved away from a haploid yeast phase towards hyphal fusions that display reciprocal nuclear migration after mating rather than cytoplasmic fusion. Importantly, the evolution of this mating behavior is precisely timed with the onset of diversification of mating type alleles at the pheromone/receptor mating type loci that are known to control reciprocal nuclear migration during mating. -

Article Extensive Trans-Specific Polymorphism at the Mating Type

Extensive Trans-Specific Polymorphism at the Mating Type Locus of the Root Decay Fungus Heterobasidion Linda T.A. van Diepen,y,z,1 A˚ke Olson,y,2 Katarina Ihrmark,2 Jan Stenlid,*,2 and Timothy Y. James*,1 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan 2Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden zPresent address: Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH yThese authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Associate editor: Naoki Takebayashi The sequence data reported in this article have been submitted in the GenBank (accession nos. KF280347–KF280390). The coding DNA sequence alignments used for this study have been deposited in the Dryad Repository under http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad. r7nt4. Abstract Downloaded from Incompatibility systems in which individuals bearing identical alleles reject each other favor the maintenance of a diversity of alleles. Mushroom mating type loci (MAT) encode for dozens or hundreds of incompatibility alleles whose loss from the population is greatly restricted through negative frequency selection, leading to a system of alleles with highly divergent sequences. Here, we use DNA sequences of homeodomain (HD) encoding genes at the locus of five MAT http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/ closely related species of the root rot basidiomycete Heterobasidion annosum sensu lato to show that the extended coalescence time of MAT alleles greatly predates speciation in the group, contrasting loci outside of MAT that show allele divergences largely consistent with the species phylogeny with those of MAT, which show rampant trans-species poly- morphism. -

Contributions to the Life-History of Tetraclinis Articu- Lata, Masters, with Some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae

Contributions to the Life-history of Tetraclinis articu- lata, Masters, with some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae. BY W. T. SAXTON, M.A., F.L.S., Professor of Botany at the Ahmedabad Institute of Science, India. With Plates XLIV-XLVI and nine Figures in the Text. INTRODUCTION. HE Gum Sandarach tree of Morocco and Algeria has been well known T to botanists from very early times. Some account of it is given by Hooker and Ball (20), who speak of the beauty and durability of the wood, and state that they consider the tree to be probably correctly identified with the Bvlov of the Odyssey (v. 60),1 and with the Ovlov and Ovia of Theo- phrastus (' Hist. PI.' v. 3, 7)/ as well as, undoubtedly, with the Citrus wood of the Romans. The largest trees met with by them, growing in an un- cultivated state, were about 30 feet high. The resin, known as sandarach, is stated to be collected by the Moors and exported to Europe, where it is used as a varnish. They quote Shaw (49 a and b) as having described and figured the tree under the name of Thuja articulata, in his ' Travels in Barbary'; this statement, however, is not accurate. In both editions of the work cited the plant is figured and described as ' Cupressus fructu quadri- valvi, foliis Equiseti instar articulatis '. Some interesting particulars of the use of the timber are given by Hansen (19), who also implies that the embryo has from three to six cotyledons. Both Hooker and Ball, and Hansen, followed by almost all others who have studied the plant, speak of it as Callitris qtiadrivalvis. -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

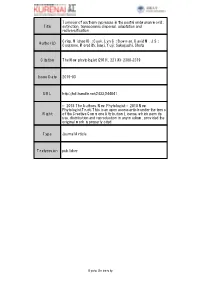

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Hill View Rare Plants, Summer Catalogue 2011, Australia

Summer 2011/12 Hill View Rare Plants Calochortus luteus Calochortus superbus Susan Jarick Calochortus albidus var. rubellus 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tas 7004 Ph 03 6224 0770 Summer 2011/12 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tasmania, 7004 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tasmania, 7004 Summer 2011/12 Hill View Rare Plants Ph 03 6224 0770 Ph 03 6224 0770 Hill View Rare Plants Marcus Harvey’s Hill View Rare Plants 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tasmania, 7004 Welcome to our 2011/2012 summer catalogue. We have never had so many problems in fitting the range of plants we have “on our books” into the available space! We always try and keep our lists “democratic” and balanced although at times our prejudices show and one or two groups rise to the top. This year we are offering an unprecedented range of calochortus in a multiplicity of sizes, colours and flower shapes from the charming fairy lanterns of C. albidus through to the spectacular, later-flowering mariposas with upward-facing bowl-shaped flowers in a rich tapestry of shades from canary-yellow through to lilac, lavender and purple. Counterpoised to these flashy dandies we are offering an assortment of choice muscari whose quiet charm, softer colours and Tulipa vvedenskyi Tecophilaea cyanocrocus Violacea persistent flowering make them no less effective in the winter and spring garden. Standouts among this group are the deliciously scented duo, M. muscarimi and M. macrocarpum and the striking and little known tassel-hyacith, M. weissii. While it has its devotees, many gardeners are unaware of the qualities of the large and diverse tribe of “onions”, known as alliums. -

ABSTRACT MITCHELL III, ROBERT DRAKE. Global Human Health

ABSTRACT MITCHELL III, ROBERT DRAKE. Global Human Health Risks for Arthropod Repellents or Insecticides and Alternative Control Strategies. (Under the direction of Dr. R. Michael Roe). Protein-coding genes and environmental chemicals. New paradigms for human health risk assessment of environmental chemicals emphasize the use of molecular methods and human-derived cell lines. In this study, we examined the effects of the insect repellent DEET (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and the phenylpyrazole insecticide fipronil (fluocyanobenpyrazole) on transcript levels in primary human hepatocytes. These chemicals were tested individually and as a mixture. RNA-Seq showed that 100 µM DEET significantly increased transcript levels for 108 genes and lowered transcript levels for 64 genes and fipronil at 10 µM increased the levels of 2,246 transcripts and decreased the levels for 1,428 transcripts. Fipronil was 21-times more effective than DEET in eliciting changes, even though the treatment concentration was 10-fold lower for fipronil versus DEET. The mixture of DEET and fipronil produced a more than additive effect (levels increased for 3,017 transcripts and decreased for 2,087 transcripts). The transcripts affected in our treatments influenced various biological pathways and processes important to normal cellular functions. Long non-protein coding RNAs and environmental chemicals. While the synthesis and use of new chemical compounds is at an all-time high, the study of their potential impact on human health is quickly falling behind. We chose to examine the effects of two common environmental chemicals, the insect repellent DEET and the insecticide fipronil, on transcript levels of long non-protein coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in primary human hepatocytes. -

Article Hygroscopicity, Kappa (Κ), Alter Atmospheric Chemistry, and Cause Short-Term Adverse from 0.11 (Background) to 0.18 (fireworks)

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 6155–6173, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-6155-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Measurement report: Firework impacts on air quality in Metro Manila, Philippines, during the 2019 New Year revelry Genevieve Rose Lorenzo1,2, Paola Angela Bañaga2,3, Maria Obiminda Cambaliza2,3, Melliza Templonuevo Cruz3,4, Mojtaba AzadiAghdam6, Avelino Arellano1, Grace Betito3, Rachel Braun6, Andrea F. Corral6, Hossein Dadashazar6, Eva-Lou Edwards6, Edwin Eloranta5, Robert Holz5, Gabrielle Leung2, Lin Ma6, Alexander B. MacDonald6, Jeffrey S. Reid7, James Bernard Simpas2,3, Connor Stahl6, Shane Marie Visaga2,3, and Armin Sorooshian1,6 1Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85721, USA 2Manila Observatory, Quezon City, 1108, Philippines 3Department of Physics, School of Science and Engineering, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, 1108, Philippines 4Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, 1101, Philippines 5Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706, USA 6Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85721, USA 7Marine Meteorology Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey, CA, USA Correspondence: Armin Sorooshian ([email protected]) Received: 2 October 2020 – Discussion started: 4 November 2020 Revised: 15 February 2021 – Accepted: 19 -

Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1557 January 2012 Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau Introduction Leyland cypress (x Cupressocyparis leylandii) is a fast- growing evergreen that has been widely planted as a landscape specimen and along boundaries to create windbreaks or privacy screening in Arizona. The presence of Seiridium canker was confirmed in Prescott, Arizona in July 2011 and it is suspected that the disease occurs in other areas of the state. Seiridium canker was first identified in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1928. Today, it can be found in Europe, Asia, New Zealand, Australia, South America and Africa on plants in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Italian cypress (C. sempervirens) are highly susceptible and can be severely impacted by this disease. Since Leyland and Italian cypress have been widely planted in Arizona, it is imperative that Seiridium canker management strategies be applied and suitable resistant tree species be recommended for planting in the future. The Pathogen Seiridium canker is known to be caused by three different fungal species: Seiridium cardinale, S. cupressi and S. unicorne. S. cardinale is the most damaging of the three species and is SCHALAU found in California. S. unicorne and S. cupressi are found in the southeastern United States where the primary host is JEFF Leyland cypress. All three species produce asexual fruiting Figure 1. Leyland cypress tree with dead branch (upper left) and main leader bodies (acervuli) in cankers. The acervuli produce spores caused by Seiridium canker. (conidia) which spread by water, human activity (pruning and transport of infected plant material), and potentially insects, birds and animals to neighboring trees where new Symptoms and Signs infections can occur.