How India's Media Landscape Changed Over Five Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai's Original Inhabitants Fear World's Tallest Statue

HEALTH FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2017 Mumbai’s original inhabitants fear world’s tallest statue MUMBAI: A fitting tribute to a local legend a gross waste of money which would be of fish to sell at markets and feed their fami- cause immense harm to a vibrant marine or a grotesque misuse of money? The deci- better spent on improving health, educa- lies. Residents say disruption caused by ecosystem. “There’s a huge diversity of fish, sion to build the world’s tallest statue just tion and infrastructure in the teeming construction will decimate their fishing fauna and invertebrates there. Fish catches, off Mumbai’s coast has divided the city. But metropolis of more than 20 million people. stocks-including pomfret, Bombay macker- sewage, and tidal currents will change,” the traditional Koli community, who el, seer fish, prawns, and crabs-while heavy wildlife biologist Anand Pendharkar said. depend on fishing for their livelihoods, fear Environmental destruction traffic ferrying tourists from three terminals “It’s going to affect the food base of the they will be worst hit by the construction, A petition on the change.org website will block access to the sea and disrupt city, it’s going to affect the economy. There warning that it threatens their centuries- opposing the bronze statue, which will wave patterns. is going to be a huge amount of damage.” old existence. India will spend 36 billion Critics question why Mumbai needs such rupees ($530 million) on the controversial a lavish statute when the city already has memorial to 17th century Hindu warrior several smaller Shivaji memorials. -

Stay Safe at Home

Stay safe at home. We have strengthened our online platforms with an aim to serve your needs uniterruptedly. Access our websites: www.nipponindiamf.com www.nipponindiapms.com (Chat feature available) www.nipponindiaetf.com www.nipponindiaaif.com Click to download our mobile apps: Nippon India Mutual Fund | Simply Save App For any further queries, contact us at [email protected] Mutual Fund investments are subject to market risks, read all scheme related documents carefully. INDIA-CHINA: TENSION PEAKS IN LADAKH DIGITAL ISSUE www.outlookindia.com June 8, 2020 What After Home? Lakhs of migrants have returned to their villages. OUTLOOK tracks them to find out what lies ahead. Mohammad Saiyub’s friend Amrit Kumar died on their long journey home. Right, Saiyub in his village Devari in UP. RNI NO. 7044/1961 MANAGING EDITOR, OUTLOOK FROM THE EDITOR Returning to RUBEN BANERJEE the Returnees EDITOR IN CHIEF and apathy have been their constant companions since then. As entire families—the old, infirm and the ailing included—attempt to plod back home, they have been sub- NDIA is working from home; jected to ill-treatment and untold indignities by the police Bharat is walking home—the short for violating the lockdown. Humiliation after humiliation tweet by a friend summing up was heaped upon them endlessly as they walked, cycled and what we, as a locked-down nation, hitchhiked long distances. They were sprayed with disin- have been witnessing over the past fectants and fleeced by greedy transporters for painful two months was definitely smart. rides on the back of trucks and tempos. -

The-Hindu-Special-Diary-Complete

THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 2 DIARY OF EVENTS 2015 THE HINDU THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 panel headed by former CJI R. M. Feb. 10: The Aam Aadmi Party NATIONAL Lodha to decide penalty. sweeps to power with 67 seats in the Indian-American author Jhumpa 70-member Delhi Assembly. JANUARY Lahiri wins the $ 50,000 DSC prize Facebook launches Internet.org for Literature for her book, The in India at a function in Mumbai. Jan. 1: The Modi government sets Lowland . ICICI Bank launches the first dig- up NITI Aayog (National Institution Prime Minister Narendra Modi ital bank in the country, ‘Pockets’, on for Transforming India) in place of launches the Beti Bachao, Beti Pad- a mobile phone in Mumbai. the Planning Commission. hao (save daughters, educate daugh- Feb. 13: Srirangam witnesses The Karnataka High Court sets up ters) scheme in Panipat, Haryana. over 80 per cent turnout in bypolls. a Special Bench under Justice C.R. “Sukanya Samrudhi” account Sensex gains 289.83 points to re- Kumaraswamy to hear appeals filed scheme unveiled. claim 29000-mark on stellar SBI by AIADMK general secretary Jaya- Sensex closes at a record high of earnings. lalithaa in the disproportionate as- 29006.02 Feb. 14: Arvind Kejriwal takes sets case. Jan. 24: Poet Arundhati Subra- oath as Delhi’s eighth Chief Minis- The Tamil Nadu Governor K. Ro- manian wins the inaugural Khush- ter, at the Ramlila Maidan in New saiah confers the Sangita Kalanidhi want Singh Memorial Prize for Delhi. award on musician T.V. Gopalak- Poetry for her work When God is a Feb. -

Times City the Times of India, Mumbai | Wednesday, February 18, 2015

TIMES CITY THE TIMES OF INDIA, MUMBAI | WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2015 HOW TO DOWNLOAD Get the free Alive App: STEP 2 Picture Scan: Open the Alive app on your phone and scan the STEP 3 Watch the Available on select android (version 4.0 and AND USE ALIVE APP Give a missed call to picture by focusing your phone’s camera on it. QR Code Scan: Open the photo come Alive. above), iOS (version 7.0 and above), BB 18001023324 or visit Alive app and tap on the ‘QR code’ tab at the bottom of the screen. Fill the View it and share (version 5.0 and above), Symbian (version S60 PAGES16 alivear.com from your mobile phone QR code inside the square and hold still. Available on iOS and Android only. it with friends. and above), Windows (version 7.5 and above) 400 bars, pubs & restaurants could get to stay open 24x7 had assured them he would involve revenue and jobs, but without incon- State Set To Amend Laws In Monsoon Session; Hoteliers’ Body all stakeholders before deciding the veniencing residents. “The legisla- line of amendments in laws such as tion can allow those places which Meets Netas, Tells Them Move Will Bring In Revenue, Tourists the Shops and Establishments Act. have an inbuilt mechanism to take HRAWI office-bearers Gogi Singh, care of security, traffic, etc. in com- Chittaranjan.Tembhekar night entertainment zones for ment. The police have said they have Dilip Datwani and Pradip Shetty mercial areas to serve through the @timesgroup.com Mumbaikars as well as tourists. -

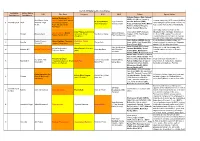

LIST of MEDIA RIGHTS VIOLATIONS by JOURNALIST SAFETY INDICATES (JSIS), MAY 2018 to APRIL 2019 the Media Violations Are Categorised by the Journalist Safety Indicators

74 IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2018–2019 LIST OF MEDIA RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY JOURNALIST SAFETY INDICATES (JSIS), MAY 2018 TO APRIL 2019 The media violations are categorised by the Journalist Safety Indicators. Other notable incidents are media violations recorded by the IFJ in its violation mapping. *Other notable incidents are media violations recorded by the IFJ. These are violations that fall outside the JSIs and are included in IFJ mapping on the South Asia Media Solidarity Network (SAMSN) Hub - samsn.ifj.org Afghanistan, was killed in an attack on the Sayeed Ali ina Zafari, political programs operator police chief of Kandahar, General Abdul Raziq. on Wolesi Jerga TV; and a Wolesi Jerga TV driver AFGHANISTAN The Taliban-claimed attack took place in the were entering the MOFA road for an interview in governor’s compound during a high-level official Zanbaq square when they were confronted by a JOURNALIST KILLINGS: 12 (Journalists: 5, meeting. Angar, along with others, was killed in policeman. Media staff: 7. Male: 12, Female: 0) the cross-fire. THREATS AGAINST THE LIVES OF June 5, 2018: Takhar JOURNALISTS: 8 December 4, 2018: Nangarhar Milli TV Takhar province reporter Merajuddin OTHER THREATS TO JOURNALISTS: Engineer Zalmay, director and owner or Enikass Sharifi was beaten up by the head of the None recorded radio and TV stations was kidnapped at 5pm community after a verbal disagreement. NON-FATAL ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS: during a shopping trip. He was taken by armed 61 (Journalists: 52; Media staff: 9) men who arrived in an armoured vehicle. His June 11, 2018, Ghor THREATS AGAINST MEDIA INSTITUTIONS: 3 driver was shot and taken to hospital where he Saam Weekly Director, Nadeem Ghori, had his ATTACKS ON MEDIA INSTITUTIONS: 3 later died. -

Page7national.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU FRIDAY, AUGUST 7, 2020 (PAGE 7) Why is PM lying : Rahul Leaders remember Sushma Swaraj Temple of presiding deity of Lord Ram’s NEW DELHI, Aug 6: clan hopes for huge footfalls Continuing his attack on Prime Minister Narendra Modi on on her first death anniversary AYODHYA, Aug 6: It is believed that after the "Once the Ram Temple is the India-China border standoff, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi on birth of Lord Ram, his mother built, devotees will flock NEW DELHI, Aug 6: me as my strength. Krishna look to #SushmaSwaraj Ji on her 1st Thursday pointed to a new Defence Ministry document on Tucked away in one of the Kaushalya visited the temple Ayodhya to have a glimpse of after my mother!," Swaraj's death anniversary. Will always Chinese transgression in the areas of Kugrang Nala and north bank numerous bylanes of Ayodhya with her entire family. Lord Ram, as well as Badhi Rich tributes poured in on daughter Bansuri said on remember her as a great orator, of Pangong Tso in May 17-18 and asked why the PM was lying on around two km from the site for "Since then, whenever a Devkaali temple. I am confident Thursday for former External Twitter. visionary leader and above all a the matter. the Ram Mandir is the temple of child is born in any home, the that people become aware of Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj In her tenure as external compassionate human being," In a post on the social media, Mr Badhi Devkaali-the 'kuldevi' or this temple's impor- on her first death anniversary, Prasad tweeted. -

Hizb Ambush in J&K Leaves Three Soldiers, Civilian Dead

follow us: friday, february 24, 2017 Delhi City Edition thehindu.com 36 pages ț ₹10.00 facebook.com/thehindu twitter.com/the_hindu SC agrees to hear Over 61% polling in Bharti Airtel to buy Indian bowlers Nambi Narayanan’s phase 4 of Uttar Telenor's India unit keep Australia on petition in April Pradesh elections in no-cash deal a tight leash page 7 page 11 page 13 Page 15 Printed at . Chennai . Coimbatore . Bengaluru . Hyderabad . Madurai . Noida . Visakhapatnam . Thiruvananthapuram . Kochi . Vijayawada . Mangaluru . Tiruchirapalli . Kolkata . Hubballi . Mohali . Allahabad . Malappuram . Mumbai NEARBY Hizb ambush in J&K leaves BJP sweeps Maharashtra, three soldiers, civilian dead trails Sena in Mumbai Boost for Fadnavis as party wins 8 out of 10 municipalities Abhay Chautala arrested for violating orders Lt. Colonel, Major among 5 injured as militants attack Army convoy in Shopian Alok Deshpande CHANDIGARH Mumbai Punjab police on Thursday Peerzada Ashiq The Bharatiya Janata Party arrested Indian National Srinagar (BJP) continued its political Lok Dal (INLD) leaders Three soldiers were killed dominance in Maharashtra including Leader of and five others, including a with resounding electoral opposition in Haryana Lieutenant Colonel and a victories in key municipalit- Assembly Abhay Chautala Major, were injured when ies and zilla parishads across for violating prohibitory militants ambushed an Army the State. It won eight of the orders. convoy in Shopian early on 10 municipal elections that NORTH Ī PAGE 2 Thursday. One woman was were held on February 21. Modi lights into Akhilesh also killed in the crossfire. The Shiv Sena, its erstwhile for ‘donkey’ barb A Srinagar-based police ally, won in Mumbai and Bahraich (U.P.) spokesman told The Hindu Thane. -

Zakir Naik: What Did I Do to Earn the Tags of ‘Dr Terror’, ‘Hate Monger’? Islamic Scholar Dr

www.Asia Times.US NRI Global Edition Email: [email protected] September 2016 Vol 7, Issue 9 Zakir Naik: What did I do to earn the tags of ‘Dr Terror’, ‘Hate Monger’? Islamic scholar Dr. Zakir Naik wrote an open letter to Indians called ‘Five Questions and an Appeal’ where he lamented about being targeted and labeled a ‘terror preacher’ in India. In the letter, Naik said, “Of 150 countries where I’m respected and my talks are welcomed, I’m being called a terrorist influencer in my own country. What an irony. Why now, when I’ve been doing the same thing for over 25 years?”. Naik, 51, is an Islamic preacher, who founded the Islamic Research Foundation in 1991 when he started Dawah or religious preaching. His lectures mostly revolve around how Islam is superior to all other faiths. While he claims to be an advocate of interfaith dialogue, his preaching’s’ reinforce all the stereotypes which exist against Muslims. Following reports that one of the militants of Dhaka terror attack was inspired by Naik’s misinterpretations of Islam, there are growing demand for strict action against him. In the letter, Naik asks why he has become the enemy number one for the State and Central government. “It has been over two months since the ghastly terror attack in Dhaka, and over one month since I’ve been asking myself what exactly have I done to become the enemy number one of the media as well as the State and Central Gov- ernment,” wrote Naik. × and justice. He also questioned the repeated investigations on him by government agencies. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government. -

Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Candidate List.Xlsx

List of All Maharashtra Candidates Lok Sabha Vidhan Sabha BJP Shiv Sena Congress NCP MNS Others Special Notes Constituency Constituency Vishram Padam, (Raju Jaiswal) Aaditya Thackeray (Sunil (BSP), Adv. Mitesh Varshney, Sunil Rane, Smita Shinde, Sachin Ahir, Ashish Coastal road (kolis), BDD chawls (MHADA Dr. Suresh Mane Vijay Kudtarkar, Gautam Gaikwad (VBA), 1 Mumbai South Worli Ambekar, Arjun Chemburkar, Kishori rules changed to allow forced eviction), No (Kiran Pawaskar) Sanjay Jamdar Prateep Hawaldar (PJP), Milind Meghe Pednekar, Snehalata ICU nearby, Markets for selling products. Kamble (National Peoples Ambekar) Party), Santosh Bansode Sewri Jetty construction as it is in a Uday Phanasekar (Manoj Vijay Jadhav (BSP), Narayan dicapitated state, Shortage of doctors at Ajay Choudhary (Dagdu Santosh Nalaode, 2 Shivadi Shalaka Salvi Jamsutkar, Smita Nandkumar Katkar Ghagare (CPI), Chandrakant the Sewri GTB hospital, Protection of Sakpal, Sachin Ahir) Bala Nandgaonkar Choudhari) Desai (CPI) coastal habitat and flamingo's in the area, Mumbai Trans Harbor Link construction. Waris Pathan (AIMIM), Geeta Illegal buildings, building collapses in Madhu Chavan, Yamini Jadhav (Yashwant Madhukar Chavan 3 Byculla Sanjay Naik Gawli (ABS), Rais Shaikh (SP), chawls, protests by residents of Nagpada Shaina NC Jadhav, Sachin Ahir) (Anna) Pravin Pawar (BSP) against BMC building demolitions Abhat Kathale (NYP), Arjun Adv. Archit Jaykar, Swing vote, residents unhappy with Arvind Dudhwadkar, Heera Devasi (Susieben Jadhav (BHAMPA), Vishal 4 Malabar Hill Mangal -

Front Matter

This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Feminist technosciences Rebecca Herzig and Banu Subramaniam, Series Editors This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms HOLY SCIENCE THE BIOPOLITICS OF HINDU NATIONALISM Banu suBramaniam university oF Washington Press Seattle This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Financial support for the publication of Holy Science was provided by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Engagement, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Copyright © 2019 by the University of Washington Press Printed and bound in the United States of America Interior design by Katrina Noble Composed in Iowan Old Style, typeface designed by John Downer 23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. university oF Washington Press www.washington.edu/uwpress LiBrary oF congress cataLoging-in-Publication Data Names: Subramaniam, Banu, 1966- author. Title: Holy science : the biopolitics of Hindu nationalism / Banu Subramaniam. -

Download the Government, Politics and Regulation Section of The

M A R C H 2 0 1 9 Media Influence Matrix: India Government, Politics and Regulation Authors: Vibodh Parthasarathi, Simran Agarwal Researcher: Manisha Venkat Editor: Marius Dragomir Published by CEU Center for Media, Data and Society (CMDS), Budapest, 2019 About CMDS About the authors The Center for Media, Data and Society Vibodh Parthasarathi maintains a multidisciplinary (CMDS) is a research center for the interest in media policy and creative industries. On study of media, communication, and extraordinary leave during 2017-19 from his information policy and its impact on tenure at Jamia Millia Islamia, he has been society and practice. Founded in 2004 awarded visiting positions at the University of as the Center for Media and Queensland and at KU Leuven, besides at CPS, Indian Communication Studies, CMDS is part Institute of Technology Bombay. His latest work is the of CEU’s School of Public Policy and co-edited double volume The Indian Media serves as a focal point for an Economy (OUP 2018). international network of acclaimed scholars, research institutions and Simran Agarwal is a media research scholar and a activists. project associate at the Centre for Policy Studies, IITB. She holds a Master’s degree in Media Governance from Jamia Millia Islamia where she developed a keen interest in the political economy of the media and in narrowing CMDS ADVISORY BOARD the wide disconnect between media policy priorities and society. She was previously in the team producing the Clara-Luz Álvarez annual Free Speech Report by The Hoot. Floriana Fossato Ellen Hume Manisha Venkat is an undergraduate in media studies Monroe Price from the College of Media at the University of Illinois Anya Schiffrin where she primarily focused on advertising and creative Stefaan G.