The Origin of the Byzantine Text New Perspectives in a Deadlocked Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solid Rock Greek New Testament : Theory and Practice

The Solid Rock Greek New Testament: Theory and Practice Joey McCollum Abstract The Solid Rock Greek New Testament: Scholar’s Edition offers a recon- structed text of the New Testament based on Byzantine priority theory and expands upon the work of the SBL Greek New Testament by compar- ing the readings of over 10 major critical editions at nearly 8000 units of textual variation. In this survey, we will discuss the goals, principles, and processes underlying the development of this edition, focusing especially on the design and use of the apparatus. As we will show, the resources available in this work make it a valuable addition to the library of anyone involved in the teaching, translation, or study of the Greek New Testament. 1 Introduction 1.1 New Testament Textual Criticism For nearly as long as the Church has recognized the scriptures of the New Testament (ΝΤ) as authoritative, it has also understood that not all copies of these scriptures agree with one another.¹ If we assume that each book of the NT originated in a single inspired autograph, then any two manuscripts cannot both be right where they disagree.² More to the point, where any difference 1. The early church fathers occasionally took note of such differences in the manuscripts known to them. For this reason, their notes serve as crucial evidence for variant readings, sometimes in cases when the reading in the patristic citation has not survived in any NT manuscript. A comprehensive study can be found in Amy M. Donaldson, “Explicit References to New Testament Variant Readings among Greek and Latin Church Fathers” (PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2009). -

3 the Westcott-Hort Critical Theory

3 THE WESTCOTT-HORT CRITICAL THEORY Although Brooke Foss Westcott identified himself fully with the project and the results, it is generally understood that it was mainly Fenton John Anthony Hort 1 who developed the theory and composed the Introduction in their two-volume work. 2 In the following discussion I consider the W-H theory to be Hort's creation. At the age of 23, in late 1851, Hort wrote to a friend: “I had no idea till the last few weeks of the importance of texts, having read so little Greek Testament, and dragged on with the villainous Textus Receptus . Think of that vile Textus Receptus leaning entirely on late MSS.; it is a blessing there are such early ones.” 3 Scarcely more than a year later, "the plan of a joint [with B.F. Westcott] revision of the text of the Greek Testament was first definitely agreed upon".4 And within that year (1853) Hort wrote to a friend that he hoped to have the new text out "in little more than a year".5 That it actually took twenty-eight years does not obscure the circumstance that though uninformed, by his own admission, Hort conceived a personal animosity for the Textus Receptus ,6 and only because it was based entirely, so he thought, on late manuscripts. It appears that Hort did not arrive at his theory through unprejudiced intercourse with the facts. Rather, he deliberately set out to construct a theory that would vindicate his preconceived animosity for the Received Text. Colwell has made the same observation: "Hort organized his entire argument to depose the Textus Receptus".7 And again, “Westcott and Hort wrote with two things constantly in mind; the Textus Receptus and the Codex Vaticanus. -

The Contributions of Textual Criticism to the Interpretation of the New Testament

Restoration Quarterly Volume 5 | Number 4 Article 2 10-1-1961 The onC tributions of Textual Criticism to the Interpretation of the New Testament Frank Pack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pack, Frank (1961) "The onC tributions of Textual Criticism to the Interpretation of the New Testament," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 5 : No. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol5/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. RESTORATION QUARTERLY CONTENTS An Introduction : Th e Task and Method of Ex egesis -Abraham J . Malh erbe ...................................................... .......... 169 Th e Contributions of Textu al Criticism t o th e Inte rpret ation of th e New Testa ment-F ran k Pack ......................................... 179 Th e Lan guage Backgro und of the New Testam ent-J . W. Rober ts 193 Th e Psych ological App roac h to Int er pret ation-Paul Sou thern .... 205 Th e J ewish Background of the New Testament-J ack P. La wis .. 209 Th e Pagan Back gro und of th e New Testam ent - Roy Bowen Wa r d ........................................................................ 216 Patri stic Int er pretat ion of th e Bible-William M. -

Reflections on Moravian Pietism

REFLECTIONS ON MORAVIAN PIETISM By ELIZABETH ZORB* NOT everyone who has been crucified, burned at the stake, or thrown to the lions has left his mark on history. But John Hus did. John Hus was burned at the stake in Constance in July, 1415, and his martyr's death had far reaching consequences-as far reaching as Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Salem, North Carolina- cities on a continent of which Hus had never even heard. His death rekindled a Bohemian national religious revolt that led, some forty years later, to the founding of a pre-Reformation church, the Unitas Fratrum. Members of the Unitas Fratrum, also known as the Bohemian Brethren, were protestant pietists, long before either of these words was generally used or had acquired its present meaning. By 1550 there were three branches of the Unitas Fratrum: in Bohemia, in Moravia, and in Poland, with a membership of about 200,000. About a century and a half after its founding, the Unitas Fratrum had a great leader and bishop, John Amos Comenius (1592-1670), who is best known as a pioneer of modern educa- tional theories, a man of universal learning, author of some two hundred treatises on an immense variety of subjects-scientific, philosophical, literary, and linguistic, as well as theological. He transmitted a reverence for learning and a high standard of educa- tion to the succeeding generations of his Moravian Brethren. Co- menius is known to many as the father of the elementary school, of the grade-school method, and of visual education. He apparently issued one of the first picture books ever written for children and his book The School of Infancy was particularly famous. -

Kurt Aland in Memoriam

KURT ALAND IN MEMORIAM KURT ALAND IN MEMORIAM 0 1995 by Hemiann KurstStifhlng zur POdenmg der neuteslameniüchenTextfnaehmg M143Münrier/W., Geo~gskornmende7 HersieUunp: Re-g Münster INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Universitätsprediger Prof. Dr. Friedemann Merke1 Predigt im Trauergottesdienst für Prof. D. Kurt Aland am 21. April 1994 .......................................................................................... 7 Grußworte und Reden anläßlich der Gedenkakademie für Prof. D. Kurt Aland am 31. März 1995 im Festsaal des Rathauses zu Münster: Präses D. Hans-Martin Linnemann, stellv. Vorsitzender des Kuratoriums der Hermann Kunst-Stiftung zur Förderung der neutestamentlichen Textforschung Grußwort................................................................................................. 12 Prof. Dr. Erdmann Sturm, Dekan der Evangelisch-Theologi- schen Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster Grußwort.............................................................................................. 14 Prof. Dr. Martin Hengel Laudatio Kurt Aland ............................................................................. 17 Landesbischof i.R. Prof. D. Eduard Lohse, Vorsitzender des Vorstands der Hermann Kunst-Stiftung zur Förderung der neutestamentlichen Textforschung Wahrheit des Evangeliums - Zum Gedenken an Kurt Aland .... 35 Bibliographie Kurt Aland (zusammengestellt von Beate Köster und Christian Uhlig t)..... 41 Die wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiter Kurt Alands seit 1959............ 72 Friedemann Merke1 PREDIGT IM TRAUERGOTTESDIENST'FÜR -

Westcott and Hort

The Bible’s First Question “YEA, HATH GOD SAID?” (Satan’s question) Genesis 3:1 1 The Bible’s 2nd Question “WHERE ART THOU?” (God’s question) Genesis 3:9 2 Psalm 11:3—Key Verse “If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?” (Psalm 11:3) The FOUNDATION of ALL DOCTRINE is the BIBLE. Having the RIGHT BIBLE is critically IMPORTANT!! 3 600 Years of English Bible Versions Years Bibles & N.T’s Years Between Undated 1+6 = 7 --------- 1300's 3+1 = 4 25 years 1400's 0+0 = 0 100 years 1500's 11+20 = 31 3.2 years 1600's 5+3 = 8 12.5 years 1700's 17+29 = 46 2.1 years 1800's 45+90 = 135 .74 years 1900's 53+144 = 197 .51 years __________________________________________________ 1300's--1900's 135+293 = 428 1.4 years 4 CHAPTER I God’s Words Kept Intact Is BIBLE PRESERVATION (The Bible’s Timelessness) 5 Verses on Bible Preservation 1. Psalm 12:6-7: “The WORDS of the LORD are pure WORDS: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt KEEP THEM, O LORD, Thou shalt PRESERVE them from this generation FOR EVER.” 2. Psalm 105:8: “He hath remembered His covenant FOR EVER, the WORD which He commanded TO A THOUSAND GENERA- TIONS.” 6 Verses on Bible Preservation 3. Proverbs 22:20-21. “(20) Have not I WRITTEN to thee excellent things in counsels and knowledge, (21) That I might make thee know the CERTAINTY of the WORDS OF TRUTH; that thou mightest answer the WORDS OF TRUTH to them that send unto thee?” 4. -

Is James White Right About Westcott and Hort and the Modern "Vatican Versions"?

Is James White right about Westcott and Hort and the modern "Vatican Versions"? Are the modern versions like the ESV, NIV, NASB, NET, Holman Standard etc. still based on the Westcott and Hort Revised Greek critical Text? The short answer is an absolute and unequivocal Yes, they are. Some proponents of today’s new Vatican Versions like James White try to distance themselves from Westcott and Hort because so much information has come out documenting the beliefs and apostasy of these two men who are primarily responsible for the critical Greek text that underlies such modern versions as the ESV, NIV, NASB. In his book, the King James Only Controversy, James White makes some interesting and contradictory statements regarding Westcott and Hort. On page 33 Mr. White writes: “Westcott and Hort used Sinaiticus and Vaticanus to produce their New Testament, a work that displaced the text used by the KJV, later known as the Textus Receptus, in scholarly studies.” Note: Sinaiticus and Vaticanus are the so called “oldest and best manuscripts” by those who promote the UBS, Nestle-Aland Critical Greek text that underlies the N.T. of such modern versions as the ESV, NIV, NASB and the modern Catholic versions like the St. Joseph NAB 1970 and the New Jerusalem bible 1985 as well. Then on page 99 Mr. White writes: “KJV Only advocates love to hate B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort. Westcott and Hort’s work on the Greek New Testament is seen as a focal point of the attempt to “dethrone” the KJV and its underlying Greek text, the Textus Receptus. -

2Pe 1:20-21 Knowing This First, That No Prophecy of the Scripture Is of Any Private Interpretation

KJV – KING JAMES VERSION BIBLE – STUDY: LESSON 2. WHY THE KING JAMES BIBLE : LESSON TWO. We continue in our study of why the KJV is the only accurate, reliable and true Word of God for English speaking people. Please understand this is a vast subject and this bible study will only cover the basic information to assist you to know the difference between the true Word of God and corrupt versions of the Bible. In the previous lesson we learnt that Satan attacks the Word of God by changing it and corrupting it, by adding words, subtracting words, questioning it, watering down, and outright denial of doctrines taught. Quote by Pastor Richard Jordan (MSS 103/Pg 2) “I’ve said to you over and over that God’s Word can’t be erased from the face of the earth so Satan’s intent is to try to corrupt it, to put things in it that cause you not to believe that the whole thing is inspired so that when you look at a verse you say, “Well, is it or isn’t it?” and there’s a question in your mind. You have to decide for yourself whether it is or it isn’t. When you give a subjective opinion, you set up a competing authority, and a third authority has to decide. So who’s going to be the third authority? Well, you’re going to be. It will be you or your school or Doctor So-and-so or some scholars or anybody but that Book.” God promised to PRESERVE His Word. -

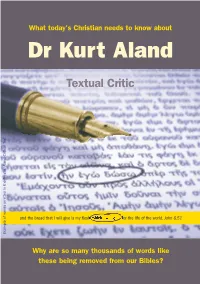

The Doctrinal Views of Dr Kurt Aland, Textual Critic

A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 1 What today's Christian needs to know about Dr Kurt Aland Textual Critic and the bread that I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world. John 6.51 Example of words omitted in the Nestle/Aland Critical Text Why are so many thousands of words like these being removed from our Bibles? A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 3 What today's Christian needs to know about DR KURT ALAND Textual Critic A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 4 Product Code: A122 ISBN 978 1 86228 344 2 © 2007 Trinitarian Bible Society Tyndale House, Dorset Road, London, SW19 3NN, UK 5M/12/07 A122 e:A122 Kurt Aland 22/11/2007 13:03 Page 1 What today's Christian needs to know about DR KURT ALAND Textual Critic by A. Hembd, MACS Reformation International Theological Seminary A consultant to the Society r Kurt Aland is perhaps the Received Text which was used by all most renowned Biblical the great translations of the textual critic of the Reformation, including the Authorised 20th century. Born in Version in the English language (also DBerlin in 1915, he died in Münster/ known in some parts of the world as Westphalia in 1994. The most famous the ‘King James Version’). Thus, the modern English versions of the New versions translated from this new Testament—the Revised Standard ‘critical’ text differ significantly from Version, the New American Standard our Authorised Version as well. -

Which Greek Text 1

Part 1 1.1 The scope of our brief study is? -The Scope of our teaching on 'Which Greek Text?' -Time will allow us to only focus on the Greek Text of the New Testament. -We will focus on the various English translations only to differentiate which of 2 Greek texts they are translated from -The Old Testament is based on the Masoretic text and is less controversial than the two main texts of the NT -By God’s grace and providence there are not as many variant readings among the Hebrew Old Testament manuscripts as there are among the Greek New Testament manuscripts. -Most of the variants concern pronunciations which do not affect translation. -The Masoretes were rabbis who made it their special work to correct the faults that had crept into the text of the Old Testament during the Babylonian captivity, and to prevent, for the future, its being corrupted by any alteration. -Aligns very well with the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Greek OT, the LXX -We will focus on the NT Greek Texts, we will lightly touch upon the English Translations only as they relate to the Greek text from which they were translated. 1.2 What would be your ideal language and your ideal New Testament? I would be fluent in speaking, writing, understanding Koine Greek, the language of the NT. My New Testament would be copied directly from the Original Autographs That would be ideal. Unfortunately we have to translate the Greek into English. And we do not have original autographs! -Koine is the Greek word for "common." Koine Greek (also called ‘New Testament Greek’) was the form of the Greek language used from around 300 BC to AD 300. -

The Text of the New Testamentl

Grace Theological lournal9.2 (1988) 279- 285 REVIEW ARTICLE The Text of the New Testament l DANIEL B. WALLACE The Text of the New Testament, by Kurt and Barbara Aland. Translated by Erroll F. Rhodes. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans/Leiden: E. 1. Brill, 1987. Pp. xviii + 338. $29.95. Cloth. With the long-awaited translation of Der Text des Neuen Testaments (1982), English-speaking students may now share in the debt of gratitude owed to the well-known German scholars, Kurt and Barbara Aland. The five-year delay, due to a number of complications, has resulted in more than a translation; the English edition "represents a revision of the original Ger man edition of 1982" (translator's preface, viii). Though modeled after Wtirthwein's Der Text des Alten Testaments (ET: The Text of the Old Testament [1979]), the NT counterpart tends to be more practical since a follow-up volume by Kurt Aland for advanced students is in the present time (Uberliejerung und Text des Neuen Testaments: Handbuch der modernen Textkritik). Nevertheless, the advanced student and scholar alike can profit from this volume: the computer-generated/ assisted tables, charts, and collations are, by themselves, worth the price of the book, representing the equivalent of countless thousands of man-hours. This could only have been produced at the Institute for New Testament Textual Re search in Munster. Besides sixty-five plates (all but three of various NT manuscripts), eight tables and six charts (including one two-sided detached fold-out), the Alands have provided the essentials for a thorough introduction to textual criticism: an overview of the history of the printed NT text-from Erasmus to Nestle Aland26 (=UBSGNT3); a discussion of the interrelation of early church history and NT textual criticism (our appetites are barely whet, however, in the twenty-four pages on this topic); a description of the extant Greek manuscripts, as well as Greek patristic evidence (it should be noted here that readers of Metzger's Text of the New Testament2 will find this chapter to be II wish to thank Dr. -

BOOK REVIEWS KURT ALAND Und BARBARA ALAND, Der Text Des

BOOK REVIEWS KURTALAND und BARBARAALAND, Der Text des Neuen Testaments.Einfiihrung in die wissenschaftlichenAusgaben und in Theoriewie Praxis der modernenTextkritik, Zweite, ergänzte und erweiterte Auflage (Stuttgart. Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1989) 374 pp. KURTALAND and BARBARAALAND, The Text of the New Testament:An Introduc- tion to the CriticalEditions and to the Theoryand Practiceof ModernTextual Criticism. Translated by Erroll F. Rhodes. Second Edition, Revised and Enlarged (Grand Rapids. William B. Eerdmans, and Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989) xviii + 366 pp. Textual criticism is not as static a subject as some mistakenly think. The com- prehensive and detailed introduction to the discipline by Kurt and Barbara Aland published in 1982 has now been expanded and revised. In the seven years between the first and second German editions several significant developments have occur- red and are represented here. The first English edition appeared in 1987 and thus was able to incorporate some of these changes. The English translation of the second edition (ET2) is in parallel with the Ger- man (G 2). This was not the case with ET As a publication ET 2 has certain advantages over G 2. The German publishers were reluctant to reset large numbers of pages, hence extensive additional material has had to be relegated to an appen- dix : ET 2 has assimilated all these additions ad loc, which makes it easier to consult. It is particularly helpful to have both lists and both tables of Byzantine manu- scripts in one place as in ET 2. The charts of the textual character and contents of New Testament papyri and uncials are printed as an end-paper in ET, the Ger- man equivalents are virtually indecipherable especially now that many more manuscripts have been added in G has abandoned the use of graph paper for these charts but this has not increased legibility).