The Generation of Plate Tectonics from Mantle Convection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sediment Diagenesis

Sediment Diagenesis http://eps.mcgill.ca/~courses/c542/ SSdiedimen t Diagenes is Diagenesis refers to the sum of all the processes that bring about changes (e.g ., composition and texture) in a sediment or sedimentary rock subsequent to deposition in water. The processes may be physical, chemical, and/or biological in nature and may occur at any time subsequent to the arrival of a particle at the sediment‐water interface. The range of physical and chemical conditions included in diagenesis is 0 to 200oC, 1 to 2000 bars and water salinities from fresh water to concentrated brines. In fact, the range of diagenetic environments is potentially large and diagenesis can occur in any depositional or post‐depositional setting in which a sediment or rock may be placed by sedimentary or tectonic processes. This includes deep burial processes but excldludes more extensive hig h temperature or pressure metamorphic processes. Early diagenesis refers to changes occurring during burial up to a few hundred meters where elevated temperatures are not encountered (< 140oC) and where uplift above sea level does not occur, so that pore spaces of the sediment are continually filled with water. EElarly Diagenesi s 1. Physical effects: compaction. 2. Biological/physical/chemical influence of burrowing organisms: bioturbation and bioirrigation. 3. Formation of new minerals and modification of pre‐existing minerals. 4. Complete or partial dissolution of minerals. 5. Post‐depositional mobilization and migration of elements. 6. BtilBacterial ddtidegradation of organic matter. Physical effects and compaction (resulting from burial and overburden in the sediment column, most significant in fine-grained sediments – shale) Porosity = φ = volume of pore water/volume of total sediment EElarly Diagenesi s 1. -

Archimedean Proof of the Physical Impossibility of Earth Mantle Convection by J. Marvin Herndon Transdyne Corporation San Diego

Archimedean Proof of the Physical Impossibility of Earth Mantle Convection by J. Marvin Herndon Transdyne Corporation San Diego, CA 92131 USA [email protected] Abstract: Eight decades ago, Arthur Holmes introduced the idea of mantle convection as a mechanism for continental drift. Five decades ago, continental drift was modified to become plate tectonics theory, which included mantle convection as an absolutely critical component. Using the submarine design and operation concept of “neutral buoyancy”, which follows from Archimedes’ discoveries, the concept of mantle convection is proven to be incorrect, concomitantly refuting plate tectonics, refuting all mantle convection models, and refuting all models that depend upon mantle convection. 1 Introduction Discovering the true nature of continental displacement, its underlying mechanism, and its energy source are among the most fundamental geo-science challenges. The seeming continuity of geological structures and fossil life-forms on either side of the Atlantic Ocean and the apparent “fit’ of their opposing coastlines led Antonio Snider-Pellegrini to propose in 1858, as shown in Fig. 1, that the Americas were at one time connected to Europe and Africa and subsequently separated, opening the Atlantic Ocean (Snider-Pellegrini, 1858). Fig. 1 The opening of the Atlantic Ocean, reproduced from (Snider-Pellegrini, 1858). 1 Half a century later, Alfred Wegener promulgated a similar concept, with more detailed justification, that became known as “continental drift” (Wegener, 1912). Another half century later, continental drift theory was modified to become plate tectonics theory (Dietz, 1961;Hess, 1962;Le Pichon, 1968;Vine and Matthews, 1963). Any theory of continental displacement requires a physically realistic mechanism and an adequate energy source. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

(2 Points Each) 1. the Velocity Of

GG 101, Spring 2006 Name_________________________ Exam 2, March 9, 2006 A. Fill in the blank (2 points each) 1. The velocity of an S-wave is ______lower_________ than the velocity of a P-wave. 2. What type of seismic wave is being recorded by the above diagram? A __P__ wave. 3. The most voluminous layer of Earth is the ___mantle_________. 4. The rigid layer of Earth which consists of the crust and uppermost mantle is called the __ lithosphere__________. 5. Which of the major subdivisions of Earth's interior is thought to be liquid? ____outer core________. 6. When the giant ice sheets in the northern hemisphere melted after the last ice age, the Earth's crust ____rebounded____ because a large weight was removed. Name _______________________________ GG 101 Exam 2 Page 2 7. The process described in question 6 is an example of ___isostasy____. 8. Earth's dense core is thought to consist predominantly of ____iron________. 9. The island of Hawaii experiences volcanism because it is located above a(n) ___hot spot_________. 10. The Himalaya Mountains were caused by ___collision__ between ___India__________ and Asia. 11. ___Folds____ are the most common ductile response to stress on rocks in the earth’s crust. 12. ___Faults___ are the most common brittle response to stress on rocks in the earth’s crust. 13. What types of faults are depicted in the cross section shown above? ___thrust_______ faults. Name _______________________________ GG 101 Exam 2 Page 3 14. The structure shown in the above diagram is a(n) ____anticline_____. 15. The name of a fold that occurs in an area of intense deformation where one limb of the fold has been tilted beyond the vertical is called a(n) ____overturned____ fold. -

Sedimentary Test 2 Review Guide Making Sedimentary Rocks 1

Name: KEY Unit III: Section 3: Sedimentary Processes Earth & Environmental Systems Science Test 2 Review Guide Sedimentary Test 2 Review Guide Making Sedimentary Rocks 1. What vocabulary word describes turning sediment into solid rock? Lithification = compaction + cementation 2. List and describe the processes to form sediment and then a sedimentary rock in order? - Weathering – breaking down - Erosion – moving/transporting sediment - Deposition – putting sediment into place Sediment MADE! Lithification: Turning sediment into a solid rock -Compaction – generally through burial and reduces pore space -Cementation – gluing sediment together using a mineral water solution Sedimentary Rock MADE! 3. What acts as glue to form Clastic and Bioclastic textured sedimentary rocks? Water moves through soil and rocks and dissolves minerals along the way. The mineral water solution settles in the sediment, the water evaporates, and the minerals are left behind to bind sediment. Uniformitarianism and Stratigraphy 4. What geological principle states that the same processes that operate today also operated in the past? Uniformitarianism – James Hutton 5. List and describe the 3 laws of Stratigraphy: -Law of Horizontal Deposition – Sediment is deposited and lithified in flat layers -Law of Superposition – oldest layers are on the bottom and youngest is on the top -Law of Cross-cutting – anything that cuts across sedimentary layers (faults or igneous intrusions) are younger than the layers that they cut across 6. What is an unconformity? Any process that disturbs sedimentary layers 7. List and describe the 3 types of unconformities: -Angular – beds are tilted (by plate tectonics), weathered and eroded, and new beds are placed on top at a different angle -Nonconformity – Igneous beds eat through sedimentary beds from the bottom -Disconformity – Sedimentary beds are missing due to weathering and erosion generally drawn as a straight squiggly line. -

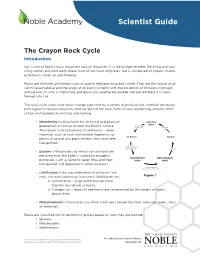

Scientist Guide the Crayon Rock Cycle

Scientist Guide The Crayon Rock Cycle Introduction Soil is one of Earth’s most important natural resources. It is the bridge between the living and non- living worlds and ultimately where most of our food originates. Soil is composed of organic materi- al (humus), water, air and minerals. Rocks are mixtures of minerals such as quartz, feldspar, mica and calcite. They are the source of all soil mineral material and the origin of all plant nutrients with the exception of nitrogen, hydrogen and carbon. As rock is chemically and physically weathered, eroded and precipitated, it is trans- formed into soil. The rock cycle shows how rocks change over time by a variety of physical and chemical processes (see Figure 1). Natural processes that are part of the rock cycle include weathering, erosion, lithifi- cation, metamorphism, melting and cooling. • Weathering involves both the chemical and physical IGNEOUS ROCK Weathering breakdown of rock at or near the Earth’s surface. and Erosion Cooling This results in accumulation of sediments – loose materials, such as rock and mineral fragments, or Sediment Magma pieces of animal and plant remains that have been transported. Lithification (Compaction and Cementation) Melting • Erosion is the process by which soil and rock are removed from the Earth’s surface by exogenic SEDIMENTARY METAMORPHIC processes, such as wind or water flow, and then ROCK ROCK transported and deposited in other locations. Metamorphism (Heat and/or Pressure) • Lithification is the transformation of sediment into rock. The main processes involved in lithification are: Figure 1. o Cementation – large sediments are held together by natural cements. -

The Relation Between Mantle Dynamics and Plate Tectonics

The History and Dynamics of Global Plate Motions, GEOPHYSICAL MONOGRAPH 121, M. Richards, R. Gordon and R. van der Hilst, eds., American Geophysical Union, pp5–46, 2000 The Relation Between Mantle Dynamics and Plate Tectonics: A Primer David Bercovici , Yanick Ricard Laboratoire des Sciences de la Terre, Ecole Normale Superieure´ de Lyon, France Mark A. Richards Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of California, Berkeley Abstract. We present an overview of the relation between mantle dynam- ics and plate tectonics, adopting the perspective that the plates are the surface manifestation, i.e., the top thermal boundary layer, of mantle convection. We review how simple convection pertains to plate formation, regarding the aspect ratio of convection cells; the forces that drive convection; and how internal heating and temperature-dependent viscosity affect convection. We examine how well basic convection explains plate tectonics, arguing that basic plate forces, slab pull and ridge push, are convective forces; that sea-floor struc- ture is characteristic of thermal boundary layers; that slab-like downwellings are common in simple convective flow; and that slab and plume fluxes agree with models of internally heated convection. Temperature-dependent vis- cosity, or an internal resistive boundary (e.g., a viscosity jump and/or phase transition at 660km depth) can also lead to large, plate sized convection cells. Finally, we survey the aspects of plate tectonics that are poorly explained by simple convection theory, and the progress being made in accounting for them. We examine non-convective plate forces; dynamic topography; the deviations of seafloor structure from that of a thermal boundary layer; and abrupt plate- motion changes. -

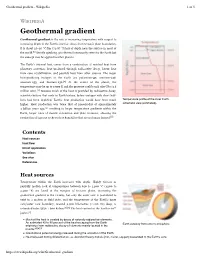

Geothermal Gradient - Wikipedia 1 of 5

Geothermal gradient - Wikipedia 1 of 5 Geothermal gradient Geothermal gradient is the rate of increasing temperature with respect to increasing depth in the Earth's interior. Away from tectonic plate boundaries, it is about 25–30 °C/km (72-87 °F/mi) of depth near the surface in most of the world.[1] Strictly speaking, geo-thermal necessarily refers to the Earth but the concept may be applied to other planets. The Earth's internal heat comes from a combination of residual heat from planetary accretion, heat produced through radioactive decay, latent heat from core crystallization, and possibly heat from other sources. The major heat-producing isotopes in the Earth are potassium-40, uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232.[2] At the center of the planet, the temperature may be up to 7,000 K and the pressure could reach 360 GPa (3.6 million atm).[3] Because much of the heat is provided by radioactive decay, scientists believe that early in Earth history, before isotopes with short half- lives had been depleted, Earth's heat production would have been much Temperature profile of the inner Earth, higher. Heat production was twice that of present-day at approximately schematic view (estimated). 3 billion years ago,[4] resulting in larger temperature gradients within the Earth, larger rates of mantle convection and plate tectonics, allowing the production of igneous rocks such as komatiites that are no longer formed.[5] Contents Heat sources Heat flow Direct application Variations See also References Heat sources Temperature within the Earth -

SUBMERGENCE and EMERGENCE of Rock Layers with Respect to Sea Level

SUBMERGENCE AND EMERGENCE of Rock Layers With Respect to Sea Level The building up and wearing away of Earth's Crust. Follow the progression of illustrations to see the roles that submergence and emergence of rock layers play in both the addition of rock material to earth's surface as well as its removal. The Key: Be sure to look at the key before observing the Illustration 1: Sedimentary Rocks are typically layered series of illustrations. horizontally and the Law of Superposition dictates that, Notice that not only do symbols exist for sandstone, shale unless overturning of rock layers has occurred, the oldest and conglomerate, but also for the loose sediments that rock layers are towards the bottom of a rock column while will eventually lithify to become these rock types. the youngest layers are at the top. This illustration depicts layers of sedimentary shale, sandstone and limestone, exposed at earth's surface. Illustration 2: The rock layers have been submerged, Illustration 3: Over time the processes of compaction possibly due to crustal movement or to a rise in sea level. and cementation will lithify these loose sediments turning All rock layers are now underwater and there exists the them into sedimentary rocks. The newly lithified rock possibility for additional, loose sediments to be deposited layer will be on top of the original layers shown in on top of the preexisting layers. Illustration 1 and it will be the youngest layer by L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 comparison. Notice the unconformity in this illustration. The unconformity is evidenced by the wavy, eroded top surface of a rock layer. -

Meulemans 2020

Urban Pedogeneses. The Making of City Soils from Hard Surfacing to the Urban Soil Sciences Germain Meulemans To cite this version: Germain Meulemans. Urban Pedogeneses. The Making of City Soils from Hard Surfacing to the Urban Soil Sciences. Environmental Humanities, [Kensington] N.S.W.: Environmental Humanities Programme University of New South Wales, 2020, 12 (1), pp.250-266. 10.1215/22011919-8142330. hal-02882863 HAL Id: hal-02882863 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02882863 Submitted on 27 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Urban Pedogeneses The Making of City Soils from Hard Surfacing to the Urban Soil Sciences GERMAIN MEULEMANS Centre Alexandre-Koyré, IFRIS, France Abstract This article examines the rise of urban soils as a topic of scientificinquiryandeco- logical engineering in France, and questions how new framings of soil as a material that can be designed reconfigure relationships between urban life and soils in a context of fast- growing cities. As a counterpoint to the current situation, the article first examines how the hard-surfacing of Paris, in the nineteenth century, sought to background the vital qualities of soils in urban areas, making their absence seem perfectly stable and natural. -

Mantle Convection in Terrestrial Planets

MANTLE CONVECTION IN TERRESTRIAL PLANETS Elvira Mulyukova & David Bercovici Department of Geology & Geophysics Yale University New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8109, USA E-mail: [email protected] May 15, 2019 Summary surfaces do not participate in convective circu- lation, they deform in response to the underly- All the rocky planets in our Solar System, in- ing mantle currents, forming geological features cluding the Earth, initially formed much hot- such as coronae, volcanic lava flows and wrin- ter than their surroundings and have since been kle ridges. Moreover, the exchange of mate- cooling to space for billions of years. The result- rial between the interior and surface, for exam- ing heat released from planetary interiors pow- ple through melting and volcanism, is a conse- ers convective flow in the mantle. The man- quence of mantle circulation, and continuously tle is often the most voluminous and/or stiffest modifies the composition of the mantle and the part of a planet, and therefore acts as the bottle- overlying crust. Mantle convection governs the neck for heat transport, thus dictating the rate at geological activity and the thermal and chemical which a planet cools. Mantle flow drives geo- evolution of terrestrial planets, and understand- logical activity that modifies planetary surfaces ing the physical processes of convection helps through processes such as volcanism, orogene- us reconstruct histories of planets over billions sis, and rifting. On Earth, the major convective of years after their formation. currents in the mantle are identified as hot up- wellings like mantle plumes, cold sinking slabs and the motion of tectonic plates at the surface. -

Why and How Do We Study Sediment Transport? Focus on Coastal Zones and Ongoing Methods

water Editorial Why and How Do We Study Sediment Transport? Focus on Coastal Zones and Ongoing Methods Sylvain Ouillon ID LEGOS, Université de Toulouse, IRD, CNES, CNRS, UPS, 14 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France; [email protected]; Tel.: +33-56133-2935 Received: 22 February 2018; Accepted: 22 March 2018; Published: 27 March 2018 Abstract: Scientific research on sediment dynamics in the coastal zone and along the littoral zone has evolved considerably over the last four decades. It benefits from a technological revolution that provides the community with cheaper or free tools for in situ study (e.g., sensors, gliders), remote sensing (satellite data, video cameras, drones) or modelling (open source models). These changes favour the transfer of developed methods to monitoring and management services. On the other hand, scientific research is increasingly targeted by public authorities towards finalized studies in relation to societal issues. Shoreline vulnerability is an object of concern that grows after each marine submersion or intense erosion event. Thus, during the last four decades, the production of knowledge on coastal sediment dynamics has evolved considerably, and is in tune with the needs of society. This editorial aims at synthesizing the current revolution in the scientific research related to coastal and littoral hydrosedimentary dynamics, putting into perspective connections between coasts and other geomorphological entities concerned by sediment transport, showing the links between many fragmented approaches of the topic, and introducing the papers published in the special issue of Water on “Sediment transport in coastal waters”. Keywords: sediment transport; cohesive sediments; non cohesive sediments; sand; mud; coastal erosion; sedimentation; morphodynamics; suspended particulate matter; bedload 1.