Jbaa 123, 5 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meetings of the Royal Society—Session 1889-90

1889-90.] Meetings of the Society. 411 Meetings of the Royal Society—Session 1889-90. Monday, 25ih November 1889. General Statutory Meeting. Election of Office-Bearers. P. xvii. 1. Monday, 2nd December 1889. Prof. Sir Douglas Maclagan, Vice-President, in the Chair. The following Communications were read:— 1. On the Transformation of Laplace's Coefficients. By Dr G. PLARR. Communicated by Professor TAIT. T. xxxvi. 19. 2. Preliminary Note on the Thermal Conductivity of Aluminium. J3y A. CRICHTON MITCHELL, Esq., B.Sc. 3. On Coral Eeefs and other Carbonate of Lime Formations in Modern Seas. By JOHN MURRAY, LL.D., and ROBERT IRVINE, F.C.S. (With Lantern Illustrations.) P. xvii. 79. The following Candidates for Fellowship were balloted for, and declared duly elected Fellows of the Society :— Prof. RALPH COPELAND, Astronomer-Royal for Scotland. G. A. Gibson, M.A. Monday, I6tk December 1889. Sir Arthur Mitchell, K.C.B., LL.D., Vice-President, in the Chair. A series of Photographs of Stars and Nebula;, presented by ISAAC ROBERTS, Esq. ; and Photographs of Lightning taken in Natal, presented by C. W. METHVEN, Esq., were exhibited. The following Communications were read :— 1. Note on Cayley's Demonstration of Pascal's Theorem. By THOMAS MUIR, M.A., LL.D. P. xvii. 18. 2. On Self-Conjugate Permutations. By THOMAS MDIR, M.A., LL.D. P. xvii. 7. 3. On a Rapidly Converging Series for the Extraction of the Square Boot. By THOMAS MDIR, M.A., LL.D. P. xvii. 14. 4. On some Quaternion Integrals. By Professor TAIT. 5. On the Glissette of a Hyperbola. -

Catalogue of Place Names in Northern East Greenland

Catalogue of place names in northern East Greenland In this section all officially approved, and many Greenlandic names are spelt according to the unapproved, names are listed, together with explana- modern Greenland orthography (spelling reform tions where known. Approved names are listed in 1973), with cross-references from the old-style normal type or bold type, whereas unapproved spelling still to be found on many published maps. names are always given in italics. Names of ships are Prospectors place names used only in confidential given in small CAPITALS. Individual name entries are company reports are not found in this volume. In listed in Danish alphabetical order, such that names general, only selected unapproved names introduced beginning with the Danish letters Æ, Ø and Å come by scientific or climbing expeditions are included. after Z. This means that Danish names beginning Incomplete documentation of climbing activities with Å or Aa (e.g. Aage Bertelsen Gletscher, Aage de by expeditions claiming ‘first ascents’ on Milne Land Lemos Dal, Åkerblom Ø, Ålborg Fjord etc) are found and in nunatak regions such as Dronning Louise towards the end of this catalogue. Å replaced aa in Land, has led to a decision to exclude them. Many Danish spelling for most purposes in 1948, but aa is recent expeditions to Dronning Louise Land, and commonly retained in personal names, and is option- other nunatak areas, have gained access to their al in some Danish town names (e.g. Ålborg or Aalborg region of interest using Twin Otter aircraft, such that are both correct). However, Greenlandic names be - the remaining ‘climb’ to the summits of some peaks ginning with aa following the spelling reform dating may be as little as a few hundred metres; this raises from 1973 (a long vowel sound rather than short) are the question of what constitutes an ‘ascent’? treated as two consecutive ‘a’s. -

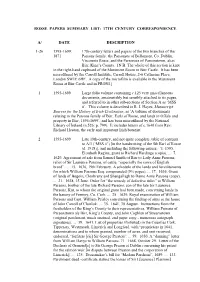

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Stars and Satellites Mary Brück

Mary Brück Women in Early British and Irish Astronomy Stars and Satellites 123 Women in Early British and Irish Astronomy Mary Brück Women in Early British and Irish Astronomy Stars and Satellites Mary Brück ISBN 978-90-481-2472-5 e-ISBN 978-90-481-2473-2 DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-2473-2 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009931554 c Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) For my sisters (nees´ Conway) Eithne, Meadhbh and Aoife Foreword The role of women in the growth of science has become an important area of modern historical scholarly research. And as far as the study of the role of women in astron- omy is concerned, Dr. Mary Br¨uck is an established and illustrious pioneer, with an international reputation and acclaimed books and articles already to her credit. Her present book, Stars and Satellites, brings together many figures who worked over a 300-year time scale, and whose relationship with astronomy ranged from informed assistants to independent researchers to major writers and interpreters of contem- porary astronomy to, eventually, paid professionals. -

Journal the Future of the City Observatory

10/07/2018 ASE Journal No. 49 Astronomical Society of Edinburgh Journal No. 49 - October 2005 Nora Jenkinson with Harperdean Astronomical Society members, c. 1990. The future of the City Observatory http://www.astronomyedinburgh.org/publications/journals/49/all.shtml 1/12 10/07/2018 ASE Journal No. 49 For some time the Society has been anxious about the state of the Playfair Building which houses the Cooke refractor and also the other Building in which we have our monthly meetings. The buildings are leased from the City Council. The buildings are deteriorating and may become unfit for any use in the not too distant future. The City has plans to redevelop Calton Hill, including the buildings of astronomical interest. To review progress towards the completion of these plans myself and Alan Ellis met with City Council officials on 13th September 2005. Chairing the meeting was Lynne Halfpenny, Head of Museum and Arts, City of Edinburgh Council. We were informed that the Council has appointed architects and hopes to set up a management group within the next six months which will develop a plan. Once the plan is completed funding will be secured (hopefully) and work can commence. Work on the whole site may not be completed until 2010/2011. The ASE will be invited to be represented on the management group. The ASE now has the choice of two possible scenarios. One scenario is separating ourselves from the City Observatory because of its deteriorating state and because its upkeep is expensive. Rates and electricity are significant costs which result in our relatively high membership fee. -

Biographical Index of Former RSE Fellows 1783-2002

FORMER RSE FELLOWS 1783- 2002 SIR CHARLES ADAM OF BARNS 06/10/1780- JOHN JACOB. ABEL 19/05/1857- 26/05/1938 16/09/1853 Place of Birth: Cleveland, Ohio, USA. Date of Election: 05/04/1824. Date of Election: 03/07/1933. Profession: Royal Navy. Profession: Pharmacologist, Endocrinologist. Notes: Date of election: 1820 also reported in RSE Fellow Type: HF lists JOHN ABERCROMBIE 12/10/1780- 14/11/1844 Fellow Type: OF Place of Birth: Aberdeen. ROBERT ADAM 03/07/1728- 03/03/1792 Date of Election: 07/02/1831. Place of Birth: Kirkcaldy, Fife.. Profession: Physician, Author. Date of Election: 28/01/1788. Fellow Type: OF Profession: Architect. ALEXANDER ABERCROMBY, LORD ABERCROMBY Fellow Type: OF 15/10/1745- 17/11/1795 WILLIAM ADAM OF BLAIR ADAM 02/08/1751- Place of Birth: Clackmannanshire. 17/02/1839 Date of Election: 17/11/1783. Place of Birth: Kinross-shire. Profession: Advocate. Date of Election: 22/01/1816. Fellow Type: OF Profession: Advocate, Barrister, Politician. JAMES ABERCROMBY, BARON DUNFERMLINE Fellow Type: OF 07/11/1776- 17/04/1858 JOHN GEORGE ADAMI 12/01/1862- 29/08/1926 Date of Election: 07/02/1831. Place of Birth: Ashton-on-Mersey, Lancashire. Profession: Physician,Statesman. Date of Election: 17/01/1898. Fellow Type: OF Profession: Pathologist. JOHN ABERCROMBY, BARON ABERCROMBY Fellow Type: OF 15/01/1841- 07/10/1924 ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL ADAMS Date of Election: 07/02/1898. Date of Election: 19/12/1910. Profession: Philologist, Antiquary, Folklorist. Profession: Consulting Engineer. Fellow Type: OF Notes: Died 1918-19 RALPH ABERCROMBY, BARON DUNFERMLINE Fellow Type: OF 06/04/1803- 02/07/1868 JOHN COUCH ADAMS 05/06/1819- 21/01/1892 Date of Election: 19/01/1863. -

1 the Astronomizings of Dr. Anderson and the Curious Case of His

1 The astronomizings of Dr. Anderson and the curious case of his disappearing nova Jeremy Shears Abstract Dr. Thomas David Anderson (1853 –1932) was a Scottish amateur astronomer famed for his discovery of two bright novae: Nova Aurigae 1891 and Nova Persei 1901. He also discovered more than 50 variable stars as well as making independent discoveries of Nova Aquilae 1918 and comet 17P/Holmes in 1892. At the age of seventy, in 1923, he reported his discovery of a further nova, this time in Cygnus. This was set to be the culmination of a lifetime devoted to scanning the night sky, but unfortunately no one was able to confirm it. This paper discusses Anderson‟s life leading up to the discovery and considers whether it was real or illusory. Introduction In the early hours of the morning of 9 May 1923, the 70 year old amateur astronomer Dr. Thomas David Anderson (1853 –1932; Figure 1) was carefully examining star fields in Cygnus as part of a nova search programme that he had been conducting for nearly half his life. Suddenly he came upon an unfamiliar star of about the fifth or sixth magnitude. Unfortunately, before he had time to make more detailed observations of the star, his view was obscured by clouds. Nevertheless he sent a telegram to the Royal Observatory Greenwich to report his observation and the approximate location of the object. The following day, photographs taken by the distinguished Greenwich astronomer and a founding member of the BAA, Dr W.H. Steavenson (1894 - 1975), revealed no trace of any new object brighter than about twelfth magnitude. -

Dudley Holdings Arranged by Main Entry 12/23/03 Deutsche Akademie

Dudley Holdings Arranged by Main Entry 12/23/03 Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. CATALOGUE ZU DEN 24 STUDEN DER AKADEMISCHEN STERNKARTEN FUR 150 SUDLICHER BIS 150 NORDLICHER ABWEICHUNG BEARB. VON VERSCHIEDENEN ASTRONOMEN / HRSG. VON DER K. AKADEMIE. Berlin : Gedruckt in der Druckerei der K. Akademie.., in commission in F. Dummler's Verlags-Buchhandlung, 1859. QB65 .A22 1859. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. GESCHICHTE DES FIXSTERNHIMMELS ; ENTHALTEND DIE STERNORTER DER KATALOGE DES 18. UND 19. JAHRHUNDERTS / HERAUSGEGEBEN VON DER PREUSSISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN. Karlsruhe : G. Braun, 1922- QB6 .P7. DeVorkin, David H., 1944- THE HISTORY OF MODERN ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS : A SELECTED, ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY / DAVID H. DEVORKIN. New York : Garland, 1982. QB 15.D48 1982. Dick, Thomas, 1774-1857. THE SOLAR SYSTEM. London : Religious Tract Society ; Philadelphia : American Sunday- School Union, 1846. Dicke, Robert H. (Robert Henry) GRAVITATION AND THE UNIVERSE [BY] ROBERT H. DICKE. Philadelphia, American Philosophical Society, 1970. QC178.D5. Dickson, Leonard Eugene, 1874-1954. MODERN ALGEBRAIC THEORIES, BY LEONARD E. DICKSON. Chicago, New York [etc.] B. H. Sanborn & co., 1930. QA 154 D5. A DICTIONARY OF ASTRONOMY / EDITED BY IAN RIDPATH. Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 1997. QB14 .D52 1997. DICTIONARY OF PHYSICS AND MATHEMATICS ABBREVIATIONS, SIGNS, AND SYMBOLS. EDITOR: DAVID D. POLON. MANAGING EDITOR: HERBERT W. REICH. PROJECT DIRECTOR : MARJORIE B. WITTY. New York, Odyssey Press [c1965]. REF QC5.D55. DICTIONARY OF THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE / EDITED BY W.F. BYNUM, E.J. BROWNE, ROY PORTER. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, c1981. REF Q125.B98. Dienes, G. J. (George Julian), 1918- STUDIES IN RADIATION EFFECTS.