The Annenberg Challenge: Lessons and Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

The Annenberg Foundation

Trustees Gregory Annenberg Weingarten, Charles Anenberg Weingarten, Wallis Annenberg and Lauren Bon (photo by Jim McHugh) The Annenberg Foundation Courtesy of Southern California Grantmakers By James Klein, James Klein Consulting While global in scope, the Annenberg Foundation has a special relationship with the Los Angeles area. The Annenberg Foundation’s Radnor, Pennsylvania headquarters was established with its creation in 1989, while the Southern California office didn’t become fully operational until 2003. Four out of five of the Foundation’s Trustees live in Los Angeles County, however, and work from its Century City office. While both locations accept grant submissions from anywhere in the world, the Trustees’ presence in the region and close involvement in the organization naturally leads to support for local projects. “Our perspective is a Los Angeles one,” says Leonard Aube, Managing Director of the Annenberg Foundation’s Southern California operations. “Those of us here today were not transferred from the Radnor, Pennsylvania office. We were brought on under Wallis Annenberg’s leadership to support her philanthropy in the region primarily.” The Annenberg Foundation is the 11th largest nationwide in giving, authorizing over $250 million in grants to more than 500 nonprofit organizations in its most recently completed fiscal year. The institution ranks 18th overall in total assets nationwide with more than $2.5 billion. Though sizable, the Annenberg Foundation is a family affair. Publisher, diplomat, and philanthropist Walter H. Annenberg founded the organization in 1989. His wife, Leonore Annenberg, became President and Chairman after his passing in 2002. His daughter, Wallis Annenberg, emerged as Vice President. -

Caltech News

Volume 16, No.7, December 1982 CALTECH NEWS pounds, became optional and were Three Caltech offered in the winter and spring. graduate programs But under this plan, there was an overlap in material that diluted the rank number one program's efficiency, blending per in nationwide survey sons in the same classrooms whose backgrounds varied widely. Some Caltech ranked number one - students took 3B and 3C before either alone or with other institutions proceeding on to 46A and 46B, - in a recent report that judged the which focused on organic systems, scholastic quality of graduate pro" while other students went directly grams in mathematics and science at into the organic program. the nation's major research Another matter to be addressed universities. stemmed from the fact that, across Caltech led the field in geoscience, the country, the lines between inor and shared top rankings with Har ganic and organic chemistry had ' vard in physics. The Institute was in become increasingly blurred. Explains a four-way tie for first in chemistry Professor of Chemistry Peter Der with Berkeley, Harvard, and MIT. van, "We use common analytical The report was the result of a equipment. We are both molecule two-year, $500,000 study published builders in our efforts to invent new under the sponsorship of four aca materials. We use common bonds for demic groups - the American Coun The Mead Laboratory is the setting for Chemistry 5, where Carlotta Paulsen uses a rotary probing how chemical bonds are evaporator to remove a solvent from a synthesized product. Paulsen is a junior majoring in made and broken." cil of Learned Societies, the American chemistry. -

For Immediate Release Annenberg Foundation in Association With

For Immediate Release Annenberg Foundation in association with KCRW presents COUNTRY IN THE CITY Three Free Concerts inspired by Annenberg Space for Photography’s current exhibit, Country: Portraits of an American Sound Performances by GREGG ALLMAN, SHELBY LYNNE, WYNONNA & THE BIG NOISE and more LOS ANGELES, CA (June 3, 2014) The Annenberg Foundation today announced Country in the City, an all ages, free concert series inspired by the Annenberg Space for Photography’s current exhibition, Country: Portraits of an American Sound. Country in the City will take place on three Saturday evenings, July 19, July 26 and August 2, in Century Park in Century City on the lawn adjacent to the Annenberg Space for Photography. Presented in association with KCRW, the concerts will be offered free to the public. Each of the concerts will require separate, advance online registration at KCRW.com. Emails will be sent to those who have registered with detailed instructions in advance of their arrival at the concert site. RSVP is required for entry. No tickets are needed. However, registered guests must collect wristbands upon arrival at check in to gain access to concerts. The talent lineup is as follows: July 19: GREGG ALLMAN, Sturgill Simpson July 26: SHELBY LYNNE, Jamestown Revival August 2: WYNONNA & THE BIG NOISE, Nikki Lane Gregg Allman, who is a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee as a founding member of the Allman Brothers Band, headlines the first evening on July 19. Named one of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time’’ by Rolling Stone, Allman recently released All My Friends: Celebrating the Songs & Voice of Gregg Allman, a live album that include guest performances by many of his contemporaries such as Trace Adkins, Jackson Browne, Martina McBride, Vince Gill, John Hiatt, Widespread Panic and many more. -

Annenberg's $27.5 Million Endowment

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday, December 19, 2000 Volume 47 Number 16 www.upenn.edu/almanac/ Annenberg’s $27.5 Million Endowment: Institute for Adolescent Risk Communication agers and ensure that they become healthy, happy “Most of these campaigns, and the research and productive adults,” President Rodin said. accompanying them, have concentrated on re- “The new Institute will harness the formidable ducing one risky behavior at a time,” she said. efforts already underway in this area at the “What’s lost in this ‘single issue’ approach is Annenberg Public Policy Center and provide whether, for example, a successful anti-smoking important new opportunities for scholars to col- campaign results in a decreased perception of laborate with colleagues at other schools and the risks of drugs, or how the effectiveness of a centers at Penn who are working on issues of particular campaign changes as very young teens adolescent behavior.” grow older. What works for one campaign may An additional $2.5 million will be used to actually be harmful to another. establish the Walter and Leonore Annenberg “The new Institute will enable us to have, for Walter Annenberg Leonore Annenberg Chair for the Director of the Public Policy Center the first time, an integrated focus on adolescent at Penn’s Annenberg School for Communication. risk communications that will leverage our exper- A $25 million endowment from the The chair will be held by the director of the Center. tise and resources for the best possible results.” Annenberg Foundation of St. Davids, will be The Honorable Leonore Annenberg, Vice Dean Jamieson said that the Institute would used to establish a new Institute for Adolescent Chairman of the Annenberg Foundation, said: also provide additional opportunities for under- Risk Communication at Penn’s Annenberg Pub- “With our nation increasingly focused on minimiz- graduate and graduate student research in ado- lic Policy Center, according to an announcement ing adolescent risk, this new Institute is poised to lescent risk. -

When Victims Rule

1 24 JEWISH INFLUENCE IN THE MASS MEDIA, Part II In 1985 Laurence Tisch, Chairman of the Board of New York University, former President of the Greater New York United Jewish Appeal, an active supporter of Israel, and a man of many other roles, started buying stock in the CBStelevision network through his company, the Loews Corporation. The Tisch family, worth an estimated 4 billion dollars, has major interests in hotels, an insurance company, Bulova, movie theatres, and Loliards, the nation's fourth largest tobacco company (Kent, Newport, True cigarettes). Brother Andrew Tisch has served as a Vice-President for the UJA-Federation, and as a member of the United Jewish Appeal national youth leadership cabinet, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Israel Political Action Committee, among other Jewish organizations. By September of 1986 Tisch's company owned 25% of the stock of CBS and he became the company's president. And Tisch -- now the most powerful man at CBS -- had strong feelings about television, Jews, and Israel. The CBS news department began to live in fear of being compromised by their boss -- overtly, or, more likely, by intimidation towards self-censorship -- concerning these issues. "There have been rumors in New York for years," says J. J. Goldberg, "that Tisch took over CBS in 1986 at least partly out of a desire to do something about media bias against Israel." [GOLDBERG, p. 297] The powerful President of a major American television network dare not publicize his own active bias in favor of another country, of course. That would look bad, going against the grain of the democratic traditions, free speech, and a presumed "fair" mass media. -

View September 2018

TheThe ViewViewView September 2018 Kohlers are 83 Years Married Story on Page 10 Photo by Robert DeLaurenti CONTACT INFORMATION SUN CITY SHADOW HILLS Sun City Shadow Hills Community Association COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION 80-814 Sun City Boulevard, Indio, CA 92203 Hours of Operation www.scshca.com · 760-345-4349 Association Office Homeowner Association (HOA). Ext. 1 Monday – Friday · 9 AM – 12 PM, 1 – 4 PM Montecito Clubhouse Fax . 760-772-9891 First Saturday of the Month · 8 AM – 12 PM Montecito Clubhouse . Ext. 2120 Lifestyle Desk Daily · 8 AM – 5 PM Montecito Fitness Center . Ext. 2111 Santa Rosa Clubhouse Fax. 760-342-5976 Montecito Clubhouse Daily · 6 AM – 10 PM Santa Rosa Clubhouse. Ext. 2201 Montecito Fitness Center Shadow Hills Golf Club South . Ext. 2305 Daily · 5 AM – 8 PM Shadow Hills Golf Club North . Ext. 2211 Santa Rosa Clubhouse Shadows Restaurant . Ext. 2311 Daily · 6 AM – 9 PM Jefferson Front Gate (Phases 1 & 2) . 760-345-4458 Shadows Restaurant Avenue 40 Front Gate (Phase 3) . 760-342-4725 Sunday – Thursday · 8 AM – 6 PM Friday – Saturday · 8 AM – 8 PM Rich Smetana, General Manager Breakfast: 8 – 11 AM [email protected] . Ext. 2102 Lunch/Small Plates: 11 AM – 6 PM Tyler Ingle, Controller Happy Hour: 3 – 6 PM [email protected]. Ext. 2203 Golf Snack Bar Mark Galvin, Community Safety Director 5:30 – 11 AM [email protected] . Ext. 2202 Santa Rosa Bistro Jesse Barragan, Facilities Maintenance Director Daily · 6 AM – 1 PM [email protected] . Ext. 2403 Limited menu available through September 23; Connie King, Lifestyle Director Closed September 24 – October 12 [email protected] . -

Bicentennial - General (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 65, folder “Bicentennial - General (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. .. Digitized from Box 65 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ,,.,T ......................... ,.. ,._, ••• tw -,_................. ...... ef .........., ...... II.. ......... ftle •••••• lot,... an__. ........... ........w .......... ,.... ...... ..,..c........... ef •• •tlaa•e lllca••••I•L ,..,. ... _..... ..., .. ,... .............. .... .....•••.......... ..................... ..., ........... , ...... w. ....... ,.. a~w..- .. ~.................. ..... ............. ,.. .......... ... ,.., ..................... ......... , ......... ,.. ... ,_ ... Ill••••• ..• I celeltw•tl•• ...... ,. , ... o. ....... , •• ............... c._._ .............. DlnatiR OMc•., .................:.a oae••••.._. ....... Me••• ...... IIlii bee: Anne Armstrong~ JOM:ec Boston200"' Office of the Boston Bicentennial Kevin H. White Mayor Katharine D. Kane Director September 23, 1974 Honorable John 0. Marsh Counsellor to the President The White House Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. Marsh: Tex McCrary has asked me to send you the enclosed brochures on Boston's Liberty Plantree Program. He has told me of your long interest in the Liberty Tree, and we certainly are happy that the idea of the Plantree Program is spreading through the country. -

Photo Report

Richard Nixon Presidential Library: Photo Report ● 1895-1. Richard Nixon's Mother, Hannah Milhous Nixon. Jennings Co., Indiana. B&W. Source: copied into White House Photo Office. Alternate Numer: B-0141 Hannah Milhous Nixon ● 18xx-1. Richard Nixon's paternal grandfather, Samuel Brady Nixon. B&W. Samuel Brady Nixon ● 1916-1. Family portrait with Richard Nixon (age 3). 1916. California. B&W. Harold Nixon, Frank Nixon, Donald Nixon, Hannah Nixon, Richard Nixon ● 1917-1. Portrait of Richard Nixon (age 4). 1917. California. B&W. Richard Nixon, Portrait ● 1930-1. Richard Nixon senior portrait (age 17), as appeared in the Whittier High School annual. 1930. Whittier, California. B&W. Richard Nixon, Yearbook, Portrait, Senior, High School, Whittier High School ● 1945-1. Formal portrait of Richard Nixon in uniform (Lieutenant Commander, USN). Between October, 1945 (date of rank) and March, 1946 (date of discharge). B&W. Richard Nixon, Portrait, Navy, USN, Uniform ● 1946-1. Richard Nixon, candidate for Congress, discusses the election with the Republican candidates for Attorney General Fred Howser and for California State Assemblyman Montivel A. Burke at a GOP rally in honor of Senator Knowland (R-Ca). 1946. El Monte, California. B&W. Source: Photo by Dot and Larry, 2548 Ivar Avenue, Garvey, California, Phone Atlantic 15610 Richard Nixon, Fred Howser, Montivel Burke, Campaign, Knowland ● 1946-2. Congressman Carl Hinshaw and Richard Nixon shake hands during a campaign. 1946. B&W. Carl Hinshaw, Richard Nixon, Campaign, Handshake ● 1946-3. Senator William F. Knowland (R-CA) being greeted by Claude Larrimer (seated) of Whittier at a GOP rally (barbeque/entertainment) in honor of the former. -

Selections from the Gift Collection of Walter and Leonore

Graduated brass weights cast in the shape of elephants (page 47). Previous page A sampling of decorative boxes that the Annenbergs received as gifts over the decades. TREASURES AT SUNNYLANDS: SELECTIONS FROM THE GIFT COLLECTION OF WALTER & LEONORE ANNENBERG January 25, 2015 through January 17, 2016 by Anne Rowe Text, design, and all images copyright © The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands 2014. An illustration of Washington, D.C. from First published in 2014 by The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands, the interior of the decoupage presentation 71231 Tamarisk Lane, Rancho Mirage, CA 92270, United States of America. box given to the Annenbergs by All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized, in any form or by any Jay and Sharon Rockefeller (page 51). means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014951183 ISBN: 978-0-9858429-9-4. Printed in the United States of America. Book and cover design by JCRR Design. Contents The Annenberg Retreat at Sunnylands by Geoffrey Cowan page 6 Walter and Leonore Annenberg by Janice Lyle, Ph.D. page 6 Treasures at Sunnylands by Anne Rowe pages 7 – 17 Gifts from Presidents & First Ladies pages 18 – 27 Gifts from Royalty pages 28 – 33 Gifts from Diplomats pages 34 – 43 Gifts from Business Leaders pages 44 – 53 Gifts from Entertainers pages 54 – 59 Gifts from Family pages 60 – 63 Acknowledgments page 64 This eighteenth-century silver creamer was a gift from David Rockefeller (page 45). 5 The Annenberg Retreat at Sunnylands Walter and Leonore Annenberg For more than forty years, Sunnylands served as Sunnylands was the winter home of Walter and an oasis for presidents of the United States, other Leonore Annenberg. -

Newspapers, Suburbanization, and Social Change in the Postwar Philadelphia Region, 1945-1982

COVERING SUBURBIA: NEWSPAPERS, SUBURBANIZATION, AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN THE POSTWAR PHILADELPHIA REGION, 1945-1982 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by James J. Wyatt January, 2012 Examining Committee Members: Kenneth Kusmer, Advisory Chair, History Beth Bailey, History James Hilty, History Carolyn Kitch, External Member, Journalism ii © by James J. Wyatt 2012 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT My dissertation, “Covering Suburbia: Newspapers, Suburbanization, and Social Change in the Postwar Philadelphia Region, 1945-1982,” uses the Philadelphia metropolitan area as a representative case study of the ways in which suburban daily newspapers influenced suburbanites’ attitudes and actions during the post-World War II era. It argues that the demographic and economic changes that swept through the United States during the second half of the twentieth century made it nearly impossible for urban daily newspapers to maintain their hegemony over local news and made possible the rise of numerous profitable and competitive suburban dailies. More importantly, the dissertation argues that, serving as suburbanites’ preferred source for local news during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, enabled the suburban newspapers to directly influence the social, cultural, and physical development of the suburbs. Their emergence also altered the manner in which urban newspapers covered the news and played an instrumental role in the demise of several of the nation’s -

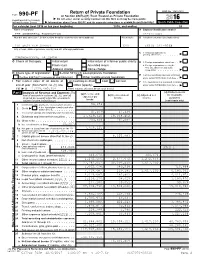

2016 Form 990-PF

Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µº Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2016 or tax year beginning , 2016, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE ANNENBERG FOUNDATION 23-6257083 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 101 WEST ELM STREET 640 (610) 341-9268 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption applicatmionm ism m m m m m I pending, check here CONSHOHOCKEN, PA 19428 m m I G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm hem rem anmd am ttamchm m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminamtedI Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminmatIion end of year (from Part II, col.