The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Is Queen Elizabeth II?

Who is Queen Elizabeth II? Elizabeth Alexandra Mary, later to become Queen Elizabeth II, was born on 21 April 1926 in Mayfair, London. She was the first child of The Duke and Duchess of York, who later became King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The Queen’s birthday is officially celebrated in Britain on the second Saturday of June each year. This special day is referred to as ‘The Trooping of the Colour’. The Queen is also known as the British Sovereign. Trooping of the Colour Elizabeth’s Family In 1936, King Edward VIII stepped down from the throne. Elizabeth’s father was crowned King George VI. Her mother became Queen Elizabeth, and Elizabeth and her sister Margaret were now Princesses. Elizabeth’s Childhood Princess Elizabeth was taught at home, not at school. • She studied art and music and enjoyed drama and swimming. • When she was 11, she joined the Girl Guides. • Elizabeth undertook her first public engagement on her 16th birthday, when she inspected the soldiers of the Grenadier Guards. The Royal Family Elizabeth got married in Westminster Abbey on 20th November 1947, when she was 21 years old. Her husband Prince Philip, also known as the Duke of Edinburgh, was the son of Prince Andrew of Greece. In 1948, the Queen’s first child Prince Charles was born. Two years later Princess Anne was born. Elizabeth would go on to have two more children, Prince Andrew and Prince Edward in 1960 and 1964. Elizabeth Becomes Queen In 1952, when she was just 25, Elizabeth’s father King George VI died. -

Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 27, folder “State Visits - Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 27 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN ~ . .,1. THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN A Profile On the Occasion of The Visit by The Emperor and Empress to the United States September 30th to October 13th, 1975 by Edwin 0. Reischauer The Emperor and Empress of japan on a quiet stroll in the gardens of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Few events in the long history of international relations carry the significance of the first visit to the United States of the Em peror and Empress of Japan. Only once before has the reigning Emperor of Japan ventured forth from his beautiful island realm to travel abroad. On that occasion, his visit to a number of Euro pean countries resulted in an immediate strengthening of the bonds linking Japan and Europe. -

Rechtsgeschichte Rechts R Geschichte G

Zeitschri des Max-Planck-Instituts für europäische Rechtsgeschichte Rechts R geschichte g Rechtsgeschichte www.rg.mpg.de http://www.rg-rechtsgeschichte.de/rg19 Rg 19 2011 267 – 276 Zitiervorschlag: Rechtsgeschichte Rg 19 (2011) http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg19/267-276 Heikki Pihlajamäki Translating German Administrative Law: The Case of Finland Dieser Beitrag steht unter einer Creative Commons cc-by-nc-nd 3.0 267 Translating German Administrative Law: TheCaseofFinland Legal translations The language of comparative law is replete with terms refer- ring to ways in which legal norms and ideologies move. While an overview of these is not appropriate in this article, I will take up one recent suggestion that I find particularly illuminating. Máximo such as Finland and Sweden, are Langer has proposed the term »legal translation«, through which full of such importers and, in the he hopes to highlight the fact that legal norms rarely remain nineteenth century, German legal unchanged when they are taken over by another legal system. science turned into one big export Legal norms need to be adjusted to their new legal, social, political, product. Active »exporters« of le- economic and cultural environments. The »translator« of the gal ideas are no rare birds, either; one need only think of the eager- norm, legal institution or legal ideology does, in fact, much of ness with which a host of Western the same work as a translator (or a reader) of a novel or a poem. law schools are currently expand- When works of literature are read or translated by a person ing their businesses in China. -

Russia on the Move-The Railroads and the Exodus from Compulsory Collectivism 1861-1914

Russia on the Move-The Railroads and the Exodus From Compulsory Collectivism 1861-1914 Sztern, Sylvia 2017 Document Version: Peer reviewed version (aka post-print) Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sztern, S. (2017). Russia on the Move-The Railroads and the Exodus From Compulsory Collectivism 1861- 1914. (2017 ed.). Printed in Sweden by Media-Tryck, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 Creative Commons License: Unspecified General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Russia on the Move The Railroads and the Exodus from Compulsory Collectivism 1861–1914 Sylvia Sztern DOCTORAL DISSERTATION by due permission of the School of Economics and Management, Lund University, Sweden. -

Swedish Royal Ancestry Book 4 1751-Present

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY SWEDISH ANCESTRY Recent Royalty (1751 - Present) INTRODUCTION Our Swedish ancestry is quite comprehensive as it covers a broad range of the history. For simplicity the information has been presented in four different books. Book 1 – Mythical to Viking Era (? – 1250) Book 2 – Folkunga Dynasty (1250 – 1523) Book 3 – Vasa Dynasty (1523 – 1751) Book 4 – Recent Royalty (1751 – Present) Book 4 covers the most recent history including the wars with Russia that eventually led to the loss of Finland to Russia and the emergence of Finland as an independent nation as well as the history of Sweden during World Wars I and II. A list is included showing our relationship with the royal family according to the lineage from Nils Kettilsson Vasa. The relationship with the spouses is also shown although these are from different ancestral lineages. Text is included for those which are highlighted in the list. Lars Granholm, November 2009 Recent Swedish Royalty Relationship to Lars Erik Granholm 1 Adolf Frederick King of Sweden b. 14 May 1710 Gottorp d. 1771 Stockholm (9th cousin, 10 times removed) m . Louisa Ulrika Queen of Sweden b. 24 July 1720 Berlin d. 16 July 1782 Swartsjö ( 2 2 n d c o u s i n , 1 1 times removed) 2 Frederick Adolf Prince of Sweden b. 1750 d. 1803 (10th cousin, 9 times removed) 2 . Sofia Albertina Princess of Sweden b, 1753 d. 1829 (10th cousin, 9 times removed) 2 . Charles XIII King of Sweden b. 1748 d. 1818 (10th cousin, 9 times removed) 2 Gustav III King of Sweden b. -

Nicholas Ascends the Throne

The Identification of Weakness: A Psycho Historical Analysis of Tsar Nicholas II Using the NEO-Personality Inventory Revised Exam By Keely Johnson Senior Capstone History 489 Dr. Patricia Turner Capstone Advisor Dr. Paulis Lazda Cooperating Professor Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Abstract Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was an unquestionable failure of a monarch. However, much of his demise was due to his lack of education and the accumulation of overpowering advisors that manipulated his weak mental and emotional characteristics. This paper identifies these characteristics through the analysis of Nicholas’ personal documents and compares them to the NEO-Personality Inventory Revised Exam in order to better understand why he failed miserably as Tsar. In a study conducted by Joyce E. Bono and Timothy A. Judge at the University of Iowa in 2000, it was found that evaluations of the Big Five personality characteristics correlated to leadership performance. This study was conducted using the NEO-Personality Inventory Revised exam, and was also applied to this research in order to better evaluate Nicholas II’s failed rule as Tsar of Russia. Through the analysis, it is clear that Nicholas’ possessed personality characteristics unsuitable for any leadership position. This research used interdisciplinary studies from the psychological sphere, thereby opening doors in the historical research field by using psycho historical analysis to highlight new viewpoints of previously researched material. 2 Acknowledgements This paper is the result of many elements working together in order to push me through this process, and for that I would like to thank them all. -

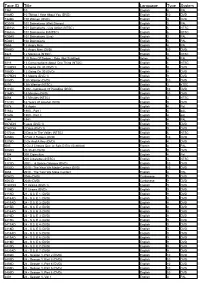

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Symbolism of the Longest Reigning Queen Elizabeth II From1952 To2017

الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبية Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Symbolism of the Longest Reigning Queen Elizabeth II from1952 to2017 Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in (LC) Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms. Leila BASSAID Mrs. Souad HAMIDI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Assia BENTAYEB Chairperson Mrs. Souad HAMIDI Supervisor Dr. Yahia ZEGHOUDI examiner Academic Year: 2016-2017 Dedication First of all thanks to Allah the most Merciful. Every challenging work needs self efforts as well as guidance of older especially those who were very close to our heart, my humble efforts and dedications to my sweet and loving parents: Ali and Soumya whose affection, love and prayers have made me able to get such success and honor, and their words of encouragement, support and push for tenacity ring in my ears. My two lovely sisters Manar and Ibtihel have never left my side and are very special, without forgetting my dearest Grandparents for their prayers, my aunts and my uncle. I also dedicate this dissertation to my many friends and colleagues who have supported me throughout the process. I will always appreciate all they have done, especially my closest friends Wassila Boudouaya, for helping me, Fatima Zahra Benarbia, Aisha Derouich, Fatima Bentahar and many other friends who kept supporting and encouraging me in everything for the many hours of proofreading. I Acknowledgements Today is the day that writing this note of thanks is the finishing touch on my dissertation. -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

The Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg ✵ ✵ the Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg ✵

The Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg ✵ ✵ The Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg ✵ TRH Grand Duke Henri and Grand Duchess Maria Teresa wave to the crowd from the balcony of the Grand Ducal Palace (7 October 2000) Historical introduction ✹07 Chapter One The House of Luxembourg-Nassau ✹17 - The origins of the national dynasty 18 - The sovereigns of the House of Luxembourg 20 - Grand Duke Adolphe 20 - Grand Duke William IV - Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde 21 - Grand Duchess Charlotte 22 - Grand Duke Jean 24 - Grand Duke Henri 28 Grand Duchess Maria Teresa 32 - Hereditary Grand Duke Guillaume 34 - Grand Duke Henri’s brothers and sisters 36 - HRH Grand Duke Henri’s accession to the throne on 7 October 2000 40 Chapter Two The monarchy today ✹49 - Prepared for reign 50 - The Grand Duke’s working day 54 - The Grand Duke’s visits abroad 62 - Visits by Heads of State to Luxembourg 74 - The public image of the Grand Ducal Family in Luxembourg 78 Chapter Three The constitutional monarchy ✹83 - The political situation of the Grand Duke 84 SUMMARY - The order of succession to the throne 92 Index - Index Accession to the Grand Ducal Throne 94 - The Lieutenancy 96 - The Regency 98 Chapter Four The symbols of the monarchy ✹101 - National Holiday – official celebration day of the Grand Duke’s birthday 102 - Coats of arms of the Grand Ducal House 104 - The anthem of the Grand Ducal House 106 Chapter Five The residences of the Grand Ducal Family ✹109 - The Grand Ducal Palace 110 - Berg Castle 116 - Fischbach Castle 118 Annexe - The Grand Duke’s visits abroad - Visits by Heads of State to Luxembourg HistoricalIntro introduction History Historical summary Around 963 1214 Siegfried acquires the rocky Ermesinde of Luxembourg outcrop of Lucilinburhuc marries Waleran of Limburg 1059-1086 1226- 1247 Conrad I, Count of Luxembourg Ermesinde, Countess of Luxembourg 8 1136 ✹ Death of Conrad II, last Count 1247-1281 Henry V of Luxembourg, of Luxembourg from the House known as Henry the Blond, of Ardenne. -

Ballet” for the Tsar of February 1672

Scando-Slavica 59:2 (2013) 145–184. Orpheus and Pickleherring in the Kremlin: !e “Ballet” for the Tsar of February 1672 Claudia Jensen and Ingrid Maier Claudia Jensen, Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Box 353580, University of Wash- ington, Sea!le, Washington USA; [email protected]. Ingrid Maier, Uppsala University, Dept. of Modern Languages, Box 636, S-751 26 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] Abstract !is article identi"es and describes a pivotal event in the formation of the Russian court theatre: a performance in February 1672 for the Russian royal family given by a small group of foreign residents in Moscow. !is performance (and another that followed in May) was the direct catalyst for the formation of Tsar Aleksej Michajlovič’s court theatre in October 1672. By examining a series of contemporary published accounts (printed newspapers and the 1680 work by Jacob Rautenfels) and unpublished diplomatic dispatches, we have not only been able to pinpoint the date for this event (16 February 1672), but also establish the important connections between Western theatrical practice and the beginnings of staged theatre in Russia. Because some of the characters (or their actions) featured in this "rst Western-style performance appeared later in Tsar Aleksej’s regular court theatre (especially the stock comic "gure Pickleherring), our work not only re- writes the pre-history of Russian theatre, but also contextualises the performances that followed. More broadly, the documents we use (some of which are newly discovered) show the importance to cultural historians of the communications revolution in Early Modern Europe, with its emphasis on the regular transmission of current news and information through newspapers and diplomatic dispatches, sources that have rarely been used for studies of early Russian culture.