Berkeley, a City in History"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Existing Conditions

2. EXISTING CONDITIONS This chapter provides a description of existing conditions within the City of Lafayette relevant to the Bikeways Master Plan. Information is based on site visits, existing planning documents, maps, and conversations with Lafayette residents and City of Lafayette, Contra Costa County and other agency staff. 2.1. SETTING The City of Lafayette is situated in a semi-rural valley in Contra Costa County, approximately twenty miles east of San Francisco, on the east side of the Oakland/Berkeley hills. Lafayette has a population of approximately 24,000, and encompasses about 15 square miles of land area, for a population density of about 1,500 persons per square mile. Settlement started in the late 1800s but incorporation did not occur until 1968. Lafayette developed its first general plan in 1974, and this general plan was last updated in 2002. The City is bordered on the north by Briones Regional Lafayette-Moraga Trail along St. Mary’s Park, on the east by Walnut Creek, on the south by Moraga and Road near Florence Drive the west by Orinda. Mixed in along its borders are small pockets of unincorporated Contra Costa County. Lafayette has varied terrain, with steep hills located to the north and south. Highway 24 runs through the City, San Francisco is a 25-minute BART ride away, and Oakland’s Rockridge district is just two BART stops away. LAFAYETTE LAND USES Lafayette’s existing development consists mostly of low- to medium-density single family residential, commercial, parkland and open space. Land uses reflect a somewhat older growth pattern: Commercial areas are located on both sides of Mt. -

University of California, Berkeley

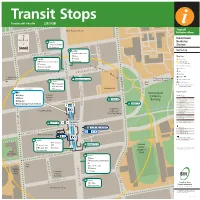

Transit Stops Paradas del tránsito 公車站地圖 Transit H E A R S T A V E To Gourmet Ghetto Information H E N R Y S T N Downtown W E Berkeley W S 18 Lake Merritt BART Station 0 100ft A FS San Francisco L N 0 30m Berkeley U 7 El Cerrito del Norte BART T 18 Albany S Map Key BERKELEY WAY T F UC Campus You Are Here SHATTUCK AVE 51B Berkeley Amtrak/Berkeley Marina FS Drop o only 5-Minute Walk 1000ft/305m Radius 52 UC Village 5 B2 Station Entrance/Exit 79 El Cerrito Plaza BART - M I N BART Train 800 Richmond BART U T E Bus UNIVERSITY AVE W Bus Stop A T O X F O R D S T Elevator To West Berkeley L H K To Memorial Stadium and 4th Street 52 UC Campus E Wheelchair Accessible and Greek Theater C Transit Information R West 51B Rockridge BART E Gate Bike Lane, Bike Boulevard, 79 Rockridge BART S S or Bike Friendly Street H University Hall C E Inside Station: 800 San Francisco A N T Transit Lines T T U University of Berkeley AC Transit Daly City C California, Repertory K Local Bus Lines Millbrae 6 Downtown Oakland Theatre 65 7 El Cerrito del Norte BART T A Berkeley Richmond N S 18 University Village, Albany I S O V A D D 18 Lake Merritt BART Warm Springs/South Fremont E 6 51B Berkeley Amtrak / Berkeley Marina B1 A1 51B Rockridge BART 52 University Village, Albany 52 UC Berkeley UC Berkeley 65 Lawrence Hall of Science 67 Spruce St & Grizzly Peak Blvd Freight & Salvage Art Museum / 79 El Cerrito Plaza BART 79 Rockridge BART Pacific Film Archive 88 Lake Merritt BART M All Nighter Bus Lines (Approx. -

Creeks of UC Berkeley

University of California, Berkeley 2 A TOUR OF THIS WALKING TOUR is a guide to Strawberry STRAWBERRY Creek on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley. Strawberry Creek is a CREEK ON major landscape feature of the campus, with THE UC its headwaters above the UC Botanical Garden BERKELEY in Strawberry Canyon. This tour covers only the central campus and should last about an CAMPUS hour. It begins at Faculty Glade, follows the South Fork downstream, and ends at Giannini Hall along the North Fork. A map with indicated stops is located at the end of this booklet. A BRIEF HISTORY In 1860, the College of California moved from Oakland to the present campus site, pur- chasing the land from Orrin Simmons, a sea captain turned farmer. Strawberry Creek was one of the main reasons the founders chose Simmons’ tract. “All the other striking advan- tages of this location could not make it a place fit to be chosen as the College Home without this water. With it every excellence is of double value.” The creek was named for the wild strawberries that once lined its banks. The central campus at that time was pastureland and grain fields. Coast live oaks, sycamores, bay laurel trees, and native shrubs lined the banks of Strawberry Creek. Three forks of the creek meandered through the cam- pus. In 1882, the small middle fork draining the central glade was filled to build a cinder running track, now occupied by the Life Sci- ences Building Addition. By the turn of the century, urbanization had already begun to affect the creek. -

Berkeley Marina Area Berkeley Pier/Ferry Facility

Berkeley Marina Area Specific Plan + Berkeley Pier/Ferry Facility Planning Study COUNCIL WORKSESSION February 16, 2021 Overview • Waterfront background and issues • Update on status of Pier/Ferry and BMASP projects • Discuss possible solutions and changes • Get City Council feedback History of Berkeley Marina COMMUNITY WORKSHOP #1 BERKELEY MARINA AREA specific plan 01/28/2021 page 3 Berkeley Marina History COMMUNITY WORKSHOP #1 BERKELEY MARINA AREA specific plan 01/28/2021 page 4 Existing Berkeley Marina COMMUNITY WORKSHOP #1 BERKELEY MARINA AREA specific plan 01/28/2021 page 5 Berkeley Waterfront Regulatory Agencies + Land Use Restrictions Land Use Restrictions • State Lands Commission – Tideland Grant Trust (1913) • BCDC - 100’ Shoreband Jurisdiction • BCDC – 199 Seawall Drive and Parking Lot – Fill Permit (1966) • City of Berkeley Measure L – Open Space Ordinance (1986) • Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Grants – (early 1980) Regulatory Agencies • Army Corp of Engineers • BCDC • California Department of Fish and Wildlife • State Regional Water Quality Control Board • State Lands Commission COMMUNITY WORKSHOP #1 BERKELEY MARINA AREA specific plan 01/28/2021 page 6 Economics of Berkeley Marina Area Operating Revenues* Operating Expenses Berth Rental Fees (55%) Marina Operations Hotel Lease (21%) Waterfront Maintenance Other Leases (14%) Marina Capital Projects Other Boating Fees (5%) Fund Lease Management Youth Programming (2%) Recreation Programs Other (2%) Internal Service Charges Water-Based Recreation (1%) Debt Service Security Special Events *Based on FY19 revenue COMMUNITY WORKSHOP #1 BERKELEY MARINA AREA specific plan 01/29/2021 page 7 Marina Fund Challenges Reserves depleted in FY2022 Annual Change in Reserve Balance End of Year Reserve Balance 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 COMMUNITY WORKSHOP #1 BERKELEY MARINA AREA specific plan 01/29/2021 page 8 Marina Fund Challenges • Marina Fund was never set up to succeed. -

IV.L. Transportation/Traffic

IV. Environmental Impact, Setting, and Mitigation Measures IV.L. Transportation/Traffic IV.L.1 Introduction This chapter evaluates project impacts on transportation facilities and existing transportation operating conditions in the vicinity of the project area, including neighborhood traffic, vehicular circulation, parking, transit and shuttle services, and pedestrian and bicycle circulation. IV.L.2 Setting LBNL is located close to three major highways: Interstate 80/5801 approximately three miles to the west, and State Routes (SR) 24 and 13, two miles to the south. Access from the Lab to I-80/580 is through the city of Berkeley via arterial roads. Access to SR 24 and SR 13 is via Tunnel Road. Grizzly Peak Boulevard, which runs through a largely undeveloped area, provides a minor local access route. Berkeley Lab is approximately one mile from the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station in downtown Berkeley. IV.L.2.1 Regional Roadways and Routes into Berkeley Regional freeway access to LBNL is provided by I-80/580, SR 24, and SR 13. These roadways are part of both the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) Metropolitan Transportation System (MTS) and the Alameda County Congestion Management Agency (ACCMA) Congestion Management Program (CMP) network (see Figure IV.L-1). The primary objective of designating a CMP system is to monitor performance in relation to established level of service standards (ACCMA, 1999a). The MTS network is generally consistent with, but not identical to, the CMP network, encompassing 22 miles of local streets in the city of Berkeley not in the CMP network. Interstate 80. I-80 connects the San Francisco Bay Area with the Sacramento region. -

Codornices Creek Watershed Restoration Action Plan

Codornices Creek Watershed Restoration Action Plan Prepared for the Urban Creeks Council By Kier Associates Fisheries and Watershed Professionals 207 Second Street, Ste. B Sausalito, CA 94965 November, 2003 The Codornices Creek watershed assessment and salmonid restoration planning project, the results of which are reported here, was funded by the Watershed Program of the California Bay-Delta Authority, through Contract No. 4600001722 between the California Department of Water Resources and the Urban Creeks Council. The Urban Creeks Council is a non-profit organization working to preserve, protect, and restore urban streams and their riparian habitat. The Urban Creeks Council may be reached at 1250 Addison Street, Ste. 107, Berkeley, CA 94702 (510- 540-6669). Table of Contents Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements...................................................................................................................... ii Introduction Fish and stream habitat records................................................................................................. 1 Other Codornices Creek studies................................................................................................ 1 Methods: How Each Element of the Project Was Undertaken Fish population assessment methods ........................................................................................ 2 Salmonid habitat assessment methods..................................................................................... -

Agenda Packet Is Available for Download at Weta.Sanfranciscobayferry.Com

Members of the Board SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA WATER EMERGENCY TRANSPORATION AUTHORITY James Wunderman, Chair BOARD OF DIRECTORS SPECIAL MEETING Jessica Alba Thursday, May 20, 2021 at 1:00 p.m. Jeffrey DelBono Anthony J. Intintoli, Jr. VIDEOCONFERENCE Monique Moyer Join WETA BOD Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89718217408 Meeting ID: 897 1821 7408 Password: 33779 Dial by your location +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) +1 929 205 6099 US (New York) The full agenda packet is available for download at weta.sanfranciscobayferry.com AGENDA 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ROLL CALL 3. APPROVE FY 2022-2024 TITLE VI PROGRAM Action 4. PRELIMINARY FISCAL YEAR 2021/22 OPERATING AND CAPITAL Information BUDGETS 5. WETA BUSINESS PLAN CONCEPT AND ORGANIZATION Information ADJOURNMENT All items appearing on the agenda are subject to action by the Board of Directors. Staff recommendations are subject to action and change by the Board of Directors. CHANGES RELATED TO COVID-19 Consistent with Governor Gavin Newsom’s Executive Orders N-25-20 and N-29-20, effective immediately and until further notice, meetings will be conducted through virtual participation to promote social distancing and reduce the chance of COVID-19 transmission. PUBLIC COMMENTS As this is a special meeting of the Board, public comments are limited to the listed agenda items. If you know in advance that you would like to make a public comment during the videoconference, please email [email protected] with your name and item number you would like to provide comment on no later than 15 Water Emergency Transportation Authority May 20, 2021 Meeting of the Board of Directors minutes after the start of the meeting. -

1947–48 General Catalog

GEE1IAL€AIIL OGUE Primarily. for Students in the DEPARTMENTS AT LOS ANGELES Fall and Spring Semesters 1947-1948 JUNE 1. 1947 For Solt by the U. C. L. A. Students' Store, Los Angeles PRICE , TWENTY-FIVE CENTS :University of California Bulletin PUBLISHED AT BERKELEY ,•' CALIFORNIA- volume XLI June I; 1947 Number I I A seriesin the administrativebulletins of the Universityof Califor- •nia. Entered July t, tgti , at the Post Ofce at Berkeley; California, as second-class matter under the Act of Congress of August *4, 19ta (which supersedes the Actof July t6, t8&,14). Issued semimonthly.. GENERAL INFORMATION Letters of inquiry concerning the University of California at Los Angel should ;be .addressedto the .Registrar, University of Cali- fornia, .fof Hilgard Avenue, Los Angeles s4, California. Letters of inquiry concerning the University in general should be addressed to tite ..tagiatrar, University.of California, Berkeley 4, California. For the list of bulletins of information concerning the several colleges and departments,see. pages 3 and 4 of the cover of this Catalogue. In writing for information please mention the c llege, depart- ment, or study in which you are chiefly interested. The registered cable address of the University of California at Los Angeles is ua.#. .•a AU announcementsherein are-subject to revision. Changes in the list of Oficers of Administration ,and Instruction ." be ittade sub- sequent to the publication of this . Announcement , June s, r947. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GENERALCATALOGUE Admission and Degree Requirements -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

TR-060, the East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California, October 1991* United States Fire Administration Technical Report Series

TR-060, The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California, October 1991* United States Fire Administration Technical Report Series The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California Federal Emergency Management Agency United States Fire Administration National Fire Data Center United States Fire Administration Fire Investigations Program The United States Fire Administration develops reports on selected major fires throughout the country. The fires usually involve multiple deaths or a large loss of property. But the primary criterion for deciding to do a report is whether it will result in significant "lessons learned." In some cases these lessons bring to light new knowledge about fire -the effect of building construction or contents, human behavior in fire, etc In other cases, the lessons are not new but are serious enough to highhght once again, with yet another fire tragedy report. The reports are Sent to fire magazines and are distributed at national and regional fire meetings. The International Association of Fire Chiefs assists USFA in disseminating the findings throughout the fire service.. On a continuing basis the reports are available on request from USFA; announcements of their availability are published widely in fire journals and newsletters This body of work provides detailed information on the nature of the fire problem for policymakers who must decide on allocations of resources between fire and other pressing problems, and within the fire service to improve codes and code enforcement, training, public tire education, building technology, and other related areas The Fire Administration, which has no regulatory authority, sends an cxperienced fire investigator into a community after a major incident only after having conferred with the local tire authorities to insure that USFA's assistance and presence would be supportive and would in no way interfere with any review of the incident they are themselves conducting. -

Press Release Below to Your Local Media

Please forward the press release below to your local media. Thank you. Press Release: USA Student Wins World Neuroscience Competition August, 2017; Washington, DC, USA Future neuroscientists from 25 countries around the world met in Washington, DC this week to compete in the nineteenth World Brain Bee Championship. The Brain Bee is a neuroscience competition for young students, 13 to 19 years of age. It was hosted by the American Psychological Association. The International Brain Bee President and Founder is Dr. Norbert Myslinski ([email protected]) of The University of Maryland Dental School, Department of Neural and Pain Sciences. Its purpose is to motivate young men and women to study the brain, and to inspire them to enter careers in the basic and clinical neurosciences. We need bright young men and women to help treat and find cures for the 1000 neurological and psychological disorders around the world. The Brain Bee "Builds Better Brains to Fight Brain Disorders.” The 2017 World Brain Bee Champion is Sojas Wagle, a sophomore from Har-Ber High School in Arkansas, USA. Legend: Sojas Wagle Sojas has a breath taking history of accomplishments. He is the captain of his school’s Quiz Bowl Team, and was state MVP for the last two years. He placed third in the National Geographic Bee in 2015. Last year, he was chosen for “Who Wants to be a Millionaire” Whiz Kids Edition. By the end of the game show, he had won $250,000, and later donated some of his winnings to his school district and a children’s hospital. -

Tidal Marsh Recovery Plan Habitat Creation Or Enhancement Project Within 5 Miles of OAK

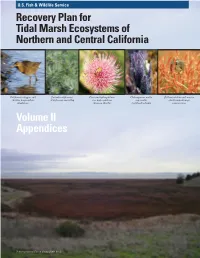

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California California clapper rail Suaeda californica Cirsium hydrophilum Chloropyron molle Salt marsh harvest mouse (Rallus longirostris (California sea-blite) var. hydrophilum ssp. molle (Reithrodontomys obsoletus) (Suisun thistle) (soft bird’s-beak) raviventris) Volume II Appendices Tidal marsh at China Camp State Park. VII. APPENDICES Appendix A Species referred to in this recovery plan……………....…………………….3 Appendix B Recovery Priority Ranking System for Endangered and Threatened Species..........................................................................................................11 Appendix C Species of Concern or Regional Conservation Significance in Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California….......................................13 Appendix D Agencies, organizations, and websites involved with tidal marsh Recovery.................................................................................................... 189 Appendix E Environmental contaminants in San Francisco Bay...................................193 Appendix F Population Persistence Modeling for Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California with Intial Application to California clapper rail …............................................................................209 Appendix G Glossary……………......................................................................………229 Appendix H Summary of Major Public Comments and Service