Jacqueline Wilson Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2014 UK Author Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacqueline Wilson Dream Journal Ebook Free Download

JACQUELINE WILSON DREAM JOURNAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jacqueline Wilson, Nick Sharratt | 240 pages | 03 Jul 2014 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780857534316 | English | London, United Kingdom Jacqueline Wilson Dream Journal PDF Book The three girls have been best friends forever, but now Ellie is convinced she's fat, Nadine wants to be a model, and Magda worries that her appearance is giving guys the wrong idea. Em adores her funny, glamorous dad - who cares if he's not her real father? The Diary of a Young Girl. Lily Alone. I Am Sasha. Have you ever wondered what happened to Tracy Beaker? All rights reserved. This was also the first of her books to be illustrated by Nick Sharratt. See More. Friend Reviews. For me, books like this have to exist so that novels covering the more unusual family or young lives of the time can actually be compared with something. Lucky for Mum, because now she's got the flu, so I've got to mind her - and help with all the babies! Isabella Torres rated it it was amazing Oct 27, Rent a Bridesmaid. Jacqueline Wilson Biscuit Barrel. Abschnitt 8. It was a fascinating book and portions of it made me laugh loudly. Log In. The Worry Website. You have no items in your shopping cart. My Secret Diary: Dating, Dancing, Dreams and Dilemmas Best-loved author Jacqueline Wilson continues the captivating story of her life with this gripping account of her teenage years — school life, first love, friends, family and everything! Beauty and her meek, sweet mother live in uneasy fear of his fierce rages, sparked whenever they break one of his fussy house rules. -

Dustbin Baby Free

FREE DUSTBIN BABY PDF Jacqueline Wilson,Nick Sharratt | 240 pages | 27 Mar 2007 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780552556118 | English | London, United Kingdom Dustbin Baby () directed by Juliet May • Reviews, film + cast • Letterboxd Dustbin Baby helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Dustbin Baby by Jacqueline Wilson. Dustbin Baby by Jacqueline Wilson. April Showers so called because of her birth date, April 1, and her tendency to burst into tears at the drop of a hat was unceremoniously dumped in a Dustbin Baby bin when she was only a few hours old. Her young life has passed by in a blur of ever-changing foster homes but Dustbin Baby she enters her teens she decides it is time to find out the truth about her real family. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published October 1st by Corgi Childrens first published September More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Dustbin Babyplease sign up. Did April find her mother? Navika This answer contains spoilers… view spoiler [No, she found Frankie and got a phone. Donya Do not think so but I Dustbin Baby read it to know Dustbin Baby happend in the real end. See all 4 questions about Dustbin Baby…. -

Most Borrowed Titles July 2005 – June 2006

MOST BORROWED TITLES JULY 2005 – JUNE 2006 Contents Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult & Children Combined) Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult) Most Borrowed Children’s Fiction Titles Most Borrowed Non-Fiction Titles (Adult) Most Borrowed Children’s Non-Fiction Titles Most Borrowed Classic Titles (Adult) Most Borrowed Classic Titles (Children) Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult & Children Combined) Author Title Publisher Year 1. Dan Brown The Da Vinci Code Corgi 2004 2. J K Rowling Harry Potter and the Half Blood Price Bloomsbury 2005 3. Maeve Binchy Nights of Rain and Stars Orion 2004 4. Dan Brown Digital Fortress Corgi 2004 5. Patricia Cornwell Trace Little, Brown 2004 6. James Patterson & Howard Roughan Honeymoon Headline 2005 7. James Patterson & Maxine Paetro 4th of July Headline 2005 8. John Grisham The Broker Century 2005 9. Josephine Cox The Journey HarperCollins 2005 10. Ian Rankin Fleshmarket Close Orion 2004 11. Josephine Cox Live the Dream HarperCollins 2004 12. James Patterson London Bridges Headline 2004 13. James Patterson Lifeguard Headline 2005 14. Dan Brown Angels and Demons Corgi 2003 15. Wilbur Smith Triumph of the Sun Macmillan 2005 16. Michael Connelly The Closers Orion 2005 17. James Patterson Mary, Mary Headline 2005 18. Jacqueline Wilson (illus Nick Sharratt) Clean Break Doubleday 2005 19. Kathy Reichs Cross Bones Heinemann 2005 20. Lee Child One Shot Bantam 2005 Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult) Author Title Publisher Year 1. Dan Brown The Da Vinci Code Corgi 2004 2. Maeve Binchy Nights of Rain and Stars Orion 2004 3. Dan Brown Digital Fortress Corgi 2004 4. Patricia Cornwell Trace Little, Brown 2004 5. -

National GROSSED-UP

100 MOST BORROWED BOOKS (JULY 2003 – JUNE 2004) National ISBN Title Contributor Publisher 1. 0747551006 Harry Potter and the order of J.K. Rowling Bloomsbury the phoenix Children's 2. 0712670599 The king of torts John Grisham Century 3. 0752851659 Quentin's Maeve B inchy Orion 4. 0007146051 Beachcomber Josephine Cox Harper Collins 5. 0747271550 Jinnie Josephine Cox Headline 6. 0747271569 Bad boy Jack Josephine Cox Headline 7. 0333761359 Blue horizon Wilbur Smith Macmillan 8. 0440862795 The story of Tracy Beaker Jacqueline Wilson: ill by Nick Yearling Sharratt 9. 0712684263 The summons John Grisham Century 10. 0752856561 Lost light Michael Connelly Orion 11. 0747271542 The woman who left Josephine Cox Headline 12. 0747263493 Four blind mice James Patterson Headline 13. 0434010367 Bare bones Kathy Reichs Heinema nn 14. 0571218210 The murder room P.D. James Faber 15. 1405001097 Fox evil Minette Walters Macmillan 16. 0593050088 Dating game Danielle Steel Bantam 17. 0007127170 Bad company Jack Higgins HarperCollins 18. 0007120109 Sharpe's havoc: Richard Bernard Cornwell HarperCollins Sharpe and the campaign in Northern> 19. 0752851101 A question of blood Ian Rankin Orion 20. 0593047087 Answered prayers Danielle Steel Bantam 21. 0747546290 Harry Potter and the prisoner J. K. Rowling Bloomsbury of Azkaban 22. 0552546534 Lizzie Zipmouth Jacqueline Wilson: ill Nick Sharratt Young Corgi 23. 0755300181 The jester James Patterson and Andrew Headline Gross 24. 0002261359 Emma's secret Barbara Taylor Bradford HarperCollins 25. 0440863023 Mum-minder Jacqueline Wilson: + ill Nick Yearling Sharratt 26. 0747271526 Looking back Josephine Cox Headline 27. 0747263507 2nd chance James Patterson with Andrew Headline Gross 28. 0752821415 Chasing the dime Michael Connelly Orion 29. -

Recent Issue-Driven Fiction for Young People

OOK WORLD B Boekwêreld • Ilizwe Leencwadi Recent issue-driven fi ction for young people Compiled by JOHANNA DE BEER Assistant Director: Selection and Acquisitions or an introduction to this list of realistic novels, written for older children and teenagers, that deal with issues that are there is, amazingly enough, somebody else out there who’s been Fexperienced by and of concern to this specifi c age group, I through exactly the same thing, it’s when you’re in your teenage turned to a very useful guide to teenage literature, The ultimate years. (Fiction can be hugely comforting for this, in a way that all teen book guide edited by Daniel Hahn and Leonie Flynn (Black, the self-help books in the world, for all their practical worthiness, 2006). This guide is a most useful resource for any teacher or simply cannot)… whatever your own experience it’s somehow librarian working with young people, and indeed young people enormously soothing to read a book that strikes a chord, that themselves, with annotations to over 700 titles suitable for makes you break off in the middle of a sentence and stare into the teenagers and suggestions for further reads if one has enjoyed a middle distance and nod and think: ‘Yes, that’s just how it feels’. specifi c title. Added extras include top ten lists culled from polling (p. 168.) teen readers themselves with the Harry Potter-series topping several Kevin Brooks is one author who does not shy away from the lists from the Book-that-changed-your-life to the Book-you-couldn’t grim reality and harsh challenges facing some young people. -

GARY PARKER Writer

GARY PARKER Writer 2021 OPAL MOONBABY TV adaptation of series of children’s books by Maudie Smith in development 2020-21 FLATMATES (SERIES 2) Lead writer and writer of 3 x episodes Produced by Zodiak for BBC 2020 EJ12 – GIRL HERO Pilot script in development with Ambience Entertainment 2019 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SPECIALS) Wrote 2 x special episodes Produced by Zodiak for CBBC 2017-18 MILLE INBETWEEN (SERIES 4) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 4 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2016 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 3) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 4 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2015 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 2) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 5 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2013-14 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 1) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 7 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2013 DANI’S CASTLE 2 episodes for RDF Television/Foundation TV 2012 JILLY COOPER ADAPTATION 100 minute TV film adaptation of a Jilly Cooper novel Cooperworld (Neil Zeiger / Greg Boardman) 2010-12 DANI’S HOUSE 7 episodes for RDF Television/Foundation TV 2011 CAMPUS Wrote Pilot and Series 1. Moniker Pictures/Channel 4 DELIVERANCE Team writing for 60 minute comedy drama and series for Company/Channel 4 BEN & HOLLY’S LITTLE KINGDOM 10 x 11 minute scripts for Elf Factory/Nick Jnr and Five Milkshake 2010 FREAKY FARLEYS 3 x 22 minute script for RDF Television/Foundation TV TATI’S HOTEL 2 x 11 minute script for Machine Productions 2009 MUDDLE EARTH 2 x 11 minute animated script for CBBC DANI’S HOUSE 3 x 22 minute script for RDF Television/Foundation TV MYTHS REWIRED 6 x 1 hour series in development with Lime Pictures MIRROR MIRROR 1 x 30 minute episode for BBC3 CAMPUS Pilot for Moniker Pictures Ltd/Channel 4 GASPARD ET LISA Two episodes for Chorion UK 2008 SCHOOL OF COMEDY Sketches for Series, Leftbank/Channel 4. -

Jacqueline Wilson Biography

Jacqueline Wilson Early life Jacqueline Aitken (she became Wilson when she got married) was born in the city of Bath, in England, on 17th December 1945. Jacqueline’s parents met at a dance in a famous old building in bath called the Pump Room. Her mother was doing office work for the navy and her father was a draughtsman. This was a job which involved drawing skilful plans of machinery and buildings. When Jacqueline was about three years old, her father changed jobs and took the family to live in Kingston upon Thames, near London. For a while they shared their house with Jacqueline’s grandparents who lived downstairs. Jacqueline and her mother and father soon moved to a council flat and Jacqueline started school in 1950. She had a difficult time at first because she fell ill with measles and whooping cough and had to have several months off school. School and Education When she was six she moved to a school called Latchmere Primary and soon settled in. Jacqueline loved English, Art, country dancing and listening to stories. When she was eight, Jacqueline’s mother brought her a very realistic toy dog as Jacqueline longed to have a pet. From the age of seven, Jacqueline loved making up her own stories. She copied out drawings into a blank notebook and invented stories to go with her pictures. When Jacqueline was eleven, she went to a brand new girls’ secondary school in New Malden called Coombe School. She passed her eleven plus and took English, Art and History at school. -

By Jacqueline Wilson. Katy Is a Book About a Girl Who Is the Oldest out of Her Six Siblings. Katy Loves Doing Dangerous St

Katy- by Jacqueline Wilson. Katy is a book about a girl who is the oldest out of her six siblings. Katy loves doing dangerous stuff such as: skateboarding, tree climbing and swinging as high as she can on the rope swing. One day a terrible accident happens, and this story is about her life. I think my friends would like this story because it's about a girl who is the same age as us about to start high school like we will be doing. She also goes through struggles like some 11 year olds would. I think Katy is a great book and would recommend it to my friends because it shows some struggles we will have to overcome during secondary school. It also shows you don't always have to have just one friend because soon Katy learns that she can have more friends than just Cecy Hall. I love this book! Bethany Wingate The Spy Who Loved School Dinners by Pamela Butchart When new girl Mathilde starts at school, Izzy and her friend soon realise something is not quite right. They tried to warn her about school dinners (aka poison) but she really loves them, and even has seconds. This is when they realise that Mathilde is a spy who has come to find out their secrets. They must stop her before it’s too late! This book is very exciting because it is full of adventure and surprise. I’ve tried to pick a favourite bit but I can’t because I loved all of it. -

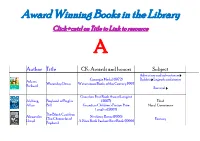

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Great Books for Year 6 Oct 2017

Have you tried……….? Lensey Namioka Ties that Bind, Ties that Break Mildred D Taylor Roll of Thunder, Hear my Cry Ian McEwan The Daydreamer Lord Deramore’s School presents Margaret Mahy The Haunting A selection of Ian Serraillier The Silver Sword Jan Mark Thunder and Lightnings Ursula le Guin A Wizard of Earthsea Great Books Philippa Pearce Tom’s Midnight Garden for Year 6 Zizou Corder Lion Boy + sequels Melvin Burgess The Ghost Behind the Wall Michael Morpurgo (Children’s Laureate 2003-2005) Betsy Byars The Eighteenth Emergency Billy the Kid Jeanne Willis Sticky Ends Friend or Foe Gill Lewis Sky Hawk (and several more…) The Wreck of the Zanzibar Roddy Doyle A Greyhound of a Girl Why the Whales Came John Boyne The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas The Dancing Bear Suzanne Lafleur Eight Keys Out of the Ashes Pittacus Lore The Lorien Legacies Private Peaceful Rebecca Stead Liar and Spy The Amazing Adolphus Tips Edward Carey The Ironmonger Trilogy Running Wild Tracey Corderoy Baddies, Beasties and a Sprinkling of Crumbs Shadow Monsters, Mayhem and a Sprinkling of Crumbs Little Manfred Jerry Spinelli Stargirl War Horse Anne Cassidy Killing Rachel Alone on a Wide, Wide Sea Stuart Hill Prince of the Ice Mark Medal for Leroy Carrie Jones Time Stoppers Pinocchio by Pinocchio Sarah Crossan Apple & Rain Listen to the Moon Lara Williamson The Boy Who Sailed the Ocean in an Armchair An Eagle in the Snow Robin Stevens Mistletoe & Murder Toto Ali Sparkes Car-jacked Tanya Landman The Poppy Fields mysteries (10 books) Tom Palmer Wings: Flyboy Kaye Umansky Hammy House of Horror Zana Fraillon The Bone Sparrow Clover Twig and the Incredible And not forgetting…. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Double Act by Jacqueline Wilson Double Act

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Double Act by Jacqueline Wilson Double Act. Growing up as twins has been brilliantly captured by Jacqueline Wilson. Full of poignancy and plenty of humour throughout- it’s a real feel-good book. Double Act Synopsis. Ruby and Garnet are ten-year-old twins. Identical. They do EVERYTHING together, especially since their mother died three years earlier. But can being a double act work for ever? When so much around them is changing… If you loved this, you might like these. All versions of this book. ISBN: 9780440866312 Publication date: 07/10/2004 Publisher: Random House Children's Books Format: Paperback. Book Information. ISBN: 9780440866312 Publication date: 7th October 2004 Author: Jacqueline Wilson Publisher: Random House Children's Books Format: Paperback Pagination: 96 pages Suitable for: 9+ readers Recommendations: eBooks. About Jacqueline Wilson. Jacqueline Wilson wrote her first novel when she was nine years old, and she has been writing ever since. She is now one of Britain’s bestselling and most beloved children’s authors. She has written over 100 books and is the creator of characters such as Tracy Beaker and Hetty Feather. More than forty million copies of her books have been sold. As well as winning many awards for her books, including the Children’s Book of the Year, Jacqueline is a former Children’s Laureate, and in 2008 she was appointed a Dame. Jacqueline is also . Double ACT. An adaptation of the popular novel by Jacqueline Wilson. The resources section provides lively ideas on how the play might be staged as well as background material for classroom study.