Rwandan Refugee Physical (In) Security in Uganda: Views from Below

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of Uganda (Ministry of Works And

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA (MINISTRY OF WORKS AND TRANSPORT COMPONENT) IDA CREDIT NO.4147 UG REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE EAST AFRICA TRADE AND TRANSPORT FACILITATION PROJECT (EATTFP) FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 2015 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2015 ...................................................................................................................... iv REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE SPECIAL ACCOUNT OPERATIONS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2015 ........................................................................................................... vi 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 3.0 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND COMPONENTS .......................................................................... 1 4.0 AUDIT OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. 2 5.0 AUDIT PROCEDURES PERFORMED ........................................................................................ 3 6.0 CATEGORIZATION AND SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................................................... 4 6.2 Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................... -

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

COVID-19 Interventions Report Financial Year 2019/20

COVID-19 Interventions Report Financial Year 2019/20 October 2020 Budget Monitoring and Accountability Unit (BMAU) Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Sector Performance .............................................................................................................. 2 2.1Agriculture Sector ............................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Education and Sports Sector ............................................................................................ 2 2.3 Health Sector .................................................................................................................... 7 2.3.1 Financial Performance................................................................................................... 7 2.3.2 Overall performance ...................................................................................................... 9 2.3.3 Detailed Performance by output for GoU Support........................................................ 9 2.3.4 Contingency Emergency Response Component (CERC) towards COVID-19 by the World Bank .......................................................................................................................... -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

The Informal Cross Border Trade Qualitative Baseline Study 2008 Uganda Bureau of Statistics

UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS THE INFORMAL CROSS BORDER TRADE QUALIT ATIVE BASELINE STUDY 2008 February 2009 FOREWORD The Qualitative Module of the Informal Cross Border Trade (ICBT) Survey is the first comprehensive Study of its kind to be conducted in Uganda to bridge information gaps regarding informal trade environment. The study was carried out at Busia, Mirama Hills, Mpondwe and Mutukula border posts. The ICBT Qualitative study collected information on informal trade environment and the constraints traders’ experience in order to guide policy formulation, planning and decision making in the informal cross border sub-sector. The study focused specifically on gender roles in ICBT, access to financial services, marketing information, food security, and tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade among others. This study was conducted alongside the ICBT Quantitative Module that collected information on the nature of products transacted, their volumes and value, and, the direction of trade. Notwithstanding the significant contribution informal cross border trade has made to the welfare of the people of the East African region (in terms of employment creation, economic empowerment of women, food security, regional and social integration), there are no appropriate policies designed to guide players in the informal trade sector. The information gathered, therefore, will provide an insight into the challenges informal traders face in their day to day business and will guide policy and decision makers to enact appropriate policies to harness the potential benefits of informal cross border trade. The Bureau is grateful to the Integrated Framework (IF) through TRACE Project of the Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Industry for the financial contribution that facilitated the study. -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll Free Line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @Urapage Twitter: @Urauganda

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll free line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @URApage Twitter: @URAuganda CENTRAL REGION ( Kampala, Wakiso, Entebbe, Mukono) s/n Station Location Tax Heads URA Head URA Tower , plot M 193/4 Nakawa Industrial Ara, 1 Domestic Taxes/Customs Office P.O. Box 7279, Kampala 2 Katwe Branch Finance Trust Bank, Plot No 115 & 121. Domestic Taxes 3 Bwaise Branch Diamond Trust Bank,Bombo Road Domestic Taxes 4 William Street Post Bank, Plot 68/70 Domestic Taxes Nakivubo 5 Diamond Trust Bank,Ham Shopping Domestic Taxes Branch United Bank of Africa- Aponye Hotel Building Plot 6 William Street Domestic Taxes 17 7 Kampala Road Diamond Trust Building opposite Cham Towers Domestic Taxes 8 Mukono Mukono T.C Domestic Taxes 9 Entebbe Entebbe Kitooro Domestic Taxes 10 Entebbe Entebbe Arrivals section, Airport Customs Nansana T.C, Katonda ya bigera House Block 203 11 Nansana Domestic Taxes Nansana Hoima road Plot 125; Next to new police station 12 Natete Domestic Taxes Natete Birus Mall Plot 1667; KyaliwajalaNamugongoKira Road - 13 Kyaliwajala Domestic Taxes Martyrs Mall. NORTHERN REGION ( East Nile and West Nile) s/n Station Location Tax Heads 1 Vurra Vurra (UG/DRC-Border) Customs 2 Pakwach Pakwach TC Customs 3 Goli Goli (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 4 Padea Padea (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 5 Lia Lia (UG/DRC - Border) Customs 6 Oraba Oraba (UG/S Sudan-Border) Customs 7 Afogi Afogi (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 8 Elegu Elegu (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 9 Madi-opei Kitgum S/Sudan - Border Customs 10 Kamdini Corner -

Uganda at 50: the Past, the Present and the Future

UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 ii A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue 2012 Published by ACODE P.O. Box 29836, Kampala - UGANDA Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Kabarungi, N. (2013). Uganda at 50: The Past, the Present and the Future. A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue. ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No.17, 2013. Kampala. © ACODE 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is exempted from this restriction. ISBN 978 9970 34 009 5 Cover Photo: A Cross section of participants attending the Uganda @50 in 4 Hours Dialogue held on October 3, 2012 at Sheraton Hotel in Kampala. -

Mogondo Julius Wondero EOEIYE

d/ TELEPHONES: 04L434OLO0l4340LL2 Minister of State for East E.MAIL: [email protected] African Community Affairs TELEFAX: o4t4-348r7t 1't Floor, Postal Building Yusuf Lule Road ln any correspondence on this subject P.O. Box 7343, Kampala please quote No: ADM 542/583/01 UGANDA rHE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 22"4 August,2Ol9 FTHES P ( L \-, 4 Hon. Oumo George Abott U Choirperson, Committee for 2019 * 2 3 AUG s Eost Africon Community Affoirs Porlioment of Ugondo EOEIYE L t4 raE \, \, KAMPATA NT OF CLOSURE OF UGANDA.RWANDA BORDERS Reference is mode to letter AB: I 171287 /01 doted l5rn August,20l9 oddressed to the Minister of Eost Africon Community Affoirs ond copied to the Permonent Secretory, Ministry of Eost Africon Community Affoirs regording the obove subject motter. ln the letter, you invited the Ministry to updote the EAC Committee on the progress mode to hondle the Closure of Ugondo-Rwondo Borders on Ihursdoy,29r,August, 2019 at 10.00om. As stoted this discussion would help ensure thot the Eost Africon Common Morket Protocol is effectively implemented for the benefit of Ugondo ond other Portner Stofes. The Purpose of this letter therefore, is to forword to you o Report on the Stotus of the obove issue for further guidonce during our interoction with the committee ond to re-offirm our ottendonce os per the stipuloted dote ond time Mogondo Julius Wondero MINISTER OF STATE FOR EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS C.C. The Speoker, Porlioment of Ugondo, Kompolo The Clerk to Porlioment, Porlioment of Ugondo, Kompolo Permonent Secretory, Ministry of Eost Africon Community Affoirs MINISTRY OF EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY AFFAIRS REPORT ON THE CLOSURE OF UGANDA. -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Cover photo taken by ISER. An elderly woman having her biometric and biographic details captured by Centenary Bank at a distribution point for the Senior Citizens’ Grant in Kayunga District. Consent was obtained to use this image in our report, advocacy, and associated communications material. Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. -

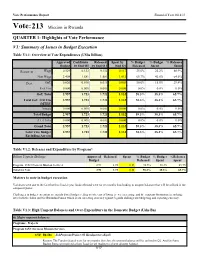

Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda QUARTER 1: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q1 by End Q 1 End Q1 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 0.529 0.132 0.132 0.117 25.0% 22.2% 88.9% Non Wage 2.408 1.581 1.581 1.012 65.7% 42.0% 64.0% Devt. GoU 0.020 0.010 0.010 0.003 50.0% 15.0% 29.4% Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total GoU+Ext Fin 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% (MTEF) Arrears 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Total Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% A.I.A Total 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Grand Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total Vote Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1652 Overseas Mission Services 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total for Vote 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Matters to note in budget execution Variances were due to the fact that this finacial year funds released were for six months thus leading to unspent balances that will be utilised in the subquent Quater. -

Presidential Intervention and the Changing 'Politics of Survival' in Kampala's Informal Economy

Tom Goodfellow and Kristof Titeca Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Goodfellow, Tom and Titeca, Kristof (2012) Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy. Cities, 29 (4). pp. 264-270. ISSN 0264-2751 DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.004 © 2012 Elsevier This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/39762 Available in LSE Research Online: May 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy Published in Cities: The International