279 1. Area Occupied by the .Rocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck, Rùm Report No: HAS051202 Client The Small Isles Community Council Date December 2005 Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles December 2005 Summary This report sets out general recommendations and specific proposals for the development of archaeology on and for the Small Isles of Canna, Eigg, Muck and Rùm. It reviews the islands’ history, archaeology and current management and visitor issues, and makes recommendations. Recommendations include ¾ Improved co-ordination and communication between the islands ¾ An organisational framework and a resident project officer ¾ Policies – research, establishing baseline information, assessment of significance, promotion and protection ¾ Audience development work ¾ Specific projects - a website; a guidebook; waymarked trails suitable for different interests and abilities; a combined museum and archive; and a pioneering GPS based interpretation system ¾ Enhanced use of Gaelic Initial proposals for implementation are included, and Access and Audience Development Plans are attached as appendices. The next stage will be to agree and implement follow-up projects Vision The vision for the archaeology of the Small Isles is of a valued resource providing sustainable and growing benefits to community cohesion, identity, education, and the economy, while avoiding unnecessary damage to the archaeological resource itself or other conservation interests. Acknowledgements The idea of a Development Plan for Archaeology arose from a meeting of the Isle of Eigg Historical Society in 2004. Its development was funded and supported by the Highland Council, Lochaber Enterprise, Historic Scotland, the National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage, and the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, and much help was also received from individual islanders and others. -

Download Trip Notes

Isle of Skye and The Small Isles - Scotland Trip Notes TRIP OVERVIEW Take part in a truly breathtaking expedition through some of the most stunning scenery in the British Isles; Scotland’s world-renowned Inner Hebrides. Basing ourselves around the Isles of Skye, Rum, Eigg and Muck and staying on board the 102-foot tall ship, the ‘Lady of Avenel’, this swimming adventure offers a unique opportunity to explore the dramatic landscapes of this picturesque corner of the world. From craggy mountain tops to spectacular volcanic features, this tour takes some of the most beautiful parts of this collection of islands, including the spectacular Cuillin Hills. Our trip sees us exploring the lochs, sounds, islands, coves and skerries of the Inner Hebrides, while also providing an opportunity to experience an abundance of local wildlife. This trip allows us to get to know the islands of the Inner Hebrides intimately, swimming in stunning lochs and enjoying wild coastal swims. We’ll journey to the islands on a more sustainable form of transport and enjoy freshly cooked meals in our downtime from our own onboard chef. From sunsets on the ships deck, to even trying your hand at crewing the Lady of Avenel, this truly is an epic expedition and an exciting opportunity for adventure swimming and sailing alike. WHO IS THIS TRIP FOR? This trip is made up largely of coastal, freshwater loch swimming, along with some crossings, including the crossing from Canna to Rum. Conditions will be challenging, yet extremely rewarding. Swimmers should have a sound understanding and experience of swimming in strong sea conditions and be capable of completing the average daily swim distance of around 4 km (split over a minimum of two swims) prior to the start of the trip. -

A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: an Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1992 A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Utz, Hans (1992) "A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 27: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hans UIZ A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture The book Voyage en Ecosse et aux Iles Hebrides by Louis-Albert Necker de Saussure of Geneva is the basis for my report.! While he was studying in Edinburgh he began his private "discovery of Scotland" by recalling the links existing between the foreign country and his own: on one side, the Calvinist church and mentality had been imported from Geneva, while on the other, the topographic alternation between high mountains and low hills invited comparison with Switzerland. Necker's interest in geology first incited his second step in discovery, the exploration of the Highlands and Islands. Presently his ethnological curiosity was aroused to investigate a people who had been isolated for many centuries and who, after the abortive Jacobite Re bellion of 1745-1746, were confronted with the advanced civilization of Lowland Scotland, and of dominant England. -

Shorewatch News

Issue 16: Summer 2014 ShorewatchShorewatch News What’s inside this issue? Big Watch Weekend.....page 2/3 Wild Dolphins..............page 3 Events & News............page 4 ©WDC/ Fiona Hill ©WDC/ Walter Innes Walter ©WDC/ Hello Shorewatchers, Summer has arrived and is going by very quickly, you have all been out doing lots of watches all around the coastline and we have really enjoyed receiving all your exciting data! Spey Bay has been a hive of activity, with many sightings of the bottlenose dolphins and lots of visitors through the door! The Wild Dolphins (featured above) have been a great hit in Aberdeen - lots of people taking part in the trail. We’ve recently had some great news about the Marine Protected Areas around the Scottish Coast, largely thank- ful to all the data we have been able to present to the Scottish Government, which has come from you. So thank you for all your efforts - keep up the good work! (turn to page 4 for more info) Happy watching! Sara Pearce Supported by: A world where every whale and dolphin is safe and free Shorewatch News Big Watch Weekend Issue 16: Summer 2014 June 2014: Your efforts and sightings David Haines: 12 Carol Breckenridge watches; minke, & Colin Graham: 10 Pippa Stevens, harbour porpoise, watches; 3 minke Gordon Newman, Marie 60 common dolphin Newman, Anne Milne, & 4 orca Gillian Steel, Sara Pearce, Wendy Else, Peter Jackie Pullinger, Ron Barclay, Prince: 12 watches; 2 Murray Aitken, Ann-Paulette harbour porpoise Coats, Lorraine Macdonald & Graham Kidd: Jacky Haynes: 13 watches; 3 31 watches; -

Ownership. Opportunities for Self-Н‐Build Housing Could Be Promoted

ownership. Opportunities for self-build housing could be promoted via sales of plots. • Agricultural potential is marginal and likely to remain so for some time, particularly with the uncertainties caused by Brexit. There is scope to assist in increasing the resident population of Ulva by creating multiple holdings with residents having a mix of income sources from agriculture/crofting and other employment. • There is potential for further woodland development but this will need to be decided in the context of other land uses on Ulva and the viability of additional plantings. • There is significant scope to increase visitor numbers to the island and promote the conservation of Ulva’s natural, cultural and built heritage through community-led projects, either independently or in partnership with other bodies. • There is a range of opportunities for business development. Ardalum House could be re-opened as a hostel. A campsite and bike hire business could be developed alongside the re-opened hostel. Ulva House could be let to a private business. The community could develop additional new-build small business spaces with a particular focus on tourism-related businesses. • NWMCWC is likely to have various development roles as community landlord following a successful buyout of Ulva. They will include direct delivery of projects, working in partnership with other organisations and enabling things to be done by others (for example, by providing housing plots and/or business space). • NWMCWC should consider management and governance arrangements for its role as community landlord of Ulva that maximise input from local residents and other interested organisations. For example, via continuation of the recently established Ulva Steering Group as a sub-committee of the NWMCWC with co-opted members from Ulva, Ulva Ferry and the wider North West Mull area, along with additional representation from other community groups as appropriate. -

Marion's Garden Development Concept

Of Interest. .... Scottish names & meanings throughout Marians Garden The names of streets and building projects throughout the Marians Garden project include some that are different from those many are used to seeing. We include a guide to pronunciation and meaning in this issue. Also in.eluded are some interesting facts about Scotland, the former home of Mike and Fiona Harrison, the Marians Garden developers .. Islay, pronounced "Eye-la", is the island which Mike and Fiona Harrison lived on in Scotland. There are two possibilities for the origination of the meaning of this word. Some say it means 1-lagh, the Law Island, ( I means island and laug means law) while others believe it means an island divided in two ( I means island, and l<=:ithe means half). Port Charlotte is a village on Islay and is known to be the best preserved and most attractive of those on Isla{ It is named for the viilage's founder, Walter Frederick Campbell's mother. Port Weyms, pronounced "Port Weems" means 'River Mouth'. It is a 19th century village near Port Na Haven on south west coast of Islay. Port Na Haven, built during the 19th century, about the same time as Port Weyms, means 'bay or harbor of the River'. Cao-ila, pronounced Col-ee-la, means 'the sound of Islay'. A small village on Islay and it is also the ~ nam~ of a.well known single malt whiskey distillery. Skerrols, was the name of Mike & Fiona's old farm house on Islay. The word's definition is 'fair pastures or tine land'. -

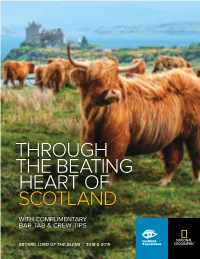

Through the Beating Heart of Scotland with Complimentary Bar Tab & Crew Tips

THROUGH THE BEATING HEART OF SCOTLAND WITH COMPLIMENTARY BAR TAB & CREW TIPS TM ABOARD LORD OF THE GLENS | 2018 & 2019 TM Lindblad Expeditions and National Geographic have joined forces to further inspire the world through expedition travel. Our collaboration in exploration, research, technology and conservation will provide extraordinary travel expe- riences and disseminate geographic knowledge around the globe. DEAR TRAVELER, The first time I boarded the 48-guest Lord of the Glens—the stately ship we’ve been sailing through Scotland since 2003—I was stunned. Frankly, I’d never been aboard a more welcoming and intimate ship that felt somehow to be a cross between a yacht and a private home. She’s extremely comfortable, with teak decks, polished wood interiors, fine contemporary regional cuisine, and exceptional personal service. And she is unique—able to traverse the Caledonian Canal, which connects the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via a passageway of lochs and canals, and also sail to the great islands of the Inner Hebrides. This allows us to offer something few others can—an in-depth, nine-day journey through the heart of Scotland, one that encompasses the soul of its highlands and islands. You’ll take in Loch Ness and other Scottish lakes, the storied battlefield of Culloden where Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising came to a disastrous end, and beautiful Glenfinnan. You’ll pass through the intricate series of locks known as Neptune’s Staircase, explore the historic Isle of Iona, and the isles of Mull, Eigg, and Skye, and see the 4,000-year-old burial chambers and standing stones of Clava Cairns. -

From the Low Tide of the Sea to the Highest Mountain Tops Community Ownership of the Isle of Eigg Amanda Bryan: Chair IEHT Eigg

From the low tide of the sea to the highest mountain tops Community ownership of the Isle of Eigg Amanda Bryan: Chair IEHT Eigg Located off the West coast of Scotland Part of the Small Isles Size: 9km by 5km (31km2) Accessible by ferry from Mallaig 5 days a week in winter 6 days a week in summer (weather permitting) Services Primary School Secondary School (Mallaig) GP (Sleat, Skye) History 432:50 1997 56% The Buyout: 12th June 1997 Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust IEHT (IERA, SWT, HC) Company Secretary Eigg Eigg Trading Eigg Electric Eigg Tearoom Construction Achievements: IEHT An Laimhrig (Hub) o Shop o Tearoom o Craft Shop o Toilets/ Showers o IEHT Office Achievements: IEHT Housing: o Secure affordable tenancies o Refurbished Trust housing o Housing Policy: Affordable plots for self build o Sales: e.g. Lodge Achievements: IEHT Land Management: o Crofting: Created 4 new crofts o Restructured 3 Farms o Infrastructure improvements: Fencing, Dyking, Paths o Forest Management (250Ha) o Environmental improvements: Peatland, Native woodlands Achievements: IEHT Island Wide Electrification Scheme o Island Grid (11km cable) o 3 Hydro Schemes (1 * 100kW, 2 * 6kW) o 4 Wind Turbines (4 * 6kW) o PV (50kW) o Diesel Back Up o Energy Control Measures (5kW/ house, 10kW/ business) o Battery Storage Achievements: Partnerships o New Pier & Ferry: Highland Council & CalMac o GP Surgery: NHS Highland o Broadband: Hebnet o Volunteering: SNH & SWT o Eigg Lodge: Earth Connections o Community Hall: Eigg Community Association EU Support LEADER RDP Structural Funds -

The Ferryman Presentation

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The Ferryman and Gaelic Recordings Jura Archives 1-6-2010 The Ferryman Presentation Gary McKay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/miscellaneous Recommended Citation McKay, Gary, "The Ferryman Presentation" (2010). The Ferryman and Gaelic Recordings. 8. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/miscellaneous/8 This the ferryman is brought to you for free and open access by the Jura Archives at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ferryman and Gaelic Recordings by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ferrymen A photographic documentary Gary McKay The Ferrymen A photographic documentary Gary McKay Feolin e -Press First e-published in Scotland in 2005 by Feolin Centre, Isle of Jura, Argyll, Scotland, UK PA60 7XX www.theisleofjura.co.uk Copyright ©Gary McKay, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher. The right of Gary McKay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 of Great Britain. All text and photographs and design © Gary McKay. Design, typeset and layout by G. McKay. Contents Introduction Southwest winds -

Download Brochure (PDF)

SCOTLAND HIGHLANDS & ISLANDS THROUGH THE HEART OF THE COUNTRY VIA THE CALEDONIAN CANAL WITH COMPLIMENTARY BAR TAB & CREW TIPS 2020 & 2021 VOYAGES | EXPEDITIONS.COM DEAR TRAVELER, The first time I boarded the 48-guest Lord of the Glens—the stately ship we’ve been sailing through Scotland since 2003—I was stunned. Frankly, I’d never been aboard a more welcoming and intimate ship that felt somehow to be a cross between a yacht and a private home. She’s extremely comfortable, with teak decks, polished wood interiors, fine contemporary regional cuisine, and exceptional personal service. And she is unique—able to traverse the Caledonian Canal, which connects the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via a passageway of lochs and canals, and also sail to the great islands of the Inner Hebrides. This allows us to offer something few others can—an in-depth journey through the heart of Scotland, one that encompasses the soul of its highlands and islands. You’ll take in Loch Ness and other Scottish lakes, the storied battlefield of Culloden where Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising came to a disastrous end, and beautiful Glenfinnan. You’ll pass through the intricate series of locks known as Neptune’s Staircase, explore the historic Isle of Iona, and the isles of Mull, Eigg, and Skye, and see the 4,000-year-old burial chambers and standing stones of Clava Cairns. There’s even time for a visit to the most remote pub in the British Isles. Scotland is a land of grand castles, beautiful moorlands, sacred abbeys, and sweeping mountains and you’ll have the opportunity to experience it all as few get to. -

Isle of Mull and Small Isles Explorer

ISLE OF MULL AND SMALL ISLES EXPLORER Enjoy an extraordinary voyage of seven nights exploring the Sound of Mull and the Small Isles. The Isle of Mull, inhabited since 6000 BC, is the quintessential island of the Inner Hebrides and rich in Scottish history. The outlying Small isles, Muck, Eigg, Rum and Canna, are justly famous for their sheltered anchorages, spectacular birdlife and ever-changing, island scenery. History, wildlife, spectacular islands and breathtaking mountains, this is a truly unforgettable Scottish cruise. Don't forget your hiking boots for stunning island walks! ITINERARY Days 1 - 7 Isle of Mull and Small Isles Some of the places we may visit are: Oban: Your departure point will be Oban (Dunstaffnage Marina), the gateway to the Hebridean isles. After a short introduction to life on board our small ship we depart for our first destination. Loch Aline: In the picturesque Loch Aline there are woodland walks and, at the head of the loch, is ancient Ardtornish estate and woodland gardens. Loch Drumbuie: A squeeze between high sided cliffs and we are in a perfectly sheltered anchorage. A lovely location for going sea kayaking or for a swim. Canna, the Small Isles: Canna is possibly the most beautiful of all the Small islands. Its 200 metre high cliffs of Compass Hill rise dramatically out of the sea and we have a good chance of seeing both sea and golden eagles. The anchorage on Canna is one of the best of the Small Isles and a stroll ashore to see the puffins and wild flower meadows of Sanday's Machair is a pure delight. -

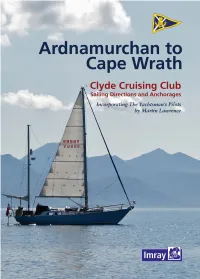

Ardnamurchan to Cape Wrath

N MOD Range Danger Area p.94 Cape Wrath p.94 8. Northwest Mainland Point of Stoer to Cape Wrath 30’ p.134 Kinlochbervie Loch p.93 Eriboll Depths in Metres Loch Inchard 0 10 20 30 p.93 Handa Is p.91 Loch Laxford Nautical Miles p.92 Eddrachilles Bay p.86 Kylesku p.89 LEWIS Point of Stoer p.75 s e id Enard Bay p.83 r b Lochinver p.84 e Ru Coigeach p.75 H r The North Minch e t 58˚N u Summer Isles p.80 O Ullapool p.79 HARRIS Rubha Reidh p.75 6. Sound of Raasay Loch Broom p.78 and approaches p.106 Loch Ewe p.77 Eilean 7. Northwest Mainland Trodday p.35 Loch Gairloch p.70 Rubha Reidh to Point 10 The Little Minch of Stoer Staffin p.59 Badachro p.71 p.118 Loch Snizort 2 Uig p.39 5 N UIST . p.38 p Loch Torridon p.67 Rona d p.57 n u 5. The Inner Sound 30’ o S p.87 r Off Neist e Poll Creadha p.65 Dunvegan p.37 n Point TSS n Portree I 10 Raasay Neist Point p.55 p.54 Loch Carron p.60 pp.29, 35 Skye Plockton p.60 Loch Bracadale p.33 Kyle of Lochalsh p.51 Loch Scalpay p.53 S UIST Harport p.34 Loch Duich p.49 Loch Scavaig p.32 Kyle Rhea 3. West Coast p.47 Sound of Sleat p.40 of Skye Loch Hourn p.43 p.53 Soay p.33 10 4.