Animal Ethics at the End of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Farm" Is the Story of a Farm Where the Animals Expelled Their

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/32376 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Vugts, Berrie Title: The case against animal rights : a literary intervention Issue Date: 2015-03-18 Introduction The last four decades have shown an especially intense and thorough academic reflection on the relation between man and animal. This is evidenced by the rapid growth of journals on the question of the animal within the fields of the humanities and social sciences worldwide.1 Yet also outside the academy animals now seem to preoccupy the popular mindset more than ever before. In 2002, the Netherlands was the first country in the world where a political party was established (the so-called “Partij voor de Dieren” or PvdD: Party for the Animals) that focused predominantly on animal issues. Heated discussions about factory-farming, the related spread of diseases (BSE/Q Fever), hunting and fishing practices, the inbreeding of domestic animals, are now commonplace. Animals, as we tend to call a large range of incredibly diverse creatures, come to us in many different ways. We encounter them as our pets and on our plates, animation movies dominate the charts and artists in sometimes rather experimental genres engage in the question of the animal.2 Globally speaking, animals might be considered key players in the climate debate insofar as the alarming rate of extinction of certain species is often taken to be indicative of our feeble efforts at preserving what is commonly referred to as “nature.” At the same time, these rates serve, albeit indirectly, as a grim reminder of the possible end of human existence itself. -

Philosophical Ethology: on the Extents of What It Is to Be a Pig

Society & Animals 19 (2011) 83-101 brill.nl/soan Philosophical Ethology: On the Extents of What It Is to Be a Pig Jes Harfeld Aarhus University, Denmark [email protected] Abstract Answers to the question, “What is a farm animal?” often revolve around genetics, physical attri- butes, and the animals’ functions in agricultural production. The essential and defining charac- teristics of farm animals transcend these limited models, however, and require an answer that avoids reductionism and encompasses a de-atomizing point of view. Such an answer should promote recognition of animals as beings with extensive mental and social capabilities that out- line the extent of each individual animal’s existence and—at the same time—define the animals as parts of wholes that in themselves are more than the sum of their parts and have ethological as well as ethical relevance. To accomplish this, the concepts of both anthropomorphism and sociobiology will be examined, and the article will show how the possibility of understanding animals and their characteristics deeply affects both ethology and philosophy; that is, it has an important influence on our descriptive knowledge of animals, the concept of what animal wel- fare is and can be, and any normative ethics that follow such knowledge. Keywords animal ethics, animal welfare, ethology, philosophy, sociobiology Preface The historical and theoretical background for this article is an ongoing debate in the interdisciplinary fields of biology and philosophy. On the one hand, the ideas presented in this article originate in the descriptive biological sciences— for example, classic and cognitive ethology, genetic evolutionary theory, and sociobiology. -

Cephalopods and the Evolution of the Mind

Cephalopods and the Evolution of the Mind Peter Godfrey-Smith The Graduate Center City University of New York Pacific Conservation Biology 19 (2013): 4-9. In thinking about the nature of the mind and its evolutionary history, cephalopods – especially octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid – have a special importance. These animals are an independent experiment in the evolution of large and complex nervous systems – in the biological machinery of the mind. They evolved this machinery on a historical lineage distant from our own. Where their minds differ from ours, they show us another way of being a sentient organism. Where we are similar, this is due to the convergence of distinct evolutionary paths. I introduced the topic just now as 'the mind.' This is a contentious term to use. What is it to have a mind? One option is that we are looking for something close to what humans have –– something like reflective and conscious thought. This sets a high bar for having a mind. Another possible view is that whenever organisms adapt to their circumstances in real time by adjusting their behavior, taking in information and acting in response to it, there is some degree of mentality or intelligence there. To say this sets a low bar. It is best not to set bars in either place. Roughly speaking, we are dealing with a matter of degree, though 'degree' is not quite the right term either. The evolution of a mind is the acquisition of a tool-kit for the control of behavior. The tool-kit includes some kind of perception, though different animals have very different ways of taking in information from the world. -

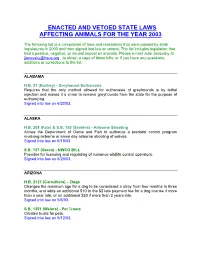

Enacted and Vetoed State Laws Affecting Animals for the Year 2003

ENACTED AND VETOED STATE LAWS AFFECTING ANIMALS FOR THE YEAR 2003 The following list is a compilation of laws and resolutions that were passed by state legislatures in 2003 and then signed into law or vetoed. The list includes legislation that had a positive, negative, or neutral impact on animals. Please e-mail Julie Janovsky at [email protected] , to obtain a copy of these bills, or if you have any questions, additions or corrections to the list. ALABAMA H.B. 37 (Buskey) - Greyhound Euthanasia Requires that the only method allowed for euthanasia of greyhounds is by lethal injection and makes it a crime to remove greyhounds from the state for the purpose of euthanizing. Signed into law on 6/20/03. ALASKA H.B. 208 (Fate) & S.B. 155 (Seekins) - Airborne Shooting Allows the Department of Game and Fish to authorize a predator control program involving airborne or same day airborne shooting of wolves. Signed into law on 6/18/03 S.B. 147 (Green) - NWCO BILL Provides for licensing and regulating of nuisance wildlife control operators. Signed into law on 6/28/03. ARIZONA H.B. 2121 (Carruthers) - Dogs Changes the minimum age for a dog to be considered a stray from four months to three months, and adds an additional $10 to the $2 late payment fee for a dog license if more than a year late, or an additional $20 if more than 2 years late. Signed into law on 5/6/03. S.B. 1351 (Weiers) - Pet Trusts Creates trusts for pets. Signed into law on 5/12/03. -

Animal Welfare and the Paradox of Animal Consciousness

ARTICLE IN PRESS Animal Welfare and the Paradox of Animal Consciousness Marian Dawkins1 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 1Corresponding author: e-mail address: [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Animal Consciousness: The Heart of the Paradox 2 2.1 Behaviorism Applies to Other People Too 5 3. Human Emotions and Animals Emotions 7 3.1 Physiological Indicators of Emotion 7 3.2 Behavioral Components of Emotion 8 3.2.1 Vacuum Behavior 10 3.2.2 Rebound 10 3.2.3 “Abnormal” Behavior 10 3.2.4 The Animal’s Point of View 11 3.2.5 Cognitive Bias 15 3.2.6 Expressions of the Emotions 15 3.3 The Third Component of Emotion: Consciousness 16 4. Definitions of Animal Welfare 24 5. Conclusions 26 References 27 1. INTRODUCTION Consciousness has always been both central to and a stumbling block for animal welfare. On the one hand, the belief that nonhuman animals suffer and feel pain is what draws many people to want to study animal welfare in the first place. Animal welfare is seen as fundamentally different from plant “welfare” or the welfare of works of art precisely because of the widely held belief that animals have feelings and experience emotions in ways that plants or inanimate objectsdhowever valuableddo not (Midgley, 1983; Regan, 1984; Rollin, 1989; Singer, 1975). On the other hand, consciousness is also the most elusive and difficult to study of any biological phenomenon (Blackmore, 2012; Koch, 2004). Even with our own human consciousness, we are still baffled as to how Advances in the Study of Behavior, Volume 47 ISSN 0065-3454 © 2014 Elsevier Inc. -

Wild Animal Suffering and Vegan Outreach

Paez, Eze (2016) Wild animal suffering and vegan outreach. Animal Sentience 7(11) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1101 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Sentience 2016.087: Paez Commentary on Ng on Animal Suffering Wild animal suffering and vegan outreach Commentary on Ng on Animal Suffering Eze Paez Department of Legal, Moral and Political Philosophy Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona Abstract: Ng’s strategic proposal seems to downplay the potential benefits of advocacy for wild animals and omit what may be the most effective strategy to reduce the harms farmed animals suffer: vegan outreach. Eze Paez, lecturer in moral and political philosophy at Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, studies normative and applied ethics, especially ontological and normative aspects of abortion and the moral consideration of nonhuman animals. He is a member of Animal Ethics. upf.academia.edu/ezepaez Underestimating the importance of wild animal suffering. Ng’s (2016) view is not that animal advocates should focus only on farmed animals, to the exclusion of those that live in the wild. He concedes that our efforts must also be directed toward raising awareness of the harms suffered by animals in nature. Nonetheless, he seems to suggest that these efforts should be minimal relative to those devoted to reducing the harms farmed animals suffer. Ng underestimates the potential benefits of advocacy for wild animals in terms of net reduction in suffering perhaps because he is overestimating people’s resistance to caring about wild animals and to intervening in nature on their behalf. -

The Ethics of the Meat Paradox

The Ethics of the Meat Paradox Lars Ursin* The meat paradox—to like eating meat, but dislike killing and harming animals—confronts omnivores with a powerful contradiction between eating and caring for animals. The paradox, however, trades on a conflation of the illegitimacy of harming and killing animals. While harming animals is morally wrong, killing animals can be legitimate if done with minimal suffering and respect for the moral status of the animal. This moral status demands the ac- knowledgement of a certain justification for killing animals that makes modesty a virtue of the omnivore. The psychological problem with regard to killing animals can persist even if the moral tension is weakened, but only to a certain degree, since emotions and principles are interdependent in moral reasoning. Virtuous meat consumption demands a willingness to face the conflicting feelings involved in killing animals and to tolerate the resulting tension. INTRODUCTION Humans and animals interact in a number of ways and establish a diversity of relationships. Humans relate to animals as members of the family, as research objects in the laboratory, as guide dogs, trained animals in sports and shows, and still many other kinds of relations. In some of these relations, animals are edible beings. The relation between humans and animals that are eaten is a special one. Like animals sacrificed for research purposes, the animals we eat are killed by us. The acceptance and legitimacy of this killing is thus an essential part of eating animals. By eating animals, we enter into a very intimate relation with the animal. We eat parts of the animal and digest the parts, thus allowing these parts to be absorbed into our bodies. -

Atrocities Go Vegan, Lose Weight MFA Undercover Investigation Exposes Heartbreaking Abuse Tips from an Expert the Artivists Creativity Meets Compassion

- FREE - Go ahead, take it. Living Compassionate CTHE MAG OF MFA. FALL-WINTERL 12 ISSUE 11 Wicked Walmart The Hidden Cost of the Mega Retailer's Cheap Pork Butterball Gets Busted Historic Cruelty Conviction + Auction Against Turkey Tyrant Atrocities Go Vegan, Lose Weight MFA Undercover Investigation Exposes Heartbreaking Abuse Tips from an Expert The Artivists Creativity Meets Compassion MercyForAnimals.org dear friends newswatch Living Meaty Environmental Issues The Scientific Veterinary Committee of the European Commission studied the matter extensively. What they Compassionate According to NPR, meat consumption in the reports that the 10 million automobiles in the region found wasn’t all too surprising: “When sows are put United States is on a downward spiral, and not only produce far less smog than the area's 300,000 into a very small pen, they indicate by their behavioral out of animal cruelty concerns. The media magnate dairy cows. responses that they find the confinement aversive. If given CL states that 29 percent of its Truven Health Analytics Water depletion is another major concern. Researchers the opportunity, they leave the confined space and they Health Poll’s 3,000 participants cited concern for the at the Stockholm International Water Institute find that usually resist attempts to make them return to that place.” Contributors environment as their motivation for forgoing animal "there will not be enough water available on current products. It’s no wonder why, considering the Amy Bradley croplands to produce food for the expected 9 billion frightening facts. In other words, pigs want freedom. Just like you and Becca Frye population in 2050 if we follow current trends and me. -

Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge

1 Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge Reservation Joseph Stromberg Senior Honors Thesis Environmental Studies and Anthropology Washington University in St. Louis 2 Abstract Land is invested with tremendous historical and cultural significance for the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Widespread alienation from direct land use among tribal members also makes land a key element in exploring the roots of present-day problems—over two thirds of the reservation’s agricultural income goes to non-Natives, while the majority of households live below the poverty line. In order to understand how current patterns in land use are linked with federal policy and tribal culture, this study draws on three sources: (1) archival research on tribal history, especially in terms of territory loss, political transformation, ethnic division, economic coercion, and land use; (2) an account of contemporary problems on the reservation, with an analysis of current land policy and use pattern; and (3) primary qualitative ethnographic research conducted on the reservation with tribal members. Findings indicate that federal land policies act to effectively block direct land use. Tribal members have responded to policy in ways relative to the expression of cultural values, and the intent of policy has been undermined by a failure to fully understand the cultural context of the reservation. The discussion interprets land use through the themes of policy obstacles, forced incorporation into the world-system, and resistance via cultural sovereignty over land use decisions. Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the Buder Center for American Indian Studies of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work as well as the Environmental Studies Program, for support in conducting research. -

Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm

[Expositions 6.1 (2012) 29–40] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 Unnaturally Cruel: Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm CHRISTIAN DIEHM University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point In 2010, over nine billion animals were killed in the United States for human consumption. This included nearly 1 million calves, 2.5 million sheep and lambs, 34 million cattle, 110 million hogs, 242 million turkeys, and well over 8.7 billion chickens (USDA 2011a; 2011b). Though hundreds of slaughterhouses actively contributed to these totals, more than half of the cattle just mentioned were killed at just fourteen plants. A slightly greater percentage of hogs was killed at only twelve (USDA 2011a). Chickens were processed in a total of three hundred and ten federally inspected facilities (USDA 2011b), which means that if every facility operated at the same capacity, each would have slaughtered over fifty-three birds per minute (nearly one per second) in every minute of every day, adding up to more than twenty-eight million apiece over the course of twelve months.1 Incredible as these figures may seem, 2010 was an average year for agricultural animals. Indeed, for nearly a decade now the total number of birds and mammals killed annually in the US has come in at or above the nine billion mark, and such enormous totals are possible only by virtue of the existence of an equally enormous network of industrialized agricultural suppliers. These high-volume farming operations – dubbed “factory farms” by the general public, or “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)” by state and federal agencies – are defined by the ways in which they restrict animals’ movements and behaviors, locate more and more bodies in less and less space, and increasingly mechanize many aspects of traditional husbandry. -

MAC1 Abstracts – Oral Presentations

Oral Presentation Abstracts OP001 Rights, Interests and Moral Standing: a critical examination of dialogue between Regan and Frey. Rebekah Humphreys Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom This paper aims to assess R. G. Frey’s analysis of Leonard Nelson’s argument (that links interests to rights). Frey argues that claims that animals have rights or interests have not been established. Frey’s contentions that animals have not been shown to have rights nor interests will be discussed in turn, but the main focus will be on Frey’s claim that animals have not been shown to have interests. One way Frey analyses this latter claim is by considering H. J. McCloskey’s denial of the claim and Tom Regan’s criticism of this denial. While Frey’s position on animal interests does not depend on McCloskey’s views, he believes that a consideration of McCloskey’s views will reveal that Nelson’s argument (linking interests to rights) has not been established as sound. My discussion (of Frey’s scrutiny of Nelson’s argument) will centre only on the dialogue between Regan and Frey in respect of McCloskey’s argument. OP002 Can Special Relations Ground the Privileged Moral Status of Humans Over Animals? Robert Jones California State University, Chico, United States Much contemporary philosophical work regarding the moral considerability of nonhuman animals involves the search for some set of characteristics or properties that nonhuman animals possess sufficient for their robust membership in the sphere of things morally considerable. The most common strategy has been to identify some set of properties intrinsic to the animals themselves. -

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition*

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition* Members of the Panel on Euthanasia Steven Leary, DVM, DACLAM (Chair); Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, High Ridge, Missouri Wendy Underwood, DVM (Vice Chair); Indianapolis, Indiana Raymond Anthony, PhD (Ethicist); University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska Samuel Cartner, DVM, MPH, PhD, DACLAM (Lead, Laboratory Animals Working Group); University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama Temple Grandin, PhD (Lead, Physical Methods Working Group); Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado Cheryl Greenacre, DVM, DABVP (Lead, Avian Working Group); University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee Sharon Gwaltney-Brant, DVM, PhD, DABVT, DABT (Lead, Noninhaled Agents Working Group); Veterinary Information Network, Mahomet, Illinois Mary Ann McCrackin, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACLAM (Lead, Companion Animals Working Group); University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Robert Meyer, DVM, DACVAA (Lead, Inhaled Agents Working Group); Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi David Miller, DVM, PhD, DACZM, DACAW (Lead, Reptiles, Zoo and Wildlife Working Group); Loveland, Colorado Jan Shearer, DVM, MS, DACAW (Lead, Animals Farmed for Food and Fiber Working Group); Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Tracy Turner, DVM, MS, DACVS, DACVSMR (Lead, Equine Working Group); Turner Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery, Stillwater, Minnesota Roy Yanong, VMD (Lead, Aquatics Working Group); University of Florida, Ruskin, Florida AVMA Staff Consultants Cia L. Johnson, DVM, MS, MSc; Director,