Dionysian Rock”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The Doors”—The Doors (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Richie Unterberger (Guest Post)*

“The Doors”—The Doors (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Richie Unterberger (guest post)* Original album cover Original label The Doors One of the most explosive debut albums in history, “The Doors” boasted an unprecedented fusion of rock with blues, jazz, and classical music. With their hypnotic blend of Ray Manzarek’s eerie organ, Robby Krieger’s flamenco-flecked guitar runs, and John Densmore’s cool jazz-driven drumming, the band were among the foremost pioneers of California psychedelia. Jim Morrison’s brooding, haunting vocals injected a new strand of literate poetry into rock music, exploring both the majestic highs and the darkest corners of the human experience. The Byrds, Bob Dylan, and other folk-rockers were already bringing more sophisticated lyrics into rock when the Doors formed in Los Angeles in the summer of 1965. Unlike those slightly earlier innovators, however, the Doors were not electrified folkies. Indeed, their backgrounds were so diverse, it’s a miracle they came together in the first place. Chicago native Manzarek, already in his late 20s, was schooled in jazz and blues. Native Angelenos Krieger and Densmore, barely in their 20s, when the band started to generate a local following, had more open ears to jazz and blues than most fledgling rock musicians. The charismatic Morrison, who’d met Manzarek when the pair were studying film at the University of California at Los Angeles, had no professional musical experience. He had a frighteningly resonant voice, however, and his voracious reading of beat literature informed the poetry he’d soon put to music. -

THE LORE of the DOORS: Celebrating Santa Barbara Connections As Legendary Rockers Mark Milestone

Newspress.com http://www.newspress.com/Top/Article/printArticle.jsp?ID... THE LORE OF THE DOORS: Celebrating Santa Barbara connections as legendary rockers mark milestone KARNA HUGHES, NEWS-PRESS STAFF WRITER February 11, 2007 8:18 AM Some say The Doors' late singer Jim Morrison wrote "The Crystal Ship" when he was dropping acid on an Isla Vista beach one night, transfixed by the glittering lights of Platform Holly, an offshore oil rig. Whispered rumors, legends and contrary accounts go hand in hand with iconic rock bands, and Santa Barbarans aren't immune to the mystique of The Doors. But though recirculated stories often stretch the bounds of credibility, the Los Angeles band does have some curious connections to Santa Barbara County. When The Doors receive a lifetime achievement Grammy Award tonight, some locals can even claim they knew the boys back in the beginning. In tribute to the band's 40th anniversary, being celebrated this year, we collected local trivia related to the group. Maybe you'll find yourself a few degrees from The Doors. • Before becoming The Doors' ace guitarist, Robby Krieger (then Robert Alan Krieger) was a student at UCSB, where he studied psychology from 1964 to 1965. He taught flamenco guitar to kids and practiced his grooves in the laundry room of his dorm. "It was a total party school," Mr. Krieger recalled in "The Doors by The Doors" (Hyperion, 2006). "There was a band of hippies at UCSB. Longhairs few and far between at that point. We were doing acid and stuff, but there weren't a lot (of) us, maybe twenty people that were hip, you know." 1 of 6 02/13/2007 1:34 PM Newspress.com http://www.newspress.com/Top/Article/printArticle.jsp?ID.. -

Hitmakers-1990-08-03

1-1 J ISSUE 649 fi(lG(1ST 3, 1990 55.00 an exclusive interview with L _ FOGELa President/CBS SHOW Industries I': 7d -. ~me co C+J 1M s-.0 1111, .. ^^-. f r 1 1 s rl Ji _ imp ii _U1115'11S The first hit single from the forthcoming album ALWAYS. Produced by L.A. Reid and Babyface for Laface, Inc. Management: Guilin Morey Associates .MCA RECORDS t 7990 MCA R,ords. S CUTTING EDGE LEADERSHIP FOR TODAY'S MUSIC RADIO Mainstream Top40 - Crossover Top40 - Rock - Alternative - Clubs/Imports - Retail ALDEN TO HEAD ELEKTRA PROMOTION Rick Alden has been National Marketing Manager, he was named Vice extremely good to me over the years, and I'm excited promoted to Senior Vice President of Top40 Promotion in November of 1987. about channeling my energies into this expanded President of Promotion Before joining ELEKTRA, Alden held positions at position. I'm working with the greatest staff, and we for ELEKTRA Entertain- ATLANTIC Records and RCA Records. are all looking forward to the future." ment, it was announced "After seeing the extraordinary results Rick has Also announced at ELEKTRA, by Vice President of this week by ELEKTRA achieved with Top40 Promotion, it became Urban Marketing and Promotion Doug Daniel, was Senior Vice Presi- increasingly clear that he was the man to head the appointment of Keir Worthy as National Director dent/General Manager Promotion overall," commented Hunt. "Rick's of Rap Promotion and Marketing. Brad Hunt. Alden was approach combines the analytic and the imaginative - Worthy previously served as Southwest/Midwest i previously Senior Vice he sees the big picture and never loses sight of the (See ALDEN page 40) RICK ALDEN President of Top40 details." Promotion, a post he Alden called his promotion "an honor and a was appointed to earlier this year. -

Ebook ~ the Very Best of the Doors: Piano/Vocal/Guitar # Read

JSRQWWJYTO > The Very Best of the Doors: Piano/Vocal/Guitar ~ PDF Th e V ery Best of th e Doors: Piano/V ocal/Guitar By Doors Alfred Publishing Co., Inc., United States, 2015. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 300 x 229 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. One of rock s most influential and controversial acts, The Doors embodied the countercultural spirit of the 60s and early 70s. Ray Manzarek s memorable keyboard lines and Jim Morrison s poetic lyrics helped make the group one of the best-selling bands of all time. This comprehensive collection contains piano transcriptions, vocal melodies, lyrics, and guitar chord diagrams. Titles: Back Door Man * Break on Through (To the Other Side) * The Changeling * The Crystal Ship * End of the Night * The End * Five to One * Ghost Song * Gloria * Hello, I Love You * L.A. Woman * Light My Fire * Love Her Madly * Love Me Two Times * Love Street * Moonlight Drive * My Eyes Have Seen You * Not to Touch the Earth * Peace Frog * People Are Strange * Riders on the Storm * Roadhouse Blues * Soul Kitchen * Spanish Caravan * Strange Days * Tell All the People * Touch Me * Twentieth Century Fox * The Unknown Soldier * Waiting for the Sun *... READ ONLINE [ 3.38 MB ] Reviews This ebook may be worth getting. I actually have read through and i am sure that i am going to likely to read through again once more down the road. You will not sense monotony at whenever you want of your respective time (that's what catalogues are for relating to should you check with me). -- Mr. -

L.A. WOMAN As Recorded by the Doors (From the 1971 Album L.A

L.A. WOMAN As recorded by The Doors (From the 1971 Album L.A. WOMAN) Transcribed by A Bit Of Finger Words and Music by The Doors A Intro Moderately Fast = 174 N.C.(A5) P 5x 1 g g I g 4 V V V V V V V V Gtr I V V V V V V V V T A 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 B 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 ggg R j I aP U fU W V W T V A 5 7 5 4 B 5 7 (7) H 8 ggg R j I aP U fU W V W T V A 5 7 5 4 B 5 7 (7) H U U W V P ggg z fV U I Gtr II 9 7 5 5 3 (3) T A B sl. sl. 12 g g I g j V V V fV V V V fV V V V W V V fV V T V A 7 7 7 5 7 (7) 7 5 7 7 7 (7) 7 7 5 7 B 7 ggg k P fV V V V V P V U k P V V V V V I z u z z V 2 3 2 3 2 u T 5 5 7 (7) 2 3 2 3 2 2 A 4 B sl. sl. sl. P Generated using the Power Tab Editor by Brad Larsen. http://powertab.guitarnetwork.org PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com L.A. -

Lord Jim Mythos of a Rock Icon Table of Contents

Lord Jim Mythos of a Rock Icon Table of Contents Prologue: So What? pp. 4-6 1) Lord Jim: Prelude pp. 7-8 2) Some Preliminary Definitions pp. 9-10 3) Lord Jim/The Beginning of the Morrison Myth pp. 11-16 4) Morrison as Media Manipulator/Mythmaker pp. 17-21 5) The Morrison Story pp. 18-24 6) The Morrison Mythos pp. 25-26 7) The Mythic Concert pp. 27-29 8) Jim Morrison’s Oedipal Complex pp. 30-36 9) The Rock Star as World Savior pp. 37-39 10) Morrison and Elvis: Rock ‘n’ Roll Mythology pp. 40-44 11) Trickster, Clown (Bozo), and Holy Fool pp. 45-50 12) The Lords of Rock and Euhemerism pp. 51-53 13) The Function of Myth in a Desacralized World: Eliade and Campbell pp. 54- 55 14) This is the End, Beautiful Friend pp. 56-60 15) Appendix A: The Gospel According to James D. Morrison pp. 61-64 15) Appendix B: Remember When We Were in Africa?/ pp. 65-71 The L.A. Woman Phenomenon 16) Appendix C: Paper Proposal pp. 72-73 Prologue: So What? Unfortunately, though I knew this would happen, it seems to me necessary to begin with a few words on why you should take the following seriously at all. An academic paper on rock and roll mythology? Aren’t rock stars all young delinquents, little more evolved than cavemen, who damage many an ear drum as they get paid buckets of money, dying after a few years of this from drug overdoses? What could a serious scholar ever possibly find useful or interesting here? Well, to some extent the stereotype holds true, just as most if not all stereotypes have a grain of truth to them; yet it is my studied belief that usually the rock artists who make the big time are sincere, intelligent, talented, and have a social conscience. -

Steve Waksman [email protected]

Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2010)v1i1.9en Live Recollections: Uses of the Past in U.S. Concert Life Steve Waksman [email protected] Smith College Abstract As an institution, the concert has long been one of the central mechanisms through which a sense of musical history is constructed and conveyed to a contemporary listening audience. Examining concert programs and critical reviews, this paper will briefly survey U.S. concert life at three distinct moments: in the 1840s, when a conflict arose between virtuoso performance and an emerging classical canon; in the 1910s through 1930s, when early jazz concerts referenced the past to highlight the music’s progress over time; and in the late twentieth century, when rock festivals sought to reclaim a sense of liveness in an increasingly mediatized cultural landscape. keywords: concerts, canons, jazz, rock, virtuosity, history. 1 During the nineteenth century, a conflict arose regarding whether concert repertories should dwell more on the presentation of works from the past, or should concentrate on works of a more contemporary character. The notion that works of the past rather than the present should be the focus of concert life gained hold only gradually over the course of the nineteenth century; as it did, concerts in Europe and the U.S. assumed a more curatorial function, acting almost as a living museum of musical artifacts. While this emphasis on the musical past took hold most sharply in the sphere of “high” or classical music, it has become increasingly common in the popular sphere as well, although whether it fulfills the same function in each realm of musical life remains an open question. -

„Break on Through to the Other Side“: the Symbols of Creation and Resurrection/Salvation in Jim Morrison. Theological Explorations1

TESTIMONIA THEOLOGICA XI, 2 (2017): 136-148 FEVTH.UNIBA.SK/VEDA/E-ZINE-TESTIMONIA-THEOLOGICA/ „BREAK ON THROUGH TO THE OTHER SIDE“: THE SYMBOLS OF CREATION AND RESURRECTION/SALVATION IN JIM MORRISON. THEOLOGICAL EXPLORATIONS1 Mgr. Pavol Bargár, M.St., Th.D. _________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: Although scholarship in many disciplines has paid much attention to the life and work of the American poet and vocalist of the band „The Doors“, Jim Morrison (1943- 1971), virtually no contributions to this topic have been made from a theological perspective. The submitted paper will seek to fill this lacuna at least to some extent. It explores the symbols of creation and resurrection/salvation as they appear in some of Morrison’s poems and lyrics. The paper will aim to argue that even though these symbols can have different meanings in Morrison and Christianity, respectively – and the latter ought to be in no way overlooked, much less leveled out – for Christian theology it is most helpful and refreshing to also engage in dialog with authors and ideas which are apparently non-Christian or even anti-Christian. Keywords: Symbol, Jim Morrison (1943-1971), Imagination, Theology and culture, Creativity 1. Introduction Even more than four decades after his untimely death, Jim Morrison (1943-1971), lead singer of the band The Doors, continues to be one of the most influential characters in the history of rock music, attracting the worldwide attention of people across cultures and age groups. However, it would be a mistake to view Morrison as a musician only as he also left a significant mark as a poet. -

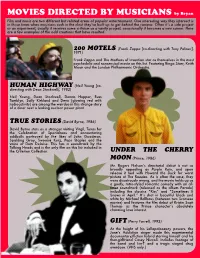

DIRECTED by MUSICIANS by Bryan Film and Music Are Two Different but Related Areas of Popular Entertainment

MOVIES DIRECTED BY MUSICIANS by Bryan Film and music are two different but related areas of popular entertainment. One interesting way they intersect is in those times when musicians cash in the clout theyʼve built up to get behind the camera. Often itʼs a side project or an experiment, usually it receives some criticism as a vanity project, occasionally it becomes a new career. Here are a few examples of the odd creations that have resulted. 200 MOTELS (Frank Zappa [co-directing with Tony Palmer], 1971) Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention star as themselves in the most psychedelic and nonsensical movie on this list. Featuring Ringo Starr, Keith Moon and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. HUMAN HIGHWAY (Neil Young [co- directing with Dean Stockwell], 1982) Neil Young, Dean Stockwell, Dennis Hopper, Russ Tamblyn, Sally Kirkland and Devo (glowing red with radioactivity) are among the weirdos in this strange story of a diner next a leaking nuclear power plant. TRUE STORIES (David Byrne, 1986) David Byrne stars as a stranger visiting Virgil, Texas for the Celebration of Specialness and encountering oddballs portrayed by the likes of John Goodman, Spalding Gray, Swoosie Kurz, Pops Staples and the voice of Dom DeLuise. This has a soundtrack by the Talking Heads and is the only film on this list included in the Criterion Collection. UNDER THE CHERRY MOON (Prince, 1986) Mr. Rogers Nelsonʼs directorial debut is not as broadly appealing as Purple Rain, and upon release it tied with Howard the Duck for worst picture at The Razzies. As is often the case, they were disastrously wrong, and the movie holds up as a goofy, retro-styled romantic comedy with an all- timer soundtrack (released as the album Parade) including the classics “Kiss” and “Sometimes It Snows in April.” Itʼs shot in beautiful black and white by Michael Ballhaus (between two Scorsese movies) and features the film debut of Kristin Scott Thomas as the Prince characterʼs absolutely charming love interest. -

Printable One Sheet

wild child Dave Brock’s Doors Experience former vocalist for Manzarek-Krieger of the doors Website – www.wildchild.info A Wild Child performance is the Email address – [email protected] closest thing to a real 1960’s Doors Facebook - Dave Brock - Los Angeles Entertainer concert and Live Doors Experience. This is not a typical tribute band. Wild Child relies on recapturing the original: sound, feel, mood, dynamics and delivery of the Doors music. In true Doors fashion there are no: wigs, props, costumes, or phony banter between song. It’s about the music and its delivery by top pro musicians and performers. This compact touring group has minimal technical requirements to make a big show. Fly in engagements are a snap. This four piece group has ove r two decades of world tour experience and always delivers! From 2010 to 2013, Wild Child lead singer Dave Brock fronted the touring act “Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger of The Doors.” Being selected by these two Rock’n Roll Hall of Fame musicians was a huge honor for Dave. This was the ultimate compliment of his talents and speaks volumes for his credibility as a doors style front man and vocalist. Here are a few things the media had to say about Wild Child. Radio Legend Jim Ladd said “These guys are excellent, not a cartoon version of The Doors” The L.A. Times said “Wild Child a winner! What’s amazing is that Brock sings like Morrison, enough to imperil the snowflake analogy about no two sets of vocal chords being able to produce the exact same tone.” The L.A. -

Didion, Joan the White Album

Didion, Joan The White Album Didion, Joan, (2009) "The White Album" from Didion, Joan, The White Album pp. 11 -48, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux © Staff and students of Strathclyde University are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: * access and download a copy; * print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by Strathclyde University. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author.