5B76cb5ada10c-1319518-Sample.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

A Nnual R Epo Rt 2002

CMYK Annual ReportAnnual 2002 - 2003 Annual Report 2002-2003 Department of Women and Child Development Women Department of Ministry Development of HumanResource Government ofIndia Government Department of Women and Child Development Ministry of Human Resource Development Government of India CMYK CMYK To call woman the weaker sex is a libel; it is mans injustice to woman. If by strength is meant brute strength, then, indeed, is woman less brute than man. If by strength is meant moral power, then woman is immeasurably mans superior. Has she not greater intuition, is she not more self-sacrificing, has she not greater powers of endurance, has she not greater courage? Without her man could not be. If nonviolence is the law of our being, the future is with woman. Who can make a more effective appeal to the heart than woman? Mahatma Gandhi Designed and produced by: Fountainhead Solutions (Pvt.) Ltd email: [email protected] CMYK Annual Report 2002-03 Department of Women and Child Development Ministry of Human Resource Development Government of India Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 An Overview 7 Chapter 3 Organization 17 Chapter 4 Policy and Planning 25 Chapter 5 The Girl Child in India 43 Chapter 6 Programmes for Women 73 Chapter 7 Programmes for Children 91 Chapter 8 Food and Nutrition Board 111 Chapter 9 Other Programmes 117 Chapter 10 Gender Budget Initiative 127 Chapter 11 Child Budget 143 Chapter 12 National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 153 Chapter 13 Central Social Welfare Board 163 Chapter 14 National Commission for Women 173 Chapter 15 Rashtriya Mahila Kosh 183 Annexures 189 Introduction O Lord, why have you not given woman the right to conquer her destiny? Why does she have to wait head bowed By the roadside, waiting with tired patience Hoping for a miracle in the morrow Rabindranath Tagore Introduction The Department of Women and Child Development was set up in 1985 as a part of the Ministry of Human Resource Development to give the much-needed impetus to the holistic development of women and children. -

DIRLIST6 01050000 01300000.Pdf

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01050011 KALRA SUNITA U74899DL1967PTC004762 R K INTERNATIOONAL PRIVATE 01050016 GUPTA VIVEK U51109OR2006PTC009068 MAHAKASH RENEWABLES (INDIA) 01050022 BHANDARI PARAMBIR SINGH U51909DL1999PTC100363 AKILA OVERSEAS PRIVATE LIMITED 01050036 BHUPENDRA GUPTA U70100MH1995PTC086049 SUNDER BUILDERS AND 01050064 KIRITKUMAR MERCHANT SHISHIR U51900MH2000PTC127408 HANS D TO R SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 01050071 AGARWAL BINDU U45201WB1997PTC084989 PRINCE SAGAR KUTIR PRIVATE 01050072 BIJOY HARIPRIYA JAIN U70109MH2008PTC180213 SAAT RASTA PROPERTIES PRIVATE 01050072 BIJOY HARIPRIYA JAIN U01403MH2008PTC182992 GREEN VALLEY AGRICULTURE 01050082 JAI KARUNADEVI PRITHVIRAJ U36993KA1999PTC025485 RODEO DRIVE LUXURY PRODUCTS 01050126 DEEPCHAND JAIN PRITHVIRAJ U36993KA1999PTC025485 RODEO DRIVE LUXURY PRODUCTS 01050174 JOGINDER SANDHU SINGH U67120CH2004PTC027291 JAGUAR CONSULTANTS PRIVATE 01050220 NARAYANAMURTHY U15421TN2006PLC060417 BHIMAAS SUGARS AND CHEMICALS 01050224 JITENDRA MEHTA U51109TN2007PTC062423 MOOLRAJ VYAPAR PRIVATE 01050251 PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA U72300DL2007PTC160451 PRODIGII ECALL PRIVATE LIMITED 01050251 PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA U63040DL2008PTC180031 REACHING WILD LIFE TOURISM 01050257 LALITKUMAR MERCHANT URMIL U51900MH2000PTC127408 HANS D TO R SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 01050273 KUSUM MISHRA U29248UP1999PTC024344 MAXWELL GEARS PRIVATE LIMITED 01050286 DUGGAL PRINCE U70109DL2006PTC153384 M R BUILDWELL PRIVATE LIMITED 01050290 JAI MISHRA SHANKAR U29248UP1999PTC024344 MAXWELL GEARS PRIVATE LIMITED 01050309 JAIN MUKESH U00000DL1992PTC050812 -

Understanding Meaningful Cinema

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Understanding Meaningful Cinema Dr. Debarati Dhar Assistant Professor, Vivekananda School of Journalism and Mass Communication Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, New Delhi. Received: June 23 , 2018 Accepted: August 03, 2018 Introduction: Cinephilia Cineastes say that films help the audience to reflect on the divergent cultures and justify the presence of multi-cultural, multi-ethnic audience in view of this divergence. The language of cinema continues to evolve in a living tradition and the filmmakers trace the ever-changing language of this medium from the silent era to the talkies, from the days when screen went from black and white and got colorized. Emotional appeal, subtlety in its communication and most importantly throwing a new light on the world, as we know it counted a lot to the audience. Filmmakers now work across the spectrum of media including painting, novels, theatre and opera. In the global cinema, in general, the production has become more accessible today, the qualitative aspects have sadly given way to quantity and so, films often miss emotional and spiritual richness. The world is a closer place today. Perhaps it is cinema that helps to blur the boundaries. The concept of film as a commercial art form started in fifties. The fifties and sixties are generally known as the golden period of Indian cinema not only because masterpieces were being made, but because of the popularity of the songs of that era. One of the distinctive features of Indian cinema is its narrative structure. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Ashoke Kumar

Ashoke Kumar The boss's wife and leading actress of a leading Film Company runs off with her lead man. She is caught and taken back but not the lead man who is unceremoniously dismissed. So now the company needs a new hero. The boss decides his laboratory assistant would be the Film Company's next leading man. A bizzare film plot??? Hardly. This real life story starred the Bombay Talkies Film Company, it's boss Himansu Rai , lead actress Devika Rani and lead man Najam-ul-Hussain and last but not least its laboratory assistant Ashok Kumar. And thus began an extremely successful acting career that lasted six decades! Ashok Kumar aka Dadamoni was born Kumudlal Kunjilal Ganguly in Bhagalpur and grew up in Khandwa. He briefly studied law in Calcutta, then joined his future brother-in-law Shashadhar Mukherjee at Bombay Talkies as laboratory assistant before being made its leading man. Ashok Kumar made his debut opposite Devika Rani in Jeevan Naiya (1936) but became a well known face with Achut Kanya (1936) . Devika Rani and he did a string of films together - Izzat (1937) , Savitri (1937) , Nirmala (1938) among others but she was the bigger star and chief attraction in all those films. It was with his trio of hits opposite Leela Chitnis - Kangan (1939) , Bandhan (1940) and Jhoola (1941) that Ashok Kumar really came into his own. Going with the trend he sang his own songs and some of them like Main Ban ki Chidiya , Chal Chal re Naujawaan and Na Jaane Kidhar Aaj Meri Nao Chali Re were extremely popular! Ashok Kumar initiated a more natural style of acting compared to the prevaling style that followed theatrical trends. -

Ek Paheli 1971 Mp3 Songs Free Download Ek Nai Paheli

ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download Ek Nai Paheli. Ek Nai Paheli is a Hindi album released on 10 Feb 2009. This album is composed by Laxmikant - Pyarelal. Ek Nai Paheli Album has 8 songs sung by Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas. Listen to all songs in high quality & download Ek Nai Paheli songs on Gaana.com. Related Tags - Ek Nai Paheli, Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli Songs Download, Download Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Listen Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli MP3 Songs, Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas Songs. Ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download. "Sunny Leones Ek Paheli Leela Makes Over Rs 15 Cr in Opening Weekend - NDTV Movies. The Indian box office is still reeling from Furious 7's blockbuster earnings of over Rs 80 . Jay Bhanushali: Really happy that people are enjoying 'Ek Paheli Leela' It's Sunny side up: Ek Paheli Leela touches Rs 10.5 crore in two days. More news for Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Ek Paheli Leela - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller film, written and directed by Bobby Khan and . The full audio album was released on 10 March 2015. Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie | NOORD . 1 day ago - Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie; Ek Paheli Leela; 2015 film; 4.8/10·IMDb; Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller . Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Online Watch Bollywood Full . onlinemoviesgold.com/ek-paheli-leela-full-movie-online-watch- bollywo. -

Akshay Kumar

Akshay Kumar Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mis- sion: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accu- rate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medi- cal, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Akshay Kumar 1 List of awards and nominations received by Akshay Kumar 8 Saugandh 13 Dancer (1991 film) 14 Mr Bond 15 Khiladi 16 Deedar (1992 film) 19 Ashaant 20 Dil Ki Baazi 21 Kayda Kanoon 22 Waqt Hamara Hai 23 Sainik 24 Elaan (1994 film) 25 Yeh Dillagi 26 Jai Kishen 29 Mohra 30 Main Khiladi Tu Anari 34 Ikke Pe Ikka 36 Amanaat 37 Suhaag (1994 film) 38 Nazar Ke Samne 40 Zakhmi Dil (1994 film) 41 Zaalim 42 Hum Hain Bemisaal 43 Paandav 44 Maidan-E-Jung 45 Sabse Bada Khiladi 46 Tu Chor Main Sipahi 48 Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi 49 Sapoot 51 Lahu Ke Do Rang (1997 film) 52 Insaaf (film) 53 Daava 55 Tarazu 57 Mr. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Once Upon a Time …

- Ô RUWANTHI ABEYAKOON Happy Valentine’s Day to all those who are celebrating it out there! This week many events will take place with Valentine’s Day in heart. Amid the many celebrations you can also enjoy the art exhibitions, dramas and musical recitals that take place within this week. Read the ‘Cultural Diary’ and know where to head to break away from the busy work schedule. You can also go for the thrilling movies that are screened at well known venues. If there is an event you would like others to know, drop an email to [email protected] or call us on 011 2429652. FEBRUARY show Alex wants many viewers to free their thoughts, invent connections and discover present day myths. None FEBRUARY Once Upon is wrong as none is correct. ‘Is he dead?’ They are all a part of the meaning to be shared. Imagine find- 27 ing in an old suitcase, a collection of drawings and paintings, ‘Is He Dead?’ presented by Elizabeth Moir School will take stage at the there are angels, three wheelers, forms that are based on betel Lionel Wendt, 18, Guildford Crescent, Colombo 7 on February 18 and 19. Barefoot 18 cutters, jungle and ruins. All familiar, but no words beyond enig- Gallery a time Lionel matic titles, you are left to decipher the image for yourselves. Wendt The illustrations of unwritten tales of an unwritten history- These new paintings also reflect something of Alex’s deepen- `Once upon a time’ by Alex Stewart will take place at Barefoot ing recollections of travelling in Sri Lanka over the last 15 years Gallery, 704, Galle road, Colombo 3, until February 27. -

Kishore Booklet Copy

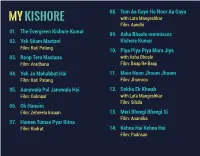

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31. -

Satya 13 Ram Gopal Varma, 1998

THE CINEMA OF INDIA EDITED BY LALITHA GOPALAN • WALLFLOWER PRESS LO NOON. NEW YORK First published in Great Britain in 2009 by WallflowerPress 6 Market Place, London WlW 8AF Copyright © Lalitha Gopalan 2009 The moral right of Lalitha Gopalan to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transported in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owners and the above publisher of this book A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-905674-92-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-905674-93-0 (hardback) Printed in India by Imprint Digital the other �ide of 1 TRUTH l Hl:SE\TS IU\ffi(W.\tYEHl\"S 1 11,i:1111111,1:11'1111;1111111 11111111:U 1\ 11.IZII.IH 11.1\lli I 111 ,11 I ISll.lll. n1,11, UH.Iii 236 24 FRAMES SATYA 13 RAM GOPAL VARMA, 1998 On 3 July, 1998, a previously untold story in the form of an unusual film came like a bolt from the blue. Ram Gopal Varma'sSatya was released all across India. A low-budget filmthat boasted no major stars, Satya continues to live in the popular imagination as one of the most powerful gangster filmsever made in India. Trained as a civil engineer and formerly the owner of a video store, Varma made his entry into the filmindustry with Shiva in 1989.