Una's Lectures, Delivered Annually on the Berkeley Campus, Memorialize Una Smith, Who Received Her B.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coins and Identity: from Mint to Paradise

Chapter 13 Coins and Identity: From Mint to Paradise Lucia Travaini Identity of the State: Words and Images on Coins The images and text imprinted with dies transformed disks of metal into coins and guaranteed them. The study of iconography on coins is therefore no less important than that of its other aspects, although each coinage should be studied together with the entire corpus of data and especially with reference where possible to its circulation.1 It may be difficult sometimes to ascertain how coin iconography was originally understood and received, but in most cases it is at least possible to know the idea behind the creation of different types, the choice of a model or of a language, as part of a crucial interaction of identity between the State and its coinage. We shall examine first some ex- amples of the creative phase, before minting took place, and then examples of how a sense of identity between the coins and the people who used them can be documented, concluding with a very peculiar use of coins as proof of identity for security at the entrance of gates of fortresses at Parma and Reggio Emilia in 1409.2 1 St Isidore of Seville stated in his Etymologiae that “in coins three things are necessary: metal, images and weight; if any of these is lacking it is not a coin” (in numismate tria quaeren- tur: metallum, figura et pondus. Si ex his aliquid defuerit nomisma non eriit) (Isidore of Seville, Origenes, Vol. 16, 18.12). For discussion of method, see Elkins and Krmnicek, Art in the Round, and Kemmers and Myrberg, “Rethinking numismatics”. -

ANALES De Arqueología Cordobesa

21/22 ANALES de Arqueología Cordobesa 2010 - 2011 21/22 de Arqueología Cordobesa de ANALES Gerencia Municipal de Urbanismo Área de Arqueología 2010 Grupo de investiGación sísifo 2011 Área de arqueoloGía. facultad de filosofía y letras. universidad de córdoba ANALES DE ARQUEOLOGÍA CORDOBESA núm. 21-22 (2010-2011) GRUpO de iNvEStiGACióN SÍSifO ÁREA de Arqueología. FacultAD de filosofÍA y LEtras. UNiversidad de Córdoba M.ª Teresa Amaré Tafalla In memoriam comité de redacción ANALES Director: DE ARQUEOLOGÍA Desiderio VAQUERIZO GIL Catedrático de Arqueología. Universidad de Córdoba CORDOBESA núm. 21-22 (2010-2011) Secretarios: José Antonio GARRIGUET Mata Universidad de Córdoba Alberto LEón MUñOZ Universidad de Córdoba Revista de periodicidad Vocales: anual, publicada por el Lorenzo ABAD CASAL Universidad de Alicante Grupo de Investigación Sí- Carmen ARAnEGUI GASCó Universidad de Valencia sifo (HUM-236, Plan An- Manuel BEnDALA GALÁn Universidad Autónoma de Madrid daluz de Investigación), Juan M. CAMPOS CARRASCO Universidad de Huelva de la Universidad de Cór- José L. JIMÉnEZ SALVADOR Universidad de Valencia doba, en el marco de su Pilar LEón-CASTRO ALOnSO Universidad de Sevilla convenio de colaboración Jesús LIZ GUIRAL Universidad de Salamanca con la Gerencia Municipal José María LUZón nOGUÉ de Urbanismo del Ayunta- Universidad Complutense de Madrid miento de la ciudad. Carlos MÁRQUEZ MOREnO Universidad de Córdoba Manuel A. MARTÍn BUEnO Universidad de Zaragoza Juan Fco. MURILLO REDOnDO Gerencia Municipal de Urbanismo. Ayto. de Córdoba Mercedes -

Process: the Example of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite

BARRY X BALL: REMAKING SCULPTURE Process: The Example of the Sleeping Hermaphrodite Barry X Ball reinvents traditional sculptural formats and existing art historical landmarks using state-of-the-art 3D scanning technology, computer-aided design (CAD) software, and computer- numerically-controlled (CNC) milling machines, in combination with centuries-old craft techniques requiring thousands of hours of detailed handwork. The Hermaphrodite Endormi (Sleeping Hermaphrodite) in the Louvre Museum in Paris offered an ideal starting point for Ball’s artistic explorations. Not only is the subject an embodiment of duality (see the object label and exhibition catalogue for more information on this), the object is a composite work of art interpreted by numerous authors over centuries. The figure is a second-century CE Roman copy of a second-century BCE Greek original. Discovered near the Baths of Diocletian in Rome in 1608, it joined the distinguished collection of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, who, in 1619, commissioned the young Gian Lorenzo Bernini to carve the mattress for it and David Larique to restore the figure. Ball continues this engagement with the work in the 21st century, reconsidering it for a contemporary audience and using the technological tools at his disposal. The illustrated review that follows elucidates the multi-step process Ball undertakes in making his Masterworks, like Sleeping Hermaphrodite. Ball works with museums to make extremely high-resolution three-dimensional digital scans of works of art. Because of their microscopic detail, the scans are very useful to the institutions charged with preserving the sculpture. Ball donates the scans to the museums for documentation and conservation and uses them Digital scanning of Hermaphrodite Endormi (Sleeping Hermaphrodite) in the Salle des Caryatids, as his point of departure for creating a new work. -

1. Compare and Contrast the High Renaissance Period with the Baroque Period

Preliminary Handout: David and Goliath Summarize the story of David and Goliath: How is David significant in Medici Florence? High Renaissance Period The Baroque Period Dates of the period: Dates of the period: Locations: Locations: Influences on the period: Influences on the period: Stylistic Characteristics: Stylistic Characteristics: Compare Donatello's David, Michelangelo's David, and Bernini’s David Donatello's David Michelangelo's David Bernini’s David Date Period Material Height Nude? Contrapposto? Moment in story: David represents... Original location: Stylistic Characteristics: Short Answer Essays: Please write a concise paragraph essay answering each of the questions below. You will work in groups and do a short two-minute presentation to the class on one question. 1. Compare and contrast the High Renaissance period with the Baroque period. What are the important influences and stylistic differences? 2. What are the primary defining elements of Italian Baroque sculpture and architecture? Select one Baroque sculpture and one Baroque building in Italy and discuss how they exemplify the style. 3. Compare and contrast Donatello, Michelangelo, and Bernini's David. How does each work embody the stylistic principles of its age? 4. Describe Bernini's Apollo and Daphne. What moment does it depict in Ovid's myth? Why would the Church approve of such a work? 5. How has Bernini drawn from his knowledge of theater, writing plays, and producing stage designs to create an emotionally dramatic experience for worshipers that involve architecture, sculpture, and painting at the Cornaro chapel? 6. How is Gianlorenzo Bernini’s work typical of the Baroque period? Give several examples of his work that support your answer. -

Michael Cowan Fitzgerald

1 Michael C. FitzGerald Office: 113 Hallden Hall tel. 860-297-2503 [email protected] [email protected] (home) EDUCATION 1976-1987 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Ph.D., M.Phil., M.A. DISSERTATION: "Pablo Picasso's Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire: Surrealism and Monumental Sculpture in France, 1918-1959." 1984-1986 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS M.B.A. 1972-1976 STANFORD UNIVERSITY B.A. EMPLOYMENT TRINITY COLLEGE (Hartford, CT) DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS 2007- Professor 2OO2-5 Director, Art History Program (first appointment) 1994-2007 Associate Professor, Department of Fine Arts 1996-1998 Chairman 1988-1994 Assistant Professor 1986-1988 CHRISTIE, MANSON AND WOODS INTERNATIONAL (New York, NY) Specialist-in-charge of Drawings, Department of Impressionist and Modern Art 1981-1983 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY (New York, NY) Preceptor,Department of Art History and Archaeology CONSULTANCY Research Director, Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz- Picasso para el Arte (FABA), 2020- AWARDS American Academy in Rome, April 2020 (deferred due to Corona Virus) Terra Foundation, 2006 2 National Endowment for the Arts, 2005-06 Faculty Research Leave, Trinity College, 2001-2002 3-Year Expense Grant, Trinity College, 2001-2004 Archives Grant, New York State Council of the Arts, 1999-2000 (with Whitney Museum of American Art) Fellowship, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1994-95 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer 1993 Travel to Collections Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer 1991 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer l989 Rudolf Wittkower Fellowship, Columbia University, 1980-81 Travel Grant, Columbia University, Summer l982; President's Fellowship, Columbia University, l977-78 CURRENT PROJECT Curator, Picasso and Classcial Traditions, This exhibition is a collaboration between the Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla and the Museo Picasso Málaga. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

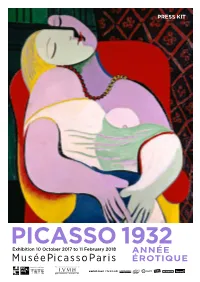

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Louis XIV: Art As Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17Th Century Europe

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Student Research Papers Research, Scholarship, and Resources Fall 11-30-2010 Louis XIV: Art as Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17th Century Europe Matthew Noblett [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/student-research-papers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Noblett, Matthew, "Louis XIV: Art as Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17th Century Europe" (2010). Student Research Papers. 1. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/student-research-papers/1 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Research, Scholarship, and Resources at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Louis XIV: Art as Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17th Century Europe Matthew D. Noblett 11/30/10 Dr. James Hutson ART 55400.31 Lindenwood University Noblett 1 In 17th century France there was national funding combined with strict controls placed on the arts and all areas of the administration of Louis XIV. This was imperative to present the country as one of the greatest European powers of its time. It was done by creating personas of Louis as the Sun King, sole administrator of France or “'L'etat c' est moi” (I am the State) and conqueror. All were reinforced and often invented in rigid confines through state funded propaganda. His name has become synonymous with the French arts of the 17th century through significant investments in all forms of media, from poetry, music and theatre to painting, sculpture and architecture. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/85949 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-07 and may be subject to change. KLIO 92 2010 1 65––82 Lien Foubert (Nijmegen) The Palatine dwelling of the mater familias:houses as symbolic space in the Julio-Claudian period Part of Augustus’ architectural programme was to establish „lieux de me´moire“ that were specifically associated with him and his family.1 The ideological function of his female relativesinthisprocesshasremainedunderexposed.2 In a recent study on the Forum Augustum, Geiger argued for the inclusion of statues of women among those of the summi viri of Rome’s past.3 In his view, figures such as Caesar’s daughter Julia or Aeneas’ wife Lavinia would have harmonized with the male ancestors of the Julii, thus providing them with a fundamental role in the historical past of the City. The archaeological evi- dence, however, is meagre and literary references to statues of women on the Forum Augustum are non-existing.4 A comparable architectural lieu de me´moire was Augustus’ mausoleum on the Campus Martius.5 The ideological presence of women in this monument is more straight-forward. InmuchthesamewayastheForumAugustum,themausoleumofferedAugustus’fel- low-citizens a canon of excellence: only those who were considered worthy received a statue on the Forum or burial in the mausoleum.6 The explicit admission or refusal of Julio-Claudian women in Augustus’ tomb shows that they too were considered exempla. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

This Exquisite Bronze Group Portrays the French Queen Marie Leczinska (1703-1768), Wife of King Louis XV (1710-1774), As The

MARIE LECZINSKA AS JUNO Bronze, on ormolu base Late 18th – early 19th Century, After a model by Guillaume Coustou the Elder (1677-1746) H 76 cm (with base) H 30 in This exquisite bronze group portrays the French Queen Marie Leczinska (1703-1768), wife of King Louis XV (1710-1774), as the Roman goddess Juno, the protectress and special counselor of the state. The qu een is depicted draped in the robes of a classical goddess and standing on a cloud. In her right hand she is holding the Crown of France, while a putto on her left offers her a scepter. Her right hand rests on a shield sporting the coat of arms of the French Monarchy. A peacock, Juno’s sacred animal, is sitting at her feet, curiously looking around. The deified queen is presented in a very individualized and youthful manner with extraordinary vividness and great charm. www.nicholaswells.com This group was closely modeled after a life-size marble original by Guillaume Coustou the Elder (1677-1746), that is currently part of the collection of sculptures of the Louvre (MR 1813) after having adorned a great number of royal residences throughout its existence. The original marble version of the group was commissioned in 1725, probably by the Directeur général des Bâtiments du Roi, the Duke of Antin. Guillaume Coustou the Elder seems to have been the logical choice for the project, since, at the time, his elder brother Nicolas had already started working on a pendant composition representing Louis XV as Jupiter (Louvre, MR 1811). For creating Marie Leczinska as Juno The Duchess of Burgundy as Diana, Coustou took some inspiration from the 1710, French, marble, by A. -

Income and Working Time of a Fencing Master in Bologna in the 15Th And

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Scholarly Volume, Articles 153 DOI 10.1515/apd-2016-0005 Income and working time of a Fencing Master in Bologna in the 15th and early 16th century Alessandro Battistini and Niki Corradetti translated by Luca Dazi, Sala d’Arme Achille Marozzo (www.achillemarozzo.it) [email protected], [email protected] Abstract – Since ancient times, the master-at-arms profession has always been considered essential for the education of the nobility and the common citizenship, especially in the Middle Ages. Yet, we know nothing about the real standard of living of these characters. The recent discovery of documents, which report the sums earned by fencing masters to teach combat disciplines, has brought us the possibility to estimate how highly this profession was regarded, and what its actual economic value was in the Italian late Middle Ages. They also give us also a material view into the modes of operation of a sala d’arme in those times. Using different comparative methods based on the quoted currencies, primary goods and the cost of living, it was possible to analyze prices and duration of various military teachings offered by the fencing Masters in the late Middle Ages and equivalent viable activities of the time. We use three ways to calculate equivalent income levels in euros: from the silver content of the coins (bolognini, equivalent to the soldo); from purchasing power in relation to bread prices; and from equivalent wages. As a result we were able to define more accurately both the accessibility of these services for citizens and the relative value to other professions. -

Art and Politics at the Neapolitan Court of Ferrante I, 1458-1494

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: KING OF THE RENAISSANCE: ART AND POLITICS AT THE NEAPOLITAN COURT OF FERRANTE I, 1458-1494 Nicole Riesenberger, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Department of Art History and Archaeology In the second half of the fifteenth century, King Ferrante I of Naples (r. 1458-1494) dominated the political and cultural life of the Mediterranean world. His court was home to artists, writers, musicians, and ambassadors from England to Egypt and everywhere in between. Yet, despite its historical importance, Ferrante’s court has been neglected in the scholarship. This dissertation provides a long-overdue analysis of Ferrante’s artistic patronage and attempts to explicate the king’s specific role in the process of art production at the Neapolitan court, as well as the experiences of artists employed therein. By situating Ferrante and the material culture of his court within the broader discourse of Early Modern art history for the first time, my project broadens our understanding of the function of art in Early Modern Europe. I demonstrate that, contrary to traditional assumptions, King Ferrante was a sophisticated patron of the visual arts whose political circumstances and shifting alliances were the most influential factors contributing to his artistic patronage. Unlike his father, Alfonso the Magnanimous, whose court was dominated by artists and courtiers from Spain, France, and elsewhere, Ferrante differentiated himself as a truly Neapolitan king. Yet Ferrante’s court was by no means provincial. His residence, the Castel Nuovo in Naples, became the physical embodiment of his commercial and political network, revealing the accretion of local and foreign visual vocabularies that characterizes Neapolitan visual culture.