Baumgartner Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Henry E. Brady

CURRICULUM VITAE Henry E. Brady July 11, 2016 Goldman School of Public Policy and Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Dean, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, July 2009-present. Class of 1941 Monroe Deutsch Professor of Political Science and Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley. 2003 to present. Robson Professor of Political Science and Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley. 2002-2003. Professor and Associate Professor of Political Science and Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley. July, 1990 to 2002 in the Department of Political Science and the Goldman School of Public Policy (starting 1991). Director, Survey Research Center, January 1, 1999 to July 31, 2009. The Survey Research Center conducted in- person, telephone, and self-administered surveys in the United States and California. Director---University of California Data Archive and Technical Assistance, July 1, 1992 to July 31, 2009. UC DATA (now D-Lab) is the University of California's principal archive for computerized census, social science, and health data. It works with researchers and government agencies to develop innovative datasets for research and policy-making. Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Chicago. January, 1987---1990 and Director, Center for the Study of Politics and Society, National Opinion Research Center, 1988---1990 Assistant Professor of Government, Harvard University. January, 1985---1987. Assistant Professor of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, 1978-1984. (Acting, 1978-1980.) EDUCATION Ph.D. in Economics and Political Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Fields included urban politics, public policy, political economy, political analysis, urban economics, econometrics, and public finance and public choice. -

Curriculum Vitae

September 2020 Andrea Louise Campbell Department of Political Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] Academic Positions Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Political Science Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science, 2015 – Faculty Affiliate, Center for Constructive Communication, MIT Media Lab, 2020 – Department head, 2015-19 Professor, 2012 - 2015 Associate Professor, 2005-12; tenured 2008 Alfred Henry and Jean Morrison Hayes Career Development Chair, 2006-09 Harvard University, Department of Government Assistant Professor, 2000-05 Lecturer, 1999-2000 Education Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley, Political Science, December 2000 M.A. University of California, Berkeley, Political Science, June 1994 A.B. Harvard University, Social Studies, magna cum laude, June 1988 Books Trapped in America’s Safety Net: One Family’s Struggle. University of Chicago Press, 2014. Featured in: Harvard Magazine; Washington Post Wonkblog; Vox; TIME Magazine; MIT Technology Review; MIT News; New Books in Political Science podcast; Faculti Media The Delegated Welfare State: Medicare, Markets, and the Governance of American Social Policy, with Kimberly J. Morgan. Oxford University Press, 2011. How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Citizen Activism and the American Welfare State. Princeton University Press, 2003. Paperback edition, 2005. Campbell, p. 2 Textbook We the People: An Introduction to American Politics, with Benjamin Ginsberg, Theodore J. Lowi, Caroline J. Tolbert, and Margaret Weir. W.W. Norton, beginning 12th edition, 2019. Articles “The Social, Political, and Economic Effects of the Affordable Care Act: Introduction to the Issue,” with Lara Shore-Sheppard. RSF: Russell Sage Foundation Journal 6; 2 (June 2020): 1- 40. “The Affordable Care Act and Mass Policy Feedbacks.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 45; 4 (August 2020): 567-80. -

Organizations and the Democratic Representation of Interests: What Does It Mean When Those Organizations Have No Members?

Reflections Organizations and the Democratic Representation of Interests: What Does It Mean When Those Organizations Have No Members? Kay Lehman Schlozman, Philip Edward Jones, Hye Young You, Traci Burch, Sidney Verba, and Henry E. Brady This article documents the prevalence in organized interest politics in the United States of organizations—for example, corporations, think tanks, universities, or hospitals—that have no members in the ordinary sense and analyzes the consequences of that dominance for the democratic representation of citizen interests. We use data from the Washington Representatives Study, a longitudinal data base containing more than 33,000 organizations active in national politics in 1981, 1991, 2001, 2006, and 2011. The share of membership associations active in Washington has eroded over time until, in 2011, barely a quarter of the more than 14,000 organizations active in Washington in 2011 were membership associations, and less than half of those were membership association with individuals as members. In contrast, a majority of the politically involved organizations were memberless organizations, of which nearly two-thirds were corporations. The dominance of memberless organizations in pressure politics raises important questions about democratic representation. Studies of political representation by interest groups raise several concerns about democratic inequalities: the extent to which representation of interests by groups is unequal, the extent to which groups fail to represent their members equally, and the extent to which group members are unable to control their leaders. All of the dilemmas that arise when membership associations advocate in politics become even more intractable when organizations do not have members. rganized interests play a significant role in the Kay Lehman Schlozman is the J. -

IMAGES of an UNBIASED INTEREST SYSTEM David Lowery, Frank R

This article was downloaded by: [Frank Baumgartner] On: 10 June 2015, At: 15:58 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of European Public Policy Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjpp20 IMAGES OF AN UNBIASED INTEREST SYSTEM David Lowery, Frank R. Baumgartner, Joost Berkhout, Jeffrey M. Berry, Darren Halpin, Marie Hojnacki, Heike Klüver, Beate Kohler-Koch, Jeremy Richardson & Kay Lehman Schlozman Published online: 10 Jun 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: David Lowery, Frank R. Baumgartner, Joost Berkhout, Jeffrey M. Berry, Darren Halpin, Marie Hojnacki, Heike Klüver, Beate Kohler-Koch, Jeremy Richardson & Kay Lehman Schlozman (2015) IMAGES OF AN UNBIASED INTEREST SYSTEM, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:8, 1212-1231 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1049197 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Vol. 46, Fall 2015

NEW YORK ECONOMIC REVIEW FALL 2015 NYSEA JOURNAL of the NEW YORK STATE ECONOMICS ASSOCIATION VOLUME XLVI NEW YORK STATE ECONOMICS ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1948 2014-2015 OFFICERS President: MANIMOY PAUL SIENA COLLEGE Vice-President: XU ZHANG SUNY FARMINGDALE Secretary: MICHAEL McAVOY SUNY ONEONTA Treasurer: DAVID RING SUNY ONEONTA Editor: WILLIAM P. O’DEA SUNY ONEONTA Web Coordinator: ERYK WDOWIAK SUNY FRAMINGDALE Board of Directors: CYNTHIA BANSAK St. LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY KPOTI KITISSOU SKIDMORE COLLEGE FANGXIA LIN CUNY NEW YORK CITY COLLEGE of TECHNOLOGY SEAN MacDONALD CUNY NEW YORK CITY COLLEGE of TECHNOLOGY ABEBA MUSSA SUNY FARMINGDALE PHILIP SIRIANNI SUNY ONEONTA CLAIR SMITH St. JOHN FISHER COLLEGE WADE THOMAS SUNY ONEONTA JEFFREY WAGNER ROCHESTER INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY The views and opinions expressed in the Journal are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent those of individual staff members. NEW YORK ECONOMIC REVIEW New York Economic Review Vol. 46, Fall 2015 CONTENTS ARTICLES Estimating the Marginal Value of Agents in Major League Baseball Tyler Wasserman and Rodney Paul…………………………………………….……………..3 Immigrants Financing Immigrants: A Case Study of a Chinese-American Rotating Savings and Credit Association in Queens Xiaoyu Wu and Teresa D. Hutchins………………..………………...……………………....21 Issues in the Sustainability of the Medicare Program Larry L. Lichtenstein and Mark P. Zaporowski…….………………...………………….…..35 The Determinants of Political Participation Mark Gius……………………………………………………………………………...……..…53 Brownfield Assessments, Cleanups, and Development: How Do We Measure Success Christopher N. Annala and Ryan M. Smith………………………….………………...…….63 Public Housing, Rent Subsidy: A Comparative Panel Analysis on the Effects on Education and Earnings Diamondo Afxentiou………………..………………………………………………….…….…82 Referees………………………………………………...…………………………………….….……100 Final Program (67th Annual Convention-October 10-11, 2014)……………………….......….101 1 FALL 2015 EDITORIAL The New York Economic Review is an annual journal, published in the fall. -

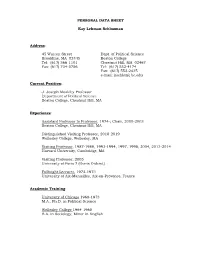

Personal Data Sheet

PERSONAL DATA SHEET Kay Lehman Schlozman Address: 45 Warren Street Dept. of Political Science Brookline, MA 02445 Boston College Tel: (617) 566-1101 Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 Fax: (617) 734-5756 Tel: (617) 552-4174 Fax: (617) 552-2435 e-mail: kschloz@ bc.edu Current Position: J. Joseph Moakley Professor Department of Political Science Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA Experience: Assistant Professor to Professor, 1974-; Chair, 2000-2003 Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA Distinguished Visiting Professor, 2018-2019 Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA Visiting Professor, 1987-1988, 1993-1994, 1997, 1998, 2004, 2013-2014 Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Visiting Professor, 2005 University of Paris 7 (Denis Diderot) Fulbright Lecturer, 1972-1973 University of Aix-Marseilles, Aix-en-Provence, France Academic Training: University of Chicago 1968-1973 M.A., Ph.D. in Political Science Wellesley College 1964-1968 B.A. in Sociology; Minor in English 2 Fellowships and Awards: Warren E. Miller Lifetime Achievement Award, Section on Elections, Public Opinion and Voting Behavior, American Political Science Association, 2018. Samuel J. Eldersveld Career Achievement Lifetime Award, Section on Political Organizations and Parties, American Political Science Association, 2016. Resident Scholar, Bellagio Center of the Rockefeller Foundation, Bellagio, Italy, October-November, 2015 PROSE Awards, Government and Politics and Excellence in Social Sciences, American Association of Publishers, 2012 AAPOR Book Award, American Association for Public Opinion Research, -

Nancy Burns' Curriculum Vitae

Nancy Burns Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE NANCY BURNS Warren E. Miller Collegiate Professor of Political Science University of Michigan 5700 Haven Hall 505 South State Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1045 Phone: (734) 763-3080 E-mail Address: [email protected] April 2018 Education Ph.D. 1991 Harvard University (Political Science) Ph.D. Dissertation: “Making Politics Permanent” Ph.D. Committee: Sidney Verba (Chair), Gary King, Paul Peterson, and Kay Lehman Schlozman M.A. 1988 Harvard University (Political Science) B.A. 1986 University of Kansas (Political Science) Professional Experience 2014-Present Chair. Department of Political Science. University of Michigan. 2003-Present Professor. Department of Political Science. University of Michigan. 2004-Present Warren E. Miller Collegiate Professor. University of Michigan. 2005-2014. Director, Center for Political Studies, University of Michigan. 1991-Present Faculty Associate to Research Professor. Center for Political Studies. Institute for Social Research. University of Michigan. 2006-2007 Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Palo Alto, California. 1999-2006 Principal Investigator, American National Election Studies. 1999-2004 Henry Simmons Frieze Collegiate Professor. University of Michigan. 1997-2003 Associate Professor. University of Michigan. Department of Political Science. 1998-2001 Program Director. Institute for Research on Women and Gender. University of Michigan. 1991-1997 Assistant Professor. University of Michigan. Department of Political Science. 1994-1995 Visiting Assistant Professor of Government. Harvard University. Department of Government. 1990-1991 Assistant Research Scientist. University of Michigan. Department of Political Science and the Institute for Social Research. Nancy Burns Page 2 Books 2001 The Private Roots of Public Action: Gender, Equality, and Political Participation. -

Deliberative Abilities and Influence in a Transnational Deliberative Poll

Erschienen in: British Journal of Political Science ; 48 (2018), 04. - S. 1093-1118 https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000144 B.J.Pol.S. 48, 1093–1118 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S0007123416000144 First published online 15 September 2016 Deliberative Abilities and Influence in a Transnational Deliberative Poll (EuroPolis) MARLÈNE GERBER, ANDRÉ BÄCHTIGER, SUSUMU SHIKANO, SIMON REBER AND SAMUEL ROHR* This article investigates the deliberative abilities of ordinary citizens in the context of ‘EuroPolis’,a transnational deliberative poll. Drawing upon a philosophically grounded instrument, an updated version of the Discourse Quality Index (DQI), it explores how capable European citizens are of meeting delib- erative ideals; whether socio-economic, cultural and psychological biases affect the ability to deliberate; and whether opinion change results from the exchange of arguments. On the positive side, EuroPolis shows that the ideal deliberator scoring high on all deliberative standards does actually exist, and that participants change their opinions more often when rational justification is used in the discussions. On the negative side, deliberative abilities are unequally distributed: in particular, working-class members are less likely to contribute to a high standard of deliberation. Keywords: deliberation; deliberative polls; European Union; citizen participation; working class. Confronted with a malaise of democratic governance and the disenchantment of citizens with politics, recent years have witnessed a worldwide boom in participatory and deliberative citizen events. The idea is that democratic innovations might not only help to narrow the gap between politicians and citizens but also serve as a policy-consultation device. Yet, if democratic innovations should become a regular component of democratic governance, it is essential to know whether they do in fact function as their proponents suggest. -

African-American Conventional and Unconventional Political Participation

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu Common fate is considered essential to black collective identity, solidarity, and mobilization. 1 Tate (1991, 1994, 2003), for example, finds that feelings of common fate and Black identity increases Black rates of political participation. Citing a recent survey of African Americans nationwide, Bobo, Dawson, and Johnson (2001) emphasize the “durable two-ness of the African-American experience” as indicated by the continued strong feelings of common fate among “nearly a third of the black population.” Sociological theories have long held that collective identity and feelings of solidarity are critical to protest and movement participation (Melucci 1988:334; Hunt and Benford 2004:437; Klandermans 2004:366-367). Polletta and Jasper (2001:3) define collective identity as “an individual’s cognitive, moral, and emotional connection with a broader community, category, practice, or institution. It is a perception of a shared status or relation.” Derived from group membership in a social category that similarly experiences social relations (Tilly 2002:19), collective identity is a “shared sense of ‘we-ness” (Hunt and Benford 2004:440), and “common cause, threat, or fate” (Snow 2001:2214). While, empirically, this study aims to increase our knowledge of political participation among African Americans, it also seeks to expand our methodological approach and theoretical understanding concerning the relative importance of collective identity in predicting the likelihood of political participation. This paper expands upon the considerable body of work that asks why some individuals choose to participate in political activities while others do not. -

Kristi Andersen CV

Kristi Andersen Department of Political Science Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs Syracuse University Syracuse, New York 13244 (315) 443-2416 [email protected] 11 Rippleton Road Cazenovia, New York 13035 (315) 655-2007 Education University of Chicago: M.A., 1973; Ph.D., 1976 Smith College: B.A. magna cum laude, 1969 Professional Experience Department of Political Science, Syracuse University: Professor Emeritus, 2016- ; Professor, 1996-2016 ; Associate Professor, 1984-1996. Department Chair 1996-2001; Graduate Studies Director, 1985-1993 and 1996-1998; Undergraduate Director, 2004-2011. Department of Political Science, The Ohio State University: Associate Professor, 1979-1984; Assistant Professor, 1976-1979; Instructor, 1975-1976; Director, Polimetrics Laboratory, Ohio State University, 1981-1984; Associate Director, 1978-1981. Associate Study Director, National Opinion Research Center, Chicago, 1973-1975. Courses taught: Undergraduate courses: Critical Issues for the U.S.; Quantitative Methods for the Social Sciences; Political Argument and Reasoning; Introduction to American Politics; Public Opinion; Political Parties; Political Behavior; Women and Politics; Women and Leadership; Comparative Social Movements; Politics and Architecture. Graduate courses: Research Design in Political Analysis; Women and Politics; Gender and Politics; Introduction to Quantitative Research Methods; Public Opinion and Voting Behavior; American Political Parties; Political Psychology; Political Socialization; Research and Writing Seminar. -

Virginia Sapiro

VIRGINIA SAPIRO PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL SCIENCE DEAN OF ARTS & SCIENCES EMERITA DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, 232 BAY STATE ROAD, RM. 313A BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02215 [email protected] @VSAPIRO http://blogs.bu.edu/vsapiro ACADEMIC AND ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS BOSTON UNIVERSITY, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, 2007- Professor of Political Science, 2007- present Dean of Arts & Sciences Emerita, 2017- present Dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (CAS) (2007-2015) CAS contains 22 departments, one school, and more than 30 interdisciplinary programs and centers, over 60 undergraduate majors, 55 M.A. programs, 2 MFAs, and 30 Ph.D. programs. Almost 7,000 undergraduates and 2,000 graduate students pursue degrees in CAS. Undergraduates in the 9 other BU schools and colleges with undergraduate degree programs take an average of 40% of their credits in CAS. In FY15 CAS occupied ~38 buildings and had an operating budget of about $110M. Responsible for raising ~$100M. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN – MADISON, 1976-2007 Sophonisba P. Breckinridge Professor Emerita and Associate Vice Chancellor Emerita, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 2007- present Interim Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs, 11/2005-3/06 Vice Provost (Associate Vice Chancellor) for Teaching and Learning, Office of the Provost, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 2002-06 Faculty Affiliate, Wisconsin Center for the Advancement of Post-Secondary Education (WISCAPE), 2007 Associate Chair, Women’s Studies Program, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 2000-01 Sophonisba -

American Citizen Participation Study, 1990 Data Collection Instrument

ICPSR Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research American Citizen Participation Study, 1990 Data Collection Instrument Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman, Henry E. Brady, and Norman Nie ICPSR 6635 This document was previously available in paper format only. It was converted to Portable Document Format (PDF), with no manual editing, on the date below as part of ICPSR's electronic document conversion project. The document may not be completely searchable. No additional updating of this collection has been performed (pagination, missing pages, etc.). June 2002 .I ICPSR Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research American Citizen Participation Study, 1990 Data Collection Instrument Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman, Henry E. Brady, and Norman Nie ICPSR 6635 AMERICAN CITIZEN PARTICIPATION STUDY, 1990 (ICPSR 6635) Principal Investigators Sidney Verba, Harvard University Kay Lehman Schlozman, Boston College Henry E. Brady, University of California, Berkeley Norman Nie, University of Chicago First ICPSR Version November 1995 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 BIBLIOGRAPHIC CITATION Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, Henry E. Brady, and Norman Nie. AMERICAN CITIZEN PARTICIPATION STUDY, 1990 [Computer file]. ICPSR version. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center (NORC) [producer], 1995. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter- university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1995.