The Effectiveness of the U.S. Government's Response To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Loophole in Financial Accounting: a Detailed Analysis of Repo

The Journal of Applied Business Research – September/October 2011 Volume 27, Number 5 A Loophole In Financial Accounting: A Detailed Analysis Of Repo 105 Chun-Chia (Amy) Chang, Ph.D., San Francisco State University, USA Joanne Duke, Ph.D., San Francisco State University, USA Su-Jane Hsieh, Ph.D., San Francisco State University, USA ABSTRACT From 2000 to 2008, Lehman used repo transactions to hide billions of dollars on their statements. They also misrepresented the repo transactions as “secured borrowings” even though they actually recorded the transactions as sales. Valukas’ report in 2010 stimulated an extensive coverage of the repo transactions and spurred an array of studies addressing issues related to the collapse of financial institutions. Since the Repo 105 maneuver of Lehman provides a good example on how regulatory deficiencies can induce companies to obscure financial reporting and the importance of ethics in deterring these abuses, our study intends to examine repo transactions related accounting standards, illustrate how repo transactions can enhance a bank’s financial statements, and discuss the importance of business ethics in curtailing accounting irregularities. Keywords: Repo 105; creative accounting; business ethics INTRODUCTION n March 2010, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ hereafter) published a series of reports regarding a practice called Repo 105 that was employed by the Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. to obscure approximately $50 billion of liabilities from investors.1 A “Repo” is a “repurchase agreement” that enables short-term Iborrowers to gain liquidity. During a repo transaction, a company “sells” assets to others with a repurchase agreement signed simultaneously at the time of the sale. -

11 What Is Risk Assessment? 185 12 Risk Analysis 195 13 Who Is Responsible? 207

RISK MANAGEMENT FOR COMPUTER SECURITY This Page Intentionally Left Blank RISK MANAGEMENT FOR COMPUTER SECURITY Protecting Your Network and Information Assets By Andy Jones & Debi Ashenden AMSTERDAM ● BOSTON ● HEIDELBERG ● LONDON NEW YORK ● OXFORD ● PARIS ● SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO ● SINGAPORE ● SYDNEY ● TOKYO Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2005, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permis- sion of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://books.elsevier.com/security), by selecting “Customer Support” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” ϱ Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier-Science prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Andy. Risk management for computer security: protecting your network and information assets/Andy Jones and Debi Ashenden. —1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7506-7795-3 (alk. paper) 1. Industrial safety—Management. 2. Computer -

Enron and Co

Enron and Co. - the fiasco of the new USA-style economy Eric Toussaint (*) Twenty years of deregulation and market liberalization on a planetary scale have eliminated all the safety barriers that might have prevented the cascade effect of crises of the Enron type. All capitalist companies of the Triad and emerging markets have evolved, some with their own variations, on the same lines as in the USA. The planet's private banking and financial institutions (as well as insurance companies) are in a bad way, having adopted ever riskier practices. The big industrial groups have all undergone a high degree of financialization and they, too, are very vulnerable. The succession of scandals shows just how vacuous are the declarations of the US leaders and their admirers in the four corners of the globe (see Ahold, Parmalat,…). A mechanism equivalent to several time -bombs is under way on the scale of all the economies on the planet. To name just a few of those bombs: over indebtedness of companies and households, the derivatives market (which in the words of the billionaire Warren Buffet, are « financial weapons of mass destruction »), the bubble of property speculation (most explosive in the USA and the UK), the crisis of insurance companies and that of pension funds. It is time to defuse these bombs and think of another way of doing things, in the USA and elsewhere. Of course, it is not enough to defuse the bombs and dream of another possible world. We have to grapple with the roots of the problems by redistributing wealth on the basis of social justice. -

Asset Sales Or Loans: the Case of Lehman Brothers' Repo 105S Chao

THE ACCOUNTING EDUCATORS’ JOURNAL Volume XXI 2011 pp. 79- 88 Asset Sales or Loans: The Case of Lehman Brothers’ Repo 105s Chao-Shin Liu University of Notre Dame Thomas F. Schaefer University of Notre Dame Abstract Lehman Brothers, Inc. was one of the very early casualties of the 2008-09 worldwide financial crisis becoming the largest bankruptcy of a U.S. financial institution. Prior to its demise, Lehman Brothers periodically employed an accounting technique known as Repo 105 for its financial reporting of certain transactions involving repurchase agreements. The Repo 105 accounting allowed Lehman to temporarily reduce its debt levels during periods that included financial statement preparation. The purpose of this case is to summarize the accounting for Lehman Brothers’ Repo 105 transactions, present some classroom discussion points, and provide student review questions related to accounting and financial reporting issues underlying the Repo 105 transactions. Background On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers, a former global financial services firm, became the largest firm at the time to declare bankruptcy in United States history. In several time periods prior to the bankruptcy, Lehman employed an accounting technique euphemistically referred to as either “Repo 105” or “Repo 108.”Although the role of these repurchase agreements in the bankruptcy is not completely clear, many argue that the technique enabled Lehman Brothers to hide large amounts of liabilities for the purpose of misinforming investors, business partners, and regulators. -

Sarbanes-Oxley and Corporate Greed Adria L

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-8-2011 Sarbanes-Oxley and Corporate Greed Adria L. Stigliano University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons Recommended Citation Stigliano, Adria L., "Sarbanes-Oxley and Corporate Greed" (2011). Honors Scholar Theses. 207. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/207 Sarbanes-Oxley & Corporate Greed Adria L. Stigliano Spring 2011 Sarbanes-Oxley & Corporate Greed Adria L. Stigliano Spring 2011 Adria L. Stigliano Honors Thesis Spring 2011 Sarbanes-Oxley and Corporate Greed Sigmund Freud, the Austrian psychologist, believed that every human being is mentally born with a “clean slate”, known as Tabula rasa , where personality traits and character are built through experience and family morale. Other psychologists and neurologists believe individuals have an innate destiny to be either “good” or “bad” – a more fatalistic view on human life. Psychological theories are controversial, as it seems almost impossible to prove which theory is reality, but we find ourselves visiting these ideas when trust, ethics, reputation, and integrity are violated. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act is still a relatively new federal law set forth by the Securities Exchange Commission in 2002. Since its implementation, individuals have been wondering if Sarbanes-Oxley is effective enough and doing what it is meant to do – catch and prevent future accounting frauds and scandals. With the use of closer and stricter rules, the SOA is trying to prevent frauds with the use of a created Public Company Accounting Oversight Board. -

Reforming the Auditing Industry

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330983629 REFORMING THE AUDITING INDUSTRY Technical Report · December 2018 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15538.04802 CITATIONS READS 4 2,647 14 authors, including: Prem Sikka Christine Cooper University of Sheffield and University of Essex University of Strathclyde 118 PUBLICATIONS 3,957 CITATIONS 28 PUBLICATIONS 1,192 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE John Christensen Paddy Ireland Tax Justice Network University of Bristol 30 PUBLICATIONS 718 CITATIONS 40 PUBLICATIONS 732 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: EURAM 2019, Lisbon, Rethinking the Form, Governance & Legal Constitution of Corporations. Theoretical Issues & Social Stakes. View project Project on property rights and China View project All content following this page was uploaded by Prem Sikka on 09 February 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. REFORMING THE AUDITING INDUSTRY Prem Sikka Colin Haslam Christine Cooper James Haslam John Christensen Deepa Govindarajan Driver Tom Hadden Paddy Ireland Martin Parker Gordon Pearson Ann Pettifor Sol Picciotto Jeroen Veldman Hugh Willmott *REFORMING THE AUDITING INDUSTRY This review was commissioned by the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, John McDonnell MP, and conducted independently by Professor Prem Sikka and others. The contents of this document form a submission to Labour’s policy making process; they do not constitute Labour Party policy nor should the inclusion of conclusions and recommendations be taken to signify Labour Party endorsement for them. This report is promoted by John McDonnell MP, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer at House of Commons, Westminster, London SW1A 0AA. -

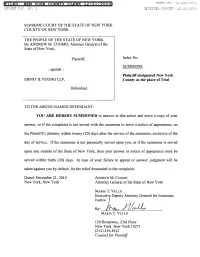

Filed: New York County Clerk 12/21/2010 Index No

FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 12/21/2010 INDEX NO. 451586/2010 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 1 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 12/21/2010 SUPREME COURT OF TH:E STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK By ANDREW M. CUOMO, Attorney General ofthe State ofNew York, Plaintiff, Index No. SUMMONS - against- Plaintiff designated New York ERNST & YOUNG LLP, County as the place of Trial Defendant. TO THE ABOVE-NAMED DEFENDANT: YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED to answer in this action and serve a copy of your answer, or if the complaint is not served with the summons to serve a notice of appearance, on the Plaintiffs attorney within twenty (20) days after the service ofthe summons, exclusive of the day of service. If the summons is not personally served upon you, or if the summons is served upon you outside of the State of New York, then your answer or notice of appearance must be served within thirty (30) days. In case of your failure to appear or answer, judgment will be taken against you by default, for the relief demanded in the complaint. Dated: December 21,2010 ANDREW M. CUOMO New York, New York Attorney General ofthe State ofNew York MARIA T. VULLO Executive Deputy Attorney General for Economic JusticeL By: J1/A MARIA T. VULLO 120 Broadway, 23rd Floor New York, New York 10271 (212) 416-8521 Counselfor Plaintiff SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK By ANDREW M. CUOMO, Attorney General of the State of New York, Plaintiff, Index No. -

Creative Accounting Practices Pdf

Creative accounting practices pdf Continue Euphemism, referring to unethical accounting practice Of Book Preparation, redirects here. For an episode of Black Books, see Cooking Books (Black Books episode). For the New York-tv cooking programme, watch the Cook Books Program (TV program). Part of the series onAccounting Historical Expenses Permanent Purchasing Power Office Tax Main Types Audit Budget Expenditures Forensic Fund State Office Social Tax Key Concepts Period Accrual Permanent Purchasing Power Economic Essence Fair Value Going Historical Concerns Historical Costs Compliance Principle Materiality Income Recognition Unit Account Selected Cash Account Cash Expenses Goods, Sold Amortization/Amortization of Equity Expenses Goodwill Passion principles Financial Reporting Annual Report Balance Sheet Cash Flow Income Office Discussion Notes to Financial Reporting Accountant Bank Reconciliation Of Debits and Loans Double Entry System FIFO and LIFO Journal Ledger / General Registry T Accounts Forensic Balance Audit Of Financial Firms Report by People and Organization Accountants Accounting Organizations but deviate from the spirit of these rules with questionable accounting ethics, in particular misrepresenting the results in favor of training, or the firm that hired the accountant. They are characterized by excessive complications and the use of new ways of characterizing income, assets or liabilities and the intention to influence readers with respect to interpretations desired by the authors. Sometimes the terms are also innovative or aggressive. Another common synonym is the preparation of books. Creative accounting is often used in tandem with outright financial fraud (including securities fraud), and the boundaries between them are blurred. Creative accounting techniques have been known since ancient times and appear all over the world in various forms. -

Corporate Collapse and the Role of Audit Committees: a Case Study of Lehman Brothers

World Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 7. No. 1. March 2017. Pp. 19 – 29 Corporate Collapse and the Role of Audit Committees: A Case Study of Lehman Brothers Abdullahi Adamu Dodo* This paper examined the roles and effectiveness of Audit Committees (herein ACs) as provided by corporate governance codes, in relation to corporate failures, whether the failure is as a result of the ineffectiveness of the ACs. Given that the AC is perceived to be a means of strengthening the external financial reporting process and facilitating the detection and prevention of corporate misconducts and scandals. It is believed that many financial and governance failures experienced in the recent past could be detected much earlier, had ACs been discharging their duties effectively. Secondary sourced data were used to investigate the roles of AC in the case of Lehman Brother’s corporate failure. A qualitative case study method was employed to carry out the study, by identifying and evaluating specific areas of interaction between ACs and other parties which affect audit process. The finding shows that many corporate failures are associated with the ineffectiveness of ACs, and that ACs could have prevented the occurrence of several corporate failures if they were efficient. However, the ACs cannot be 100% blamed for the failures, this is because their effectiveness is subjected to so many factors, and lack of any one factor always renders the AC ineffective. Some of the findings are consistent, while others are contrary to previous empirical studies on effectiveness of ACs. The study exposed specifically the process involved in the conduct of ACs in an organization and this add to the current debate on the need for improvement in the roles played by the AC as public gatekeepers. -

Lehman's Demise and Repo 105: No Accounting for Deception: Knowledge@Wharton (

Lehman's Demise and Repo 105: No Accounting for Deception: Knowledge@Wharton (http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2464) Lehman's Demise and Repo 105: No Accounting for Deception Published : March 31, 2010 in Knowledge@Wharton The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 is widely seen as the trigger for the financial crisis, spreading panic that brought lending to a halt. Now a 2,200-page report says that prior to the collapse -- the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history -- the investment bank's executives went to extraordinary lengths to conceal the risks they had taken. A new term describing how Lehman converted securities and other assets into cash has entered the financial vocabulary: "Repo 105." While Lehman's huge indebtedness and other mistakes have been well documented, the $30 million study by Anton Valukas, This is a single/personal use copy of Knowledge@Wharton. For multiple copies, custom reprints, e-prints, posters or assigned by the bankruptcy court, contains a number of surprises plaques, please contact PARS International: and new insights, several Wharton faculty members say. [email protected] P. (212) 221-9595 x407. Among the report's most disturbing revelations, according to Wharton finance professor Richard J. Herring, is the picture of Lehman's accountants at Ernst & Young. "Their main role was to help the firm misrepresent its actual position to the public," Herring says, noting that reforms after the Enron collapse of 2001 have apparently failed to make accountants the watchdogs they should be. "It was clearly a dodge.... to circumvent the rules, to try to move things off the balance sheet," says Wharton accounting professor professor Brian J. -

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and Ethical Corporate Climates: What the Media Reports; What the General Public Knows, 2 Brook

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 4 2008 The aS rbanes-Oxley Act and Ethical Corporate Climates: What the Media Reports; What the General Public Knows Cheryl L. Wade Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Recommended Citation Cheryl L. Wade, The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and Ethical Corporate Climates: What the Media Reports; What the General Public Knows, 2 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2008). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT AND ETHICAL CORPORATE CLIMATES: WHAT THE MEDIA REPORTS; WHAT THE GENERAL PUBLIC KNOWS Cheryl L. Wade* I. INTRODUCTION The question for participants in the Securities Regulation Section’s program at the 2008 AALS Annual Meeting was whether recent securities regulation reforms hit their mark. I focus in this essay on The Sarbanes- Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX or the Act),1 the most important legislative reform of securities markets in recent decades.2 Enacted to assuage public outrage about corporate greed and malfeasance ignited by media reports describing debacles at Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, Tyco and other companies in 2001 and 2002 (the Corporate Scandals)3, SOX represented a legislative and political response to public resentment of what some considered a morally impaired corporate America. In the immediate aftermath of its enactment, the mark at which SOX took aim was the allaying of public indignation. -

The Role Enron Energy Service, Inc., (Eesi) Played in the Manipulation of Western State Electricity Markets

S. HRG. 107–1139 THE ROLE ENRON ENERGY SERVICE, INC., (EESI) PLAYED IN THE MANIPULATION OF WESTERN STATE ELECTRICITY MARKETS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 18, 2002 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 83–978 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:07 Sep 26, 2005 Jkt 083978 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\83978.TXT JACK PsN: JACKF SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts CONRAD BURNS, Montana JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RON WYDEN, Oregon OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MAX CLELAND, Georgia SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas BARBARA BOXER, California GORDON SMITH, Oregon JOHN EDWARDS, North Carolina PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois JEAN CARNAHAN, Missouri JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BILL NELSON, Florida GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia KEVIN D. KAYES, Democratic Staff Director MOSES BOYD, Democratic Chief Counsel JEANNE BUMPUS, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:07 Sep 26, 2005 Jkt 083978 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\83978.TXT JACK PsN: JACKF C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on July 18, 2002 ..............................................................................