Sigur Rós's Heima

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

L'hantologie Résiduelle, L'hantologie Brute, L'hantologie Traumatique*

Playlist Society Un dossier d’Ulrich et de Benjamin Fogel V3.00 – Octobre 2013 L’hantologie Trouver dans notre présent les traces du passé pour mieux comprendre notre futur Sommaire #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie #2 : L’hantologie brute #3 : L’hantologie résiduelle #4 : L’hantologie traumatique #5 : Portrait de l’artiste hantologique : James Leyland Kirby #6 : Une ouverture (John Foxx et Public Service Broadcasting) L’hantologie - Page | 1 - Playlist Society #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie Par Ulrich abord en 2005, puis essentiellement en 2006, l’hantologie a fait son D’ apparition en tant que courant artistique avec un impact particulièrement marqué au niveau de la sphère musicale. Évoquée pour la première fois par le blogueur K-Punk, puis reprit par Simon Reynolds après que l’idée ait été relancée par Mike Powell, l’hantologie s’est imposée comme le meilleur terme pour définir cette nouvelle forme de musique qui émergeait en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis. A l’époque, cette nouvelle forme, dont on avait encore du mal à cerner les contours, tirait son existence des liens qu’on pouvait tisser entre les univers de trois artistes : Julian House (The Focus Group / fondateur du label Ghost Box), The Caretaker et Ariel Pink. C’est en réfléchissant sur les dénominateurs communs, et avec l’aide notamment de Adam Harper et Ken Hollings, qu’ont commencé à se structurer les réflexions sur le thème. Au départ, il s’agissait juste de chansons qui déclenchaient des sentiments similaires. De la nostalgie qu’on arrive pas bien à identifier, l’impression étrange d’entendre une musique d’un autre monde nous parler à travers le tube cathodique, la perception bizarre d’être transporté à la fois dans un passé révolu et dans un futur qui n’est pas le nôtre, voilà les similitudes qu’on pouvait identifier au sein des morceaux des trois artistes précités. -

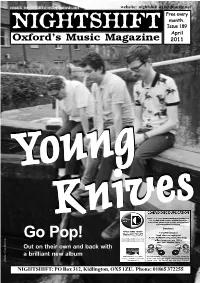

Issue 189.Pmd

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Dennis Morris: Pil - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room

ICA For immediate release: 13 January 2016 Dennis Morris: PiL - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Album cover image from PiL’s first album Public Image: First Issue (1978). © Dennis Morris – all rights reserved. The ICA presents rarely seen photographs and ephemera relating to the early stages of the band Public Image Ltd’s (PiL) design from 1978-79 with a focus on the design of the album Metal Box. Original band members included John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten - vocals), Keith Levene (lead guitar), Jah Wobble (bass) and Jim Walker (drums). Working closely with photographer and designer Dennis Morris, the display explores the evolution of the band’s identity, from their influential journey to Jamaica in 1978 to the design of the iconic Metal Box. Set against a backdrop of political and social upheaval in the UK, the years 1978-79 marked a period that hailed the end of the Sex Pistols and the subsequent shift from Punk to New Wave. Morris sought to capture this era by creating a strong visual identity for the band. His subsequent designs further aligned PiL with a style and attitude that announced a new chapter in music history. For PiL’s debut single Public Image, Morris designed a record sleeve in the format of a single folded sheet of tabloid newspaper featuring fictional content about the band. His unique approach to design was further illustrated by the debut PiL album, Public Image: First Issue (1978). In a very un-Punk manner, its cover and sleeve design imitated the layout of popular glossy magazines. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

Jazz, Identity and Sound Design in a Melting Pot

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Lauri Kallio Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 HEC, Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Spring, 2019 Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 higher education credits Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring, 2019 Author: Lauri Kallio Title: Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Supervisor: Dr. Joel Eriksson Examiner: ABSTRACT In this piece of artistic research the author explores his musical toolbox and aesthetics for creating music. Finding compositional and music productional identity are also the main themes of this work. These aspects are being researched through the process creating new music. The author is also trying to build a bridge between his academic and informal studies over the years. The questions researched are about originality in composition and sound, and the challenges that occur during the working period. Key words: Jazz, Improvisation, Composition, Music Production, Ensemble, Free, Ambient 2 (34) Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 4 1.2. Goal and Questions 5 1.3. Method 6 2. Pre-recorded material 2.1.” 2147” 6 2.2. ”SAKIN” 7 2.3. ”BLE” 8 2.4. The selected elements 9 3. The compositions 3.1. “Mobile” 10 3.1.2. The rehearsing process 11 3.2. “ONEHE-274” 12 3.2.2. The rehearsing process 14 3.3. “TURBULENCE” 15 3.3.2. The rehearsing process 16 3.4. Rehearsing with electronics only 17 4. Conclusion 19 5. Afterword 20 6. -

Amiina Puzzle Mp3, Flac, Wma

amiina Puzzle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Puzzle Country: Iceland Released: 2010 Style: Post Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1913 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1146 mb WMA version RAR size: 1116 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 195 Other Formats: RA WAV DMF AU MP2 AHX APE Tracklist Hide Credits Ásinn 1 5:31 Bass – Kjartan Sveinsson 2 Over And Again 3:39 What Are We Waiting For? 3 Bass – Kjartan SveinssonCello – Kristín LárusdóttirDouble Bass – Borgar MagnasonViola – 5:26 Guðrún Hrund HarðardóttirViolin – Bjarni Frímann Bjarnason, Ingrid Karlsdóttir 4 Púsl 6:13 In The Sun 5 4:16 Double Bass – Borgar Magnason 6 Mambó 4:56 Sicsak 7 Bass – Kjartan SveinssonCello – Kristín LárusdóttirDouble Bass – Borgar MagnasonViola – 6:51 Guðrún Hrund HarðardóttirViolin – Bjarni Frímann Bjarnason, Ingrid Karlsdóttir Thoka 8 Vocals [Additional] – Bryndís Nielsen, Inga Harðardóttir, Jóhann Ágúst Jóhannsson, Kjartan 3:55 Sveinsson, Sigtryggur Baldursson* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Sundlaugin Studio Recorded At – Grundarstíg Recorded At – Brekkustíg Recorded At – Granda Mixed At – Sundlaugin Studio Mastered At – Sterling Sound Credits Layout, Design – Sólrún Sumarliðadóttir Mastered By – Greg Calbi Mixed By – Birgir Jón Birgisson, amiina Music By, Performer – amiina Photography By [Photographs] – Lilja Birgisdóttir Notes Recorded in Sundlaugin, Grundarstíg, Brekkustíg, Granda and JL. Mixed in Sundlaugin Studio. Mastered at Sterling Sound, NYC. Digipak packaging The catalog# only appears on the CD matrix and sticker Track 4 was called "Þristurinn", track 7 "Tvisturinn" on their self-released record "Re Minore" Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: AMIINA5 *040415 Barcode (on sticker): 5 690351 110722 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Sound Of A shake 011, Puzzle (LP, shake 011, Amiina Handshake, Sound Of Germany 2011 SHAKE 011 Album) SHAKE 011 A Handshake Puzzle (CD, amiina5 amiina Amínamúsík Ehf. -

The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós' Heima and the Post

CURRENT ISSUE ARCHIVE ABOUT EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD CALL FOR PAPERS SUBMISSION GUIDELINES CONTACT Share This Article The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós’ Heima and the Post-Rock Elegy for Place ABOUT INTERFERENCE View As PDF By Lawson Fletcher Interference is a biannual online journal in association w ith the Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media (Gradcam). It is an open access forum on the role of sound in Abstract cultural practices, providing a trans- disciplinary platform for the presentation of research and practice in areas such as Amongst the ways in which it maps out the geographical imagination of place, music plays a unique acoustic ecology, sensory anthropology, role in the formation and reformation of spatial memories, connecting to and reviving alternative sonic arts, musicology, technology studies times and places latent within a particular environment. Post-rock epitomises this: understood as a and philosophy. The journal seeks to balance kind of negative space, the genre acts as an elegy for and symbolic reconstruction of the spatial its content betw een scholarly w riting, erasures of late capitalism. After outlining how post-rock’s accommodation of urban atmosphere accounts of creative practice, and an active into its sonic textures enables an ‘auditory drift’ that orients listeners to the city’s fragments, the engagement w ith current research topics in article’s first case study considers how formative Canadian post-rock acts develop this concrete audio culture. [ More ] practice into the musical staging of urban ruin. Turning to Sigur Rós, the article challenges the assumption that this Icelandic quartet’s music simply evokes the untouched natural beauty of their CALL FOR PAPERS homeland, through a critical reading of the 2007 tour documentary Heima. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: April 28, 2006 I, Kristín Jónína Taylor, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Musical Arts in: Piano Performance It is entitled: Northern Lights: Indigenous Icelandic Aspects of Jón Nordal´s Piano Concerto This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Steven J. Cahn Professor Frank Weinstock Professor Eugene Pridonoff Northern Lights: Indigenous Icelandic Aspects of Jón Nordal’s Piano Concerto A DMA Thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College–Conservatory of Music 28 December 2005 by Kristín Jónína Taylor 139 Indian Avenue Forest City, IA 50436 (641) 585-1017 [email protected] B.M., University of Missouri, Kansas City, 1997 M.M., University of Missouri, Kansas City, 1999 Committee Chair: ____________________________ Steven J. Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract This study investigates the influences, both domestic and foreign, on the composition of Jón Nordal´s Piano Concerto of 1956. The research question in this study is, “Are there elements that are identifiable from traditional Icelandic music in Nordal´s work?” By using set theory analysis, and by viewing the work from an extramusical vantage point, the research demonstrated a strong tendency towards an Icelandic voice. In addition, an argument for a symbiotic relationship between the domestic and foreign elements is demonstrable. i ii My appreciation to Dr. Steven J. Cahn at the University of Cincinnati College- Conservatory of Music for his kindness and patience in reading my thesis, and for his helpful comments and criticism. -

Writing Lilja: a Glance at Icelandic Music and Spirit J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Post-crash Iceland: opportunity, risk and reform Perspectives on Business and Economics 1-1-2011 Writing Lilja: A Glance at Icelandic Music and Spirit J. Casey Rule Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/perspectives-v29 Recommended Citation Rule, J. Casey, "Writing Lilja: A Glance at Icelandic Music and Spirit" (2011). Post-crash Iceland: opportunity, risk and reform. Paper 13. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/perspectives-v29/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Perspectives on Business and Economics at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Post-crash Iceland: opportunity, risk and reform by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITING LILJA: A GLANCE AT ICELANDIC MUSIC AND SPIRIT J. Casey Rule My cOntributiOn tO this jOurnal is rather aesthetic that is in nO way singularly Or sim - Out Of the Ordinary: instead Of writing a tradi - ply defined. MOre impOrtantly, the prOduct tiOnal article, I was asked tO cOmpOse a piece wOuld be inescapably inauthentic. Taking this Of music. As an aspiring cOmpOser, this was an apprOach wOuld be like standing in a fOrest OppOrtunity I cOuld nOt turn dOwn; hOwever, and explaining tO sOmeOne what a tree is by it presented sOme immediate challenges. PrOb - drawing a picture Of it. Naturally, the pieces that ably the mOst impOrtant and certainly the mOst are mOst infOrmative Of Icelandic music are vexing Of these was deciding hOw I cOuld actual pieces Of Icelandic music. -

Contents Welome 2 Conference Programme 4 Abstracts 24 Panels

17th Biennial Conference of IASPM | Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Challenging Orthodoxies | Gijón 2013 Contents Welome 2 Conference programme 4 Abstracts 24 Panels 133 iaspm2013.espora.es 1 17th Biennial Conference of IASPM | Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Challenging Orthodoxies | Gijón 2013 Dear IASPM Conference Delegates, Welcome to Gijón, and to the 17th biennial IASPM Conference “Bridge over Troubled Waters”, a conference with participants from all over the world with the aim of bridging a gap between disciplines, perspectives and cultural contexts. We have received more than 500 submissions, of which some 300 made it to the programme, together with four outstanding keynote speakers. This Conference consolidates the increasing participation of Spanish delegates in previous conferences since the creation of the Spanish branch of IASPM in 1999, and reinforces the presence of Popular Music Studies at the Spanish universities and research groups. The University of Oviedo is one of the pioneer institutions in the Study of Popular Music in Spain; since the late nineties, this field of study is constantly growing due to the efforts of scholars and students that approach this repertoire from an interdisciplinary perspective. As for the place that hosts the conference, Gijón is an industrial city with an important music scene. I wouldn´t call it the Spanish Liverpool, but some critics called it the Spanish Seattle because it was an important place for the development of “noise music” in Spain during the 1990s. The venue, Laboral, is an exponent of the architecture of the dictatorship. Finished in 1956, it was conceived as a school for war orphans to learn a trade and in 2007 it was remodeled to become a “city for culture”.