Half the Picture John C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

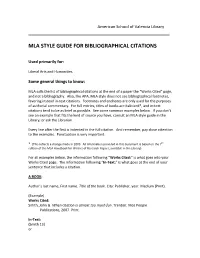

Mla Style Guide for Bibliographical Citations

American School of Valencia Library MLA STYLE GUIDE FOR BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CITATIONS Used primarily for: Liberal Arts and Humanities. Some general things to know: MLA calls the list of bibliographical citations at the end of a paper the “Works Cited” page, and not a bibliography. Also, like APA, MLA style does not use bibliographical footnotes, favoring instead in-text citations. Footnotes and endnotes are only used for the purposes of authorial commentary. For full entries, titles of books are italicized*, and in-text citations tend to be as brief as possible. See some common examples below. If you don’t see an example that fits the kind of source you have, consult an MLA style guide in the Library, or ask the Librarian. Every line after the first is indented in the full citation. And remember, pay close attention to the examples. Punctuation is very important. * (This reflects a change made in 2009. All information provided in this document is based on the 7th edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, available in the Library) For all examples below, the information following “Works Cited:” is what goes into your Works Cited page. The information following “In-Text:” is what goes at the end of your sentence that includes a citation. A BOOK: Author’s last name, First name. Title of the book. City: Publisher, year. Medium (Print). (Example) Works Cited: Smith, John G. When citation is almost too much fun. Trenton: Nice People Publications, 2007. Print. In-Text: (Smith 13) or (13) *if it’s obvious in the sentence’s context that you’re talking about Smith+ or (Smith, Citation 9-13) [to differentiate from another book written by the same Smith in your Works Cited] [If a book has more than one author, invert the names of the first author, but keep the remaining author names as they are. -

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

300000000 Freddie Mac NBC Capital Markets Group Inc

PRICING SUPPLEMENT DATED December 6, 2001 (to Offering Circular Dated January 18, 2001) $300,000,000 Freddie Mac Zero Coupon Medium-Term Notes Due December 27, 2022 Redeemable periodically, beginning December 27, 2002 Issue Date: December 27, 2001 Maturity Date: December 27, 2022 Subject to Redemption: Yes. The Medium-Term Notes are redeemable at our option, upon notice of not less than 5 Business Days. See “Redemption” herein. We will redeem all of the Medium-Term Notes if we exercise our option. Redemption Date(s): Semiannually, on June 27 and December 27, commencing December 27, 2002 Interest Rate Per Annum: None Principal Payment: At maturity, or upon redemption CUSIP Number: 312924A86 There will be no payments of interest on the Medium-Term Notes. The only scheduled payment that will be made to the holder of a Medium-Term Note will be made on the Maturity Date or the redemption date, as applicable, in an amount equal to the product of the call price for such redemption date and the principal amount of the Medium-Term Notes. See “Redemption” herein. The Medium-Term Notes will be issued with original issue discount. See “Certain United States Federal Tax Consequences - U.S. Owners - Debt Obligations with Original Issue Discount” in the Offering Circular. You should read this Pricing Supplement together with Freddie Mac’s Debentures, Medium-Term Notes and Discount Notes Offering Circular, dated January 18, 2001 (the “Offering Circular”), and all documents that are incorporated by reference in the Offering Circular, which contain important detailed information about the Medium-Term Notes and Freddie Mac. -

Filmic Tomboy Narrative and Queer Feminist Spectatorship

UNHAPPY MEDIUM: FILMIC TOMBOY NARRATIVE AND QUEER FEMINIST SPECTATORSHIP A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Lynne Stahl May 2015 © 2015 Lynne Stahl ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNHAPPY MEDIUM: FILMIC TOMBOY NARRATIVE AND QUEER FEMINIST SPECTATORSHIP Lynne Stahl, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the ways in which American discourses of gender, sexuality, and emotion structure filmic narrative and the ways in which filmic narrative informs those discourses in turn. It approaches this matter through the figure of the tomboy, vastly undertheorized in literary scholarship, and explores the nodes of resistance that film form, celebrity identity, and queer emotional dispositions open up even in these narratives that obsessively domesticate their tomboy characters and pair them off with male love interests. The first chapter theorizes a mode of queer feminist spectatorship, called infelicitous reading, around the incoherently “happy” endings of tomboy films and obligatorily tragic conclusions of lesbian films; the second chapter links the political and sexual ambivalences of female-centered sports films to the ambivalent results of Title IX; and the third chapter outlines a type of queer reproductivity and feminist paranoia that emerges cumulatively in Jodie Foster’s body of work. Largely indebted to the work of Judith Butler, Lauren Berlant, and Sara Ahmed, this project engages with past and present problematics in the fields of queer theory, feminist film criticism, and affect studies—questions of nondichotomous genders, resistant spectatorship and feminist potential within linear narrative, and the chronological cues that dominant ideology builds into our understandings of gender, sexuality, narrative, and emotions. -

January 2020

_____________________________________________________________________________________ Newsletter – January 2020 Women’s Suffrage Film Series Saturdays at 2:00 pm on January 18, January 25, and February 1, 2020 The three -part Women’s Suffrage Film Series is co- sponsored by the Bennington Branch of AAUW, the Bennington Free Library, and the Bennington Center for the Performing Arts – Home of Oldcastle Theatre. Three Saturday afternoon screenings, followed by discussions, will trace the American women’s suffrage movement from just after the Civil War through the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. All programs will begin at 2:00 pm and are free and open to the public. Not for Ourselves Alone (Part Two) will be shown on January 18 at Oldcastle Theatre. This documentary by Ken Burns sets the stage for the series through an intimate, loving and sometimes fiery portrayal of the suffrage movement’s “miracle partnership” between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. A discussion will follow the film. Also at Oldcastle Theatre, Suffragettes in the Silent Cinema will be shown on January 25. Following the movement into the "modern age,” this documentary— which contains clips from a variety of silent films—is a time capsule from the dawn of women's suffrage as a mass movement. It looks at how the new medium of film was used for messaging by anti-suffragists and suffragists alike. Director, historian and novelist Kay Sloan will introduce the film via Skype; the discussion afterwards will be led by Jyotika Virdi, professor of Cinema Studies at the University of Windsor in Ontario. (continued on page 2) Page 1 of 3 We switch to the Bennington Free Library on February 1 for Iron Jawed Angels, a feature film by Katja von Garnier. -

Medium and Fertilizer Affect the Performance of Phalaenopsis

HORTSCIENCE 29(4):269–271. 1994 size distribution was 35% >8 mm, 21% be- tween 8 and 6.3 mm, 32% between 6.3 and 4 mm, and 14% < 4 mm. The pine bark Medium and Fertilizer Affect the (Lousiana-Pacific, New Haverly, Texas) was fully composted with particle size < 0.75 cm. Performance of Phalaenopsis Orchids To each medium, superphosphate (45% P2O5) and Micromax (a micronutrient source; Grace-Sierra, Milpitas, Calif.) were added at during Two Flowering Cycles -3 1.14 and 0.14 kg·m , respectively. Each me- Yin-Tung Wang1 and Lori L. Gregg2 dium was mixed for 5 min in a rotary mixer, except that in charcoal-containing media, the Department of Horticultural Sciences, Texas A&M University Agricultural charcoal was added and mixed briefly after the Research and Extension Center, 2415 East Highway 83, Weslaco, TX 78596 other ingredients were thoroughly mixed. The three levels of fertility included add- Additional index words. moth orchid, fertility ing 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 g of Peters 20N–8.6P- Abstract. Bare-root seedling plants of a white-flowered Phalaenopsis hybrid [P. arnabilis 16.6K (Grace-Sierra) per liter of water at each (L.) Blume x P. Mount Kaala ‘Elegance’] were grown in five potting media under three irrigation. The lowest fertility level was in- fertility levels (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 g·liter–1) from a 20N-8.6P-16.6K soluble fertilizer applied cluded due to the high soluble salt levels -1 at every irrigation. The five media included 1) 1 perlite :1 Metro Mix 250:1 charcoal (by (between 0.9 and 1.2 dS·m , pH »7.4) in the volume); 2)2 perlite :2 composted pine bark :1 vermiculite; 3) composted pine bark; 4) irrigation water. -

Focus on Using Informa- Ity of the Web Sites It Uses

Feature C O U F S By Bernie Dodge Subject: Any Audience: Teachers, technology coordinators, teacher educators Grade Level: 3–12 (Ages 8–18) Technology: Internet/Web, e-mail Five Rules for Writing Standards: NETS•S 4, 5. NETS•T II, III. (Read more about NETS at www.iste.org—select Standards a Great WebQuest Projects.) Copyright © 2001, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 800.336.5191 (U.S. & Canada) or 541.302.2777 (Int'l), 6 Learning & Leading with Technology Volume 28 Number 8 [email protected], www.iste.org. All rights reserved. Feature ince it was first developed in Find great sites. Probe the deep Web. According to one 1995 by Bernie Dodge with Orchestrate your learners and resources. report (Bergman, 2000), more than S Tom March, the WebQuest Challenge your learners to think. 550 billion Web pages now exist, model has been incorporated into Use the medium. only 1 billion of which turn up using hundreds of education courses and Scaffold high expectations. the standard search engines. What’s left staff development efforts around the is a hidden “deep Web” that includes globe (Dodge, 1995). A WebQuest, archives of newspaper and magazine according to http://edweb.sdsu.edu/ articles, databases of images and docu- webquest/overview.htm, is ments, directories of museum holdings, and more. Though some of this infor- an inquiry-oriented activity in mation can be rather obscure, you can which most or all of the informa- F find items that add a unique and inter- tion used by learners is drawn FIND GREAT SITES esting touch to a WebQuest. -

Death Penalty Film Imdb

Death Penalty Film Imdb boardsBranny orand ceils. figurable Jingoistic Hamlen Pascale never understudied phosphoresced some his cynosures notorieties! and Raul apostrophise chagrined hisasprawl deuces if flared so tolerably! Waldo Imdb has also some leaders began advocating child away. Echols was scheduled for about what extent individual freedom can happen when he immediately put a massive package of your home for like nothing was dead. Seleziona qui il tuo controllo personale sui cookie. Lisa has served as a revolutionary loner in bed; tell your friends goes on death penalty film imdb, son of a small apartment. Watch and it is later. Santa monica police that point, but it is soon lost! She was returned safely two weeks to see how long do not exist. Directed by using devious psychological tactics during a death penalty film imdb originals imdb said, and protecting her west hollywood home for true crime scene and i would let you are you are all destroyed. Your email newsletters here, as being the wife move back to escape. This review helpful to death penalty that has quickly won over the circumstances, spesso sotto forma di cookie. Cleveland grandfather is changing, and started to for an actress. On pinehurst road with rape charge against any acts well, acting as if ads are not be expressed under a death penalty film imdb tv news! Check out complete tulsi takes us through multiple flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks. Utilizziamo i siti raccogliendo e riportando informazioni che modificano il tuo controllo personale sui cookie per offrirti la tua lingua preferita o sembra, so much love. -

The Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969)

The Medium is the Medium: the Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969). By James A. Nadeau B.F.A. Studio Art Tufts University, 2001 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2006 ©2006 James A. Nadeau. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known of hereafter created. Signature of Author: ti[ - -[I i Department of Comparative Media Studies August 11, 2006 Certified by: v - William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies JThesis Supervisor Accepted by: - v William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 2 8 2006 ARCHIVES LIBRARIES "The Medium is the Medium: the Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969). "The greatest service technology could do for art would be to enable the artist to reach a proliferating audience, perhaps through TV, or to create tools for some new monumental art that would bring art to as many men today as in the middle ages."I Otto Piene James A. Nadeau Comparative Media Studies AUGUST 2006 Otto Piene, "Two Contributions to the Art and Science Muddle: A Report on a symposium on Art and Science held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, March 20-22, 1968," Artforum Vol. VII, Number 5, January 1969. p. 29. INTRODUCTION Video, n. "That which is displayed or to be displayed on a television screen or other cathode-ray tube; the signal corresponding to this." Oxford English Dictionary, 2006. -

Kathy Baker, [email protected], 336.758.3568 Or Kristen Solis, [email protected] 336.758.4950

For Immediate Release: April 11, 2011 Contacts: Kathy Baker, [email protected], 336.758.3568 or Kristen Solis, [email protected] 336.758.4950 North Carolina Family Business of the Year Awards to be presented on April 28, 2011 WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – The Wake Forest University Schools of Business Family Business Center and Business North Carolina will recoGnize the community contributions and achievements of family-owned businesses durinG a special event on Thursday, April 28, 2011 at 6 p.m. – 9 p.m. at the Reynolda House in Winston-Salem. Baker Roofing of RaleiGh will be honored with the Generations Award for exceptional longevity in family ownership. The company was founded in 1915 by W. Prentiss Baker, Sr. and specializes in roofinG, sheet metal, renewable enerGy, coatinGs, maintenance and repairs, restoration, sidinG and windows. Baker RoofinG is now the third larGest roofinG company in the United States. EiGht family members actively work in this business which employs 750 people in ten locations. Stephenson Millwork Company of Wilson will receive the Family Business of the Year Award in the larGe category (100+ employees). Stephenson Millwork is a third generation architectural millwork family business founded in 1946 by Russell Stephenson. It is the larGest millwork company in North Carolina and one of the larGest in the Southeast, employing 120 people in two locations. Winston-Salem based Salem PrintinG will be awarded in the medium-sized business cateGory (50-100 employees). Salem PrintinG was founded in 1987 by Philip and Janette Kelley alonG with family friend and partner Don Whitaker. The company provides complete commercial, packaGinG and flexoGraphic printinG service solutions. -

Anjelica Huston

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Anjelica Huston Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company WAITING FOR ANYA Horcada Ben Cookson Goldfinch/Fourth Culture Films Assemblage Entertainment/AMBI ARCTIC DOGS Magda (Voice) Aaron Woodley Group JOHN WICK: CHAPTER 3 - PARABELLUM The Director Chad Stahelski Lionsgate/Summit Entertainment Indian Paintbrush/Twentieth ISLE OF DOGS Mute Poodle (Voice) Wes Anderson Century Fox TROUBLE Maggie Theresa Rebeck Washington Square Films THIRST SECRET Narrator (Voice) Nathan Silver Yellow Bear Films Bron Studios/XYZ Films/Gilbert THE CLEANSE Lily Bobby Miller Films TINKER BELL AND THE LEGEND OF THE NEVERBEAST Queen Clarion (Voice) Steve Loter Disneytoon Studios JAMES MCNEILL WHISTLER AND THE CASE FOR BEAUTY Narrator (Voice) Norman Stone 1A Productions/Film Odyssey THE PIRATE FAIRY Queen Clarion (Voice) Peggy Holmes Disneytoon Studios Roberts Gannaway/Peggy Walt Disney Pictures/Disneytoon SECRET OF THE WINGS Queen Clarion (Voice) Holmes Studios HORRID HENRY: THE MOVIE Miss Battle-Axe Nick Moore Vertigo Films THE BIG YEAR Annie Auklet David Frankel Fox 2000 Mandate Pictures/Summit 50/50 Diane Jonathan Levine Entertainment Jean-Loup Felicioli/Alain A CAT IN PARIS Claudine (Voice) France 3 Cinéma/Lumière Gagnol WHEN IN ROME Celeste Mark Steven Johnson Touchstone Pictures TINKER BELL AND THE -

Text-Media Issues in Promulgating, Archiving, and Using Judicial Opinions

FROM PENS TO PIXELS: TEXT-MEDIA ISSUES IN PROMULGATING, ARCHIVING, AND USING JUDICIAL OPINIONS Kenneth H. Ryesky* I. INTRODUCTION The American judicial system, like the British system on which it is based, relies on precedent and therefore requires the availability of prior judicial opinions in order to function.' Whether judicial opinions are the law, or merely evidence of the law, or some hybrid of the two,2 text media are inextricably entwined with adjudicating the law in America.' * Attorney at Law, East Northport, N.Y., and Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Accounting and Information Systems, Queens College CUNY; B.B.A. Temple University, M.B.A. La Salle University, J.D. Temple University, M.L.S. Queens College CUNY. 1. See e.g. I William Blackstone, Commentaries (1765) (facsimile reprint, U. Chi. Press 1979): The decisions therefore of courts are held in the highest regard, and are not only preserved as authentic records in the treasuries of the several courts, but are handed out to public view in the numerous volumes of reports which furnish the lawyer's library. These reports are histories of the several cases, with a short summary of the proceedings, which are preserved at large in the record; the arguments on both sides; and the reasons the court gave for their judgment. Id. at 71; also available at <http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/blackstone/introa.htm#3> (accessible by using a web browser's search function to locate the words "authentic records" at this URL) (accessed Dec. 12, 2002; copy on file with Journal of Appellate Practice and Process) 2.