Name: Ingemar Johansson Career Record: Click Alias: Ingo Nationality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tsnfiwvsimr TIRES Te«Gg?L

DUE TO NEIGHBORHOOD PRESSURE Tulloch, Aussie Mays Unable to Buy Terps Fly to Face " i-', j 5 '*¦ 1 ' '''''¦- r_ ?-‘1 San Francisco Home Wonder Horse, Tough Miami Battle By MERRELL WHITTLESEY burgh remaining on their SAN FRANCISCO. Nov. 14 want you. what's the good of Star Staff Correspondent schedule. |H (JP>. —Willie Mays’ attempt to buying,’’ Mays continued. MIAMI, Nov. 14—For the Coming to U. This comeback has placed / S. yester- buy a house here failed ’’Blittalk about a thing like second straight week Maryland the Hurricanes on the list of day Jjecause he is a Negro. this goes all over the world, SYDNEY, Australia, Nov. 14 is facing a predominantly eligibles P).—Tulloch, Australia’s for Jacksonville’s The spectacular, 27-year-old and it sure looks bad for our 0 1 new young team with a late-season Gator Bowl, providing, of of San ; country.” wonder horse which is being kick when the Terps meet course, centerflelder the Fran- greater they win their last three cisco Giants offered the $37,- Mays’ wife, Marghuerite, acclaimed as than the | Miami here tomorrow night. It games. quite as philosophical famous Pliar Lap. is ,being 500 asked by the owner for a ; wasn't bears out Coach Tommy Mont's Gator Bowl officials new house 175 Miraloma about It. “Down in Alabama readied foj a campaign in the earlier statement listed at States, ; that this Miami as one of nine teams un- drive, but was turned down where we come from,” she United with the ulti- year's schedule should have mate a der consideration. -

New York State Boxing Hall of Fame Announces Class of 2018

New York State Boxing Hall of Fame Announces Class of 2018 NEW YORK (January 10, 2018) – The New York State Boxing Hall of Fame (NYSBHOF) has announced its 23-member Class of 2018. The seventh annual NYSBHOF induction dinner will be held Sunday afternoon (12:30-5:30 p.m. ET), April 29, at Russo’s On The Bay in Howard Beach, New York. “This day is for all these inductees who worked so hard for our enjoyment,” NYSBHOF president Bob Duffy said, “and for what they did for New York State boxing.” Living boxers heading into the NYSBHOF include (Spring Valley) IBF Cruiserweight World Champion Al “Ice” Cole (35-16-3, 16 KOs), (Long Island) WBA light heavyweight Lou “Honey Boy” Del Valle (36-6-2, 22 KOs), (Central Islip) IBF Junior Welterweight World Champion Jake Rodriguez (28-8-2, 8 KOs), (Brooklyn) world lightweight title challenger Terrence Alli (52-15-2, 21 KOs), and (Buffalo) undefeated world-class heavyweight “Baby” Joe Mesi (36-0, 29 KOs). Posthumous participants being inducted are NBA & NYSAC World Featherweight Champion (Manhattan) Kid “Cuban Bon Bon” Chocolate (136-10-6, 51 KOs), (New York City) 20th century heavyweight James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett (11-4-3, 5 KOs), (Williamsburg) World Lightweight Champion Jack “The Napoleon of The Prize Ring” McAuliffe, (Kingston) WBC Super Lightweight Champion Billy Costello (40-2, 23 KOs), (Beacon) NYSAC Light Heavyweight World Champion Melio Bettina (83-14-3, 36 KOs), (Brooklyn/Yonkers) world-class middleweight Ralph “Tiger” Jones (52-32-5, 13 KOs) and (Port Washington) heavyweight contender Charley “The Bayonne Bomber” Norkus (33-19, 19 KOs). -

Boxing Edition

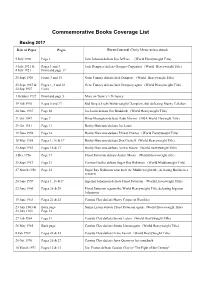

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

The History of the Pan American Games

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 The iH story of the Pan American Games. Curtis Ray Emery Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Emery, Curtis Ray, "The iH story of the Pan American Games." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/977 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—3376 microfilmed exactly as received EMERY, Curtis Ray, 1917- THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES. Louisiana State University, Ed.D., 1964 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education m The Department of Health, Physical, and Recreation Education by Curtis Ray Emery B. S. , Kansas State Teachers College, 1947 M. S ., Louisiana State University, 1948 M. Ed. , University of Arkansas, 1962 August, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Illustrations are not original copy. These pages tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the close co operation and assistance of many individuals who gave freely of their time. -

THE BELT IS BACK. the Story Behind the Return of the Hickok Belt Award

THE BELT IS BACK. THE STORY BEHIND THE RETURN OF THE HICKOK BELT AWARD. It’s the greatest comeback in sports the Hickok Belt Award was American history. Bigger than any MVP. Bigger than sports’ most coveted honor. Defining the a Lombardi. Bigger than a World Series careers of Koufax. Hogan. Palmer. Mantle. ring. Bigger than a Green Jacket. Bigger, Ali. And 21 other professional sports in fact, than all of them combined. legends. Join us as we count down to find out which of today’s legends will join them In 2012 the Hickok Belt Award returns. as the 2012 Hickok Belt Award winner. And for the first time in 36 years there will TO SEE THE FULL HICKOK BELT be an answer to the question, “Who’s the AWARD WINNERS PHOTO GALLERY, VISIT WWW.HICKOKBELT.COM best of the best in professional sports?” For 26 years, from 1950 to 1976, “Who’s the best of the best IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTs?” www.HickokBelt.com THE STORIED HIST OF THE A ORY WARD THAT MADE SPOR TS HIST The Hickok Belt Award was ORY. conceived as a way to honor Ray Sandy Koufax, Jim Brown, Mickey Mantle, and Alan Hickok’s father, Stephen Joe Namath and Arnold Palmer. Rae Hickok, an avid sportsman and The Legends of Sports’ Most An impressive list to be sure, but no more the entrepreneurial innovator behind the Prestigous Short List Hickok Manufacturing Company, once the impressive than each winner’s individual largest and most respected maker of men’s stories— to read each one and view video 1950 Phil Rizzuto Baseball 1951 Allie Reynolds Baseball belts and accessories in the world. -

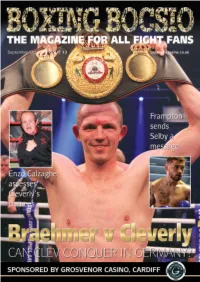

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

Fight Year Duration (Mins)

Fight Year Duration (mins) 1921 Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (23:10) 1921 23 1932 Max Schmeling vs Mickey Walker (23:17) 1932 23 1933 Primo Carnera vs Jack Sharkey-II (23:15) 1933 23 1933 Max Schmeling vs Max Baer (23:18) 1933 23 1934 Max Baer vs Primo Carnera (24:19) 1934 25 1936 Tony Canzoneri vs Jimmy McLarnin (19:11) 1936 20 1938 James J. Braddock vs Tommy Farr (20:00) 1938 20 1940 Joe Louis vs Arturo Godoy-I (23:09) 1940 23 1940 Max Baer vs Pat Comiskey (10:06) – 15 min 1940 10 1940 Max Baer vs Tony Galento (20:48) 1940 21 1941 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-I (23:46) 1941 24 1946 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-II (21:48) 1946 22 1950 Joe Louis vs Ezzard Charles (1:04:45) - 1HR 1950 65 version also available 1950 Sandy Saddler vs Charley Riley (47:21) 1950 47 1951 Rocky Marciano vs Rex Layne (17:10) 1951 17 1951 Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano (23:55) 1951 24 1951 Kid Gavilan vs Billy Graham-III (47:34) 1951 48 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Jake LaMotta-VI (47:30) 1951 47 1951 Harry “Kid” Matthews vs Danny Nardico (40:00) 1951 40 1951 Harry Matthews vs Bob Murphy (23:11) 1951 23 1951 Joe Louis vs Cesar Brion (43:32) 1951 44 1951 Joey Maxim vs Bob Murphy (47:07) 1951 47 1951 Ezzard Charles vs Joe Walcott-II & III (21:45) 1951 21 1951 Archie Moore vs Jimmy Bivins-V (22:48) 1951 23 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Randy Turpin-II (19:48) 1951 20 1952 Billy Graham vs Joey Giardello-II (22:53) 1952 23 1952 Jake LaMotta vs Eugene Hairston-II (41:15) 1952 41 1952 Rocky Graziano vs Chuck Davey (45:30) 1952 46 1952 Rocky Marciano vs Joe Walcott-I (47:13) 1952 -

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 13, 1929

rnmmmmtimiiifflmwm tMwwwiipiipwi!^^ 32 BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, NEW YORK, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13, 1929. Iowa Has Punished ows More Than Disciplining The Double-Fused Bomb—Which'li Explode It? By Ed Hughes Few Athletes Needed .0., Ere House Is Cleaned Despite Ruby's Punch -t • By GEORGE CVRRIE By ED HUGHES. io'.va( having cleaned house by simply taking a broom A double-fused knockout bomb, figuratively speaking, and sweeping her outstanding athletes out oi the locker will splutter and probably explode in the Garden ring tonight, room, cannot be accused of dodging the issue for which she Jimmy McLarnin, the Irish Thumper, and Ruby Goldstein, was suspended by the "Big Ten" when she insists upon much-thumped idol of the Ghetto, will meet* naming her own athletic director^ Not only has she dis- in a scheduled ten-rounder. The betting is TO$f__, Sbrl.and 7—5 on McLarnin, but the talk you year's basketball team apart, ail to prove the simon purity might jsay is almost at evens. McLarnin of her intentions. and Goldstein are two of the hardest hitting The Hawkeyes are thus in a position to demand rein welterweights that have appeared since the statement and, reinstated, to demand a follow up of the dangerous days of Joe Walcott, famed Bar- Carnegie Foundation report so lar<s>— badoes demon. as it concerns sister universities in) boys—ah, my friends, countrymen the "Big Ten" conference. Incidentally, destiny, with a sense of and New Yorkers, that is another the dramatic, decreed that the great col-, A fair indication of the drastic story! mopping up which Iowa has under One awaits the action of Iowa ored gladiator of other days should be a taken may t>e gathered from the with a hopeful but not expectant part of tonight's turnup. -

Collected by Staff

Collected by Staff Envelope sent from Gila River Relocation Center, sent by Henry Kondo to University of Southern California Student Union Store, stamped from Rivers Post Office 1 Collected by Staff Service Club ball invitation Markus Wheaton Pittsburgh Steelers replica jersey 2017.2.17 2017.2.16 2 Collected by Staff 2017.2.29 (FX1) San Francisco, Jan. 21 - With a title in mind - Top heavyweight contenders Eddie Machen, left, and Zora Folley, lower right, are shown here Boxing promotional poster featuring a 10 Round yesterday at the signing of contracts for a Heavyweight fight between Zora Folley and Big Al 12-round bout at the Cow Palace March 17. The Jones winner is expected to have a chance soon at the heavyweight crown now worn by Floyd Patterson. Seated between the two fighters is matchmaker 3 Collected by Staff Bennie Ford. Standing, left to right: Abe Acquisapace and Jim Pusateri, promoters, and Bill Swift, manager of Folley. (APWIREPHOTO) (b30400c1h) 1958 (LA12) Los Angeles, July 25--RADEMACHER (NY37) New York, March 21 - SHARING DAD'S HEADED DOWN--Zora Folley clips Pete CORNER - World heavyweight challenger Zora Rademacher with a smashing left to the jaw that Folley looks over at his son, Zora, Jr., as they share sent the former Olympic games champion to the a corner in a New York restaurant today. On the canvas for the first time, in the third round, of Folley menu is a title fight between the challenger their fight here tonight. Folley won by a knockout and Cassius Clay tomorrow night in New York in the fourth after Rademacher hit the canvas for City. -

Tough Jews: Fathers, Sons, and Gangster Dreams Why Should You Care?

Jewish Tough Guys Gangsters and Boxers From the 1880s to the 1980s Jews Are Smart When we picture a Jew the image that comes to mind for many people is a scientist like Albert Einstein Jews Are Successful Some people might picture Jacob Schiff, one of the wealthiest and most influential men in American history Shtarkers and Farbrekhers We should also remember that there were also Jews like Max Baer, the heavyweight Champion of the World in 1934 who killed a man in the ring, and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro, who “helped” settle labor disputes. Why Have They Been Forgotten? “The Jewish gangster has been forgotten because no one wants to remember him , because my grandmother won’t talk about him, because he is something to be ashamed of.” - Richard Cohen, Tough Jews: Fathers, Sons, and Gangster Dreams Why Should You Care? • Because this is part of OUR history. • Because it speaks to the immigrant experience, an experience that links us to many peoples across many times. • Because it is relevant today to understand the relationship of crime and combat to poverty and ostracism. Anti-Semitism In America • Beginning with Peter Stuyvesant in 1654, Jews were seen as "deceitful", "very repugnant", and "hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ". • In 1862, Ulysses S. Grant issues General Order 11, expelling all Jews from Tennessee, Mississippi and Kentucky. (Rescinded.) • In 1915, Leo Frank is lynched in Marietta, Georgia. • 1921 and 1924 quota laws are passed aimed at restricting the number of Jews entering America. • Jews were not the only target of these laws. -

Our Exclusive Rankings

#1 #10 #53 #14 #9 THE BIBLE OF BOXING + OUR EXCLUSIVE + RANKINGS P.40 + + ® #3 #13 #12 #26 #11 #8 #29 SO LONG CANELO BEST I TO A GEM s HBO FACED DAN GOOSSEN WHAT ALVAREZ’S HALL OF FAMER MADE THE BUSINESS ROBERTO DURAN JANUARY 2015 JANUARY MOVE MEANS FOR MORE FUN P.66 THE FUTURE P.70 REVEALS HIS TOP $8.95 OPPONENTS P.20 JANUARY 2015 70 What will be the impact of Canelo Alvarez’s decision to jump from FEATURES Showtime to HBO? 40 RING 100 76 TO THE POINT #1 #10 #53 #14 #9 THE BIBLE OF BOXING + OUR OUR ANNUAL RANKING OF THE REFS MUST BE JUDICIOUS WHEN EXCLUSIVE + RANKINGS P.40 WORLD’S BEST BOXERS PENALIZING BOXERS + + ® By David Greisman By Norm Frauenheim #3 #13 66 DAN GOOSSEN: 1949-2014 82 TRAGIC TURN THE LATE PROMOTER THE DEMISE OF HEAVYWEIGHT #12 #26 #11 #8 #29 SO LONG CANELO BEST I TO A GEM s HBO FACED DAN GOOSSEN WHAT ALVAREZ’S HALL OF FAMER MADE THE BUSINESS ROBERTO DURAN DREAMED BIG AND HAD FUN ALEJANDRO LAVORANTE 2015 JANUARY MOVE MEANS FOR MORE FUN P.66 THE FUTURE P.70 REVEALS HIS TOP $8.95 OPPONENTS P.20 By Steve Springer By Randy Roberts COVER PHOTOS: MAYWEATHER: ETHAN MILLER/ GETTY IMAGES; GOLOVKIN: ALEXIS CUAREZMA/GETTY 70 CANELO’S BIG MOVE IMAGES; KHAN/FROCH: SCOTT HEAVEY; ALVAREZ: CHRIS TROTMAN; PACQUIAO: JOHN GURZINSKI; HOW HIS JUMP TO HBO COTTO: RICK SCHULTZ: HOPKINS: ELSA/GOLDEN BOY; WILL IMPACT THE SPORT MAIDANA: RONALD MARTINEZ; DANNY GARCIA: AL BELLO; KLITSCHKO: DANIEL ROLAND/AFP/GETTY By Ron Borges IMAGES; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI DENIS POROY/GETTY IMAGES DENIS POROY/GETTY 1.15 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 6 RINGSIDE 7 OPENING SHOTS 12 COME OUT WRITING 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jabs and Straight Writes by Thomas Hauser 20 BEST I FACED: ROBERTO DURAN By Tom Gray 22 READY TO GRUMBLE By David Greisman 25 OUTSIDE THE ROPES By Brian Harty 27 PERFECT EXECUTION By Bernard Hopkins 32 RING RATINGS PACKAGE 86 LETTERS FROM EUROPE By Gareth A Davies 90 DOUGIEÕS MAILBAG By Doug Fischer 92 NEW FACES: JOSEPH DIAZ JR.