Louth Wetland Identification Survey Foss, Crushell, O'loughlin & Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit Louth Brochure

About County Louth • 1 hour commute from Dublin or Belfast; • Heritage county, steeped in history with outstanding archaeological features; • Internationally important and protected coastline with an unspoiled natural environment; • Blue flag beaches with picturesque coastal villages at Visit Louth Baltray, Annagassan, Clogherhead and Blackrock; • Foodie destination with award winning local produce, Land of Legends delicious fresh seafood, and an artisan food and drinks culture. and Full of Life • ‘sea louth’ scenic seafood trail captures what’s best about Co. Louth’s coastline; the stunning scenery and of course the finest seafood. Whether you visit the piers and see where the daily catch is landed, eat the freshest seafood in one of our restaurants or coastal food festivals, or admire the stunning lough views on the greenway, there is much to see, eat & admire on your trip to Co. Louth • Vibrant towns of Dundalk, Drogheda, Carlingford and Ardee with nationally-acclaimed arts, crafts, culture and festivals, museums and galleries, historic houses and gardens; • Easy access to adventure tourism, walking and cycling, equestrian and water activities, golf and angling; • Welcoming hospitable communities, proud of what Louth has to offer! Carlingford Tourist Office Old Railway Station, Carlingford Tel: +353 (0)42 9419692 [email protected] | [email protected] Drogheda Tourist Office The Tholsel, West St., Drogheda Tel: +353 (0)41 9872843 [email protected] Dundalk Tourist Office Market Square, Dundalk Tel: +353 (0)42 9352111 [email protected] Louth County Council, Dundalk, Co. Louth, Ireland Email: [email protected] Tel: +353 (0)42 9335457 Web: www.visitlouth.ie @VisitLouthIE @LouthTourism OLD MELLIFONT ABBEY Tullyallen, Drogheda, Co. -

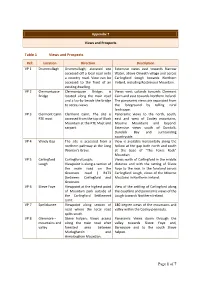

Appendix 11 Views and Prospects

Appendix 7 Views and Prospects Table 1 Views and Prospects Ref: Location Direction Description VP 1 Drummullagh Drummullagh; elevated site Extensive views east towards Narrow accessed off a local road onto Water, above Omeath village and across a country road. View can be Carlingford Lough towards Northern accessed to the front of an Ireland, including Rostrevour Mountain. existing dwelling. VP 2 Clermontpase Clermontpase Bridge; is Views west uplands towards Clermont Bridge located along the main road Cairn and east towards Northern Ireland. and a lay-by beside the bridge The panoramic views are separated from to access views. the foreground by rolling rural landscape. VP 3 Clermont Cairn Clermont Cairn; The site is Panoramic views to the north, south, RTE mast accessed from the top of Black east and west of Cooley mountains, Mountain at the RTE Mast and Mourne Mountains and beyond. carpark. Extensive views south of Dundalk, Dundalk Bay and surrounding countryside. VP 4 Windy Gap The site is accessed from a View is available horizontally along the northern pathway at the Long hollow at the gap both north and south Woman’s Grave. at the base of “The Foxes Rock” Mountian. VP 5 Carlingford Carlingford Lough; Views north of Carlingford in the middle Lough Viewpoint is along a section of distance and with the setting of Slieve the main road on the Foye to the rear. In the foreland across Greenore road ( R173 Carlingford Lough, views of the Mourne )between Carlingford and Moutains in Northern Ireland. Greenore. VP 6 Slieve Foye Viewpoint at the highest point View of the settling of Carlingford along of Mountain park outside of the coastline and panoramic views of the the Carlingford Settlement Lough towards Northern Ireland. -

Global Peatland Restoration Manual

Global Peatland Restoration Manual Martin Schumann & Hans Joosten Version April 18, 2008 Comments, additions, and ideas are very welcome to: [email protected] [email protected] Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, Greifswald University, Germany Introduction The following document presents a science based and practical guide to peatland restoration for policy makers and site managers. The work has relevance to all peatlands of the world but focuses on the four core regions of the UNEP-GEF project “Integrated Management of Peatlands for Biodiversity and Climate Change”: Indonesia, China, Western Siberia, and Europe. Chapter 1 “Characteristics, distribution, and types of peatlands” provides basic information on the characteristics, the distribution, and the most important types of mires and peatlands. Chapter 2 “Functions & impacts of damage” explains peatland functions and values. The impact of different forms of damage on these functions is explained and the possibilities of their restoration are reviewed. Chapter 3 “Planning for restoration” guides users through the process of objective setting. It gives assistance in questions of strategic and site management planning. Chapter 4 “Standard management approaches” describes techniques for practical peatland restoration that suit individual needs. Unless otherwise indicated, all statements are referenced in the IPS/IMCG book on Wise Use of Mires and Peatlands (Joosten & Clarke 2002), that is available under http://www.imcg.net/docum/wise.htm Contents 1 Characteristics, -

The Virginia Wetlands Report Vol. 12, No. 2

W&M ScholarWorks Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Wetlands Reports (CCRM) Summer 7-1-1997 The Virginia Wetlands Report Vol. 12, No. 2 Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccrmvawetlandreport Part of the Environmental Education Commons Recommended Citation Virginia Institute of Marine Science, "The Virginia Wetlands Report Vol. 12, No. 2" (1997). Virginia Wetlands Reports. 28. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccrmvawetlandreport/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Coastal Resources Management (CCRM) at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Virginia Wetlands Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Summer 1997 TheThe VirginiaVirginia Vol. 12, No. 2 WetlandsWetlands ReportReport Wetlands Mitigation Banks: Creating Big Wetlands to Compensate for Many Small Losses Carl Hershner etlands mitigation banking is a acres each year. When you realize that wetland if at all possible. Relocating relatively new tool for wetlands new tidal wetlands are not appearing development on a parcel of land, or managers.W It is finding increasing naturally at a rate anywhere close to redesigning a project can often pre- application in the struggle to achieve a the rate of loss caused by man and serve the existing resource. When “no net loss” goal for our remaining nature, this “preventable” loss becomes avoidance is not possible, minimizing wetland resources. The concept of a concern. the area of impact is always the second creating wetlands and thus establish- The problem confronting resource objective. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Turbary Restoration Meets Variable Success: Does Landscape Structure Force Colonization Success of Wetland Plants?

RESEARCH ARTICLE Turbary Restoration Meets Variable Success: Does Landscape Structure Force Colonization Success of Wetland Plants? Boudewijn Beltman,1,2 NancyQ.A.Omtzigt,3 and Jan E. Vermaat3 Abstract of ponds in the complex, the SW orientation of ditches in these complexes and pH, and transparency of the water. Peat ponds have been restored widely in the Netherlands Age of the ponds (1–9 years), area of open water (8–42%), to enhance the available habitat for species-rich plant and shoreline density (13–43 km/km2 in the complex) did communities that characterize the early succession stages not contribute significantly to colonization success. Separa- toward land. Colonization success of 33 target aquatic tion of the effect of a species-rich surrounding landscape, species has been quantified in eight complexes of new the possibility to disperse through that landscape, the spa- ponds. It has been related to the lay-out of these ponds, the tial lay-out of the complex and transparency of the water structure of the surrounding landscape, (historic) preva- were precluded by the strong covariance along the first PC. lence of source populations within the complex and within a Probably all three are independently important. It is spec- perimeter of 10 km, and pond water quality. Colonization ulated that diel migration by waterfowl may be responsible success was variable: between 6 and 26 target species had for the dispersal of plant propagules to the pond complex, reached the complexes in 1998. This success was coupled whereas within-complex dispersal to establishment sites is to the first principal component (PC) in a principal compo- enhanced by wind and water movement. -

National Peatlands Strategy

NATIONAL PEATLANDS STRATEGY 2015 National Parks & Wildlife Service 7 Ely Place, Dublin 2, D02 TW98, Ireland t: +353-1-888 3242 e: [email protected] w: www.npws.ie Main Cover photograph: Derrinea Bog, Co. Roscommon Photographs courtesy of: NPWS, Bord na Móna, Coillte, RPS, Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, National Library of Ireland, Friends of the Irish Environment and the IPCC. MANAGING IRELAND’S PEATLANDS A National Peatlands Strategy 2015 Roundstone Bog, Co. Galway CONTENTS PART 1 PART 3 1 INTRODUCTION 004 6 IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING 060 1.1 Peatlands in Ireland 005 1.2 Protected Peatlands in Ireland 007 APPENDICES 2 THE CHANGING VIEW APPENDIX 1 OF IRISH PEATLANDS 008 SUMMARY OF PRINCIPLES 2.1 A New Understanding 009 AND ACTIONS 062 2.2 Seeking Balance between Traditional and Hidden Values 009 2.3 Turf cutting controversy – APPENDIX 2 a catalyst for change 011 GLOSSARY 070 2.4 The Way Forward 013 APPENDIX 3 PART 2 EU DIRECTIVES REFERRED TO IN THE STRATEGY 076 3 DEVELOPMENT OF THE STRATEGY 014 APPENDIX 4 4 VISION AND VALUES 018 LINKS & FURTHER INFORMATION 080 5 MANAGING OUR PEATLANDS: PRINCIPLES, POLICIES AND ACTIONS 024 5.1 Overview 024 5.2 Existing Uses 025 5.3 Peatlands and Climate Change 034 5.4 Air Quality 036 5.5 Protected Peatlands Sites 037 5.6 Peatlands outside Protected Sites 045 5.7 Responsible Exploitation 048 5.8 Restoration & Rehabilitation of Non-Designated Sites 050 5.9 Water Quality, Water Framework Directive and Flooding 050 5.10 Public Awareness & Education 055 5.11 Tourism & Recreational Use 058 5.12 Unauthorised Dumping 059 5.13 Research 059 PART 1 004 1. -

Peat Places Peat Today

Rathlin Island Peat places Tievebulliagh Carrick-a-rede The Glens of Antrim contain Garron Plateau many places where peat can The Garron Plateau is the biggest area of This upland area contains shallow peat. be found. The map highlights Knocklayde Ballintoy intact blanket bog on the east coast of Ireland. A rare rock known as porcellanite was peat places to explore. The site is rich with varieties of plants and wildlife. harvested here during the stone age and exported throughout Europe. Garron Plateau has undergone an extensive restoration project. Ballycastle Fairhead Special peat places Access from Cargan village, 10 miles north of Moyle Way Areas of Outstanding Ballymena on the Glenravel Road (A43) and eight Natural Beauty (AONB) miles south of Cushendall. Car parking is available at Dungonnell Dam, near Cargan village. Tow River Carey River Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) Glentasie Ballycastle Ramsar Wetland Sites of international importance Forest Special Protection Areas (SPA) Glenmakeeran River Glenshesk River Glenshesk Slieveanorra & Croaghan Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) Ballypatrick Moyle Way Forest National Nature Reserves (NNR) View from Glenaan Slieveanorra and Croaghan is an important Glenshesk Cregagh area of largely intact blanket bog. Slieveanorra Peat Areas Mountain shows the different stages in the Wood View from Tievebulliagh Armoy Non Peat Areas formation, erosion and regeneration of peat. Breen Cushendun Garron Plateau Ronan's Way AONB boundary line A variety of plants and upland birds can be Wood spotted, as can the common lizard. Main Roads Croaghan Breen Mountain Slieveanorra was the site of the Battle Glendun Forest Walk Glencorp Walking Routes Through Peatland of Orra in 1583. -

List of Irish Mountain Passes

List of Irish Mountain Passes The following document is a list of mountain passes and similar features extracted from the gazetteer, Irish Landscape Names. Please consult the full document (also available at Mountain Views) for the abbreviations of sources, symbols and conventions adopted. The list was compiled during the month of June 2020 and comprises more than eighty Irish passes and cols, including both vehicular passes and pedestrian saddles. There were thousands of features that could have been included, but since I intended this as part of a gazetteer of place-names in the Irish mountain landscape, I had to be selective and decided to focus on those which have names and are of importance to walkers, either as a starting point for a route or as a way of accessing summits. Some heights are approximate due to the lack of a spot height on maps. Certain features have not been categorised as passes, such as Barnesmore Gap, Doo Lough Pass and Ballaghaneary because they did not fulfil geographical criteria for various reasons which are explained under the entry for the individual feature. They have, however, been included in the list as important features in the mountain landscape. Paul Tempan, July 2020 Anglicised Name Irish Name Irish Name, Source and Notes on Feature and Place-Name Range / County Grid Ref. Heig OSI Meaning Region ht Disco very Map Sheet Ballaghbeama Bealach Béime Ir. Bealach Béime Ballaghbeama is one of Ireland’s wildest passes. It is Dunkerron Kerry V754 781 260 78 (pass, motor) [logainm.ie], ‘pass of the extremely steep on both sides, with barely any level Mountains ground to park a car at the summit. -

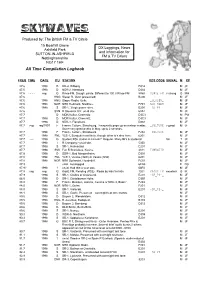

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

The Balance of Water -Present and Future

J!15met The Balance of Water - Present and Future moisture laden winds p e.t. pep e.t. p • p = precipitation e = evaporation l.f. = throughflow pe "" percolation e.t. - evapotranspiration Proceedings of AGMET Group (Ireland) and Agricultural Group o/the Royal Meteorological Society (UK) Conference Trinity College Dublin, September 7 - 9, 1994 General Editors: T. Keane and E. Daly Published by the AGMETGroup do Meteorological Service Glasnevin Hill Dublin 9 Copyright © the authors 1994 ISBN 0 95115513 X Cover: Water Balance diagram by kind permission: from Geomorphology and Hydrology by R ] Small, Longman Modular Geography Series Foreword Considerable reliance is placed on climatological and hydrological data for a wide range of water balance studies. The accuracy and archival status of the input data frequently concern hydrologists and agriculturals, who also ask what confidence can be attached to estimates of the different components. Apart from the reliability of instrumentation, the limitations of point measurement or estimation by fonnula, further difficulties arise from the specification of soil characteristics, effects of farming practices, distance from sea, altitude, and indeed from the method of spatialization of the data. This Dublin Conference sets out to review the research and progress of recent decades, address some of the current issues and indicate the likelihood of more accurate specification and determination of the parameters: precipitation, evaporation! evapotranspiration and run-off. The measurement and application of the water balance is central to the study of hydrology. A breath of scholarship together with the most recent research are brought to bear in the following papers presented at the Conference. -

Irish Hill and Mountain Names

Irish Hill and Mountain Names The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list where Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one more comprehensive. shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. Extensive revision these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed and extra data has been accepted from many MV contributors including Simon and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are Stewart, Brian Ringland, Paul Donnelly, John FitzGerald, Denise Jacques, Colin adopted here in all other cases.