The Transformation of Female Slave Subject To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slavery in America: the Montgomery Slave Trade

Slavery In America The Montgomery Trade Slave 1 2 In 2013, with support from the Black Heritage Council, the Equal Justice Initiative erected three markers in downtown Montgomery documenting the city’s prominent role in the 19th century Domestic Slave Trade. The Montgomery Trade Slave Slavery In America 4 CONTENTS The Montgomery Trade Slave 6 Slavery In America INTRODUCTION SLAVERY IN AMERICA 8 Inventing Racial Inferiority: How American Slavery Was Different 12 Religion and Slavery 14 The Lives and Fears of America’s Enslaved People 15 The Domestic Slave Trade in America 23 The Economics of Enslavement 24–25 MONTGOMERY SLAVE TRADE 31 Montgomery’s Particularly Brutal Slave Trading Practices 38 Kidnapping and Enslavement of Free African Americans 39 Separation of Families 40 Separated by Slavery: The Trauma of Losing Family 42–43 Exploitative Local Slave Trading Practices 44 “To Be Sold At Auction” 44–45 Sexual Exploitation of Enslaved People 46 Resistance through Revolt, Escape, and Survival 48–49 5 THE POST SLAVERY EXPERIENCE 50 The Abolitionist Movement 52–53 After Slavery: Post-Emancipation in Alabama 55 1901 Alabama Constitution 57 Reconstruction and Beyond in Montgomery 60 Post-War Throughout the South: Racism Through Politics and Violence 64 A NATIONAL LEGACY: 67 OUR COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF SLAVERY, WAR, AND RACE Reviving the Confederacy in Alabama and Beyond 70 CONCLUSION 76 Notes 80 Acknowledgments 87 6 INTRODUCTION Beginning in the sixteenth century, millions of African people The Montgomery Trade Slave were kidnapped, enslaved, and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas under horrific conditions that frequently resulted in starvation and death. -

SELF-FLAGELLATION in the EARLY MODERN ERA Patrick

SELF-FLAGELLATION IN THE EARLY MODERN ERA Patrick Vandermeersch Self-fl agellation is often understood as self-punishment. History teaches us, however, that the same physical act has taken various psychologi- cal meanings. As a mass movement in the fourteenth century, it was primarily seen as an act of protest whereby the fl agellants rejected the spiritual authority and sacramental power of the clergy. In the sixteenth century, fl agellation came to be associated with self-control, and a new term was coined in order to designate it: ‘discipline’. Curiously, in some religious orders this shift was accompanied by a change in focus: rather than the shoulders or back, the buttocks were to be whipped instead. A great controversy immediately arose but was silenced when the possible sexual meaning of fl agellation was realized – or should we say, constructed? My hypothesis is that the change in both the name and the way fl agellation was performed indicates the emergence of a new type of modern subjectivity. I will suggest, furthermore, that this requires a further elaboration of Norbert Elias’s theory of the ‘civiliz- ing process’. A Brief Overview of the History of Flagellation1 Let us start with the origins of religious self-fl agellation. Although there were many ascetic practices in the monasteries at the time of the desert fathers, self-fl agellation does not seem to have been among them. With- out doubt many extraordinary rituals were performed. Extreme degrees 1 The following historical account summarizes the more detailed historical research presented in my La chair de la passion. -

The Middle Passage MAP by Patagonia Routes SLAVE TRADING MARK ANDERSON MOORE Malvina (Falkland Is.) REGIONS Atlantic Slave Trade

Arctic Ocean Greenland Arctic Ocean ARCTIC CIRCLE Iceland Norway Sweden Finland B udson ay H North North Scotland Sea Denmark Moscow Labrador England Ireland Prussia British North A Atlantic Russian Empire mer London German ica Paris States Kiev OREGON Newfoundland Asia TERRITORY Quebec Ocean Montreal Austria Bay of France Vt. Me. Nova Scotia Biscay Italy C NY NH “TRIANGULAR TRADE” Black Sea a Mass. Rome Ottoman sp ia Pa. RI n LOUISIANA Oh. Conn. Portugal Madrid Empire Il. In. NJ United States S TERRITORY e Spain a Va. Del. Ky. Md. Azores Is. Tn. NC by 1820 M In TUNIS edi dian Terr. O terra Persia SC C nean S Ms. C ea Al. Madeira O Ga. R ALGIERS La. O M Cairo P Fla. Canary Is. er EGYPT sia n G Bahama Is. ulf Mexico Havana WESTERN SUDAN R. R e Mecca Mexico West Indies dle Pa d Cuba Mid ssag Nile S City he e e T a Arabia Haiti Timbuktu Vera Jamaica Puerto Rico Cruz Guadeloupe Cape Verde Is. Martinique SENEGAMBIA Niger Africa Arabian Central America Barbados Cape Verde R. Sea Portobelo Trinidad Caracas SIERRA ETHIOPIA Stabroek (Georgetown) LEONE GUINEA Paramaribo Cayenne BIGHT Bogotá WINDWARD GOLD OF BIGHT COAST COAST BENIN Mogadishu Galapagos Is. SL OF Quito Colombia AV BIAFRA Barro do Rio E T Negro RAD Belé m Fortaleza ING REGIONS CONGO Paita Indian Brazil Recife Trujillo Ocean Peru ANGOLA Lima Salvador La Plata ambezi La Paz Z R. Chuquisaca MOZAMBIQUE South America São Paulo Rio de Janeiro From The Way We Lived in North Carolina © 2003 The University of North Carolina Press Madagascar La Serena Santos Easter I. -

Image Credits, the Making of African

THE MAKING OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY: VOL. I, 1500-1865 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 IMAGE CREDITS Items listed in chronological order within each repository. ALABAMA DEPT. of ARCHIVES AND HISTORY. Montgomery, Alabama. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Physical and Political Map of the Southern Division of the United States, map, Boston: William C. Woodbridge, 1843; adapted to Woodbridges Geography, 1845; map database B-315, filename: se1845q.sid. Digital image courtesy of Alabama Maps, University of Alabama. ALLPORT LIBRARY AND MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS. State Library of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmania (Australia). WEBSITE Reproduced by permission of the Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office. —Mary Morton Allport, Comet of March 1843, Seen from Aldridge Lodge, V. D. Land [Tasmania], lithograph, ca. 1843. AUTAS001136168184. AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM. Lowell, Massachusetts. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Wooden snap reel, 19th-century, unknown maker, color photograph. 1970.14.6. ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. WEBSITE In the public domain; reproduced courtesy of Archives of Ontario. —Letter from S. Wickham in Oswego, NY, to D. B. Stevenson in Canada, 12 October 1850. —Park House, Colchester, South, Ontario, Canada, refuge for fugitive slaves, photograph ca. 1950. Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F2076-16-6. —Voice of the Fugitive, front page image, masthead, 12 March 1854. F 2076-16-935. —Unidentified black family, tintype, n.d., possibly 1850s; Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F 2076-16-4-8. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. Wilmore, Kentucky. Permission requests submitted. –“Slaves being sold at public auction,” illustration in Thomas Lewis Johnson, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or The Story of My Life in Three Continents, 1909, p. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

Human Trafficking: Issues Beyond Criminalization

IA SCIEN M T E IA D R A V C M A PONTIFICIAE ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARVM SOCIALIVM ACTA 20 S A O I C C I I F A I T L I N V M O P Human Trafficking: Issues Beyond Criminalization The Proceedings of the 20th Plenary Session 17-21 April 2015 Edited by Margaret S. Archer | Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo Libreria Editrice Vaticana • Vatican City 2016 Human Trafficking: Issues Beyond Criminalization The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences Acta 20 The Proceedings of the 20th Plenary Session Human Trafficking: Issues Beyond Criminalization 17-21 April 2015 Edited by Margaret S. Archer Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo IA SCIE M NT E IA D R A V C M A S A I O C C I F I I A T L I N V M O P LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA • VATICAN CITY 2016 The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences Casina Pio IV, 00120 Vatican City Tel: +39 0669881441 • Fax: +39 0669885218 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.pass.va The opinions expressed with absolute freedom during the presentation of the papers of this meeting, although published by the Academy, represent only the points of view of the participants and not those of the Academy. ISBN 978-88-86726-32-0 © Copyright 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, pho- tocopying or otherwise without the expressed written permission of the publisher. THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA VATICAN CITY In recent years, the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, thanks to the efforts of its President, its Chancellor and a num- ber of prestigious external collaborators – to whom I offer my heartfelt thanks – has engaged in important activities in defence of human dignity and freedom in our day. -

Who Is Afro-Latin@? Examining the Social Construction of Race and Négritude in Latin America and the Caribbean

Social Education 81(1), pp 37–42 ©2017 National Council for the Social Studies Teaching and Learning African American History Who is Afro-Latin@? Examining the Social Construction of Race and Négritude in Latin America and the Caribbean Christopher L. Busey and Bárbara C. Cruz By the 1930s the négritude ideological movement, which fostered a pride and conscious- The rejection of négritude is not a ness of African heritage, gained prominence and acceptance among black intellectuals phenomenon unique to the Dominican in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. While embraced by many, some of African Republic, as many Latin American coun- descent rejected the philosophy, despite evident historical and cultural markers. Such tries and their respective social and polit- was the case of Rafael Trujillo, who had assumed power in the Dominican Republic ical institutions grapple with issues of in 1930. Trujillo, a dark-skinned Dominican whose grandmother was Haitian, used race and racism.5 For example, in Mexico, light-colored pancake make-up to appear whiter. He literally had his family history African descended Mexicans are socially rewritten and “whitewashed,” once he took power of the island nation. Beyond efforts isolated and negatively depicted in main- to alter his personal appearance and recast his own history, Trujillo also took extreme stream media, while socio-politically, for measures to erase blackness in Dominican society during his 31 years of dictatorial the first time in the country’s history the rule. On a national level, Trujillo promoted -

Resistance, Language and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks History: Faculty Publications History Summer 2016 The tE ymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/hst_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Pryor, Elizabeth Stordeur, "The tE ymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North" (2016). History: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/hst_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Etymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor Journal of the Early Republic, Volume 36, Number 2, Summer 2016, pp. 203-245 (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jer.2016.0028 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/620987 Access provided by Smith College Libraries (5 May 2017 18:29 GMT) The Etymology of Nigger Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North ELIZABETH STORDEUR PRYOR In 1837, Hosea Easton, a black minister from Hartford, Connecticut, was one of the earliest black intellectuals to write about the word ‘‘nigger.’’ In several pages, he documented how it was an omni- present refrain in the streets of the antebellum North, used by whites to terrorize ‘‘colored travelers,’’ a term that elite African Americans with the financial ability and personal inclination to travel used to describe themselves. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

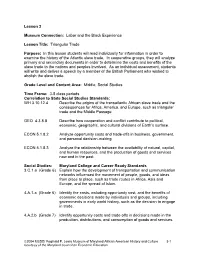

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

Abolition in Context: the Historical Background of the Campaign for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Abolition in context: the historical background of the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade Jeffrey HOPES Université du Mans The abolition of the slave trade by the British Parliament in 1807 was one of a series of legislative measures which led progressively to the abandonment of the slave economy in British held territories, culminating in the abolition of the legal framework of slavery in 1833 and in 1838 when the apprenticeship system was ended.1 The whole process whereby first the slave trade and then slavery itself were abolished can only be understood if all the different contexts, economic, military, political, ideological, cultural and social in which it took place are taken into account. The constant inter-connection of these contexts precludes any simple reliance on single explanations for the abolition of the slave trade, however tempting such explanations may be. In briefly summarising the nature of this multiple contextualisation, I do not wish to enter the on-going and fraught debate on the reasons for the abolition of the slave trade but simply to present it as a multi-faceted question, one which, like so many historical events, takes on a different appearance according to the position – in time and space – from which we approach it. Abolition and us In this respect, the first context which needs to be mentioned is that of our own relationship to the issue of slavery. The bicentenary of abolition in 2007 has seen the publication of a flood of articles, books, exhibitions and radio and television programmes in Britain and abroad. -

The Politics of Slavery and Human Trafficking (POLS4046 and POLS7051)

The Politics of Slavery and Human Trafficking (POLS4046 and POLS7051) Dr Joel Quirk Department of Political Studies Page 1 of 32 Course Information Contact Details The best way of getting in contact is through email at [email protected] . Bookings should normally take place between 2pm and 5pm on Wednesdays (designated office hours). Please make use of email to arrange bookings, rather than simply showing up, as students who have made bookings will be seen ahead of students who do not have bookings. The relevant office is CB32E. Time and Venue Thursday, 2pm to 5pm, Room 32. Course Aims & Objectives It is commonly assumed that slavery came to an end in the nineteenth century. While slavery in the Americas officially ended in 1888, millions of slaves remained in bondage across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East well into the first half of the twentieth century. Wherever laws against slavery were introduced, governments found ways of continuing similar forms of coercion and exploitation, such as forced, bonded and indentured labour. Every country in the world has now abolished slavery, yet tens of millions of people continue to find themselves subject to various forms of human bondage. In order to properly understand why and how slavery continues to be a problem in the world today, it is necessary to first take into account the relationship between the history of slavery and abolition and more recent practices and problems. Accordingly, this course begins with an introduction to the key features of historical slave systems, paying particular attention to slavery and abolition in Africa and the Americas from the sixteenth century onwards. -

Reflections on the Slave Trade and Impact on Latin American Culture

Unit Title: Reflections on the Slave Trade and Impact on Latin American Culture Author: Colleen Devine Atlanta Charter Middle School 6th grade Humanities 2-week unit Unit Summary: In this mini-unit, students will research and teach each other about European conquest and colonization in Latin America. They will learn about and reflect on the trans- Atlantic slave trade. They will analyze primary source documents from the slave trade by conducting research using the online Slave Voyages Database, reading slave narratives and viewing primary source paintings and photographs. They will reflect on the influence of African culture in Latin America as a result of the slave trade. Finally, they will write a slave perspective narrative, applying their knowledge of all of the above. Established Goals: Georgia Performance Standards: GA SS6H1: The student will describe the impact of European contact on Latin America. a. Describe the encounter and consequences of the conflict between the Spanish and the Aztecs and Incas and the roles of Cortes, Montezuma, Pizarro, and Atahualpa. b. Explain the impact of the Columbian Exchange on Latin America and Europe in terms of the decline of the indigenous population, agricultural change, and the introduction of the horse. GA SS6H2: The student will describe the influence of African slavery on the development of the Americas. Enduring Understandings: Students will be able to describe the impact of European contact on Latin America. Students will be able to define the African slave trade and describe the impact it had on Latin America. Students will reflect on the experiences of slaves in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.