Excavation of Post-Built Roundhouses and a Circular Ditched Enclosure at Kiltaraglen, Portree, Isle of Skye, 2006–07

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER October 2015

NEWSLETTER October 2015 Dates for your diary MAD evenings Tuesdays 7.30 - 9.30 pm at Strathpeffer Community Centre 17th November Northern Picts - Candy Hatherley of Aberdeen University 8th December A pot pourri of NOSAS activity 19th January 2016 Rock Art – Phase 2 John Wombell 16th February 15th March Bobbin Mills - Joanna Gilliat Winter walks Thursday 5th November Pictish Easter Ross with soup and sandwiches in Balintore - David Findlay Friday 4th December Slochd to Sluggan Bridge: military roads and other sites with afternoon tea - Meryl Marshall Saturday 9th January 2016 Roland Spencer-Jones Thursday 4th February Caledonian canal and Craig Phadrig Fort- Bob & Rosemary Jones Saturday 5th March Sat 9th April Brochs around Brora - Anne Coombs Training Sunday 8 November 2 - 4 pm at Tarradale House Pottery identification course (beginners repeated) - Eric Grant 1 Archaeology Scotland Summer School, May 2015 The Archaeology Scotland Summer School for 2015 covered Kilmartin and North Knapdale. The group stayed in Inveraray and included a number of NOSAS members who enjoyed the usual well researched sites and excellent evening talks. The first site was a Neolithic chambered cairn in Crarae Gardens. This cairn was excavated in the 1950s when it was discovered to contain inhumations and cremation burials. The chamber is divided into three sections by two septal slabs with the largest section at the rear. The next site was Arichonan township which overlooks Caol Scotnish, an inlet of Loch Sween, and which was cleared in 1848 though there were still some households listed in the 1851 census. Chambered cairn Marion Ruscoe Later maps indicate some roofed buildings as late as 1898. -

5 Years on Ice Age Europe Network Celebrates – Page 5

network of heritage sites Magazine Issue 2 aPriL 2018 neanderthal rock art Latest research from spanish caves – page 6 Underground theatre British cave balances performances with conservation – page 16 Caves with ice age art get UnesCo Label germany’s swabian Jura awarded world heritage status – page 40 5 Years On ice age europe network celebrates – page 5 tewww.ice-age-europe.euLLING the STORY of iCe AGE PeoPLe in eUROPe anD eXPL ORING PLEISTOCene CULtURAL HERITAGE IntrOductIOn network of heritage sites welcome to the second edition of the ice age europe magazine! Ice Age europe Magazine – issue 2/2018 issn 25684353 after the successful launch last year we are happy to present editorial board the new issue, which is again brimming with exciting contri katrin hieke, gerdChristian weniger, nick Powe butions. the magazine showcases the many activities taking Publication editing place in research and conservation, exhibition, education and katrin hieke communication at each of the ice age europe member sites. Layout and design Brightsea Creative, exeter, Uk; in addition, we are pleased to present two special guest Beate tebartz grafik Design, Düsseldorf, germany contributions: the first by Paul Pettitt, University of Durham, cover photo gives a brief overview of a groundbreaking discovery, which fashionable little sapiens © fumane Cave proved in february 2018 that the neanderthals were the first Inside front cover photo cave artists before modern humans. the second by nuria sanz, water bird – hohle fels © urmu, director of UnesCo in Mexico and general coordi nator of the Photo: burkert ideenreich heaDs programme, reports on the new initiative for a serial transnational nomination of neanderthal sites as world heritage, for which this network laid the foundation. -

South Skye Web.Indd

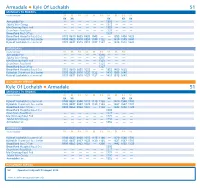

Armadale G Kyle Of Lochalsh 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Armadale Pier — — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 0935 1045 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 0950 1100 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 0957 1107 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 SATURDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 Armadale Pier — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 1005 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 1020 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 1027 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle Of Lochalsh G Armadale 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0740 0832 0900 1015 1115 1138 — 1420 1540 1700 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0745 0837 0907 1022 1120 1143 — 1427 1547 1707 Broadford Post Offi ce 0800 0852 0922 1037 — 1158 — 1442 1602 1722 Broadford Hospital Road End — — — — — — 1205 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1217 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1222 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1230 — — — Armadale Pier — — — — — — -

PE1591/M: Scottish Ambulance Service Letter of 28 October 2016

PE1591/M Scottish Ambulance Service Letter of 28 October 2016 The Scottish Ambulance Service continues to work closely with NHS Highland has been involved in meetings and the consultation regarding the redesign of Health and Social Care in the Skye, Lochalsh and South West Ross area. The Service attended a number of meetings across the area along with NHS Highland to help build public understanding about how our services fit within the integrated health and social care system and to answer any specific questions from community members about our role in the proposed changes to Health Care Services in this area. In recent years, ambulance staff establishment has increased across Skye: from five to six in Portree, four to five in Dunvegan, and we are recruiting in Broadford to take the establishment from six to nine. We have slightly increased our levels of cover in Portree and Broadford. In addition, we developed two Community First Responder schemes in Waternish and Glendale. We have also put an ambulance on to Raasay, which can be utilised by nominated local people on the island. Moreover, we have developed a system to for Paramedics access to Raasay with help from the Portree Lifeboat. These Paramedics can then use the ambulance that has been put on to the island. This is mainly used Out of Hours as an option in place of the ferry. We do still also have our air ambulance resources as a further option for responding to patients, depending on their clinical need. The skills level of our staff has also been improved with more Paramedics on the ambulances than before. -

S. S. N. S. Norse and Gaelic Coastal Terminology in the Western Isles It

3 S. S. N. S. Norse and Gaelic Coastal Terminology in the Western Isles It is probably true to say that the most enduring aspect of Norse place-names in the Hebrides, if we expect settlement names, has been the toponymy of the sea coast. This is perhaps not surprising, when we consider the importance of the sea and the seashore in the economy of the islands throughout history. The interplay of agriculture and fishing has contributed in no small measure to the great variety of toponymic terms which are to be found in the islands. Moreover, the broken nature of the island coasts, and the variety of scenery which they afford, have ensured the survival of a great number of coastal terms, both in Gaelic and Norse. The purpose of this paper, then, is to examine these terms with a Norse content in the hope of assessing the importance of the two languages in the various islands concerned. The distribution of Norse names in the Hebrides has already attracted scholars like Oftedal and Nicolaisen, who have concen trated on establis'hed settlement names, such as the village names of Lewis (OftedaI1954) and the major Norse settlement elements (Nicolaisen, S.H.R. 1969). These studies, however, have limited themselves to settlement names, although both would recognise that the less important names also merit study in an intensive way. The field-work done by the Scottish Place Name Survey, and localised studies like those done by MacAulay (TGSI, 1972) have gone some way to rectifying this omission, but the amount of material available is enormous, and it may be some years yet before it is assembled in a form which can be of use to scholar ship. -

![Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1473/inverness-county-directory-for-1887-1920-541473.webp)

Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]

INVERNE COUNTY DIRECTORY 899 PRICE ONE SHII.I-ING. COAL. A" I i H .J.A 2 Lomhara ^ai-eei. UNlfERNESS ^^OCKB XSEND \V It 'lout ^'OAL produced .^mmmmmmmm ESTABLISHED 1852. THE LANCASHIRE INSUBANCE COY. (FIRE, IIFE, AND EMPLOYERS' LIABILITY). 0£itpi±a.l, THf-eo IVIiliion® Sterling: Chief Offices EXCHANGE STREET, MANCHESTER Branch Office in Inverness— LANCASHIRE INSURANCE BUILDINGS, QUEEN'S GATE. SCOTTISH BOARD- SiR Donald Matheson, K.C.B., Cliairinan, Hugh Brown, Esq. W. H. KiDBTON, Esq. David S. argfll, Esq. Sir J. King of ampsie, Bart., LL.D. Sir H arles Dalrymple, of Newhailes, Andrew Mackenzie, Esq. of Dahnore. Bart., M.P. Sir Kenneth J. Matheson of Loclialsh, Walter Duncan, Esq, Bart. Alexander Fraser, Esq., InA^eriiess. Alexander Ross, Esq., LL.D., Inverness. Sir George Macpherson-Gr-nt, Bart. Sir James A. Russell, LL.D., Edin- (London Board). burgh. James Keyden, Esq. Alexander Scott, Esq., J. P., Dundee- Gl(is(f<nv Office— Edinhuvfih Office— 133 West Georf/e Street, 12 Torh JiiMilings— WM. C. BANKIN, Re.s. Secy. G. SMEA TON GOOLD, JRes. Secy. FIRE DEPARTMENT Tlie progress made in the Fire Department of the Company has been very marked, and is the result of the promptitude Avith which Claims for loss or damage by Fiie have always been met. The utmost Security is afforded to Insurers by the amjjle apilal and large Reserve Fund, in addition to the annual Income from Premiums. Insurances are granted at M> derate Rates upon almost every description of Property. Seven Years' Policies are issued at a charge for Six Years only. -

2018-03-15-NAC-Jelgersma-Bsc

Abstract Montagne Noire, part of the southern Massif Central in France, is the border between two climate types and therefore, it has always been subject to major and minor changes in temperature, rainfall and vegetation. This study aims to reconstruct the local paleoclimate of southern France by using a multi-proxy approach based on mineralogical (X-ray diffraction), geochemical (stable isotopes: C, O, H) and microscopic (scanning electron, petrographic and colour) analyses in a speleothem from Mélagues, located on the northern side of Montagne Noire. Temperature, rainfall and vegetation changes over time in the Mélagues region have been studied using the stable isotopic composition recorded in the speleothem. Although no dating of this speleothem is available yet, this study also examined possible relations with other regions and climate oscillations. Microscopic analyses of thin sections together with XRD analyses allowed us to determine the morphology, texture and mineralogy of the speleothem, which is composed of a mixture of magnesium calcite (∼70%), dolomite (∼25%, possibly formed through diagenetic processes) and a very low content of quartz (∼5%). Partial dissolution (∼5%) of the speleothem led to small voids (<40 µm) that were subsequently (partially) refilled by bacteria and microorganisms. Four columnar fabrics (compact, open, elongated and spherulitic) are observable in the studied speleothem, along with micrite, microsparite and mosaic fabrics. All these fabrics reflect (post-)depositional and environmental changes. The average temperature (∼14.8 °C) and vegetation (C3 plants) during deposition resemble the present-day temperature (14.8 ± 0.9 °C) and vegetation around our study site. Relatively high average 18O values (-4.38‰, 1σ ≈ 0.37) and relatively low average 13C values (-9.36‰, 1σ ≈ 0.55) of the stalagmite led us to interpret that the stalagmite was mainly deposited in a relatively warm and dry period, while seasonal precipitation from the Mediterranean Sea dominates the record. -

Exploring the Concept of Home at Hunter-Gatherer Sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe and Epipaleolithic Southwest Asia

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Homes for hunters?: Exploring the concept of home at hunter-gatherer sites in upper paleolithic Europe and epipaleolithic Southwest Asia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nt6f73n Journal Current Anthropology, 60(1) ISSN 0011-3204 Authors Maher, LA Conkey, M Publication Date 2019-02-01 DOI 10.1086/701523 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Current Anthropology Volume 60, Number 1, February 2019 91 Homes for Hunters? Exploring the Concept of Home at Hunter-Gatherer Sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe and Epipaleolithic Southwest Asia by Lisa A. Maher and Margaret Conkey In both Southwest Asia and Europe, only a handful of known Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic sites attest to aggregation or gatherings of hunter-gatherer groups, sometimes including evidence of hut structures and highly structured use of space. Interpretation of these structures ranges greatly, from mere ephemeral shelters to places “built” into a landscape with meanings beyond refuge from the elements. One might argue that this ambiguity stems from a largely functional interpretation of shelters that is embodied in the very terminology we use to describe them in comparison to the homes of later farming communities: mobile hunter-gatherers build and occupy huts that can form campsites, whereas sedentary farmers occupy houses or homes that form communities. Here we examine some of the evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic structures in Europe and Southwest Asia, offering insights into their complex “functions” and examining perceptions of space among hunter-gatherer communities. We do this through examination of two contemporary, yet geographically and culturally distinct, examples: Upper Paleolithic (especially Magdalenian) evidence in Western Europe and the Epipaleolithic record (especially Early and Middle phases) in Southwest Asia. -

TT Skye Summer from 25Th May 2015.Indd

n Portree Fiscavaig Broadford Elgol Armadale Kyleakin Kyle Of Lochalsh Dunvegan Uig Flodigarry Staffi Includes School buses in Skye Skye 51 52 54 55 56 57A 57C 58 59 152 155 158 164 60X times bus Information correct at time of print of time at correct Information From 25 May 2015 May 25 From Armadale Broadford Kyle of Lochalsh 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 Service No. 51 51 51A 51 51 NSch NSch NSch School Armadale Pier - - - - - 1430 - - Armadale Pier - - 1430 - - Holidays Only Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - - - - 1438 - - Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - 1433 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - - - - 1446 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - 1441 - - Drumfearn Road End - - - - - 1451 - - Drumfearn Road End - - 1446 - - Broadford Hospital Road End 0815 0940 1045 1210 1343 1625 1750 Broadford Hospital Road End 0940 1343 1625 1750 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0830 0955 1100 1225 1358 1509 1640 1805 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0955 1358 1504 1640 1805 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0835 1000 1105 1230 1403 1514 1645 1810 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 1000 1403 1509 1645 1810 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle of Lochalsh Broadford Armadale 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 51 Service No. 51 51A 51 51 51 NSch NSch NSch NSch School Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0740 0850 1015 1138 1338 1405 1600 1720 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0910 1341 1405 1600 1720 Holidays Only Kyleakin Youth -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

Store Cattle, Young Bulls and Young and Weaned Calves

THAINSTONE, Aberdeen and Northern Marts (Friday 2nd October 2020) Sold 1,129 Store Cattle, Young Bulls and Young and Weaned Calves. Bullocks (474) averaged 220.5p and £1,093.94 and sold to 287.7p per kg and £1,425 gross. West Highland Weaned Bullocks (57) averaged 257.4p (+57.3p on the year) and sold to 331.6p per kg and £1,080 gross. Heifers (506) averaged 223.4p and £1,010.91 and sold to 279.6p per kg and £1,305 gross. West Highland Weaned Heifers (59) averaged 240.1p (+56.1p on the year) and sold to 342.9p per kg and £945 gross. Bulls (8) sold to 322.2p per kg and £1,190 gross. Young and Weaned Calves (25) sold to £680 gross. THAINSTONE, Aberdeen and Northern Marts (Friday 2nd October 2020) Sold 1,129 Store Cattle, Young Bulls and Young and Weaned Calves. Bullocks (474) averaged 220.5p and £1,093.94 and sold to 287.7p per kg for a 212kg Simmental from Strone Croft, Newtonmore and £1,425 gross for a pen of 698kg Charolais from Newton of Auchindoir, Ryhnie. West Highland Weaned Bullocks (57) averaged 257.4p and sold to 331.6p per kg for a pair of 196kg Limousin from 1 Feorlig, Dunvegan and £1,080 gross for a 480kg Simmental from Heribost, Dunvegan. Heifers (506) averaged 223.4p and £1,010.91 and sold to 279.6p per kg for a 422kg Simmental from Tamala, Burnside and £1,305 gross for a 618kg Charolais from Lochend, Westray. West Highland Weaned Heifers (59) averaged 240.1p and sold to 342.9p per kg for a 140kg Limousin from 1 Feorlig and £945 gross for a 450kg Aberdeen Angus from Greep, Dunvegan. -

The Life of Flora Macdonald and Her Adventures with Prince Charles

. // National Library of Scotland *B000 143646* LIFE OF FLORA MACDONALD. A. KING AND COMPANY, 1R1NTERS TO THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN. ; THE LIFE OF FLORA MACDONALD, AND HER ADVENTURES WITH PRINCE CHARLES BY THE Rev. ALEXANDER MACGREGOR, M.A.j WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR, AND AN APPENDIX GIVING THE DESCENDENTS OF THE FAMOUS HEROINE BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A., Scot., EDITOR OF THE "CELTIC MAGAZINE"; AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES"; "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORUS OF THE ISLES"; ETC., ETC. INVERNESS : A. & W. MACKENZIE. 188 a. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/lifeoffloramacdo1882macg CONTENTS. PAGE Preface vii Memoir of the Author ix Chapter I. From Sheriffmuir to Culloden I Chapter II. From Culloden to the Long Island II Chapter III. Flora's Family, Youth, and Education 26 Chapter IV. Flora and the Prince in the Long Island 48 Chapter V. Flora and the Prince in the Isle of Skye—From Kingsburgh to Portree 86 Chapter VI. Flora a state prisoner—From Skye to London and back 106 Chapter VII. Flora's return to Skye—her warm reception—her marriage 120 Chapter VIII. Flora and her Husband emigrate to North Carolina 129 Chapter IX. Her Husband returns—They settle at Kingsburgh—Their deaths and funerals 138 Appendix 147 EDITOR'S PREFACE. >3=<- HE Life of Flora Macdonald, and her adventures with Prince Charles, ap- peared at different times in the Celtic Magazine, and it is now given to the public in this form to fill up a gap in the History of the Highlands ; for hitherto no complete authentic account of Flora Macdonald's Life has appeared.