DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 238 EA 027 303 TITLE Keepin' On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not Without a Fight-Final Draft 14 June 2018

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass EKU Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship Collection 2018 Not Without a Fight-Final Draft 14 June 2018 Richard E. Day Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/fs_research Part of the Education Commons Eastern Kentucky University From the SelectedWorks of Richard E. Day 2021 Not Without a Fight_Final Draft_14 uneJ 2018.doc Richard E. Day Available at: https://works.bepress.com/richard_day/69/ Not Without a Fight By Richard E. Day, Ed. D. When the pragmatically liberal Governor Bert T. Combs passed his 3% retail sales tax, in 1960, the people on the Cumberland Plateau felt a surge of confidence. After decades of neglect, local school boards in eastern Kentucky were finally able to offer qualified teachers with a college degree a raise of $900 dollars per year, and perhaps, stem the tide of good teachers who were leaving the region for bigger cities, or leaving the state for greener pastures in Ohio or Tennessee. The tax helped military veterans and funded new classrooms. Teacher standards were raised, a network of vocational schools and ten community colleges opened, and work began on the ambitious Kentucky Educational Television network which would greatly expand educational programming in rural areas. As lawyer and former Kentucky state legislator Harry M. Caudill reported, in his definitive Night Comes to the Cumberlands, that the public schools in eastern Kentucky lagged far behind. A 1960 University of Kentucky study found that high school graduates in Harlan County were performing three years and five months behind high school graduates nationally and were in no position to compete for good jobs. -

Power, Politics, and the 1997 Restructuring of Higher Education Governance in Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 POWER, POLITICS, AND THE 1997 RESTRUCTURING OF HIGHER EDUCATION GOVERNANCE IN KENTUCKY Michael Allen Garn University of Kentucky Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Garn, Michael Allen, "POWER, POLITICS, AND THE 1997 RESTRUCTURING OF HIGHER EDUCATION GOVERNANCE IN KENTUCKY" (2005). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 353. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/353 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Michael Allen Garn The College of Education University of Kentucky 2005 POWER, POLITICS, AND THE 1997 RESTRUCTURING OF HIGHER EDUCATION GOVERNANCE IN KENTUCKY ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Education at the University of Kentucky By Michael Allen Garn Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Susan J. Scollay, Associate Professor of Education Lexington, Kentucky Copyright © Michael Allen Garn 2005 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION POWER, POLITICS, AND THE 1997 RESTRUCTURING OF HIGHER EDUCATION GOVERNANCE IN KENTUCKY This study describes the policymaking process and policy solutions enacted in the Kentucky Postsecondary Improvement Act of 1997 (or House Bill 1). The study employs both an historical recounting of the “story” of House Bill 1 and a narrative analysis of opinion-editorials and policymaker interviews to reveal and explain how political power comprised both the perennial problem of Kentucky’s higher education policymaking – and the tool with which conflicts over power distribution were resolved. -

Presents Public Policy Luncheon Featuring Congressman Brett Guthrie Friday, May 11 at Noon See Page 9

20 YEARS OF PROVIDING MEMBER BUSINESSES WITH THE TOOLS TO SUCCEED USINESS OCUS20 BOFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF COMMERCE LEXINGTON INC. F MAY 2012 VOLUME XX, ISSUE V Presents Public Policy Luncheon Featuring Congressman Brett Guthrie Friday, May 11 at Noon See Page 9 GOOD MORNING BLUEGRASS: June 29th Event Features 3 Community Leaders New to the Area Who Will Share Their Impressions of Lexington & the Opportunities for Their Organizations and the Region. - SEE PAGE 13 www.CommerceLexington.com BUSINESS FOCUS May 2012: Volume XX, Issue V INSIDE THIS ISSUE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: 4-6 CirrusMio to Create Jobs, Locate in Downtown Lexington Business Focus is published once a month for a BBDP Economic Development Efforts Recognized total of 12 issues per year by Commerce Lexington Inc., 330 East Main Street, Suite 100, Lexington, Best in the BG Program Seeking Internship Opportunities KY 40507. Phone: (859) 226-1600 2012 Chair of the Board: Jeri Isbell, Vice President, Human Resources PUBLIC POLICY: Lexmark International, Inc. 7 Special Legislative Session Concludes with Passage of Prescription Drug Abuse Bill & Transportation Budget Publisher: Robert L. Quick, CCE, President & CEO Commerce Lexington Inc. 8-15 EVENTS: Editor: Mark E. Turner Resource Roundtable: Social Media & the Talent Landscape Communications Specialist: Elizabeth Bennett Policy Luncheon Features Congressman Brett Guthrie Printing: Post Printing Mail Service: Lexington Herald-Leader Business Owners Advisory Group Enrollment Event Crowne Plaza Hosts Business Link on June 12 Subscriptions are available for $12 and are included as a direct benefit of Commerce Lexington Inc. membership. Business Focus (USPS 012-337) periodical postage paid at GET CONNECTED: Lexington, Kentucky. -

Interactive Workshop Shows You How SEE PAGE 6 How to Recruit

20 YEARS OF PROVIDING MEMBER BUSINESSES WITH THE TOOLS TO SUCCEED USINESS OCUS20 BOFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF COMMERCE LEXINGTON INC. F JUNE 2012 VOLUME XX, ISSUE VI How To Recruit Awesome Interns Interactive Workshop Shows You How SEE PAGE 6 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Never Miss a Business Link Event Again With This Handy-Dandy Tear-Out Poster Sponsored by Blue & Co. That You Can Post in Your Business or Organization www.CommerceLexington.com BUSINESS FOCUS June 2012: Volume XX, Issue VI INSIDE THIS ISSUE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: 4-7 A&W Restaurants Celebrates Return to Lexington Business Focus is published once a month for a FrogDice to Celebrate New Location on June 15th total of 12 issues per year by Commerce Lexington Inc., 330 East Main Street, Suite 100, Lexington, Economic Development Team is On The Road Again KY 40507. Phone: (859) 226-1600 Workshop: How To Recruit Awesome Interns is June 19th Final Article in Series about Access Loan Program 2012 Chair of the Board: Jeri Isbell, Vice President, Human Resources Lexmark International, Inc. EVENTS: Publisher: 8-10 Crowne Plaza Hosts Business Link on Tuesday, June 12 Robert L. Quick, CCE, President & CEO Commerce Lexington Inc. Register Now for Commerce Lexington Inc. Golf Classic Good Morning Bluegrass Takes Newcomer Focus Editor: Mark E. Turner Communications Specialist: Elizabeth Bennett Printing: Post Printing Mail Service: Lexington Herald-Leader GET CONNECTED: Subscriptions are available for $12 and are 11-15 Once Upon a Story Distributes 7,000 Books to Kids included as a direct benefit of Commerce Lexington Inc. membership. Business Focus Leadership Central Kentucky: Clark County Recap (USPS 012-337) periodical postage paid at Leadership Central Ky. -

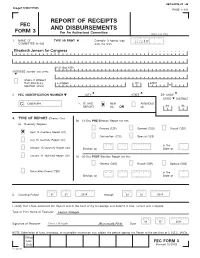

Report of Receipts and Disbursements

04/15/2014 23 : 46 Image# 14960797585 PAGE 1 / 161 REPORT OF RECEIPTS FEC AND DISBURSEMENTS FORM 3 For An Authorized Committee Office Use Only 1. NAME OF TYPE OR PRINT Example: If typing, type 12FE4M5 COMMITTEE (in full) over the lines. Elisabeth Jensen for Congress P.O. Box 1053 ADDRESS (number and street) Check if different than previously Lexington KY 40588 reported. (ACC) 2. FEC IDENTIFICATION NUMBER CITY STATE ZIP CODE STATE DISTRICT C C00545988 3. IS THIS NEW AMENDED REPORT (N) OR (A) KY 06 4. TYPE OF REPORT (Choose One) (b) 12-Day PRE -Election Report for the: (a) Quarterly Reports: Primary (12P) General (12G) Runoff (12R) April 15 Quarterly Report (Q1) Convention (12C) Special (12S) July 15 Quarterly Report (Q2) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the October 15 Quarterly Report (Q3) Election on State of January 31 Year-End Report (YE) (c) 30-Day POST -Election Report for the: General (30G) Runoff (30R) Special (30S) Termination Report (TER) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the Election on State of M M / D D / Y Y Y Y M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 5. Covering Period 01 2014 through 03 31 2014 I certify that I have examined this Report and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct and complete. Type or Print Name of Treasurer Laura A. D'Angelo M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 04 15 2014 Signature of Treasurer Laura A. D'Angelo [Electronically Filed] Date NOTE: Submission of false, erroneous, or incomplete information may subject the person signing this Report to the penalties of 2 U.S.C. -

Hometown Newspaper

A2 — SENTINEL-NEWS, SHELBYVILLE, KY., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 11, 2012 NEWS BRIEFS You may have awakened needs to be performed on their car. to a freeze in Shelby Human Rights Commission A freeze warning for Tuesday night signaled to honor pair an abrupt end to Kentucky’s unusually warm Rosa E. Alvarado and Joseph Humphrey early-spring weather. will be inducted into the Shelby County Human The National Weather Service predicted a Rights Commission’s Hall of Fame for 2012. low of 32 in Central Kentucky – maybe a degree They will be honored at the commission’s warmer in Shelby County – for overnight Tuesday, second annual hall-of-fame reception at 6:30 with temperatures in some areas possibly falling p.m. April 23 at Stratton Center in Shelbyville. into the upper 20s possible. The cold could To attend, RSVP by April 16 to ShelbyHRC@ damage or kill plants that were left uncovered. aol.com. For more information, contact Kevin Highs will be in the 50s and lows in the 30s Crittendon at 502-257-2406 or Gary L. Walls at through Thursday, well below the 80s recorded 502-655-0424. last month when record highs were set on March 19 and 21. 2012 Collins Leadership honorees “The persistence of warm weather was The 2012 Martha Layne Collins leadership what was notable,” said Rick Lasher, a weather awards will be presented two three women who service forecaster. “Usually, if we have a record will attend an awards luncheon on May 9 in in March, it’s warm for a few days and then Lexington. -

2002 SENATE RACES 34 Senate Races 20 Republican

2002 SENATE RACES 34 Senate Races 20 Republican-held Seats --14 Democrat-held Seats 6 Open Seats (NH, NJ NC, SC, TN, TX) – 5 currently Republican-held, 1 Democrat-held Current Senate Breakdown: 50 (D), 49 (R), 1 Independent (Votes With Democrats) PARTY STATE NOW DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN SEN. JEFF ALABAMA R Susan Parker SESSIONS ALASKA R Frank Vondersaar SEN. TED STEVENS ARKANSAS SEN. TIM R AG Mark Pryor HUTCHINSON COLORADO SEN. WAYNE R Tom Strickland ALLARD DELAWARE D SEN. JOSEPH BIDEN Ray Clatworthy GEORGIA D SEN. MAX CLELAND Rep.Saxby Chambliss IDAHO R Alan Blinken SEN. LARRY CRAIG ILLINOIS SEN. RICHARD D DURBIN Jim Durkin IOWA* D SEN. TOM HARKIN U.S. Rep. Greg Ganske KANSAS R No Democratic Candidate SEN. PAT ROBERTS KENTUCKY SEN. MITCH R Lois Combs Weinberg MCCONNELL LOUISIANA** SEN. MARY D LANDRIEU Three GOP Candidates MAINE SEN. SUSAN R Chellie Pingree COLLINS MASSACHUSETTS No Republican D SEN. JOHN KERRY Candidate MICHIGAN D SEN. CARL LEVIN Andrew Raczkowski MINNESOTA*** SEN. PAUL D WELLSTONE Norm Coleman MISSISSIPPI SEN. THAD R No Democratic Candidate COCHRAN MISSOURI SEN. JEAN D CARNAHAN Jim Talent MONTANA No Republican D SEN. MAX BAUCUS Candidate NEBRASKA SEN. CHUCK R Charles Matulka HAGEL NEW HAMPSHIRE R Gov. Jeanne Shaheen U.S. Rep. John Sununu NEW JERSEY Fmr. Sen. Frank D Lautenberg Douglas Forrester NEW MEXICO SEN. PETE R Gloria Tristani DOMENICI NORTH CAROLINA R Erskine Bowles Elizabeth Dole OKLAHOMA SEN. JAMES R David Walters INHOFE OREGON**** SEN. GORDON R Bill Bradbury SMITH RHODE ISLAND D SEN. JACK REED Bob Tingle SOUTH CAROLINA R Alex Sanders Rep. -

Perspectives 10X10.Indd

N. Ky. Advocate THANKS TO OUR PLATINUM LEVEL SPONSOR Joins Prichard Staff Brigitte Blom Ramsey of Falmouth joined the Prichard Committee staff in May as associate executive director. She previ- ously served as director of strategic resour- ces and public policy at the United Way Perspectives of Greater Cincin- nati and co-chaired VOLUME 25 | FALL 2014 the Northern Ken- tucky Education Action Team. Students’ Input Elevating Policy Issues Ramsey is a Voice Team Growing, Studying Postsecondary Transitions member of Ken- The Prichard Committee’s Student Voice Team Beshear for backing of education funding increases. tucky’s Early Child- ended its pilot year strong: preparing to call attention With no formal recruitment effort, the group hood Advisory to ways state policymakers and education leaders can expanded beyond its initial central Kentucky mem- Council and was Ramsey improve transitions after high school. bership and now includes 30 middle and high school appointed in 2008 by Gov. Steve Beshear to Among a spate of activities last year, the group students with members from Elizabethtown and Jef- the State Board of Education. She resigned mobilized other students in a statewide social media ferson, Green and Knox counties. that position upon joining the Prichard staff. campaign to push for increased education funding in One of the most ambitious undertakings, howev- “Members of the Prichard Committee the state’s 2015-16 budget and made the featured pre- er, is still in the works, as members develop a strategy believe that engaging, educating and em- sentation at an event in Frankfort to hail Gov. Steve See VOICE, Page 8 powering citizens makes a difference, and See RAMSEY, Page 5 31 Years of Action, Answers, Progress Lexington, Lexington, KY Lexington, Lexington, 40507 KY Permit No. -

AGENDA September 21, 1997

AGENDA Council on Postsecondary Education September 21, 1997 1:00 p.m. (ETI, Summit B & C Meetin Room located on second flood, Louisville Marriott East, Louisville, KY A. Roll Call B. Approval of Minutes ..................................................................................................1 C. The Status of Kentucky Postsecondary Education: In Transition .............................9 D. CPE Transition Agenda ............................................................................................ l l E. Kentucky Plan for Equal Opportunities — Charles Whitehead, Chair, Committee on Equal Opportunities..............................45 F. Technical School Presentation — Delmus Murrell, Acting Commissioner, Department for Technical Education......53 G. Kentucky Community and Technical College System: An Update — James R. Ramsey (Acting President) and Martha Johnson (Chair), Kentucky Community and Technical College System ............................................55 H. 1998-2000 Biennial Operating and Capital Budget Development and Incentive Funds —Aims McGuinness, NCHEMS ............................................57 I. CPE Mission Statement Development .....................................................................59 J. Other Business K. Next Meeting L. Adjournment Action items are indicated by italics. Sundax. Septel116e1' 21 (held in conjunction with the Governor's Conference on Postsecondary Education Trusteeship at the Louisville Marriott East) 12 noon —1 p.m. (ET) informal lunch in the Ambassador Room (located -

The Slow and Unsure Progress of Women in Kentucky Politics Author(S): Penny M

Kentucky Historical Society The Slow and Unsure Progress of Women in Kentucky Politics Author(s): Penny M. Miller Source: The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 99, No. 3, Special Issue on Kentucky Women in Government and Politics (Summer 2001), pp. 249-284 Published by: Kentucky Historical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23384605 Accessed: 24-02-2020 21:59 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23384605?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Kentucky Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society This content downloaded from 161.6.45.57 on Mon, 24 Feb 2020 21:59:42 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Slow and Unsure Progress of Women in Kentucky Politics by Penny M. Miller The voice of women in Kentucky politics has been largely muted during the commonwealth's two-plus centuries of state hood. As voters, appointed officeholders, members of boards and commissions, party activists, interest-group participants, lobbyists, campaign contributors, and as elected local and state wide officials and judges, women in Kentucky have lagged behind women in the nation, who themselves have been largely marginalized.