Spencer Habluetzel, Is Your Shotgun Sporting?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial-Statement-Reasons-11-17.Pdf

INITIAL STATEMENT OF REASONS PROBLEM STATEMENT Penal Code (PC) section 30515 specifies characteristics that identify a firearm as an assault weapon. Section 5471 of title 11, division 5, California Code of Regulations (CCR) further defines terms used in PC section 30515 to describe those characteristics, for the purpose of the requirement to register with the Department of Justice (DOJ) a new class of assault weapons by stating assault weapons that do not have a fixed magazine, as defined in PC section 30515, including those weapons with an ammunition feeding device that can be readily removed from the firearm with the use of a tool, as provided in PC section 30900(b)(1). Section 5471 defines forty-four terms used in the identification of assault weapons pursuant to PC section 30515 or otherwise used in the section 5471 definitions themselves. Aside from the registration definitions set forth in section 5471, there currently are no definitions of the terms used in PC section 30515 to identify a firearm as an assault weapon. BENEFITS The proposed regulation will apply the definitions of terms in CCR section 5471 to the identification of assault weapons pursuant to PC section 30515, without limitation to context of the new registration process. This regulation will provide detailed, concrete information regarding firearms that constitute assault weapons. The proposed regulation will promote efficiency within the DOJ, as well as provide uniform guidance to the public, the judiciary, district attorney’s offices, and law enforcement agencies throughout California. PURPOSE AND NECESSITY PC section 30515 contains specific characteristic definitions of assault weapons. -

California State Laws

State Laws and Published Ordinances - California Current through all 372 Chapters of the 2020 Regular Session. Attorney General's Office Los Angeles Field Division California Department of Justice 550 North Brand Blvd, Suite 800 Attention: Public Inquiry Unit Glendale, CA 91203 Post Office Box 944255 Voice: (818) 265-2500 Sacramento, CA 94244-2550 https://www.atf.gov/los-angeles- Voice: (916) 210-6276 field-division https://oag.ca.gov/ San Francisco Field Division 5601 Arnold Road, Suite 400 Dublin, CA 94568 Voice: (925) 557-2800 https://www.atf.gov/san-francisco- field-division Table of Contents California Penal Code Part 1 – Of Crimes and Punishments Title 15 – Miscellaneous Crimes Chapter 1 – Schools Section 626.9. Possession of firearm in school zone or on grounds of public or private university or college; Exceptions. Section 626.91. Possession of ammunition on school grounds. Section 626.92. Application of Section 626.9. Part 6 – Control of Deadly Weapons Title 1 – Preliminary Provisions Division 2 – Definitions Section 16100. ".50 BMG cartridge". Section 16110. ".50 BMG rifle". Section 16150. "Ammunition". [Effective until July 1, 2020; Repealed effective July 1, 2020] Section 16150. “Ammunition”. [Operative July 1, 2020] Section 16151. “Ammunition vendor”. Section 16170. "Antique firearm". Section 16180. "Antique rifle". Section 16190. "Application to purchase". Section 16200. "Assault weapon". Section 16300. "Bona fide evidence of identity"; "Bona fide evidence of majority and identity'. Section 16330. "Cane gun". Section 16350. "Capacity to accept more than 10 rounds". Section 16400. “Clear evidence of the person’s identity and age” Section 16410. “Consultant-evaluator” Section 16430. "Deadly weapon". Section 16440. -

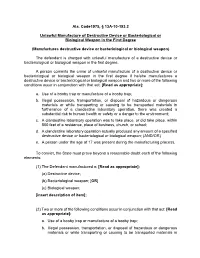

Ala. Code1975, § 13A-10-193.2 Unlawful Manufacture of Destructive Device Or Bacteriological Or Biological Weapon in the First

Ala. Code1975, § 13A-10-193.2 Unlawful Manufacture of Destructive Device or Bacteriological or Biological Weapon in the First Degree (Manufactures destructive device or bacteriological or biological weapon) The defendant is charged with unlawful manufacture of a destructive device or bacteriological or biological weapon in the first degree. A person commits the crime of unlawful manufacture of a destructive device or bacteriological or biological weapon in the first degree if he/she manufactures a destructive device or bacteriological or biological weapon and two or more of the following conditions occur in conjunction with that act: [Read as appropriate]: a. Use of a booby trap or manufacture of a booby trap; b. Illegal possession, transportation, or disposal of hazardous or dangerous materials or while transporting or causing to be transported materials in furtherance of a clandestine laboratory operation, there was created a substantial risk to human health or safety or a danger to the environment; c. A clandestine laboratory operation was to take place, or did take place, within 500 feet of a residence, place of business, church, or school; d. A clandestine laboratory operation actually produced any amount of a specified destructive device or bacteriological or biological weapon; (AND/OR) e. A person under the age of 17 was present during the manufacturing process. To convict, the State must prove beyond a reasonable doubt each of the following elements: (1) The Defendant manufactured a: [Read as appropriate]: (a) Destructive device; (b) Bacteriological weapon; [OR] (c) Biological weapon; [insert description of item]; (2) Two or more of the following conditions occur in conjunction with that act: [Read as appropriate]: a. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 11-50536 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 3:10-cr-04083- WQH-1 YOAHJAN LARA FLORES, Defendant-Appellant. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 11-50539 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 3:10-cr-04083- WQH-3 ALFREDO RUBIO LARA, Defendant-Appellant. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 11-50555 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 3:10-cr-04083- WQH-2 ARTURO LARA, Defendant-Appellant. OPINION 2 UNITED STATES V. FLORES Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of California William Q. Hayes, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted March 7, 2013—Pasadena, California Filed August 30, 2013 Before: Richard A. Paez and Paul J. Watford, Circuit Judges, and Leslie E. Kobayashi, District Judge.* Opinion by Judge Paez SUMMARY** Criminal Law Vacating sentences and remanding for resentencing for conspiracy to possess an unregistered firearm, the panel held that the definition of a missile under 26 U.S.C. § 5845(f) and U.S.S.G. § 2K2.1(b)(3)(A) is a self-propelled device designed to deliver an explosive. The panel concluded that because the 40-mm cartridges in this case do not qualify as missiles, the district court erred * The Honorable Leslie E. Kobayashi, District Judge for the U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii, sitting by designation. ** This summary constitutes no part of the opinion of the court. It has been prepared by court staff for the convenience of the reader. UNITED STATES V. -

The Relevance of a Defendant's Subjective Intent in Defining a “Destructive Device” Under the National Firearms Act

Fordham Law Review Volume 79 Issue 2 Article 6 November 2011 Just a Soul Whose Intentions Are Good? The Relevance of a Defendant's Subjective Intent in Defining a “Destructive Device” Under the National Firearms Act Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Just a Soul Whose Intentions Are Good? The Relevance of a Defendant's Subjective Intent in Defining a “Destructive Device” Under the National Firearms Act, 79 Fordham L. Rev. 563 (2011). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol79/iss2/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUST A SOUL WHOSE INTENTIONS ARE GOOD? THE RELEVANCE OF A DEFENDANT’S SUBJECTIVE INTENT IN DEFINING A “DESTRUCTIVE DEVICE” UNDER THE NATIONAL FIREARMS ACT Elliot Buckman* This Note addresses the three-way circuit split among the U.S. Courts of Appeals over when, and to what extent, a court may consider a defendant’s subjective intent in defining a “destructive device” under the National Firearms Act. The circuit split centers on the Act’s ambiguous reference to intent in its definition of a destructive device, which is a statutorily prohibited firearm. After discussing the Act’s legislative history and development, this Note considers the role of mens rea in National Firearms Act cases. -

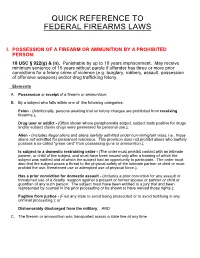

Quick Reference to Federal Firearms Laws

QUICK REFERENCE TO FEDERAL FIREARMS LAWS I. POSSESSION OF A FIREARM OR AMMUNITION BY A PROHIBITED PERSON: 18 USC § 922(g) & (n). Punishable by up to 10 years imprisonment. May receive minimum sentence of 15 years without parole if offender has three or more prior convictions for a felony crime of violence (e.g. burglary, robbery, assault, possession of offensive weapons) and/or drug trafficking felony. Elements A. Possession or receipt of a firearm or ammunition; B. By a subject who falls within one of the following categories: Felon - (Additionally, persons awaiting trial on felony charges are prohibited from receiving firearms.); Drug user or addict - (Often shown where paraphernalia seized, subject tests positive for drugs and/or subject claims drugs were possessed for personal use.); Alien - (Includes illegal aliens and aliens lawfully admitted under non-immigrant visas, i.e., those aliens not admitted for permanent residence. This provision does not prohibit aliens who lawfully possess a so-called “green card” from possessing guns or ammunition.); Is subject to a domestic restraining order - (The order must prohibit contact with an intimate partner, or child of the subject, and must have been issued only after a hearing of which the subject was notified and at which the subject had an opportunity to participate. The order must also find the subject poses a threat to the physical safety of the intimate partner or child or must prohibit the use, threatened use or attempted use of physical force.); Has a prior conviction for domestic assault - (Includes a prior conviction for any assault or threatened use of a deadly weapon against a present or former spouse or partner or child or guardian of any such person. -

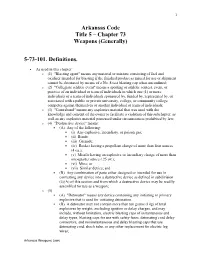

Arkansas Code Title 5 – Chapter 73 Weapons (Generally) 5-73-101. Definitions

1 Arkansas Code Title 5 – Chapter 73 Weapons (Generally) 5-73-101. Definitions. As used in this chapter: o (1) "Blasting agent" means any material or mixture consisting of fuel and oxidizer intended for blasting if the finished product as mixed for use or shipment cannot be detonated by means of a No. 8 test blasting cap when unconfined; o (2) "Collegiate athletic event" means a sporting or athletic contest, event, or practice of an individual or team of individuals in which one (1) or more individuals or a team of individuals sponsored by, funded by, represented by, or associated with a public or private university, college, or community college competes against themselves or another individual or team of individuals; o (3) "Contraband" means any explosive material that was used with the knowledge and consent of the owner to facilitate a violation of this subchapter, as well as any explosive material possessed under circumstances prohibited by law; o (4) "Destructive device" means: . (A) Any of the following: . (i) Any explosive, incendiary, or poison gas; . (ii) Bomb; . (iii) Grenade; . (iv) Rocket having a propellant charge of more than four ounces (4 oz.); . (v) Missile having an explosive or incendiary charge of more than one-quarter ounce (.25 oz.); . (vi) Mine; or . (vii) Similar device; and . (B) Any combination of parts either designed or intended for use in converting any device into a destructive device as defined in subdivision (4)(A) of this section and from which a destructive device may be readily assembled for use as a weapon; o (5) . (A) "Detonator" means any device containing any initiating or primary explosive that is used for initiating detonation. -

Notice of Lodging and Lodging of Federal Authorities

12 IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 13 IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF FRESNO 14 EDWARD W. HUNT, in his official ) CASE NO. 01CECG03182 capacity as District Attorney of Fresno ) 15 County, and in his personal capacity as a ) NOTICE OF LODGING AND LODGING OF citizen and taxpayer, et. aI., ) FEDERAL AUTHORITIES 16 ) Plaintiffs, ) Date: April 10, 2002 17 ) Time: 3:00 p.m. v. ) Dept.: 98A 18 STATE OF CALIFORNIA; WILLIAM ) 19 LOCKYER, Attorney General of the State of~ California, et. aI., ) 20 Defendants. ) 21 -------------------------) 22 Plaintiffs hereby lodges the following federal authorities cited in our Reply to Defendants' 23 Opposition for Preliminary Injunction: 24 l. Crandon v. United States (1990) 494 US 152 [110 S.Ct. 997, 108 L.Ed.2d 132]. 25 2. Davis v. Erdmann (10th Cir. 1979) 607 F.2d 917. 26 3. Evans v. u.s. Parole Com'n (7th Cir. 1996) 78 F.3d 262. 27 4. F.J Vollmer Co., Inc. v. Higgins (D.C.Cir. 1994) 23 F.3d 448 [306 U.S.App.D.C. 140]. 28 1 NOTICE OF LODGING OF AUTHORITIES AP~. 4. 2002 5: 16PM NO. 2576 P. 8 -- 1 C.D. Michel- S.B.N. 144258 TRUTANICH • MICHEL, LLP 2 Port of Los Angeles 407 North Harbor Boulevard 3 San Pedro, California 90731 (310) 548-0410 4 .~ ~'l ~[DJ Stephen P. Halbrook 5 LAW OFFICES OF STEPHEN p, HALBROOK APR • ~~ 20~~ 10560 Main Street.1 Suite 404 6 Fairfax, Virginia 22030 FR~SNO COUNTY SUPERIOR COU~T (703) 352-7276 Ev 7 • ----:Cr""'l:X-.=DE::;;"PU;;-;'l'( Don B. -

Summary of Federal Firearms Laws

SUMMARY OF FEDERAL FIREARMS LAWS OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY DISTRICT OF MAINE SEPTEMBER 2010 Summary Of Federal Firearms Laws—September 2010 INTRODUCTION Maine has historically had a violent crime rate well below the national average. Nonetheless, every effort must be made to further reduce violence to ensure that we are safe on our streets and in our homes. Because the causes of violence in Maine and in society generally are numerous and varied, the solutions require a concerted national and local effort. To that end, the Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Maine have instituted Project Safe Neighborhoods (PSN Maine), an initiative designed to reduce gun violence in Maine. A PSN Task Force including representatives from local and state law enforcement, domestic violence groups, schools, civic groups and business works to develop a comprehensive strategy to address this issue. Part of this strategy includes support for violent crime task forces in Lewiston and Bangor and an aggressive enforcement policy for gun crimes. The federal government has generally lacked jurisdiction to prosecute many violent crimes. Accordingly, the burden has traditionally fallen upon state and local law enforcement officers and prosecutors. However, Congress has increasingly broadened federal jurisdiction which enables federal agents and federal prosecutors to become more involved in the enforcement effort against violence. This document is designed to be a concise summary of some of the federal statutes which can be used to prosecute violent offenders. It is not all-inclusive; however, it describes the principal statutes available. By distributing this information, we hope to generate referrals of cases to our office or the appropriate federal agency and hence assist state prosecutors and law enforcement personnel in their efforts to combat violent crime within our state. -

“Firearms” Under the Nfa?

ATF E-Publication 5320.8 June 2007 PREFACE This handbook is primarily for the use of persons in the business of importing, manufacturing, and dealing in firearms defined by the National Firearms Act (NFA) or persons intending to go into an NFA firearms business. It should also be helpful to collectors of NFA firearms and other persons having questions about the application of the NFA. This publication is not a law book. Rather, it is intended as a “user friendly” reference book enabling the user to quickly find answers to questions concerning the NFA. Nevertheless, it should also be useful to attorneys seeking basic information about the NFA and how the law has been interpreted by ATF. The book’s Table of Contents will be helpful to the user in locating needed information. Although the principal focus of the handbook is the NFA, the book necessarily covers provisions of the Gun Control Act of 1968 and the Arms Export Control Act impacting NFA firearms businesses and collectors. The book is the product of a joint effort between ATF and the National Firearms Act Trade and Collectors Association. ATF takes this opportunity to express its appreciation to the Association for its assistance in writing and making this publication possible. i TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION Sec. 1.1 History of the National Firearms Act (NFA).......................................................................1 1.1.1 The NFA of 1934 1.1.2 Title II of the Gun Control Act of 1968 1.1.3 Firearm Owners’ Protection Act Sec. 1.2 Meaning of terms .................................................................................................................2 1.2.1 “AECA” 1.2.2 “ATF” 1.2.3 “ATF Ruling” 1.2.4 “CFR” 1.2.5 “DIO” 1.2.6 “FFL” 1.2.7 “FTB” 1.2.8 “GCA” 1.2.9 “NFA” 1.2.10 “NFRTR” 1.2.11 “SOT” 1.2.12 “U.S.C.” Sec. -

Vermont State Laws and Published Ordinances

State Laws and Published Ordinances – Vermont Statutes are current with all legislation through Act 130 of the 2019 Vermont General Assembly Office of the Attorney General Boston Field Division 109 State Street 10 Causeway Street, Suite 791 Montpelier, VT 05609-1001 Boston, MA 02222 Voice: (802) 828-3171 Voice: (617) 557-1200 https://ago.vermont.gov/ https://www.atf.gov/boston-field-division Table of Contents Title 13 – Crimes and Criminal Procedure Part 1 – Crimes Chapter 37 – Explosives Section 1603. Definitions. Section 1604. Possession of destructive devices. Chapter 85 – Weapons Subchapter 1 – Generally Section 4004. Possession of dangerous or deadly weapon in a school bus or school building or on school property. Section 4006. Record of firearm sales. Section 4007. Furnishing firearms to children. Section 4008. Possession of firearms by children. Section 4010. Gun suppressors. Section 4013. Zip guns; switchblade knives. Section 4014. Purchase of firearms in other states. Section 4015. Purchase of firearms by nonresidents. Section 4017. Persons prohibited from possessing firearms; conviction of violent crime. Section 4019. Firearms transfers; background checks. Section 4020. Sale of firearms to persons under 21 years of age prohibited. Section 4022. Bump-fire stocks; possession prohibited. Subchapter 2 – Extreme Risk Protection Orders Section 4051. Definitions. Section 4053. Petition for extreme risk protection order. Section 4054. Emergency relief; temporary ex parte order. Section 4055. Termination and renewal motions. Section 4059. Relinquishment, storage, and return of dangerous weapons. Section 4060. Appeals. Section 4061. Effect on other laws. Title 24 – Municipal and County Government Part 2 – Municipalities Chapter 61 – Regulatory Provisions; Police Power of Municipalities Subchapter 11 – Miscellaneous Regulatory Powers Section 2295. -

ATF) Summary of the PGA Process for Filing in ACE

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) Summary of the PGA Process for Filing in ACE February 24, 2016 Version 1.1 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) Contents 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….2 2. Commodities…………………………………………………………………………...………2 3. Forms/Documents…………………………………………………………………………...…5 4. Downtime Procedures………………………………………………………………….............5 5. Filing ATF PGA Data………………………………………………………………….........…6 6. Points of Contact………………….. ………………………………………………………......7 i 1. Introduction The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) is a law enforcement agency in the United States Department of Justice. ATF's responsibilities include the investigation and prevention of federal offenses involving the unlawful use, manufacture, and possession of firearms and explosives; acts of arson and bombings; and illegal trafficking of alcohol and tobacco products. ATF also regulates licensing, the sale, possession, and transportation of firearms, ammunition, and explosives in interstate commerce. 2. Commodities ATF regulates firearms, explosives, ammunition and implements of war. ATF does not utilize HTUS number flagging associated with its regulated commodities. ATF utilizes commodity type descriptions and commodity type codes in order to identify its regulated commodities, please see the table below. The table also indicates when a license, permit or certification (LPC) is required for each weapon category code. (In the table below FEL = Federal Explosives License, FFL=Federal Firearms