Towards Improving Food Security and Sustainable Livelihoods of Resource Poor Farmers in Bangladesh : Impact of the Foshol Projec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Batayan Vol7

"®LE h¡ ¢eM¡c HL¡L£ A¿¹l¡ ¢eT¥j ®gl hCfšl ¢Le n¡¢ju¡e¡l eLn¡ a¡L V¡e je ¢cuR ¢mVm jÉ¡N¡¢Se z ---- ----- ----- ----- ----- ®l¡c EWR n£al pL¡mhm¡ z S¡em¡ M¤m HLm¡ hp i¡¢h, ®g¡e a¥m ¢eC z hå¥L ®gl h¢m- "BS ¢hLm hCjm¡a k¡¢h ?'' _ nË£S¡a ""BS c¤f¤l'' pÇf¡ce¡ l¢”a¡ Q–¡f¡dÉ¡u pçj pwMÉ¡, j¡QÑ, 2017 Issue Number 7 : March, 2017 EDITORS Ranjita Chattopadhyay, Chicago, IL Jill Charles, IL, USA (English Section) COORDINATOR Biswajit Matilal, Kolkata, India DESIGN AND ART LAYOUT Kajal & Subrata, Kolkata, India PHOTOGRAPHY Soumen Chattopadhyay, IL, USA Tirthankar Banerjee, Perth, Australia PUBLISHED BY Neo Spectrum Anusri Banerjee, Perth, Australia E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Our heartfelt thanks to all our contributors and readers for overwhelming support and response. h¡a¡ue f¢œL¡ ¢eJØfLVÊ¡jÚ à¡l¡ fËL¡¢na J phÑpšÄ pwl¢ra z fËL¡nLl ¢m¢Ma Ae¤j¢a R¡s¡, HC f¢œL¡u fËL¡¢na ®k ®L¡e Awnl f¤ejѤâZ h¡ ®k ®L¡e i¡h hÉhq¡l ¢e¢oÜ z lQe¡u fËL¡¢na ja¡ja pÇf§ZÑ i¡h lQ¢ua¡u p£j¡hÜ z BATAYAN is published by Neo Spectrum. No part of the articles in this issue can be re-printed without the prior approval of the publisher. The editors are not responsible for the contents of the articles in this issue. -

Download File

NEED ASESSMENT OF PLAIN LAND ADIBASI or INDEGIENOUS PEOPLE Geographical Location: Dinajpur and Thakurgaon District Duration: 06-15 May 2017 Need Assessment by: SOLAR Program Team, CDA Ref: CDA’s SOLAR Program, Budget line: 3.1.05, Fiscal year 2016-2017. Supported by: Bread for the World, Germany. Chandipur village/People Organization(PO): IP women participated during the need assessment COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION (CDA) Upa- shahar, house#51, Road#9, Dinajpur 5200, Bangladesh, Mobile: 01713195000, 01712251333, Telephone: 053164428 , email: edcda08@gmail, [email protected], Website: www.cdalpo.org 1 Contents SL# Contents Page# Forwarding 2 1 Background of the report 4 2 Need assessment context 4 3 Need assessment Goal 4 4 Objectives 4 5 Activities of Assessment Team 4 6 Assessment/survey tool used 4 7 Methodology 5 8 Household level composition/variables 5 9 Assessment findings according to composition or variables 5-14 9.1 Social stratification 5-6 9.2 Access to land 6 9.3 Seasonal drawback 7 9.4 Seasonal employment 8 9.5 Household population 8-9 9.6 Age and Sex of household head 9 9.7 Social Dignity of Indigenous People (IP) 9-10 9.8 Poverty of indigenous People (IP) 11 9.9 Poverty line link with SDGs and LDC achieved indicator 12-13 9.10 Non-Monetary composition of indigenous people (IP) 13-14 9.11 Level of deprivation from Non-monetary composition 14 10 Need perceived by IP households 15-16 11 Recommendation 17 12 Conclusion 17 2 Forwarding ________________________________________________________________________________ Community Development Association (CDA) has been performing a facilitating role to the poorest, landless and marginal farmers along with the plain land indigenous people (IP) including the differently able men, women & youth with a view to empower, ensure and secure access to land Rights through implementation of People Centered Development Strategies since 1986 in the Northwestern part of Bangladesh. -

THE IMPACT of RICE PRICES on the NUTRITIONAL STATUS of CHILDREN in Rural Bangladesh August 1996

.p~-~y-q{~ 9~ 22....<.( THE IMPACT OF RICE PRICES ON THE NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF CHILDREN in Rural Bangladesh August 1996 Nutritional Surveillance Project (NSP) ~ BANGLADESH Acknowledgement number of persons outside of Helen Keller International have provided valuable inputs to the development of this document and we wish to express our thanks for their contributions. AMr. David Atwood, Deputy Director of the Office of Food and Agriculture of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mission to Bangladesh reviewed and commented on the analytic methodology at the outset. Dr. M. Mahmud Khan, Associate Professor, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and Dr. Binayak Sen, Research Fellow of the Bangladesh Institute ofDevelopment Studies (BIDS) have both reviewed this document in draft form and provided valuable comments and insight. Dr. Gillian Hall is currently completing her doctoral thesis at the Australian National University based on data collected from ten thanas of the Nutritional Surveillance Project (NSP). A number of the issues explored in this paper will also be addressed in Dr. Hall's work. She has provided a good deal of guidance in these analyses and has kindly reviewed this document in draft form and provided extensive comments. We gratefully acknowledge this input, any remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors. The NSP is financed by the USAID Mission to Bangladesh under grant No. 388-0081-G-OO-4042-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. THE IMPACT OF RICE PRICES ON THE NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF CHILDREN Executive Summary to segregate households with different socioeconomic characteristics and identify their response to different his report explores rice price fluctuations and price levels measured by household consumption, their impact on household food expenditure, expenditure and distress indicators. -

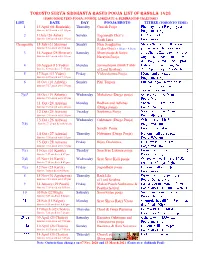

Toronto Surya Siddhanta Based Pooja List of Bangla 1428

TORONTO SURYA SIDDHANTA BASED POOJA LIST OF BANGLA 1428 (BARO MASE TERO POOJA; SOURCE: LOKENATH & BENIMADHOB CALENDAR) LIST DATE DAY POOJA/BROTO TITHEE (TORONTO TIME) 1 15 April (01 Boishakh) Thursday Ganesh Pooja Sun rise 6:34 am & set 8: 01 pm 2 11July (26 Ashar) Sunday Jogonnath Dev’s Sun rise 5:46 am & set 8: 59 pm Roth Jatra Changeable 18 July (01 Shravon) Sunday Nam Songkirton Sun rise 5:52 am & set 8:54 pm (Udoy-Osto) 4:50 am - 9:51pm 3 14 August (28 Shravon) Saturday Shoni pooja & Sotyo Sun rise 6:21 am & set 8: 22 pm Narayon Pooja 4 30 August (13 Vadro) Monday Jonmashtomi (Birth Tithhi Sun rise 6:39am & set 7: 55 pm of Lord Krishna) 5 17 Sept. (31 Vadro) Friday Vishwokorma Pooja Sun rise 6:59 am & set 7: 23 pm 6 03 Oct. (16 Ashwin) Sunday Pitri Torpon Sun rise 7:17 am & set 6: 54 pm 7(a)* 06 Oct. (19 Ashwin) Wednesday Mohaloya (Durga pooja) Sun rise 7:21 am & set 6: 49 pm 11 Oct (24 Ashwin) Monday Bodhon and Adhibas Sun rise 7:27 am & set 6: 40 pm (Durga pooja) 12 Oct (25 Ashwin) Tuesday Soptomee Pooja Sun rise 7:28 am & set 6: 38 pm 13 Oct (26 Ashwin) Wednesday Oshtomee (Durga Pooja) 7(b) Sun rise 7: 29 am & set 6:36 pm Sondhi Pooja 14 Oct (27 Ashwin) Thursday Nobomee (Durga Pooja) Sun rise 7:30 am & set 6: 35 pm 15 Oct (28 Ashwin) Friday Bijoy Doshomee Sun rise 7:32 am & set 6: 33 pm 7(c) 19 Oct. -

2021 Drik Panchang Bengali Festivals Calendar

Created via PDFShift 2021 Drik Panchang Bengali Festivals Calendar Bengali Festivals Calendar for New Delhi, NCT, India Location: New Delhi, India Date of Creation: October 1, 2020, Thursday Latitude: 28° 38′ 08″ N Version: v1.0.0 Longitude: 77° 13′ 28″ E Elevation: 212 m Olson Timezone: Asia/Kolkata Timezone: 5.5 Registered Office: Branch Office: 010, United Daffodils, BMA College Road 187-D, Radha Nagar Doddanekundi, Marathahalli Outer Ring Road Krishna Nagar Post Office Bengaluru - 560037 Mathura - 281004 This is a month wise list of most Bengali festivals in the year 2021. Most of the Bengali festivals are determined based on the position of the Sun and the Moon. Bengali Festivals depend on geographic location and might differ for Page 1 of 6 two cities and difference is quite noticeable for cities in different time zone. Hence one should set the location before looking into the festival list. Created via PDFShift January 2021 Makara Sankranti 14 January 14, 2021, Thursday Thursday Dhanu to Makara transit of Sun Magh Bihu 15 January 15, 2021, Friday Friday based on Solar calendar February 2021 Kumbha Sankranti 12 February 12, 2021, Friday Friday Makara to Kumbha transit of Sun Saraswati Puja 16 February 16, 2021, Tuesday Tuesday Magh, Shukla Panchami March 2021 Maha Shivaratri 11 March 11, 2021, Thursday Thursday Magh, Krishna Chaturdashi Meena Sankranti 14 March 14, 2021, Sunday Sunday Kumbha to Meena transit of Sun Dol Purnima 28 March 28, 2021, Sunday Sunday Falgun, Shukla Purnima April 2021 Solar New Year Mesha Sankranti 14 April -

What Matters?

Rohingya Burmese, Gregorian, Islamic Hijri, Bangla: emergency in Which calendar Rohingya people use in WHAT local newspapers everyday life. Find out more on page 5 Find out more on page 2 MATTERS? Humanitarian Feedback Bulletin Issue 03 × Wednesday, April 18, 2018 BBC Media Action, Internews, and Translators Without Borders are working together to collect and collate feedback from communities affected by the Rohingya crisis. This summary aims to provide a snapshot of feedback received from Rohingya and host communities, to assist sectors to better plan and implement relief activities with communities’ needs and preferences in mind. The information in this edition includes insights from local Cox’s Bazar newspapers; as well as information collected through conversations with affected individuals, community focus group discussions and live radio phone-in programmes on Bangladesh Betar and Radio Naf, which are supported by UNICEF. The work is being delivered in partnership with IOM, the UN migration agency, and is funded by the UK Department for International Development. The Rohingya crisis: A dialogue Participants raised concerns about several issues during the programme. The main topics of discussion raised with the host community on their by local people were: challenges, worries and solutions • What measures government and development • Concerns that many school and college going agencies are taking to support host communities students are taking jobs with NGOs working as – participants felt they had also been heavily part of Rohingya response. The participants felt The Cox’s Bazar station of government radio affected by the Rohingya crisis. that this was having an impact on the overall broadcaster Bangladesh Betar is producing monthly education sector in Cox’s Bazar and wanted to • Concerns that teaching Bangla in camps may know the government’s plans to address this. -

Women's Livelihood Bangladesh

ASSESSMENT OF WOMEN’S LIVELIHOOD NEEDS IN THREE ECO-ZONES OF BANGLADESH UN Women Bangladesh House # CES (A) 11A, Road #113 Gulshan-2, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Phone: +88 02 985-8593 Fax :+88 02 9883828 www.unwomen.org MESSAGE The Royal Norwegian Embassy in Gender is a critical and overlooked Dhaka is proud to work closely dimension in climate policy together with UN Women to bring deliberations. I hope the knowledge the rights of women into the climate provided in this report will inspire change debate. We are glad to support a deeper appreciation for the vital the important project ‘Reducing significance of gender as an essential Vulnerability of Women Affected dimension in dealing with the social by Climate Change through Viable aspects of climate change. Livelihood Options’ here in Bangladesh. The women’s livelihood needs assessment report will help people select the appropriate livelihood Merete Lundemo adaptation modalities needed in Ambassador of Norway different adverse climatic situations. Dhaka I am pleased that the report provides concrete and applicable suggestions that will, I hope, prove helpful to people who need this expert advice now. © UN Women/2014 MESSAGE Bangladesh has achieved enormous This needs assessment was conducted to development gains over the last two decades investigate viable recommendations for and is set to achieve most of the millennium livelihood interventions, which can be carried development goals. The country has been out in an attempt to give women affected by particularly recognized for halving the number climate change and its impacts alternative of people living in poverty and for advances in livelihood options. -

Does Renewable Energy Increase Farmers' Well-Being? Evidence from Solar Irrigation Interventions in Bangladesh

Does Renewable Energy increase Farmers’ Well-being? Evidence from Solar Irrigation interventions in Bangladesh Monzur Hossain, Ph.D. Azreen Karim, Ph.D. Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) BIDS Research ALMANAC December 2nd, 2019 This presentation uses a free template provided by FPPT.com www.free-power-point-templates.com Outline • Background • SIPs: What is it good for? • Literature Review • Study Objective • Data & Sample Distribution • Methodology • Descriptive Statistics • Impact on rice production • Farmers’ Well-being: Contextualization • Conclusive & Policy remarks This presentation uses a free template provided by FPPT.com www.free-power-point-templates.com Background Green Infrastructure for Irrigations: An Overview of Solar Irrigation Projects (SIP) This presentation uses a free template provided by FPPT.com www.free-power-point-templates.com Solar power-based irrigation technology: what is it good for? • Access to Energy – SDG 7 • Clean Energy • Green Productivity • Farmers’ Well-being • Resilient Agriculture This presentation uses a free template provided by FPPT.com www.free-power-point-templates.com Literature Review • Suman (2018) - Impacts of solar irrigation pumps program in Andhra Pradesh and Chhattisgarh states of India. - Implementation of solar-powered irrigation system has grossly increased the income of the farmers. - Reduced the cost of irrigation and wastage of water and has caused a change in cropping pattern in some areas. - Due to the usage of the solar-powered irrigation system, the pressure on general electrical grid has lowered, resulting export of surplus power to the grid. - Increased both the quality and quantity of the crops. • Burney et al. (2016, 2010) • Garg (2018) - Implementation of solar-power irrigation systems can lead to greater economic well-being by reducing costs incurred for use of coal and diesel for irrigation. -

Wetland-Community Resilience to Flash Flood Hazards (Bonna) in Sunamganj District, Bangladesh

i Wetland-community resilience to flash flood hazards (Bonna) in Sunamganj district, Bangladesh By Mahed-Ul-Islam Choudhury A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of MASTER OF NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT Clayton H. Riddell Faculty of Environment, Earth and Resources Natural Resources Institute University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright ©2015 by Mahed-Ul-Islam Choudhury ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis research was to understand the recovery and resilience of wetland- community to flash flood disasters and its associated risks in the north-eastern part of Bangladesh. I conducted my study using a case study approach following an interdisciplinary research paradigm. It was found that wetland-community is extremely vulnerable to flash flood hazards - both in biophysical and social terms. However, they possess certain coping thresholds, and are resilient to disaster losses. The adaptive capacity of the local communities has been severely curbed by a number of socio-ecological, economic, and political factors, leading to natural resource degradation, marginalization and exclusion of the poor from common pool resources by powerful groups. Response capacities of local institutions were severely constrained by their limited relative autonomy. For building resilience, i) effective management and access of the poor to natural resources, and ii) enhancing autonomy of local institutions are required. iii Acknowledgement I take this opportunity to acknowledge all the supports I received from different individuals and institutions during the course of my thesis research. Without the support and cooperation from so many people and institutions this research would have not been possible. -

Aquaculture in Bangladesh

Annex 2 Methodology and Approach 1. Quantitative data assessment This section provides a short description of the main data set used for analysis in the Evaluation as well as an explanation of the quantitative data estimation approach pursued. Data availability For the analysis, the Evaluation has made use of quasi-experimental data set collected by independent survey teams as part of recent Mid-Term Evaluations of the Agricultural Extension Component (AEC) and the Re- gional Fisheries and Livestock Development Component (RFLDC). An overview of the data set is presented in Table 1. The Evaluation decided mainly to make use of these two data set based on an initial screening of data quality and availability. Table 1: Overview of data set collected by AEC and RFLDC Mid-Term Evaluations AEC RFLDC Post-intervention data available for both participating Post-intervention data available for all out- and control village households. However, no before- come variables and recall baseline data for se- after estimates included. lected areas, both for a group of participating Not possible at the individual household level statisti- and control village households. cally to match the information with AEC baseline in- Barisal: 328 participating households and 108 formation from 20071. control households. 1,087 participating households and 222 control village Noakhali: 321 participating households and households. 103 control households. Totally, 1,309 households. Total of 649 participating households and 211 control households. Totally 860 households. AEC – Mid-Term Evaluation data Data for the AEC Mid-Term Evaluation were collected during February 2011 through a comprehensive questionnaire (survey instrument) covering a number of outcome variables as well as a series of control vari- able indicators for general household characteristics. -

Poverty and Power: Survival of the Poorest in Three Villages of West Bengal, India

POVERTY AND POWER: SURVIVAL OF THE POOREST IN THREE VILLAGES OF WEST BENGAL, INDIA ANTHONY BECK THESIS SUBMITTED FOR PhD SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1991 ProQuest Number: 10731307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the relation between power and poor people's agency. It does so through critical review of the literature on theories of poverty, and through a comparative analysis of three villages in two contrasting regions of West Bengal, India. Chapters two and three compare two theoretical approaches to poverty. Chapter two notes the connection between the ideology of poverty measurement in nineteenth century Britain and twentieth century India, and discusses mainstream literature on the Indian political economy which concentrates on the poor. The chapter locates a common theme in these two literatures, which are seen to conceptualise the poor as passive and lacking agency. Chapter three considers an alternative theoretical approach, that is literature concerning the dimension of human agency. -

Studies on Seafood Production Systems in the South-West Region of Bangladesh

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 15(1): 123–132, 2017 ISSN 1810-3030 Studies on seafood production systems in the South-west Region of Bangladesh M. R. Islam1*, M. M. Haque2 and M. M. Rahman2 1Department of Aquaculture, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Gazipur and 2Department of Aquaculture, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The present study was conducted to understand existing production system of shrimp and prawn (seafood) with gher1 farming in the south-western region of Bangladesh from January to March 2014. Three gher farming clusters in three Upazilas of Bagerhat district were selected to carry out this study to assess the fact above using focus group discussion, key informant interview, questionnaire survey, physical observation, and literature review. The study revealed that gher farming system has changed the cropping patterns dramatically. This diversified farming system produces prawn, carp fish, boro paddy, and vegetable in the field where only single crop of paddy was cultivated. Gher dikes were used to produce vegetables, fruits and the central part for rice cultivation. Whereas the whole water body (during monsoon) and canals (during dry season) were used to culture finfish and prawn. Farmers were mainly found to use commercial feed with a rare amount of homemade feed because of the availability of commercial feed. Most of their investment goes for buying feed, PL and were found to take loan with high interest from banks or depot owners. Decreased salinity due to siltation in Mongla river resulted in increased overall production. The evidence presented in the study confirms that gher farming system impacting positively in the south-west region of Bangladesh.