SPECIAL REPORT Understanding U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

Thank You, Father Kim Il Sung” Is the First Phrase North Korean Parents Are Instructed to Teach to Their Children

“THANK YOU FATHER KIM ILLL SUNG”:”:”: Eyewitness Accounts of Severe Violations of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in North Korea PPPREPARED BYYY: DAVID HAWK Cover Photo by CNN NOVEMBER 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Michael Cromartie Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chair Nina Shea Vice Chair Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Khaled Abou El Fadl Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Bishop Ricardo Ramirez Ambassador John V. Hanford, III, ex officio Joseph R. Crapa Executive Diretor NORTH KOREA STUDY TEAM David Hawk Author and Lead Researcher Jae Chun Won Research Manager Byoung Lo (Philo) Kim Research Advisor United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Anne Johnson, Director of Communications Christy Klaasen, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Mark Hetfield, Director, International Refugee Issues Eileen Sullivan, Deputy Director for Communications Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Robert C. Blitt, Legal Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Mindy Larmore, Policy Analyst Jacquelin Mitchell, Executive Assistant Tina Ramirez, Research Assistant Allison Salyer, Government Affairs Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Acknowledgements The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expresses its deep gratitude to the former North Koreans now residing in South Korea who took the time to relay to the Commission their perspectives on the situation in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and their experiences in North Korea prior to fleeing to China. -

A Closer Look at Cuba and Its Recent History of Proliferation Hearing Committee on Foreign Affairs House of Representatives

A CLOSER LOOK AT CUBA AND ITS RECENT HISTORY OF PROLIFERATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 26, 2013 Serial No. 113–79 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 82–946PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 17:13 Nov 21, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_WH\092613\82946 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. SCHNEIDER, Illinois RANDY K. -

China Perspectives, 52 | March-April 2004 Border Disputes Between China and North Korea 2

China Perspectives 52 | march-april 2004 Varia Border Disputes between China and North Korea Daniel Gomà Pinilla Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/806 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.806 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2004 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Daniel Gomà Pinilla, « Border Disputes between China and North Korea », China Perspectives [Online], 52 | march-april 2004, Online since 23 April 2007, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/806 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.806 This text was automatically generated on 28 October 2019. © All rights reserved Border Disputes between China and North Korea 1 Border Disputes between China and North Korea Daniel Gomà Pinilla EDITOR'S NOTE Translated from the French original by Peter Brown 1 The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have enjoyed relatively stable relations since they came into being in 1948 and 1949 respectively. The Korean War (1950-53) set the scene for future relations between Pyongyang and Peking, given that Chinese help was vital for the survival of Kim Il- Sung’s regime. Sino-North Korean relations experienced periods of great strain during the 1960s and 1970s, when the Sino-Soviet conflict divided the Communist bloc into pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese camps. However, Peking was able to take advantage of the internal and external problems of the DPRK to present itself as Pyongyang’s main friend faced with the pressures exerted by South Korea and the West―the USA inter alia―which occurred all the more easily after the collapse of the USSR. -

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

1 DEPARTMENT of the TREASURY Foreign Assets Control Office Actions Taken Pursuant to Executive Order 13551 AGENCY

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/12/2014 and available online at [4810-AL] http://federalregister.gov/a/2014-19012, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Foreign Assets Control Office Actions Taken Pursuant to Executive Order 13551 AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets Control, Treasury. ACTION: Notice. ------------------- SUMMARY: The Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) is publishing the names of two entities whose property and interests in property are blocked pursuant to Executive Order 13551 of August 30, 2010, as well as the names of 18 vessels in which these entities have property interests. DATES: OFAC’s actions pursuant to Executive Order 13551 described in this notice were effective July 30, 2014. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Assistant Director, Compliance Outreach & Implementation, Office of Foreign Assets Control, Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC 20220, tel.: 202/622–2490. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Electronic and Facsimile Availability Additional information concerning OFAC is available from OFAC’s web site (www.treas.gov/ofac). Certain general information pertaining to OFAC’s sanctions 1 [4810-AL] programs is available via facsimile through a 24-hour fax-on demand service, tel.: 202/622–0077. Background On August 30, 2010, the President issued Executive Order 13551 (“Blocking Property of Certain Persons With Respect to North Korea”) (the “Order”). Section 1 of the Order blocks, with certain exceptions, all property and interests in property that are in the United States, that hereafter come within the United States, or that hereafter come within the possession or control of any United States person, including any foreign branch, of persons listed in the Annex to the Order, as well as persons determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of State, to meet any of the criteria set forth in subsection (a)(ii) of section 1. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

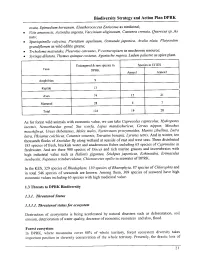

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S Mingyuegou Tumen Yanji Hunchun Onsong REPUBLIC OF KOREA RUSSIAN FEDERATION g n ia J Songjiang Chongsong ao rd Helong Kyonghung Kha Meihekou E sa Unggi n Fusong Erdaobaihe Hoeryong Quanyang Musan Najin Songjianghe Tumen Baishan Qingyuan Linjiang Samjiyon HAMGYONG- C Tonghua h N 'o BUKTO K a ng Paegam y na jin CHINA on m gs lu on a g Y Chasong Huch'ang Sinp'a Hyesan Myongch'on YANGGANG-DO Paek-am Manp'o Kapsan Nangnim Sindong- Kilchu nodongjagu Wiwon Kanggye CHAGANG-GO P'ungsan Honggul-li SEA OF Kuandian Ch'osan JAPAN Sup'ung Reservoir Ch'onch'on Kimch'aek Kop'ung Ch'angsong Pujon Koin-ni Changjin u Sakchu Tanch'on al Pukchin- Y Nodongjagu Pukch'ong Dandong Taegwam HAMGYONG- Iwon Uiju Huich'on Sinuiju NAMDO P'YONGAN-BUKTO Sinp'o Hyangsan Sinch'ang Kusong T'aech'on dong Tae Tonghae Hamhung Yongamp'o Kujang-up Sonch'on Yongbyon Pakch'on P'YONGAN- Chongp'yong Hungnam Yodok Chongju Kaech'on Tongjoson Man Anju NAMDO Yonghung Sunch'on Kowon P'yong-song Munch'on DEM. PEOPLE'S Sojoson Man Yangdog-up P'yongwon Wonsan REP. OF KOREA Chungsan-up P'yongyang Majon-ni I S Anbyon Onch'on - P'YONGYANG- T'ongch'on 'O Korea P SI n M Koksan i KANGWON-DO A Songnim j N m Hoeyang Bay Namp'o I Kuum-ni (Kosong) HWANGHAR- Sep'o Anak Sariwon BUKTO C Sohung h Ich'on HWANGHAE- ih Kumsong a P'yonggang -r National capital Changyon NAMDO P'yongsan i Kumhwa Provincial capital - Ch'orwon Monggump'o-r T'aet'an G n Sokch'o i Haeju N a Town, village SO h KAE k Ongjin SI u P Major airport Kaesong Ch'unch'on Sogang-ni Munsan International boundary Kangnung Demarcation Line Seoul REPUBLIC OF Provincial boundary KOREA Expressway YELLOW SEA Inch'on H a Main road n Wonju Secondary road Suwon Railroad 0 25 50 75 100 km The boundaries and names shown and the designations Ch'onan used on this map do not imply official endorsement or Sosan acceptance by the United Nations. -

Let Us Develop Ryanggang Province Into a Firm Base for Education in Revolutionary Traditions

LET US DEVELOP RYANGGANG PROVINCE INTO A FIRM BASE FOR EDUCATION IN REVOLUTIONARY TRADITIONS A Talk to Senior Officials of Ryanggang Province and Anti-Japanese Revolutionary Fighters July 21, 1968 Five years have passed since I visited Ryanggang Province in the company of the great leader. When I told him I was intending to make trip to Ryanggang Province, the leader said that he also wanted to go there once again but at that time he could not leave and if I would go there I must carefully investigate the state of the construc?tion work at the revolutionary battle sites. On my present tour of Ryanggang Province I have mainly inspect?ed the revolutionary battle sites in the Pochonbo and Samjiyon areas, as well as the historic places of the revolution along the River Amnok from Hyesan down to Huchang. While inspecting the revolutionary battle sites and historic sites in this province, I felt keenly again how great are the crimes com?mitted by the anti-Party, counter-revolutionary factionalists and their aftereffects. In the past these factionalists used to visit this province frequently and travelled about here, talking as though they were actively interested in developing the revolutionary battle sites, while submitting to the leader reports that the construction work on revolutionary battle sites was proceeding well. However, my recent inspections show that no special construction work on revolutionary battle sites and historic places has been carried out. Developing the revolutionary battle sites and historic places is very important work for preserving the memory of the great revolu?tionary feats performed by the leader in the days of the anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle, glorifying them for ever and educating Party members and other working people in our Party،¯s revolutionary tradi?tions. -

PK2019-12-OCR.Pdf

CONTENTS Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Climbs up Mt Paektu ....1 Δ Pyongyang Ostrich Farm ..................................................24 Δ Supreme Leader Gives Guidance to Various Units ..........2 Δ To Increase Aquatic Resources .........................................28 Δ Journey to Peace and Prosperity in 2019 .........................8 Δ Pyongyang Subway ..........................................................30 Δ Mountain Villages Transformed Δ Family of Teachers in Sohung .........................................34 beyond Recognition .........................................................20 Δ Children’s Paduk Contest Held ........................................36 Δ Hyesan-Samjiyon Railroad Opened ................................20 Δ Girl’s Dream Comes True ................................................38 Δ We Are Yearning for Your Benevolent Image .................22 Δ Reliving the Time-honoured History ................................40 FRONT COVER: Mt Paektu, the sacred mountain of the revolution Pictorial KOREA is published in Korean, Chinese, Russian and English. Photo: Kong Yu Il Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Climbs up Mt Paektu 1 Supreme Leader Gives Guidance to Various Units Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un visits Samjiyon County to provide fi eld guidance at the construction sites The Supreme Leader gives field guidance at the construction site of the Yangdok County hot spring resort that nears completion Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un continued his energetic guidance for the sake of the prosperity of the country and the -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

Operational Environment & Threat Analysis Volume 10, Issue 1 January - March 2019 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED OEE Red Diamond published by TRADOC G-2 Operational INSIDE THIS ISSUE Environment & Threat Analysis Directorate, Fort Leavenworth, KS Topic Inquiries: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Angela Williams (DAC), Branch Chief, Training & Support The Hermit Kingdom .............................................. 3 Jennifer Dunn (DAC), Branch Chief, Analysis & Production OE&TA Staff: North Korea Penny Mellies (DAC) Director, OE&TA Threat Actor Overview ......................................... 11 [email protected] 913-684-7920 MAJ Megan Williams MP LO Jangmadang: Development of a Black [email protected] 913-684-7944 Market-Driven Economy ...................................... 14 WO2 Rob Whalley UK LO [email protected] 913-684-7994 The Nature of The Kim Family Regime: Paula Devers (DAC) Intelligence Specialist The Guerrilla Dynasty and Gulag State .................. 18 [email protected] 913-684-7907 Laura Deatrick (CTR) Editor Challenges to Engaging North Korea’s [email protected] 913-684-7925 Keith French (CTR) Geospatial Analyst Population through Information Operations .......... 23 [email protected] 913-684-7953 North Korea’s Methods to Counter Angela Williams (DAC) Branch Chief, T&S Enemy Wet Gap Crossings .................................... 26 [email protected] 913-684-7929 John Dalbey (CTR) Military Analyst Summary of “Assessment to Collapse in [email protected] 913-684-7939 TM the DPRK: A NSI Pathways Report” ..................... 28 Jerry England (DAC) Intelligence Specialist [email protected] 913-684-7934 Previous North Korean Red Rick Garcia (CTR) Military Analyst Diamond articles ................................................