Penance and the Confessional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Centrality of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Christendom College

THE CENTRALITY OF THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AT CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE The Church teaches that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life”1 and that the celebration of the Mass “is a sacred action surpassing all others. No other action of the Church can equal its efficacy.”2 That is why “as a natural expression of the Catholic identity of the University. members of this community . will be encouraged to participate in the celebration of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, as the most perfect act of community worship.”3 Those central truths are taught and lived at Christendom College, a “Catholic coeducational college institutionally committed to the Magisterium”4 of the Church, in the following ways: The Celebration of the Sacred Liturgy The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass • Mass is offered frequently: twice daily Monday through Thursday, three times on MONDAY (Friday), twice on Saturday, and once on Sunday (the day on which we gather as one family). • Mass in the Roman Rite is celebrated in all the ways offered by the Church: in the Ordinary Form in both English and Latin, and in the Extraordinary Form from one to three times per week, as circumstances permit. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated with the solemnity appropriate to each feast, utilizing worthy sacred vessels and vestments, and drawing upon the Church’s rich tradition of chant, polyphony, and hymnody. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated reverently and with rubrical fidelity. • No classes or other activities are scheduled during Mass times. • The majority of the College community attends daily Mass regularly and with great devotion. -

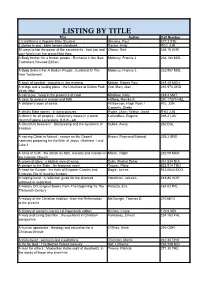

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

The Virtue of Penance in the United States, 1955-1975

THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Maria Christina Morrow UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2013 THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Chair _______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member Mary Ann Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology _______________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ Jana M. Bennett, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ William C. Mattison, III, Ph.D. Committee Member iii ABSTRACT THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation examines the conception of sin and the practice of penance among Catholics in the United States from 1955 to 1975. It begins with a brief historical account of sin and penance in Christian history, indicating the long tradition of performing penitential acts in response to the identification of one’s self as a sinner. The dissertation then considers the Thomistic account of sin and the response of penance, which is understood both as a sacrament (which destroys the sin) and as a virtue (the acts of which constitute the matter of the sacrament but also extend to include non-sacramental acts). This serves to provide a framework for understanding the way Catholics in the United States identified sin and sought to amend for it by use of the sacrament of penance as well as non-sacramental penitential acts of the virtue of penance. -

Guide to First Confession

Guide to First Confession Make a Good Examination of Conscience Read the “Suggestions for a Good Examination of Conscience” on the other side of this sheet. Confess Your Sins to the Priest Go into the confessional. You have the choice to kneel at the screen or sit to talk face-to-face with the priest. The priest should welcome you kindly and warmly. Make the Sign of the Cross, and say these words: Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. This is my first confession. These are my sins… Tell all your sins openly and honestly, including the number of times each sin was committed. Then, listen to the priest and follow his instructions. You may also ask any questions about the faith or how to grow in holiness. Pray the Act of Contrition when the priest tells you. ACT OF CONTRITION O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended You, and I detest all my sins, because I dread the loss of heaven and the pains of hell; but most of all because they offend You, my God, Who are all good and deserving of all my love. I firmly resolve, with the help of Your grace, to confess my sins, to do penance, and to amend my life. Amen. The priest will ask you to do a “penance,” usually some prayers, to show you are truly sorry for your sins. This is done after you return to your pew. If the priest assigns a good act, it should be done soon after you leave the church. -

Repentance, Penance, & the Forgiveness of Sins

REPENTANCE, PENANCE, & THE FORGIVENESS OF SINS Catholic translations of the Bible have often used the words “repentance” and “penance” interchangeably. Compare the Douay- Rheims Version with the New American Catholic Bible at Acts 2:38 and Acts 26:20 and you will see that these words (repentance & penance) are synonymous, words carrying the same meaning as the another. The Catholic Dictionary published by “Our Sunday Visitor”, a Catholic publication defines these words in the following ways: Repentance = Contrition for sins and the resulting embrace of Christ in conformity to Him. Penance or Penitence = Spiritual change that enables a sinner to turn away from sin. The virtue that enables human beings to acknowledge their sins with true contrition and a firm purpose of amendment. If there is any difference of meaning, I would suggest from pondering Greek definitions, that repentance (from the New Testament) 1 focuses on a change of heart, a change of mind and penance centers on the works of faith that this change of heart has produced. But both the change of heart and the works of faith go together; they are part of the same package. The Church has always taught that Christ’s death and resurrection brought reconciliation between God and humanity and that “the Lord entrusted the ministry of reconciliation to the Church.”1 The catechism teaches that because sin often wrongs the neighbor, while absolution forgives sin, “it does not remedy all the disorders sin has caused,”2 therefore the sinner must still recover his full spiritual health by doing works meet for repentance, that is, prove your repentance by what you do. -

The Role of a Confessional Seminary in Theological Education

EDITORIAL The Role of a Confessional Seminary in Theological Education Frank Bateman Stanger* "A confession" has been defined as "a formulary which com prises the articles of faith," "a creed to be assented to" as one re lates himself to a religious institution. A confessional school of theology is one that either is commit ted to an already formalized confession of faith, or which adheres to a system of theological doctrines which can logically be formal ized into a confession of the Christian faith. Such a seminary is committed to religious doctrines which are deemed to be consistent with historic Christianity and which are interpreted through a par ticular theological perspective. These basic doctrines become the springboard of all the institution's theological thinking in its efforts to be relevant. Such a confession of faith becomes the norm for the examination of all else. The significance of confessional theological education can be seen through four approaches: (1) the purpose of the theological seminary, (2) the predicament of contemporary theological education, (3) the pertinence of confessional theological education, (4) the potential of the theological seminary. THE PURPOSE OF THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY The fulfillment of the major objectives of theological education assumes a confessional approach to religious truth. These objec tives have a twofold relationship: to the church for which the theo logical seminary exists, and to the theological student himself as he prepares for Christian ministry. The Council on Theological Education of the United Presby- President, Asbury Theological Seminary. 4 The Asbury Seminarian terian Church in the U.S.A. has defined the function of theological education in relation to the Church in these words: The enterprise of theological education is an instru ment of the Church for the furtherance of its mission in the world. -

6. Confessional Subscription Robert Preus, Ph.D., D

FAITHFUL COMFESSI0Nt"P~LIFE IN THE CHURCH 6. Confessional Subscription Robert Preus, Ph.D., D. Theol. What is a Lutheran? What is the nature of subscription to the Lutheran Confessions? These two questions which are often considered together and which are as inseparably related as Siamese twins have become increasingly important in our day when Lutheranism is fighting for its identity and life. Today most of the Lutheran pastors and teachers throughout the world sub- scribe, at least pro forma, all the confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran church: the ancient catholic creeds and the great Lutheran confessions of the 16th century, i.e. the Augsburg Confession, the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Luther's two catechisms, the Smalcald Articles and the Formula of Concord. What does such subscription mean? Is such subscription any longer possible in our day of academic freedom and vaunted autonomy, ecu- menisin and dialogue? Many today think that subscription to any creed or confession is no longer viable and can represent only an impossible legalistic yoke upon an evangelical Christian or pastor. This is the conviction not only of Baptists and other traditionally non-credal denominations, but also of such renowned and conservative theologians as Karl Barth who holds that any human formulation of doctrine (as a creed or confession must be) is only a quest, an approximation, and therefore re1ative.l Are such objections valid? Is the Lutheran church able to justify con- fessional subscription today? And is she able to explain and agree on pre- cisely what is meant by such subscription? Today questions concerning the nature and spirit and extent of conies- sianal subscription have become a vexing problem, an enigma or even an embarrassment to many Lutherans. -

The Augsburg Confession and the Confessional Principle Churchman 94/4 1980

The Augsburg Confession and the Confessional Principle Churchman 94/4 1980 Robin A. Leaver In recent years Lutherans, particularly in America and Germany, have been re-examining their confessional inheritance. In 1977 the four hundredth anniversary of the compilation of the Formula of Concord was celebrated in a variety of ways. Not least was a succession of publications investigating the background of the document, its compilers, theology and later influence.1 The Formula was created in order to bring unity to the Lutheran churches which had been divided by various doctrinal controversies following Luther’s death in 1546. Although confessional in form, the Formula was not regarded as a replacement of the Augsburg Confession but rather as an amplification and clarification of certain doctrines implicit in the earlier confessional document. The formulators wrote: ‘Herewith we again whole-heartedly subscribe this Christian and thoroughly scriptural Augsburg Confession . And we do not intend . to depart from the aforementioned Confession or to set up a different and new confession.’2 Last year, 1979, the celebrations centred on the four hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the Diet of Speyer (1529) at which Lutherans presented their ‘Protest’, an action that earned for them the appellation ‘Protestant’.3 ‘In matters which concern God’s honour and the salvation and eternal life of our souls, every one must stand and give account before God for himself.’4 This protest led on to the confession of the following year. The year 1980 is a double -

(313 Duke Street) the BASILICA SCHOOL

July 4, 2021 The Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Very Rev. Edward C. Hathaway, Rector Rev. David A. Dufresne, Parochial Vicar Rev. Joseph B. Townsend, Parochial Vicar Rev. Noah C. Morey, In Residence Mr. Jordan Evans, Seminarian 310 South Royal Street + Alexandria, VA 22314 + 703.836.4100 + www.stmaryoldtown.org + [email protected] HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS All Masses are live streamed at www.stmaryoldtown.org SUNDAY 7 a.m., 8:30 a.m., 10 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. MONDAY through FRIDAY 6:30 a.m., 8 a.m. and 12:10 p.m. SATURDAY 8:30 a.m. and 5 p.m. (Vigil for Sunday) TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS 7:30 p.m., Third Friday of the month FEDERAL HOLIDAYS and HOLY DAYS Check the website and bulletin SACRAMENT OF PENANCE MONDAY through FRIDAY After 12:10 p.m. Mass WEDNESDAY 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. SATURDAY 9 to 10 a.m. and 4 to 5 p.m. Rosary Monday through Friday before 8 a.m. Mass BASILICA HOURS and on Saturday before 8:30 a.m. Mass MONDAY through FRIDAY 5:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Miraculous Medal Novena Monday 12 noon SATURDAY 7:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Wednesday 12:45 to 8:30 p.m. SUNDAY 6 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Adoration with Holy Hour & Benediction Wednesday 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. OFFICE HOURS (313 Duke Street) First Friday Nocturnal Adoration MONDAY through FRIDAY 9 a.m. -

January 12, 2020

The Baptism of our Lord — January 12, 2020 SAINT MARY’S & SAINT ELIZABETH’S CATHOLIC CHURCHES Phone: 701-579-4312 FATHER GARY BENZ-PASTOR [email protected]; Cell Phone 701-509-9504; Rectory 701-579-4874 VICTOR DVORAK –DEACON www.stmaryschurchnewengland.com “After Jesus was baptized, He came up from the water . .” There is an old story of a German cob- bler who used to sit in the doorway of his cottage and work at his trade. He was always singing or humming as he worked and most of his tunes were of a religious nature. One day, a Jewish merchant passed by and he was attracted by the cheerful appearance and the cheery song of the worker. “My friend,” remarked the Jew, “You seem exceedingly happy.” “I am,” remarked the cobbler, “I have good reason for it, since I am a King’s son.” The Jew continued on his way, thinking to himself that this guy was a mental case. Imagine, a peasant calling himself the son of a king! A few days later, the Jew passed the same cottage. “Good morning your royal highness,” was the Jew’s half scornful greeting. “Good morning,” said the cobbler. He continued, “I wonder if you believe that I am not the son of a king. Let me explain what I mean. As a Christian, I was baptized and Baptism makes one an adopted child of the King of heaven.” The Jew was so impressed that as he contemplated this in the following days and weeks, he eventually decided to seek Baptism and enter the Church. -

Rite of Penance Introduction

RITE OF PENANCE INTRODUCTION I The Mystery of Reconciliation in the History of Salvation 2 II The Reconciliation of Penitents in the Church’s Life 2 The Church is Holy but always in need of Purification 2 Penance in the Church’s Life and Liturgy 2 Reconciliation with God and with the Church 3 The Sacrament of Penance and Its Parts 3 a) Contrition 3 b) Confession 3 c) Act of Penance (Satisfaction) 3 d) Absolution 3 The Necessity and Benefit of the Sacrament 4 II Offices and Ministries in the Reconciliation of Penitents 4 The Community in the Celebration of Penance 4 The Minister of the Sacrament of Penance 4 The Pastoral Exercise of This Ministry 4 The Penitent 5 IV The Celebration of the Sacrament of Penance 5 The Place of Celebration 5 The Time of Celebration 5 Liturgical Vestments 5 A Rite for the Reconciliation of Individual Penitents 5 Preparation of Priest and Penitent 5 Welcoming the Penitent 5 Reading the Word of God 6 Confession of Sins and the Act of Penance 6 The Prayer of the Penitent and the Absolution by the Priest 6 Proclamation of Praise and Dismissal of the Penitent 6 Short Rite 6 B Rite for Reconciliation of Several Penitents with Individual Confession and Absolution 6 Introductory Rites 7 The Celebration of the Word of God 7 The Rite of Reconciliation 7 Dismissal of the People 8 C Rite for Reconciliation of Penitents with General Confession and Absolution 8 The Discipline of General Absolution 8 The Rite of General Absolution 8 V Penitential Celebrations 9 Nature and Structure 9 Benefit and Importance 9 VI Adaptations -

National Catholic Educational Association

SEMINARY JOURNAL VOlUme eighteeN NUmber ONe SPriNg 2012 Theme: Evangelization From the Desk of the Executive Director Msgr. Jeremiah McCarthy The New Evangelization and the Formation of Priests for Today Most Rev. Edward W. Clark, S.T.D. A Worldly Priest: Evangelization and the Diocesan Priesthood Rev. Matthew Ramsay For I Was a Stranger and You Welcomed Me Cardinal Roger Mahony Teaching Catechesis to Seminarians: A Fusion of Knowledge and Pedagogy Jim Rigg, Ph.D. International Priests in the United States: An Update Rev. Aniedi Okure, O.P. Emphasizing Relationality in Distance Learning: Looking toward Human and Spiritual Formation Online Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, O.P., and Sr. Paule Pierre Barbeau, O.S.B., Ph.D. Pastoral Ministry: Receiving Even While Giving Deacon James Keating, Ph.D. On a Dominican Vision of Theological Education Ann M. Garrido, D.Min. Priest as Catechetical Leader Diana Dudoit Raiche, Ph.D. Mountain Men: Preparing Seminarians for the Spiritual Trek Sr. Mary Carroll, S.S.S.F. Virtual Reality Requiring Real Virtue Msgr. Anthony J. Ireland, S.T.D. The Heart of the Matter Most Rev. Edward Rice Catholic Ministry Formation Enrollment: Statistical Overview for 2011-2012 Mary Gautier, Ph.D. BOOK REVIEW Life and Lessons from a Warzone: A Memoir of Dr. Robert Nyeko Obol by Robert Obol Reviewed by Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, O.P., Ph.D. National Catholic Educational Association The logo depicts a sower of seed and reminds us of the derivation of the word “seminary” from the Latin word “seminarium,” meaning “a seed plot” or “a place where seedlings are nurtured and grow.” SEMINARY JOURNAL VOLUME 18 NUMBER ONE SPRING 2012 Note: Due to leadership changes in the Seminary Department, this volume was actually published in April 2013.