The Evolution of the Tunic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Roslin – What Did People Wear?

Fact Sheet 4 Medieval Roslin – What did people wear? Roslin is in the lowlands of Scotland, so you would not see Highland dress here in the Middle Ages. No kilts or clan tartans. Very little fabric has survived from these times, so how do we find out what people did wear? We can get some information from bodies found preserved in peat bogs. A bit gruesome, but that has given us clothing, bags and personal items. We can also look at illustrated manuscripts and paintings. We must remember that the artist is perhaps making everyone look richer and brighter and the people being painted would have their best clothes on! We can also look at household accounts and records, as they often have detailed descriptions. So over the years, we have built up This rich noblewoman wears a patterned satin dress some knowledge. and a expensive headdress,1460. If you were rich, you could have all sorts of wonderful clothes. Soldiers returning from the crusades brought back amazing fabrics and dyes from the East. Trade routes were created and soon fine silks, satins, damasks, brocades and velvets were readily available – if you could afford them! Did you know? Clothing was a sign of your status and there • Headdresses could be very were “sumptuary laws“ saying what you could elaborate. Some were shaped and could not wear. Only the wives or daughters like hearts, butterflies and even of nobles were allowed to wear velvet, satin, church steeples! sable or ermine. Expensive head dresses or veils were banned for lower class women. -

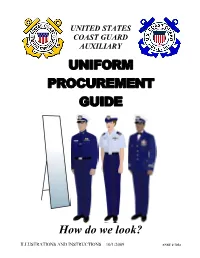

Uniform Procurement Guide

UNITED STATES COAST GUARD AUXILIARY UNIFORM PROCUREMENT GUIDE How do we look? ILLUSTRATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS – 10/1/2009 ANSC # 7053 RECORD OF CHANGES # DATE CHANGE PAGE 1. Insert “USCG AUXILIARY TUNIC OVERBLOUSE” information page with size chart. 19 2. Insert the Tunic order form page. 20 3. Replace phone and fax numbers with “TOLL FREE: (800) 296-9690 FAX: (877) 296-9690 and 26 1 7/2006 PHONE: (636) 685-1000”. Insert the text “ALL WEATHER PARKA I” above the image of the AWP. 4. Insert the NEW ALL WEATHER II OUTERWEAR SYSTEM information page. 27 5. Insert the RECEIPT FOR CLOTHING AND SMALL STORES form page. 28 1. Insert additional All Weather Parka I information. 26 2 11/2006 2. Insert All Weather Parka II picture. 27 1. Replace pages 14-17 with updated information. 14-17 3 3/2007 2. Insert UDC Standard Order Form 18 1. Change ODU Unisex shoes to “Safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes***” 4 4/2007 6, 8 2. Add a footnote for safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes 5 2/2008 1. Remove ODU from Lighthouse Uniform Company Inventory 25 1. Reefer and overcoat eliminated as outerwear but can be worn until unserviceable 6-10 6 3/2008 2. Remove PFD from the list of uniform items that may be worn informally 19 3. Update description of USCG Auxiliary Tunic Over Blouse Option for Women 21 1. Remove “Long”, “Alpha” and “Bravo” terminology from Tropical Blue and Service Dress Blue 7 6/4/2009 All uniforms 1. Sew on vendors for purchase of new Black “A” and Aux Op authorized 32 8 10/2009 2. -

Simple Viking Clothing for Men

Simple Viking Clothing for Men Being a guide for SCA-folk who desire to clothe themselves in a simple but reasonably accurate Viking fashion, to do honor to the reign of King Thorson and Queen Svava. Prepared by Duchess Marieke van de Dal This edition: 6/24/04 For further information, please don’t hesitate to email: [email protected] Copyright 2004, Christina Krupp Men’s Tunic Very little is known about the authentic cut of the Viking-Age men’s tunic.The Viborg shirt, below, is not typical in its complexity. Most likely, tunics were more like the first type shown. Generic Viking Men’s Tunic See Cynthia Virtue’s website, http://www.virtue.to/articles/tunic_worksheet.html for full instructions. A similar tunic worksheet website is from Maggie Forest: www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Tunics/TUNICS.HTML This tunic is very similar to Thora Sharptooth’s rendition of the Birka-style tunic, as described on her webpage, http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~capriest/viktunic.html 2.5 or 3 yds of 60” cloth works well for this layout. Most Viking tunics look best at knee-length. Underarm gussets are optional, but if they are omitted, make the upper arms roomy. Usually the bottom half is sufficiently full with this cut, but for extra fullness, add a gore of fabric in the center front and center back.You may also omit the side gores and leave the side seams unsewn from knee to mid-thigh. The Viborg Shirt The “Viborg Shirt” was found in Denmark, and is dated to the 11th C. -

Price List Best Cleaners 03-18.Xlsx

Price List Pants, Skirts & Suits Shirts & Blouses Pants Plain…………………………………………… 10.20 Business Shirt Laundered and Machine Pants, Silk/Linen…………………………………… . 12.30 Pressed (Men’s & Women’s)…… 3.60 Pants, Rayon/Velvet………………………………… 11.80 Pants Shorts………………………………………. 10.20 Chamois Shirt…………………………………………… 5.35 Skirts, Plain………………………………………… . 10.20 Lab Smock, Karate Top………………………………… . 7.30 Skirts, Silk, Linen………………………………….. 12.30 Polo, Flannel Shirt……………………………………… .. 5.35 Skirts, Rayon Velvet……………………………… .. 11.80 Sweat Shirt……………………………………………… . 5.70 Skirts Fully Pleated………………………………. 20.95 T-Shirt…………………………………………………… .. 4.60 Skirts Accordion Pleated………………………… . 20.95 Tuxedo Shirt……………………………………………… . 6.10 Suit 2 pc. (Pants or Skirt and Blazer)……………… 22.40.. Wool Shirt………………………………………………… . 5.35 Suit 3 pc. (Pants or Skirt Blazer & Vest)……………… 27.75. Suit, body suit………………………………………… 10.60. Blouse/Shirt, Cotton, Poly…………………………………… 9.50.. Suit, Jumpsuit…………………………………… 25.10 Blouse/Shirt, Rayon, Velvet………………………………… 11.10.. Sport Jacket, Blazer……………………………… .. 12.20 Blouse/Shirt, Silk, Linen……………………………………… 11.60 Tuxedo……………………………………………… . 22.95 Blouse/Shirt, Sleeveless……………………………………… 7.80 Vest………………………………………………… . 5.35 Dresses Outerwear Dress, Plain, Cotton, Wool, Poly, Terry, Denim…….. 19.00 Blazer, Sport Jacket……………………………… . 12.20 Dress,Silk, Linen …….………………………………. 23.20 Bomber Jacket………………………………….. 16.20 Dress,Rayon,Velvet …………………………………. 22.20 Canvas Field Coat………………………………… 16.20 Dress, 2-Piece, Dress & Sleeveless Jkt……………………… 27.60 Canvas Barn Jacket……………………………… -

Conflict in Yemen

conflict in yemen abyan’s DarkEst hour amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. first published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd Peter benenson house 1 easton street london Wc1X 0dW united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 31/010/2012 english original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: a building in Zinjibar destroyed during the fighting, July 2012. © amnesty international amnesty.org CONFLICT IN YEMEN: ABYAN’S DARKEST HOUR CONTENTS Contents ......................................................................................................................1 -

Ancient Civilizations Huge Infl Uence

India the rich ethnic mix, and changing allegiances have also had a • Ancient Civilizations huge infl uence. Furthermore, while peoples from Central Asia • The Early Historical Period brought a range of textile designs and modes of dress with them, the strongest tradition (as in practically every traditional soci- • The Gupta Period ety), for women as well as men, is the draping and wrapping of • The Arrival of Islam cloth, for uncut, unstitched fabric is considered pure, sacred, and powerful. • The Mughal Empire • Colonial Period ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS • Regional Dress Harappan statues, which have been dated to approximately 3000 b.c.e. , depict the garments worn by the most ancient Indi- • The Modern Period ans. A priestlike bearded man is shown wearing a togalike robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm bare; on his forearm is an armlet, and on his head is a coronet with a central circular decora- ndia extends from the high Himalayas in the northeast to tion. Th e robe appears to be printed or, more likely, embroidered I the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges in the northwest. Th e or appliquéd in a trefoil pattern. Th e trefoil motifs have holes at major rivers—the Indus, Ganges, and Yamuna—spring from the the centers of the three circles, suggesting that stone or colored high, snowy mountains, which were, for the area’s ancient inhab- faience may have been embedded there. Harappan female fi gures itants, the home of the gods and of purity, and where the great are scantily clad. A naked female with heavy bangles on one arm, sages meditated. -

Women in Pants: a Study of Female College Students Adoption Of

WOMEN IN PANTS: A STUDY OF FEMALE COLLEGE STUDENTS ADOPTION OF BIFURCATED GARMENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA FROM 1960 TO 1974 by CANDICE NICHOLE LURKER SAULS Under the direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst ABSTRACT This research presented new information regarding the adoption of bifurcated garments by female students at the University of Georgia from1960 to 1974. The primary objectives were to examine photographs of female students at the University of Georgia in The Pandora yearbooks as well as to review written references alluding to university female dress codes as well as regulations and guidelines. The photographs revealed that prior to 1968 women at UGA wore bifurcated garments for private activities taking place in dorms or at sorority houses away from UGA property. The study also showed an increase in frequency from 1968 to 1974 due to the abolishment of the dress code regulations. In reference to the specific bifurcated garments worn by female students, the findings indicated the dominance of long pants. This study offers a sample of the changes in women’s dress during the tumultuous 1960s and 1970s, which then showed more specifically how college women dressed in their daily lives across America. INDEX WORDS: Dress Codes, Mid Twentieth Century, University of Georgia, Women’s Dress WOMEN IN PANTS: A STUDY OF FEMALE COLLEGE STUDENTS ADOPTION OF BIFURCATED GARMENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA FROM 1960 TO 1974 by CANDICE NICHOLE LURKER SAULS B.S.F.C.S., The University of Georgia, 2005 B.S.F.C.S., The University of Georgia, 2007 -

General Ancient Greek Clothing Was Created by Draping One Or More Large Rectangles of Cloth Around the Body

Ancient Greek and Roman Clothing Information Sheet Greek Clothing: General Ancient Greek clothing was created by draping one or more large rectangles of cloth around the body. The cloth was woven by the women of the household, and the materials most often used were wool and linen. There were no set sizes to a piece of apparel. How the rectangles were draped, belted, and pinned determined how they fit the contours of the body and how they were named. When seen on statues or in painted pottery, the clothing often appears to be white or a single color. In actuality, the textiles used for clothing were often dyed in bright colors such as red, yel- low, green or violet. Decorative motifs on the dyed cloths were often either geometric patterns or patterns from nature, like leaves. Wide-brimmed hats were worn by men in bad weather or while traveling in the hot sun. When not letting their long hair fall in trailing curls on their backs or shoulders,Greek women put their hair up in scarves or ribbons. Depictions of men in paintings and statues also show them with filets (cloth headbands) around their heads. Though Greeks often went barefoot around the house, a variety of shoe styles were available, from sandals to boots. The sandals worn by the statue of Artemis shown in full view on the next page. Oedipus is dressed for travel in his wide-brimmed hat, cloak, and shoes. Note that the reclining man shown on this cup has put his shoes underneath A woman with her hair this couch and that the musician is wrapped in a scarf. -

Roman Clothing and Fashion

ROMAN CLOTHING AND FASHION ALEXANDRA CROOM This edition published 2010. This electronic edition published 2012. Amberley Publishing The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire GL5 4EP www.amberley-books.com Copyright © Alexandra Croom 2010, 2012 The right of Alexandra Croom to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-84868-977-0 (PRINT) ISBN 978-1-4456-1244-7 (e-BOOK) CONTENTS List of Illustrations Acknowledgements 1 - Introduction 2 - Cloths and Colour 3 - Men’s Clothing 4 - Women’s Clothing 5 - Children’s Clothing 6 - Beauty 7 - Provincial Clothing 8 - Conclusions Pictures Section Glossary References Weaving Terminology Bibliography LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS TEXT FIGURES 1 - The costume of goddesses 2 - Woman spinning 3 - Tunic forms 4 - A clothes press 5 - Tunics of the first and second centuries 6 - Tunics of the third and fourth centuries 7 - Tunic decorations 8 - Portrait of Stilicho 9 - Tunics 10 - Togas of the first to fourth centuries 11 - The ‘Brothers’ sarcophagus 12 - Togas of the fifth and sixth centuries 13 -

Sumptuary Legislation and Conduct Literature in Late Medieval England

SUMPTUARY LEGISLATION AND CONDUCT LITERATURE IN LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND Ariadne Woodward A thesis in the Department of History Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Ariadne Woodward, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ariadne Woodward Entitled: SUMPTUARY LEGISLATION AND CONDUCT LITERATURE IN LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to the originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _____________________________ Chair Dr. Barbara Lorenzkowski _____________________________ Examiner Dr. Nora Jaffary _____________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _____________________________ Supervisor Dr. Shannon McSheffrey Approved by: _____________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _____________________________ Dean of Faculty iii ABSTRACT Sumptuary Legislation and Conduct Literature in Late Medieval England Ariadne Woodward This study is an examination of attempts to control dress in late medieval England. Concerns about dress expressed in sumptuary legislation and conduct literature were demonstrative of deeper anxieties about gender, class, status, the interrelationship between medieval contemporaries, nationhood and morality. Clothing was especially targeted because it was an important marker of status and of individuals' morals. However, the lack of evidence of enforcement of sumptuary legislation and the limited scope of this type of legislation demonstrates a certain ambivalence towards a strict control of what individuals wore. Clothing played an important role in social negotiations. Late medieval society was extremely hierarchical and yet these hierarchies were somewhat fluid, which was both a source of confusion and opportunity. -

Prices Listed Are Subject to Additional Charges Based on Color, Trim Detail, Fabric, and Special Handling

Price List Pants, Skirts & Suits Shirts & Blouses Pants Plain…………………………………………… 10.70 Business Shirt Laundered and Machine Pants, Silk/Linen…………………………………… . 12.80 Pressed (Men’s & Women’s)…… 3.70 Pants, Rayon/Velvet………………………………… 12.30 Pants Shorts………………………………………. 10.70 Chamois Shirt…………………………………………… 5.60 Skirts, Plain………………………………………… . 10.70 Lab Smock, Karate Top………………………………… . 7.65 Skirts, Silk, Linen………………………………….. 12.80 Polo, Flannel Shirt……………………………………… .. 5.60 Skirts, Rayon Velvet……………………………… .. 12.30 Sweat Shirt……………………………………………… . 6.00 Skirts Fully Pleated………………………………. 21.45 T-Shirt…………………………………………………… .. 4.85 Skirts Accordion Pleated………………………… . 21.45 Tuxedo Shirt……………………………………………… . 6.40 Suit 2 pc. (Pants or Skirt and Blazer)……………… 23.50.. Wool Shirt………………………………………………… . 5.60 Suit 3 pc. (Pants or Skirt Blazer & Vest)……………… 29.10. Suit, body suit………………………………………… 11.15. Blouse/Shirt, Cotton, Poly…………………………………… 9.95.. Suit, Jumpsuit…………………………………… 26.35 Blouse/Shirt, Rayon, Velvet………………………………… 11.55.. Sport Jacket, Blazer……………………………… .. 12.80 Blouse/Shirt, Silk, Linen……………………………………… 12.05 Tuxedo……………………………………………… . 24.10 Blouse/Shirt, Sleeveless……………………………………… 8.20 Vest………………………………………………… . 5.60 Dresses Outerwear Dress, Plain, Cotton, Wool, Poly, Terry, Denim…….. 19.95 Blazer, Sport Jacket……………………………… . 12.80 Dress,Silk, Linen …….………………………………. 24.15 Bomber Jacket………………………………….. 17.00 Dress,Rayon,Velvet …………………………………. 23.15 Canvas Field Coat………………………………… 17.00 Dress, 2-Piece, Dress & Sleeveless Jkt……………………… 29.00 Canvas Barn Jacket……………………………… -

Celtic Clothing: Bronze Age to the Sixth Century the Celts Were

Celtic Clothing: Bronze Age to the Sixth Century Lady Brighid Bansealgaire ni Muirenn Celtic/Costumers Guild Meeting, 14 March 2017 The Celts were groups of people with linguistic and cultural similarities living in central Europe. First known to have existed near the upper Danube around 1200 BCE, Celtic populations spread across western Europe and possibly as far east as central Asia. They influenced, and were influenced by, many cultures, including the Romans, Greeks, Italians, Etruscans, Spanish, Thracians, Scythians, and Germanic and Scandinavian peoples. Chronology: Bronze Age: 18th-8th centuries BCE Hallstatt culture: 8th-6th centuries BCE La Tène culture: 6th century BCE – 1st century CE Iron Age: 500 BCE – 400 CE Roman period: 43-410 CE Post (or Sub) Roman: 410 CE - 6th century CE The Celts were primarily an oral culture, passing knowledge verbally rather than by written records. We know about their history from archaeological finds such as jewelry, textile fragments and human remains found in peat bogs or salt mines; written records from the Greeks and Romans, who generally considered the Celts as barbarians; Celtic artwork in stone and metal; and Irish mythology, although the legends were not written down until about the 12th century. Bronze Age: Egtved Girl: In 1921, the remains of a 16-18 year old girl were found in a barrow outside Egtved, Denmark. Her clothing included a short tunic, a wrap-around string skirt, a woolen belt with fringe, bronze jewelry and pins, and a hair net. Her coffin has been dated by dendrochronology (tree-trunk dating) to 1370 BCE. Strontium isotope analysis places her origin as south west Germany.