Sumptuary Legislation and Conduct Literature in Late Medieval England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Medieval Roslin – What Did People Wear?

Fact Sheet 4 Medieval Roslin – What did people wear? Roslin is in the lowlands of Scotland, so you would not see Highland dress here in the Middle Ages. No kilts or clan tartans. Very little fabric has survived from these times, so how do we find out what people did wear? We can get some information from bodies found preserved in peat bogs. A bit gruesome, but that has given us clothing, bags and personal items. We can also look at illustrated manuscripts and paintings. We must remember that the artist is perhaps making everyone look richer and brighter and the people being painted would have their best clothes on! We can also look at household accounts and records, as they often have detailed descriptions. So over the years, we have built up This rich noblewoman wears a patterned satin dress some knowledge. and a expensive headdress,1460. If you were rich, you could have all sorts of wonderful clothes. Soldiers returning from the crusades brought back amazing fabrics and dyes from the East. Trade routes were created and soon fine silks, satins, damasks, brocades and velvets were readily available – if you could afford them! Did you know? Clothing was a sign of your status and there • Headdresses could be very were “sumptuary laws“ saying what you could elaborate. Some were shaped and could not wear. Only the wives or daughters like hearts, butterflies and even of nobles were allowed to wear velvet, satin, church steeples! sable or ermine. Expensive head dresses or veils were banned for lower class women. -

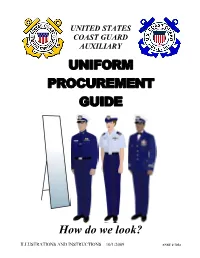

Uniform Procurement Guide

UNITED STATES COAST GUARD AUXILIARY UNIFORM PROCUREMENT GUIDE How do we look? ILLUSTRATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS – 10/1/2009 ANSC # 7053 RECORD OF CHANGES # DATE CHANGE PAGE 1. Insert “USCG AUXILIARY TUNIC OVERBLOUSE” information page with size chart. 19 2. Insert the Tunic order form page. 20 3. Replace phone and fax numbers with “TOLL FREE: (800) 296-9690 FAX: (877) 296-9690 and 26 1 7/2006 PHONE: (636) 685-1000”. Insert the text “ALL WEATHER PARKA I” above the image of the AWP. 4. Insert the NEW ALL WEATHER II OUTERWEAR SYSTEM information page. 27 5. Insert the RECEIPT FOR CLOTHING AND SMALL STORES form page. 28 1. Insert additional All Weather Parka I information. 26 2 11/2006 2. Insert All Weather Parka II picture. 27 1. Replace pages 14-17 with updated information. 14-17 3 3/2007 2. Insert UDC Standard Order Form 18 1. Change ODU Unisex shoes to “Safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes***” 4 4/2007 6, 8 2. Add a footnote for safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes 5 2/2008 1. Remove ODU from Lighthouse Uniform Company Inventory 25 1. Reefer and overcoat eliminated as outerwear but can be worn until unserviceable 6-10 6 3/2008 2. Remove PFD from the list of uniform items that may be worn informally 19 3. Update description of USCG Auxiliary Tunic Over Blouse Option for Women 21 1. Remove “Long”, “Alpha” and “Bravo” terminology from Tropical Blue and Service Dress Blue 7 6/4/2009 All uniforms 1. Sew on vendors for purchase of new Black “A” and Aux Op authorized 32 8 10/2009 2. -

Simple Viking Clothing for Men

Simple Viking Clothing for Men Being a guide for SCA-folk who desire to clothe themselves in a simple but reasonably accurate Viking fashion, to do honor to the reign of King Thorson and Queen Svava. Prepared by Duchess Marieke van de Dal This edition: 6/24/04 For further information, please don’t hesitate to email: [email protected] Copyright 2004, Christina Krupp Men’s Tunic Very little is known about the authentic cut of the Viking-Age men’s tunic.The Viborg shirt, below, is not typical in its complexity. Most likely, tunics were more like the first type shown. Generic Viking Men’s Tunic See Cynthia Virtue’s website, http://www.virtue.to/articles/tunic_worksheet.html for full instructions. A similar tunic worksheet website is from Maggie Forest: www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Tunics/TUNICS.HTML This tunic is very similar to Thora Sharptooth’s rendition of the Birka-style tunic, as described on her webpage, http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~capriest/viktunic.html 2.5 or 3 yds of 60” cloth works well for this layout. Most Viking tunics look best at knee-length. Underarm gussets are optional, but if they are omitted, make the upper arms roomy. Usually the bottom half is sufficiently full with this cut, but for extra fullness, add a gore of fabric in the center front and center back.You may also omit the side gores and leave the side seams unsewn from knee to mid-thigh. The Viborg Shirt The “Viborg Shirt” was found in Denmark, and is dated to the 11th C. -

Women's Clothing in the 18Th Century

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions A Peek Inside Mrs. Derby’s Clothes Press: Women’s Clothing in the 18th Century In the parlor of the Derby House is a por- trait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, wearing her finest apparel. But what exactly is she wearing? And what else would she wear? This edition of Pickled Fish focuses on women’s clothing in the years between 1760 and 1780, when the Derby Family were living in the “little brick house” on Derby Street. Like today, women in the 18th century dressed up or down depending on their social status or the work they were doing. Like today, women dressed up or down depending on the situation, and also like today, the shape of most garments was common to upper and lower classes, but differentiated by expense of fabric, quality of workmanship, and how well the garment fit. Number of garments was also determined by a woman’s class and income level; and as we shall see, recent scholarship has caused us to revise the number of garments owned by women of the upper classes in Essex County. Unfortunately, the portrait and two items of clothing are all that remain of Elizabeth’s wardrobe. Few family receipts have survived, and even the de- tailed inventory of Elias Hasket Derby’s estate in 1799 does not include any cloth- ing, male or female. However, because Pastel portrait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, c. 1780, by Benjamin Blythe. She seems to be many other articles (continued on page 8) wearing a loose robe over her gown in imitation of fashionable portraits. -

Price List Best Cleaners 03-18.Xlsx

Price List Pants, Skirts & Suits Shirts & Blouses Pants Plain…………………………………………… 10.20 Business Shirt Laundered and Machine Pants, Silk/Linen…………………………………… . 12.30 Pressed (Men’s & Women’s)…… 3.60 Pants, Rayon/Velvet………………………………… 11.80 Pants Shorts………………………………………. 10.20 Chamois Shirt…………………………………………… 5.35 Skirts, Plain………………………………………… . 10.20 Lab Smock, Karate Top………………………………… . 7.30 Skirts, Silk, Linen………………………………….. 12.30 Polo, Flannel Shirt……………………………………… .. 5.35 Skirts, Rayon Velvet……………………………… .. 11.80 Sweat Shirt……………………………………………… . 5.70 Skirts Fully Pleated………………………………. 20.95 T-Shirt…………………………………………………… .. 4.60 Skirts Accordion Pleated………………………… . 20.95 Tuxedo Shirt……………………………………………… . 6.10 Suit 2 pc. (Pants or Skirt and Blazer)……………… 22.40.. Wool Shirt………………………………………………… . 5.35 Suit 3 pc. (Pants or Skirt Blazer & Vest)……………… 27.75. Suit, body suit………………………………………… 10.60. Blouse/Shirt, Cotton, Poly…………………………………… 9.50.. Suit, Jumpsuit…………………………………… 25.10 Blouse/Shirt, Rayon, Velvet………………………………… 11.10.. Sport Jacket, Blazer……………………………… .. 12.20 Blouse/Shirt, Silk, Linen……………………………………… 11.60 Tuxedo……………………………………………… . 22.95 Blouse/Shirt, Sleeveless……………………………………… 7.80 Vest………………………………………………… . 5.35 Dresses Outerwear Dress, Plain, Cotton, Wool, Poly, Terry, Denim…….. 19.00 Blazer, Sport Jacket……………………………… . 12.20 Dress,Silk, Linen …….………………………………. 23.20 Bomber Jacket………………………………….. 16.20 Dress,Rayon,Velvet …………………………………. 22.20 Canvas Field Coat………………………………… 16.20 Dress, 2-Piece, Dress & Sleeveless Jkt……………………… 27.60 Canvas Barn Jacket……………………………… -

Making and Breaking Order Via Clothing

Making and breaking order via clothing Clothing regulation, cross-dressing, and the ordering mentality in later medieval and early modern England Brett Seymour A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of B.A. (Hons) in History University of Sydney 2012 Abstract Following the events which disrupted social stability in fourteenth and fifteenth-century England, individuals from a variety of social contexts demonstrated a particular necessity to see order visibly displayed in society. This thesis examines sumptuary regulations and cross- dressing side by side to demonstrate clothing's relationship to both making and breaking order. In the act of revealing this relationship, this thesis will argue that the two cases demonstrate clothing‘s importance in creating a visible confirmation of social order which ultimately brings to the surface an underlying collective ordering mentality that equated a sense of security with arranging everyone in society in their rightful place. Key words: order, mentality, sumptuary regulation, cross-dressing, clothing, early modern England, medieval England. Contents Chapter I Introduction: Order, disorder, and clothing in medieval English society .......................... 1 Order, disorder, and the response ........................................................................................... 4 Clothing and order .................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter II Making order via clothing: Clothing -

A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women's Mantle

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 14, No. 6, pp.188~203(2010) A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women’s Mantle * Lee Sangrye ‧ Kim Hyejeong Professor, Dept. of Fashion Design, TongMyong University * Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing Industry, Hankyong National University Abstract This study purposed to identify the design and composition characteristics of mantle through a historical review of its change and development focusing on women’s dress. This analysis was particularly focused on the Victorian age because the variety of mantle designs introduced and popularized was wider than ever since ancient times to the present. For this study, we collected historical literature on mantle from ancient times to the 19 th century and made comparative analysis of design and composition, and for the Victorian age we investigated also actual items from the period. During the early Victorian age when the crinoline style was popular, mantle was of A‐ line silhouette spreading downward from the shoulders and of around knee length. In the mid Victorian age from 1870 to 1889 when the bustle style was popular, the style of mantle was changed to be three‐ dimensional, exaggerating the rear side of the bustle skirt. In addition, with increase in women’s suburban activities, walking costume became popular and mantle reached its climax. With the diversification of design and composition in this period, the name of mantle became more specific and as a result, mantle, mantelet, dolman, paletot, etc. were used. The styles popular were: it looked like half-jacket and half-cape. Ornaments such as tassels, fur, braids, rosettes, tufts and fringe were attached to create luxurious effects. -

Conflict in Yemen

conflict in yemen abyan’s DarkEst hour amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. first published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd Peter benenson house 1 easton street london Wc1X 0dW united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 31/010/2012 english original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: a building in Zinjibar destroyed during the fighting, July 2012. © amnesty international amnesty.org CONFLICT IN YEMEN: ABYAN’S DARKEST HOUR CONTENTS Contents ......................................................................................................................1 -

Clothing in Ancient Greece Edited

Clothing in ancient Greece Clothing in ancient Greece and Rome was generally created out of large, single pieces of fabric. Several different pieces of clothing could be worn in various combinations to create multiple outfits. The fabric was also draped, belted and pinned into various styles. In art, it is sometimes very difficult to differentiate the various garments worn as they all seem to be billowy drapes of fabric. In Greece, women usually wore one of two garments on a regular basis. One was the peplos, a style of dress made from a single piece of fabric that is folded over at the top, wrapped around the body and pinned up at the shoulders. Folding down the top created a second layer of fabric that ran down the back and the front of the garment, which was referred to as an apoptygma. The other piece of clothing was worn by both men and women, and was called a chiton. The chiton was very similar to the peplos, except without the apoptygma. This was created by a single piece of fabric wrapped around the body and pinned up on the shoulders, or by two pieces of fabric sewn up both sides with space left for armholes. The men wore a shorter version of the chiton. This, too, could be belted or left as-is. The pins that were often used to hold up these garments worked very similarly to safety pins or brooches, and were called fibulae. The other important piece of clothing for both men and women was called the himation. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

Ancient Civilizations Huge Infl Uence

India the rich ethnic mix, and changing allegiances have also had a • Ancient Civilizations huge infl uence. Furthermore, while peoples from Central Asia • The Early Historical Period brought a range of textile designs and modes of dress with them, the strongest tradition (as in practically every traditional soci- • The Gupta Period ety), for women as well as men, is the draping and wrapping of • The Arrival of Islam cloth, for uncut, unstitched fabric is considered pure, sacred, and powerful. • The Mughal Empire • Colonial Period ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS • Regional Dress Harappan statues, which have been dated to approximately 3000 b.c.e. , depict the garments worn by the most ancient Indi- • The Modern Period ans. A priestlike bearded man is shown wearing a togalike robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm bare; on his forearm is an armlet, and on his head is a coronet with a central circular decora- ndia extends from the high Himalayas in the northeast to tion. Th e robe appears to be printed or, more likely, embroidered I the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges in the northwest. Th e or appliquéd in a trefoil pattern. Th e trefoil motifs have holes at major rivers—the Indus, Ganges, and Yamuna—spring from the the centers of the three circles, suggesting that stone or colored high, snowy mountains, which were, for the area’s ancient inhab- faience may have been embedded there. Harappan female fi gures itants, the home of the gods and of purity, and where the great are scantily clad. A naked female with heavy bangles on one arm, sages meditated.