Ambedkar and After: the Dalit Movement in India As 145 the Bringer of a Total New World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ranchi, Jharkhand

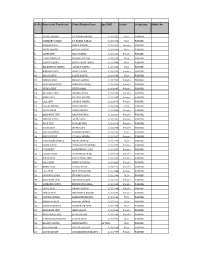

Sr. No. Name of the Beneficiary Father/Husban Name Age/DOB Gender Occupation Mobile No. 1 SANIYA ORAON LT. CHAMU ORAON 1/1/1952 Male FARMER 2 MAHADEV PAHAN LT. BARKA PAHAN 1/1/1953 Male FARMER 3 BUDHAN DEVI SUKRA MAHTO 1/1/1951 Female FARMER 4 SHIBU MAHTO JAY PAL MAHTO 1/1/1946 Male FARMER 5 SATMI DEVI FAGU MAHTO 1/1/1981 Female FARMER 6 CHATKU MAHTO JAGDISH MAHTO 1/1/1955 Male FARMER 7 GHATRI LOHRA SHITAL MANI LOHRA 1/1/1943 Male FARMER 8 BALESHWAR MAHTO GANDRU MAHTO 1/1/1954 Male FARMER 9 BUDHANI DEVI BIGAL PAHAN 1/1/1956 Female FARMER 10 BIGA MAHTO LALKU MAHTO 1/1/1948 Male FARMER 11 MANGRI DEVI BALDEV LOHRA 1/1/1956 Female FARMER 12 SAMUNDARI DEVI SUKH DEV LOHRA 1/1/1950 Female FARMER 13 SUKARI DEVI SEETU MAHO 1/1/1945 Female FARMER 14 BILASHRI DEVI DUKHU PAHAN 1/1/1966 Female FARMER 15 BINDI DEVI DHANSU MAHTO 1/1/1968 Female FARMER 16 LILA DEVI GANDRU MAHTO 1/1/1970 Female FARMER 17 VAGUN MUNDA DIBRU MUNDA 1/1/1935 Male FARMER 18 SUKARI DEVI VAGUN MUNDA 1/1/1950 Female FARMER 19 BANDHANI DEVI RAGHU MUNDA 1/1/1939 Female FARMER 20 SHUSHILS DEVI GAINU GOPE 1/1/1954 Female FARMER 21 FULO DEVI JAGRAM GOPE 1/1/2003 Female FARMER 22 KIRAN DEVI JATAN GOPE 1/1/1988 Female FARMER 23 MATAN MUNDA MANDRU MUNDA 1/1/1951 Male FARMER 24 KUSHAN DEVI CHARKA MUNDA 1/1/1937 Female FARMER 25 JAGESHWAR MAHTO HARKU MAHTO 1/1/1946 Male FARMER 26 URMILA DEVI VISHWANATH MUNDA 1/1/1982 Female FARMER 27 UGAN DEVI RAMESHWAR GOPE 1/1/1951 Female FARMER 28 JAYANTI DEVI CHANDAR MAHTO 1/1/1978 Female FARMER 29 KIRAN DEVI KALESHWAR GOPE 1/1/1979 Female FARMER 30 -

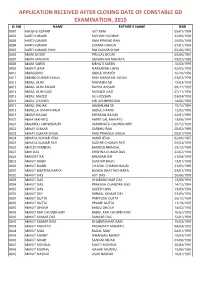

Application Received After Closing Date of Constable Gd Examination, 2015

APPLICATION RECEIVED AFTER CLOSING DATE OF CONSTABLE GD EXAMINATION, 2015 SL NO NAME FATHER'S NAME DOB 0001 AANSHU KUMAR AJIT RAM 05/01/1994 0002 AARTI KUMARI MOHAN DODRAY 22/08/1986 0003 AARTI KUMARI RAM PRASAD RAM 20/08/1998 0004 AARTI KUMARI SOMRA ORAON 07/01/1996 0005 AARTI KUMARI SHAH RAJ KUMAR SHAH 05/06/1992 0006 ABANI BOURI PIRULAL BOURI 05/06/1991 0007 ABANI MAHATA GUNADHAR MAHATA 03/05/1989 0008 ABANI SAREN BIBHUTI SAREN 10/03/1995 0009 ABANTI JENA NARASINGH JENA 02/05/1996 0010 ABBASUDIN ABDUL KHAYER 16/10/1994 0011 ABBIND KUMAR YADAV SHIV NARAYAN YADAV 03/03/1996 0012 ABDUL ALIM MAHASIN ALI 15/03/1995 0013 ABDUL ALIM ANSAR RAHIM ANSARI 09/11/1995 0014 ABDUL ALIM GAZI MOKSED GAZI 07/11/1994 0015 ABDUL MAZED ALI HOSSAIN 03/04/1996 0016 ABDUL OYAHED MD ACHHIRUDDIN 14/06/1990 0017 ABDUL RAJJAK ABUKALAM SK 15/12/1994 0018 ABDULLA OMAR FARUK ABDUL HAMID 12/05/1989 0019 ABDUR RAJJAK EKRAMUL RAJJAK 22/01/1997 0020 ABHA MAHATO AMRIT LAL MAHATO 13/06/1994 0021 ABHAIRAJ CHOWDHURY AMARNATH CHOWDHURY 20/12/1996 0022 ABHAY KUMAR SARBHU RAM 20/02/1995 0023 ABHAY KUMAR SINGH RAM PRAKASH SINGH 09/01/1994 0024 ABHAYA KUMAR JENA AMAR JENA 02/06/1997 0025 ABHAYA KUMAR PATI SUDHIR CHARAN PATI 05/04/1996 0026 ABHEEK MANDAL BAMDEB MANDAL 25/12/1995 0027 ABHI DAS KRISHNA KUMAR DAS 22/02/1994 0028 ABHIJEET RAI BHUWAN RAI 21/04/1995 0029 ABHIJIT BAGDI SUNDAR BAGDI 13/01/1993 0030 ABHIJIT BAURI CHANDI CHARAN BAURI 21/05/1993 0031 ABHIJIT BHATTACHARYA BIVASH BHATTACHARYA 03/01/1995 0032 ABHIJIT DAS AJIT DAS 26/06/1996 0033 ABHIJIT DAS DHARANIDHAR DAS -

Politics of Misrepresenting the Oppressed: a Critique of Abdus Samad’S Urdu Novel Dhamak*

mohammad sajjad Politics of Misrepresenting the Oppressed: A Critique of Abdus Samad’s Urdu Novel Dhamak* Abdus Samad (ʿAbduíṣ-Ṣamad) is known less as a teacher of political science and more as a famous Urdu fiction writer. Starting his literary career with short story writing, he later began writing novels. All five of his novels are accounts of the politics of twentieth-century Bihar. The first, Dō Gaz Zamīn (Two Yards of Land, 1988), deals with the politics of the partitions of the Indian subcontinent (first of India in 1947 and then the dismemberment of Pakistan in 1971) and depicts its impact on a declining Muslim feudal family of Bihar Shareef, roughly from the 1920s to the 1970s (Ghosh 1998, 1ñ40; Qasmi 2008, 24ñ26). It earned great praise from Urdu literary critics and in 1990 received the prestigious Sahitya Academy Award. His second novel Mahātmā (The Great Soul, 1992), the least appreciated of his novels critically, is a pessimistic account of the deep decline in the quality of higher education. His third novel, Khvābōñ kā Savērā (Dawn of Dreams, 1994), is the most critically acclaimed in terms of theme, technique, style, treatment, and so on. It deals with Muslims and their engagement with (or place in) the secular democracy of India in an increasingly communalized polity and society. In a quote appearing on the cover of his fourth novel Mahāsāgar (The Ocean, 1999), he is very explicit about why he gives primacy to the subject of politics in his writing. [Ö] in todayís life political factors have a deep impact since politics is no *I am thankful to Prof. -

Final Merit List, Bishath Batiya 2019-2020

FINAL MERIT LIST, BISHATH BATIYA 2019-2020 1 586 RADHA KUMARI UMESH KUMAR 1.4.1995 UR F 500 448 89.60 500 436 87.20 SCRT 1300 934 71.85 82.88 13009524 150 101 67.33 2 84.88 2 335 RAKESH KUMAR YADAV RAM SAGAR YADAV 7.1.1990 BC M 500 339 67.80 500 378 75.60 BSEB PATNA 2400 2100 87.50 76.97 202017448 150 109 72.67 4 80.97 3 679 ANURADHA KUMARI SANTOSH SAH 7.9.1996 BC F 500 377 75.40 500 371 74.20 BSEB PATNA 2400 2057 85.71 78.43 202015212 150 90 60.00 2 80.43 4 587 SUDHA KUMARI UMESH KUMAR MAHTO 2.7.1999 BC F 600 513 85.50 500 378 75.60 SCERT 2300 1700 73.91 78.34 113005317 150 96 64.00 2 80.34 5 505 ARJUN KUMAR NAGENDRA SINGH 26.06.1983 BC M 700 485 69.29 900 725 80.56 BSEB PATNA 1600 1314 82.13 77.32 6201171139 147 81 55.10 2 79.32 6 156 RAKHI KUMARI BINOD KR. YADAV 5.6.1996 BC F 500 351.5 70.30 600 421.28 70.21 SERT DELHI 2300 1724 74.96 77.17 6204171178 142 89 62.68 2 79.17 7 621 PRASHANT KUMAR AJAY KUMAR MISHR 11.3.1978 UR (M) 900 677 75.22 900 615 68.33 BSEB PATNA 2400 2058 85.75 76.44 6301178240 147 97 65.99 2 78.44 8 617 KANHAIYA KR. -

Ppo No Name 172660 Sri Barjnandan Ray 120259 Sri R.L. Bawa 201611011224 Sri Chandra Madhaw Singh 201611061333 ी बबन र

PPO NO NAME 172660 SRI BARJNANDAN RAY 120259 SRI R.L. BAWA 201611011224 SRI CHANDRA MADHAW SINGH 201611061333 ी बबन राम 202334 RAM NANDAN SIGNH 239669 SIDH NATH SINGH 297483 SRI MUNDRIKA PRASAD S/83744 BRAHAMDEO YADAV 276300 RAJENDRA RAI 425254 BACHCHU SINGH 153495 BAGESH MISHRA 361158 MOHAN TIWARI 195762 SRI SATYA PAL SANE S/60538 LAKHANI SINGH 225402 DHARICHAN RAUT s/109823 PRAHLAD MANJHI 434271 LAKSHMAN SINGH 250098 SRI RATNESHWAR PRASAD 168240 ROY NATH RAM 116355 DARSHAN RAM 415091P ी BALIRAM HARIJAN S/116190 UPENDRA THAKUR 200912031871 LATE RAM LAGAN PRASAD 150789 ALAKH NR SHARMA 214993 SRI LAXMAN BAIDYA 424554 SRI VISHUN DEO YADAV 5158764 LATE GANESH PASAD MANDAL 225365 MADAN PRASAD 170260 SRI MAN MOHAN LAKRA 201611102142 SRI NAGENDRA KUMAR BHARTI 231880 JEEWACHH NR.JHA 133089 SRI KESHARI NANDAN TRIPAT s/27517 LT KHADERAN RAM 009045 vijay kumar singh 20181101111 ी वीर काश िसंह 284002 SADHU SHARAN LAL s/41285 LT. VISHWAMITRA TIWARY S/25294 LATE KAILASHPATI VERMA 134293 SRI RAM JANAM SINHA 1 248084 SHIVAJEE SINGH 212750 LATE BAL KRISHNA TIWARY 1344791 LATE RAM SWARUP MAHTO 226509 SHRI NANHKU RAM 235163 SRI BULAKI SINGH S/36632 LT.RAM BHOROSO PD 134842 N.V.V.KAMATH 101270 SRI. RAMIJANAM TIWARI s/41492 LATE RAMSHRINGAR RAM 201311124154 SRI DHARM DEO PRASAD YADAV BHR2987 SHRI ASHOK KUMAR 458632 SRI SHYAM BIHARI CHOUDHARY 200911151882 ी बु लाल िसंह 282780 DILIP KUMAR MUKHERJEE 201711011165 SRI SHANKAR SINGH 158042 KUSHESHWAR PANDEY 201711151017 ी राज कुमार दास 201411011330 ी गंगा शरण 141536071 anirud kumar 170593 RAVI BHUSHAN OJHA 248352 NEZAMUDDIN AHMAD NEZAMI 015005 shukhnand sah 296119 AMICHAND ROY 37104 ी BIR BAHADUR KUMAR S/7891 LT MAHESHWAR PD. -

West Zone Forest Land Sale Report

WEST ZONE FOREST LAND SALE REPORT VENDOR VENDEE FATHER/HUSBAND SL.NO. Anchal Name Mauja Name Thana No Khata No Plot No AREA Type Of Deed Deed No Volum No Page From Page To Book CATEGORY Year VENDOR NAME ADDRESS VENDEE NAME ADDRESS FATHER/HUSBAND NAME NAME Bhaduli Pipradih, Barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1108 32 Sale Deed 466 13 319 338 I H_HOLD 2012 Nageshwar Yadav Late Bilat Gope Shanti Devi Dharamnath Mahto ango, barkagaon, hazaribagh 1 Hazaribagh Bhaduli Pipradih, Barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1108 32 Sale Deed 467 13 339 358 I H_HOLD 2012 Nageshwar Yadav Late Bilat Gope Shanti Devi Dharamnath Mahto ango, barkagaon, hazaribagh 2 Hazaribagh bhaduli pipradih, barkagaon, ango tola singar saray, barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1108 6 Sale Deed 468 13 359 372 I DON 2012 Madheshwar Gope Late Bilat Gope Ganesh Mahto Late Tikan Mahto 3 hazaribagh hazaribagh ango tola ambatola, barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99/77 1108 9 Sale Deed 5813 172 503 518 I R_COM 2013 Md. Imtiyaz Ahmad Md. Karim Punam Devi Sitaram Ango Tola lukaiya, Barkagaon, Hazaribagh 4 hazaribagh Lt. Dhaneshwar G.V.K. Cole (Tokisud) Pvt. BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1651 95 Sale Deed 7082 180 473 508 I COMMIND_NH_RD 2009 Most. Nanki Ango, Barkagaon, Hazaribagh C.H. Kailasham C 218, Ashok Nagar, Road No. 2, Ranchi 5 Ganjhu Ltd.(Th-C.H.Dayanand) Lt. Dhaneshwar G.V.K. Cole (Tokisud) Pvt. BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1582 82 Sale Deed 7082 180 473 508 I COMMIND_NH_RD 2009 Most. Nanki Ango, Barkagaon, Hazaribagh C.H. Kailasham C 218, Ashok Nagar, Road No. -

List of 1833 Candidates Debarred by RRC/ECR in Last Four Recruitment

East Central Railway (Railway Recruitment Cell) Polson Complex, Digha Ghat, Patna – 11 Telephone No. 0612-2560029, 2560035 Website: www.rrcecr.gov.in Email: [email protected] Notice No. 02/2016 dated 08.02.2016 List of 1833 candidates debarred by RRC/ECR in last 4 recruitments (ENN-01/07 (Gr. ‘D’), RRC/ECR/Group-D/1/2010, RRC/ECR/GP1800/1/2012 & RRC/ECR/GP1800/1/2013 1833 Candidates were found indulged in arranging impersonation in the last 4 recruitments (Employment Notice No- 01/07 Gr.‘D’, RRC/ECR/Group- D/1/2010, RRC/ECR/GP1800/1/2012 & RRC/ECR/GP1800/1/2013). So in terms of Railway Board’s letter No. E(RRB)/2001/25/1 dt. 14.02.02 & E(RRB)/2004/16/6 dt. 02.02.05, 1833 candidates have been debarred by RRC/ECR from all RRBs/RRCs examination for life time on the ground of impersonation. This action has been taken after adverse report against them in forsensic examination (Finger Print Expert/ Government Examiner of Questionable Documents) and after giving them show cause notice. The concerned candidates have alredy been suitably informed through separate letters. The Employment Notice-wise break-up of candidates is as under: Sl.No Employment Notice No Number of candidates debarred 1 01/07 (Gr. ‘D’) 901 2 RRC/ECR/Group-D/1/2010 524 3 RRC/ECR/GP1800/1/2012 229 4 RRC/ECR/GP1800/1/2013 179 TOTAL 1833 Chairman Railway Recruitment Cell, East Central Railway Combined list of ( 901+524+229+179) Total-1833 candidates debarred for life by RRC/ECR pertaining to Employment Notice No. -

Land Reforms

©Copyright Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) Publisher Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) BSIDC Colony, Off Boring-Patliputra Road Patna – 800 013 (BIHAR) Phone : 0612-2265649 Fax : 0612-2267102 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.adriindia.org Printer The Offsetters (India) Private Limited Chhajjubagh, Patna-800001 Disclaimer This monograph may not reflect the views held by the Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) or any of its sister concerns. Usual disclaimers apply. Preface Land and Labour have been at the core of a ‘civilised’ human existence since the very beginning. While they have provided body to various other kinds of labour (other than working on land), they have been both an instrument as well as foundation of power systems outside the body of labour itself, be it in the form of a primitive tribal community or a feudal society or a modern state. In fact, an economic formation/system and its laws of motion are explained not only by the conditions of labour, but also by an interaction of these with the other elements of the property system, amongst which the essentials of the property system in land are found to be of paramount importance. Since the inception of political economy/economic thought, there has been a near consensus on the centrality of land in facilitating the well-being through economic transformation. In particular, at the current juncture, the importance of access to land for the rural masses in ensuring a decent livelihood in most developing countries/societies is generally acknowledged throughout the academia. The first chapter of this report titled ‘Current Agrarian Situation in Bihar’ tries to bring forth this relationship between the ‘access to land’ and ‘well-being of masses’ in Bihar. -

The Khairlanji Murders & India's Hidden Apartheid ANAND

** persistence «• The Khairlanji Murders & India's Hidden Apartheid ANAND TELTUMBDE This book exposes the gangrenous heart of Indian society. ARUNDHATI ROY © Anand Teltumbde's analysis of the public, ritualistic massacre of a dalit family in 21st century India exposes the gangrenous heart of our society. It contextualizes the massacre and describes the manner in which the social, political and state machinery, the police, the mass media and the judiciary all collude to first create the climate for such bestiality, and then cover it up. This is not a book about the last days of relict feudalism, but a book about what modernity means in India. It discusses one of the most important issues in contemporary India. —ARUNDHATI ROY, author of The God of Small Things This book is finally the perfect demonstration that the caste system of India is the best tool to perpetuate divisions among the popular classes to the benefit of the rulers, thus annihilating in fact the efficiency of their struggles against exploitation and oppression. Capitalist modernization is not gradually reducing that reality but on the opposite aggravating its violence. This pattern of modernization permits segments of the peasant shudras to accede to better conditions through the over-exploitation of the dalits. The Indian Left must face this major challenge. It must have the courage to move into struggles for the complete abolition of caste system, no less. This is the prerequisite for the eventual emerging of a united front of the exploited classes, the very first condition for the coming to reality of any authentic popular democratic alternative for social progress. -

Office of the District & Sessions Judge, Supaul

Office of the District & Sessions Judge, Supaul Advertisement No- 01/2016 TABULATION CHART Roll No Name Fathrs/Husband Name Marks / Remarks 1 Bibhash Kr.Gupta Ram Varam Gupta 4 2 Vikash Kr. Singh Rameshwar Prassad 4 3 Ramesh Kr Roushan Ambika Sah 4 4 Md. Noor Alam Md. Ijhar 5 5 Ravi Kumar Vinay Kumar Karn 5 6 Rahul Kumar Vinay Kumar karn 5 7 Deepak Kumar Roy Suresh Roy 4 8 Guddu Kumar Singh Chandrama Singh 5 9 Ram Nath Kumar Prithivi Pasi 4 10 Shahansah Khan Asdhak Khan 5 11 Ramesh Kumar Yadav Sa|hdeo Yadav 4 12 Ajay Kumar Siyaram Choudhary ABS 13 Ajay Kumar Roy Laxman Roy Unstamped Envelope 14 Kusum Kumari Lal Babu Das 4 15 Mahesh Kumar Singh Hajari Prasad 4 16 Nikki Kumari Madan Kumar Jha 5 17 Rajesh Kumar Ishawar Chandra Das 4 18 Rakesh Kumar Biswas Akalesh Biswas Unstamped Envelope 19 Mahesh Paswan Niphikir Paswan 4 20 Sahani Kumar Bijay Kr Yadav ABS 21 Amit Kumar Chandrashekhar Ram 4 22 Silpa Kumari Badri Prasad Sah 4 23 Arjun Kumar Badri Prasad Sah 4 24 Harishankar Pandit Nand Lal Pandit 4 25 Nishikant Kumar Uma Nath Ojha ABS 26 Vikarm Kumar Late Umesh Ojha 5 27 Vijay Kumar Jha Birendra Jha 5 28 Juli Kumari Santosh Kumar Jha 5 29 Pravesh Paswan Shibu Paswan 4 1 30 Gopal Kumar Sahni Horil sahani ABS 31 Renu Kumari Ganga Prasad Rajak 4 32 Alok Prakash Chandra Prakash ABS 33 Balram Kumar Kishun Sharma 4 34 Dinesh Kumar Thakur Shankar Thakur 4 35 Navin Kumar Bindeshwari Pd. -

Roll No. Applicant's Name Address 16573 VILL

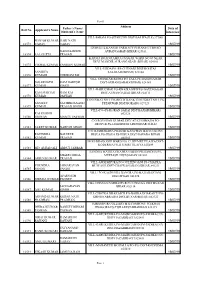

Sheet1 Address Father’s Name/ Date of Roll No. Applicant’s Name Husband’s Name Interview VILL-PARSIA PO-SITAKUND DIST-BALIYA(U.P) 277001 SHIVAM KUMAR HARI NATH 16573 YADAV YADAV 19/07/19 GURUKUL KANGRI FARMACY PURANI G.T.ROAD NAND KISHOR AURANGABAD BIHAR 824101 16574 LAL GUPTA PRASAD 19/07/19 KARMA ROAD RAMRAJ NAGAR WARD NO 07 NEAR DEVI MANDIR AURANGABAD (BIHAR) 824101 16575 VISHAL KUMAR SANJEEV KUMAR 19/07/19 VILL-URDA PO+PS-CHENARI DIST-ROHTAS SANGITA SASARAM(BIHAR) 821104 16576 KUMARI SHRIRAM PAL 19/07/19 VILL-SHANKAR BIGHA PO-SASA PS-DAUDNAGAR JAGARNATH RAM NARESH DIST-AURANGABAD(BIHAR) 824143 16577 KUMAR SINGH 19/07/19 VILL-HABUCHAK PO-KHAIRADWIP PS-DAUDNAGAR RAM SUBHAG RAM RAJ DIST-AURANGABAD BIHAR 824113 16578 KUMAR PASWAN 19/07/19 TENUGHAT NO 1 PO-RIGHT BANK TENUGHAT NO 1 PS- SANJEEV SACHHIDANAND PETARWAR DIST-BOKARO 829123 16579 KUMAR PRASAD SINGH 19/07/19 VILL+PO+PS-KORAN SARAI DIST-BAXAR(BIHAR) RAJ KISHOR 802126 16580 PASWAN MANTU PASWAN 19/07/19 C/O ROUSHAN KUMAR DEV AT KUSHMAHA PO- DEOPUR PS-JASIDIH DIST-DEOGHAR 814142 16581 SAKET KUMAR NARESH SINGH 19/07/19 C/O RAMRAKSHA PRASAD KANCHAN BAG COLONY RAVINDRA BALVEER HISUA PO-HISUA PS-HISUA DIST-NAVADA BIHAR 16582 KUMAR PRASAD 805103 19/07/19 MOH-BHADODIH WARD NO 17 JHUMRI TILAIYA DIST- KODERMA PO-JHUMRI TILAIYA 825409 16583 MD. AMJAD ALI ABDUL JABBAR 19/07/19 SANDHA MATHIA CHAPRA SARAN PO-SANDHA PS- SHATRUGHNA MUFFASIL DIST-SARAN 841301 16584 ARJUN KUMAR PRASAD 19/07/19 VILL-AWADHPURA PO-GULTENGANJ PS-CHAPRA VIJENDRA JAINARAYAN MUFFASIL DIST-CHAPRA(SARAN) BIHAR 841211 16585 -

2021072221.Pdf

TEACHERS RECRUITMENT PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST 2019-20 NAME OF BLOCK:- HARLAKHI CLASS:-I - V (GENERAL) PANCHAYAT :- KHIRHAR DISTRICT:-MADHUBANI CAST MALE/ MERIT TET TET TET SL REC MATRI TRAIN MERIT BOARD/UNIVERCITY NAME OF CANDIDATE FATHER/HUSBAND NAME D.O.B /CATE FAMEAL INTER TOTAL DIV. PERCE PERCE WEI ROLL REMARKS NO. NO. C ING POINT OF TRAINING GORY E NTAGE NTAGE TAGE NO 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 541 ANJALI ASHOK KUMAR 15/12/1999 GEN FEMALE 74.00 92.02 74.09 240.11 3.00 80.04 82.16 6.00 86.04 SCERT 112005824 2 91 GANGA KUMARI SHANKAR KUMAR SHAH 11-12-1996 EBC MALE 70.03 81.06 84.76 235.85 3.00 78.62 80.88 6.00 84.62 MP BOARD 12010049 3 602 RAKESH KUMAR YADAV RAM SAGAR YADAV 01-07-1990 BC MALE 67.08 75.06 87.05 229.19 3.00 76.40 80.96 6.00 82.40 BSEB PATNA 202017448 4 866 PRATIBHA CHOUDHARY DAYA SANKAR CHOUDHARY 06-02-1986 GEN FEMALE 85.66 82.05 65.00 232.71 3.00 77.57 79.72 4.00 81.57 OSMANIA UNIVERSITY 01715745 5 349 MANIRATNAM KUMAR MAHTO GHURAN MAHTO 02-04-1999 OBC MALE 80.40 63.80 87.45 231.65 3 77.22 79.33 4.00 81.22 BSEB PATNA 202005788 6 131 PANDAY THAKUR RAM KISHUN THAKUR 05-02-1987 EBC MALE 76.20 72.58 87.18 235.96 3 78.65 60.50 2.00 80.65 BSEB PATNA 6203171428 7 39 BIGHANESH KUMAR KUSHESHAWAR YADAV 15/08/1994 BC MALE 60.42 77.33 97.97 235.72 3.00 78.57 66.08 2.00 80.57 BSEB PATNA 6201178091 8 112 KANHAIYA KUMAR JHA PRADEEP JHA 04-10-1995 GEN MALE 77.80 72.60 78.84 229.24 3.00 76.41 78.41 4.00 80.41 LNMU DARBHANGA 107103641 9 789 MD MERAJ MD MAJLUM 10-02-1987 OBC MALE 64.66 77.67 86.05 228.38 3.00 76.13