Host Genetics and Infectious Disease: New Tools, Insights and Translational Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDF Patient & Family Handbook

Immune Deficiency Foundation Patient & Family Handbook for Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases This book contains general medical information which cannot be applied safely to any individual case. Medical knowledge and practice can change rapidly. Therefore, this book should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice. FIFTH EDITION COPYRIGHT 1987, 1993, 2001, 2007, 2013 IMMUNE DEFICIENCY FOUNDATION Copyright 2013 by Immune Deficiency Foundation, USA. REPRINT 2015 Readers may redistribute this article to other individuals for non-commercial use, provided that the text, html codes, and this notice remain intact and unaltered in any way. The Immune Deficiency Foundation Patient & Family Handbook may not be resold, reprinted or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission from the Immune Deficiency Foundation. If you have any questions about permission, please contact: Immune Deficiency Foundation, 110 West Road, Suite 300, Towson, MD 21204, USA; or by telephone at 800-296-4433. Immune Deficiency Foundation Patient & Family Handbook for Primary Immunodeficency Diseases 5th Edition This publication has been made possible through a generous grant from Baxalta Incorporated Immune Deficiency Foundation 110 West Road, Suite 300 Towson, MD 21204 800-296-4433 www.primaryimmune.org [email protected] EDITORS R. Michael Blaese, MD, Executive Editor Francisco A. Bonilla, MD, PhD Immune Deficiency Foundation Boston Children’s Hospital Towson, MD Boston, MA E. Richard Stiehm, MD M. Elizabeth Younger, CPNP, PhD University of California Los Angeles Johns Hopkins Los Angeles, CA Baltimore, MD CONTRIBUTORS Mark Ballow, MD Joseph Bellanti, MD R. Michael Blaese, MD William Blouin, MSN, ARNP, CPNP State University of New York Georgetown University Hospital Immune Deficiency Foundation Miami Children’s Hospital Buffalo, NY Washington, DC Towson, MD Miami, FL Francisco A. -

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Prof.Dr. TÜRKAN PATIROĞLU

Prof.Dr. TÜRKAN PATIROĞLU Kişisel Bilgiler WE-epbo:s that:t pt:u/r/[email protected]/rturkanp/ ETığpitati Yman Bdail gUizlmeranilık, Erciyes Üniversitesi, Dahili Tıp Bil., Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları, Türkiye 1998 - 2000 Tıpta UYazmndaanll ıUkz, mEracniylıeks, EÜrnciivyerss Üitnesivi,e Drsaihteilsi iT, Dıpa Bhiilli., TÇıopc Buikl. ,S Çaoğclıuğkı vSea ğHlaığsıt avleık Hlaarsıt, aTlüıkrlkairyı,e T 1ü9r7k7iy e- 11998828 - 1989 Yİnagbiliazcnec, Bı 2D Oilrltea rÜstü Sertifika, Kurs ve Eğitimler Sağlık ve Tıp, DEsesneenyt iHala Cylvinaniclaalr Rı Kesuellaarncıhm & S eGrCtiPfi kfoars ıT, Eriracli yInevse üsntiigvaetrosritse, sIni Hveasytvigaant oDre Anceaydleermi Yye, 2re0l1 E1tik Kurulu, 2008 Yaptığı Tezler STaıpğt.Va eU Hzmsta Andlık, 1, k9r8o2nik enfeksiyonu olan hastalarda glukoz metabolizması, Erciyes Üniversitesi, Tıp Fakültesi, Çocuk ASarğalışk tBırilimmlae rAi, lTaıpn, lDaarhıili Tıp Bilimleri, Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları, Pediatrik Hematoloji, Pediatrik İmmünoloji ve Allerji APrkoaf.Ddre.,m Erickiy Uesn Üvnaivnelrasirte /si ,G Töıpr Feavklüeltresi, Çocuk Sağ.Ve Hst Ad, 1995 - Devam Ediyor YDrodç..DDorç., .DErrc.,i yEersc iÜyensiv Üenrsiviteerssii, tTeıspi, FTaıpk üFlateksüil, tÇeosic, uÇko cSuakğ .VSaeğ H.Vset AHdst, 1A9d9, 01 9- 8179 9- 51989 Yönetilen Tezler UPAzmTIaRnOlıĞk,L CU.E TR.,K HAENM(OÖFğrİLeİn Aci )H, A20ST0A6LARINDA F8 GENİ İNT22H BÖLGESİNDEKİ İNVERSİYONUN ARAŞTIRILMASI., Tıpta DPAÜTZIERYOLĞELRUİ VTE., DTİESDSAEMVİİ NETEK İNİNTLRİAĞVİ.,A TSıKptÜaL UEzRm KaOnAlıkG,Ü ML.AKSAYROANK ÜGKELCİÜŞ(TÖİRğrİLenEcNi) H, 2A0Y0V4ANLARDA ADRENOMEDÜLLİN KPARTAINRİOAĞLL RUA TD.,Y UOZTUENR ASPÜİRNEİLNİ EYTAKŞİALYEARNİ, TLıÖpStaE MUzİLmİ aHnAlıSkT, HA.LMAeRhDmAe tE(NÖDğrOeKnRciİ)N, 2F0O0N4KSİYONLARIN DEĞERLENDİRİLMESİ SCI. I, SGSeCneI tvice A AnHalCysIi sİn odf eak Csolehroirnt eo fG 2i7re5n P aDtieerngtisl ewridthe H Yyapyeırn-IlgaEn Saynn Mdraokmaelse laenrd/or Chronic MFruecdoe cNu.,t aRnoejaosu-Rse Cstarnepdoid Ji.,a Csaisballero Garcia de Oteyza A., Buchta M., Huebscher K., Gamez-Diaz L., Proietti M., JSOaUghRaNfAi SL. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

2021 Code Changes Reference Guide

Boston University Medical Group 2021 CPT Code Changes Reference Guide Page 1 of 51 Background Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) was created by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1966. It is designed to be a means of effective and dependable communication among physicians, patients, and third-party payers. CPT provides a uniform coding scheme that accurately describes medical, surgical, and diagnostic services. CPT is used for public and private reimbursement systems; development of guidelines for medical care review; as a basis for local, regional, and national utilization comparisons; and medical education and research. CPT Category I codes describe procedures and services that are consistent with contemporary medical practice. Category I codes are five-digit numeric codes. CPT Category II codes facilitate data collection for certain services and test results that contribute to positive health outcomes and quality patient care. These codes are optional and used for performance management. They are alphanumeric five-digit codes with the alpha character F in the last position. CPT Category III codes represent emerging technologies. They are alphanumeric five-digit codes with the alpha character T in the last position. The CPT Editorial Panel, appointed by the AMA Board of Trustees, is responsible for maintaining and updating the CPT code set. Purpose The AMA makes annual updates to the CPT code set, effective January 1. These updates include deleted codes, revised codes, and new codes. It’s important for providers to understand the code changes and the impact those changes will have to systems, workflow, reimbursement, and RVUs. This document is meant to assist you with this by providing a summary of the changes; a detailed breakdown of this year’s CPT changes by specialty, and HCPCS Updates for your reference. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A. -

Novel Combined Immune Deficiency and Radiation Sensitivity Blended Phenotype in an Adult with Biallelic Variations in ZAP70 and RNF168

CASE REPORT published: 26 May 2017 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00576 Novel Combined Immune Deficiency and Radiation Sensitivity Blended Phenotype in an Adult with Biallelic Variations in ZAP70 and RNF168 Ivan K. Chinn1,2,3*†, Robert P. Sanders4†, Asbjørg Stray-Pedersen5,6,7, Zeynep H. Coban-Akdemir7,8, Vy Hong-Diep Kim9, Harjit Dadi9,10, Chaim M. Roifman9,10, Troy Quigg4, James R. Lupski1,7,8,11, Jordan S. Orange1,2,3 and I. Celine Hanson1,2 1 Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA, 2 Section of Immunology, Allergy, and Rheumatology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA, 3 Center for Human Immunobiology, Texas Children’s Edited by: Hospital, Houston, TX, USA, 4 Texas Transplant Institute, Methodist Hospital, San Antonio, TX, USA, 5 Norwegian National Andrew Gennery, Unit for Newborn Screening, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway, Newcastle University, UK 6 Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 7 Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA, 8 Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Reviewed by: Houston, TX, USA, 9 Division of Immunology and Allergy, Department of Pediatrics, The Hospital for Sick Children, University Filomeen Haerynck, of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 10 Canadian Centre for Primary Immunodeficiency, The Jeffrey Model Research Laboratory Ghent University, Belgium for the Diagnosis of Primary Immunodeficiency, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, Kohsuke Imai, 11 Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Japan *Correspondence: With the advent of high-throughput genomic sequencing techniques, novel genetic Ivan K. -

Glycophorins and the MNS Blood Group System: a Narrative Review

16 Review Article Page 1 of 16 Glycophorins and the MNS blood group system: a narrative review Genghis H. Lopez1,2, Catherine A. Hyland1,3, Robert L. Flower1,3 1Clinical Services and Research Division, Australian Red Cross Lifeblood, Kelvin Grove, Queensland, Australia; 2School of Medical Science, Griffith Health, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia; 3School of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Genghis H. Lopez, PhD. Clinical Services and Research Division, Australian Red Cross Lifeblood, 44 Musk Avenue, Kelvin Grove, Queensland 4059, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: The MNS blood group system, International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) 002, is second after the ABO system. GYPA and GYPB genes encode MNS blood group antigens carried on glycophorin A (GPA), glycophorin B (GPB), or on variant glycophorins. A third gene, GYPE, produce glycophorin E (GPE) but is not expressed. MNS antigens arise from several genetic mechanisms. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) contribute to the diversity of the MNS system. A new antigen SUMI (MNS50), p.Thr31Pro on GPA has been described in the Japanese population. Unequal crossing-over and gene conversion are the mechanisms forming hybrid glycophorins, usually from parent genes GYPA and GYPB. GYPE also contributes to gene recombination previously only described with GYPA. Recently, however, GYPE was shown to recombine with GYPB to form a GYP(B-E-B) hybrid. -

Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases in Children and Adults

Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases in children and adults Microorganism Primary Immune Deficiency Diseases Disease (PID) Environment Host • Background • Approach to diagnosis of PID • Genetic diagnosis of PID • Lack of focus is good thing • Looks like duck but not a duck Primary Immunodeficiency diseases • Inherited diseases of immune system • Affect different components of the immune system • Clinically heterogeneous Why do we need to diagnose PIDs? • Collective Prevalence of high as 1 in 10000 suggesting a very high burden of disease • Often missed causing significant morbidity and mortality • Multiple family members may get affected leading to financial burden on the family and society • Early diagnosis and adequate management can lead to significant reduction in morbidity and mortality Group Category Group I Combined immunodeficiencies Group II Combined immunodeficiencies with associated or syndromic features. Group III Predominantly antibody deficiencies. Group IV Diseases of immune dysregulation. Group V Congenital defects of phagocyte number, function, or both. Group VI Defects in innate immunity. Group VII Autoinflammatory disorders. Group VIII Complement deficiencies. Group IX Phenocopies of PID • International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS): • 354 distinct disorders • 344 different gene defects listed (Feb2017) Group I Combined immunodeficiencies Group IV Diseases of immune Group II Combined immunodeficiencies with dysregulation. associated or syndromic features. Group VII Autoinflammatory Group III Predominantly antibody disorders. -

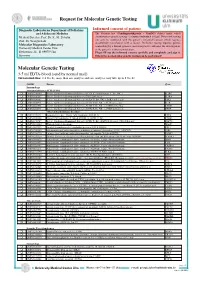

Molecular Genetic Testing

Request for Molecular Genetic Testing Diagnostic Laboratories Department of Pediatrics Informed consent of patient and Adolescent Medicine The German. law (Gendiagnostikgesetz – GenDG) defines under which Medical Director: Prof. Dr. K.-M. Debatin circumstances genetic testing of a human individual is legal. Diagnostic testing Prof. Dr. Georgia Lahr! can only be conducted with the patient’s informed consent which requires documented consultation with a doctor. Predictive testing requires genetic Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory! counselling by a human genetics specialist prior to and after the investigation, University Medical Center Ulm! or the patient’s written renunciation. Eythstrasse 24 - D-89075 Ulm Please fill out the informed consent carefully and completely and sign it. Germany Otherwise no molecular genetic testing can be performed! Molecular Genetic Testing 3-5 ml EDTA-blood (send by normal mail) Turnaround time: 2-4 weeks, more than one analysis and rare analyses may take up to 8 weeks OMIM Disease Gene Immunology Immunodeficiency SCID (T-B+) q OMIM 300400 Severe Combinined Immunodeficiency (SCID, X-chromosomal, T-, B+, NK- ) IL2RG q OMIM 606367 Severe Combinined Immunodeficiency, CD25 deficiency IL2RA q OMIM 600802 Severe Combinined Immunodeficiency (SCID, T-, B+, NK- ), JAK3 deficiency JAK3 q OMIM 608971 Severe Combinined Immunodeficiency (SCID, T- B+ NK+ ), IL7R deficiency IL7R q OMIM 608971 Severe Combinined Immunodeficiency (SCID, T- B+ NK+ ), CD3D deficiency CD3D q OMIM 608971 Severe Combinined Immunodeficiency (SCID, T- -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

Pulmonary Complications of Primary Immunodeficiencies

PAEDIATRIC RESPIRATORY REVIEWS (2004) 5(Suppl A), S225–S233 Pulmonary complications of primary immunodeficiencies Rebecca H. Buckley° Departments of Pediatrics and Immunology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA Summary In the fifty years since Ogden Bruton discovered agammaglobulinemia, more than 100 additional immunodeficiency syndromes have been described. These disorders may involve one or more components of the immune system, including T, B, and NK lymphocytes; phagocytic cells; and complement proteins. Most are recessive traits, some of which are caused by mutations in genes on the X chromosome, others in genes on autosomal chromosomes. Until the past decade, there was little insight into the fundamental problems underlying a majority of these conditions. Many of the primary immunodeficiency diseases have now been mapped to specific chromosomal locations, and the fundamental biologic errors have been identified in more than 3 dozen. Within the past decade the molecular bases of 7 X-linked immunodeficiency disorders have been reported: X-linked immunodeficiency with Hyper IgM, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, the Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, nuclear factor úB essential modulator (NEMO or IKKg), and the immune dysregulation polyendocrinopathy (IPEX) syndrome. The abnormal genes in X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) and properdin deficiency had been identified several years earlier. In addition, there are now many autosomal recessive immunodeficiencies for which the molecular bases have been discovered. These new advances will be reviewed, with particular emphasis on the pulmonary complications of some of these diseases. In some cases there are unique features of lung abnormalities in specific defects.