UT127 Liberty and Its Price Bklt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henryk Siemiradzki and the International Artistic Milieu

ACCADEMIA POL ACCA DELLE SCIENZE DELLE SCIENZE POL ACCA ACCADEMIA BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA E CENTRO BIBLIOTECA ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU FRANCESCO TOMMASINI, L’ITALIA E LA RINASCITA E LA RINASCITA L’ITALIA TOMMASINI, FRANCESCO IN ROME DELLA INDIPENDENTE POLONIA A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK CONFERENZE 145 ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA ISSN 0239-8605 ROMA 2020 ISBN 978-83-956575-5-9 CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK. ROMA 2020 Pubblicato da AccademiaPolacca delle Scienze Bibliotecae Centro di Studi aRoma vicolo Doria, 2 (Palazzo Doria) 00187 Roma tel. +39 066792170 e-mail: [email protected] www.rzym.pan.pl Il convegno ideato dal Polish Institute of World Art Studies (Polski Instytut Studiów nad Sztuką Świata) nell’ambito del programma del Ministero della Scienza e dell’Istruzione Superiore della Repubblica di Polonia (Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education) “Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” (National Programme for the Develop- ment of Humanities) - “Henryk Siemiradzki: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings” (“Tradition 1 a”, no. 0504/ nprh4/h1a/83/2015). Il convegno è stato organizzato con il supporto ed il contributo del National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage POLONIKA (Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kul- turowego za Granicą POLONIKA). Redazione: Maria Nitka, Agnieszka Kluczewska-Wójcik Recensione: Prof. -

After Robespierre

J . After Robespierre THE THERMIDORIAN REACTION Mter Robespierre THE THERMIDORIAN REACTION By ALBERT MATHIEZ Translated from the French by Catherine Alison Phillips The Universal Library GROSSET & DUNLAP NEW YORK COPYRIGHT ©1931 BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC. ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED AS La Reaction Thermidorienne COPYRIGHT 1929 BY MAX LECLERC ET CIE UNIVERSAL LIBRARY EDITION, 1965 BY ARRANGEMENT WITH ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 65·14385 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PREFACE So far as order of time is concerned, M. M athie( s study of the Thermidorian Reaction, of which the present volume is a translation, is a continuation of his history of the French Revolution, of which the English version was published in 1928. In form and character, however, there is a notable difference. In the case of the earlier work the limitations imposed by the publishers excluded all references and foot-notes, and the author had to refer the reader to his other published works for the evidence on which his conclusions were based. In the case of the present book no such limitations have been set, and M. Mathiei: has thus been able not only to state his con clusions, but to give the chain of reasoning by which they have been reached. The Thermidorian Reaction is therefore something more than a sequel to The French Revolution, which M. Mathiei:, with perhaps undue modesty, has described as a precis having no independent authority; it is not only a work of art, but a weighty contribution to historical science. In the preface to his French Revolution M. -

Legislative Assembly Approve Laws/Declarations of War Must Pay Considerable Taxes to Hold Office

Nat’l Assembly’s early reforms center on the Church (in accordance with Enlightenment philosophy) › Take over Church lands › Church officials & priests now elected & paid as state officials › WHY??? --- proceeds from sale of Church lands help pay off France’s debts This offends many peasants (ie, devout Catholics) 1789 – 1791 › Many nobles feel unsafe & free France › Louis panders his fate as monarch as National Assembly passes reforms…. begins to fear for his life June 1791 – Louis & family try to escape to Austrian Netherlands › They are caught and returned to France National Assembly does it…. after 2 years! Limited Constitutional Monarchy: › King can’t proclaim laws or block laws of Assembly New Constitution establishes a new government › Known as the Legislative Assembly Approve laws/declarations of war must pay considerable taxes to hold office. Must be male tax payer to vote. Problems persist: food, debt, etc. Old problems still exist: food shortages & gov’t debt Legislative Assembly can’t agree how to fix › Radicals (oppose monarchy & want sweeping changes in gov’t) sit on LEFT › Moderates (want limited changes) sit in MIDDLE › Conservatives (uphold limited monarchy & want few gov’t changes) sit on RIGHT Emigres (nobles who fled France) plot to undo the Revolution & restore Old Regime Some Parisian workers & shopkeepers push for GREATER changes. They are called Sans-Culottes – “Without knee britches” due to their wearing of trousers Monarchs & nobles across Europe fear the revolutionary ideas might spread to their countries Austria & Prussia urge France to restore Louis to power So the Legislative Assembly ………. [April 1792] Legislative Assembly declares war against Prussia and Austria › Initiates the French Revolutionary Wars French Revolutionary Wars: series of wars, from 1792-1802. -

Writers of the Time of National Partition on the Jasna Góra Pilgrimage Route

PEREGRINUS CRACOVIENSIS Zeszyt 3, 1996 ISBN 83−904441−5−1 / ISSN 1425−1922 Franciszek Ziejka Writers of the time of national Partition on the Jasna Góra pilgrimage route 1. At the feet of Saint Mary n January 4, 1842 Adam Mickiewicz, lecturing at the College de France described Jasna Góra as: “a famous place, known to all Slavs as the O destination of their pilgrimages, similar to Casa Santa of Loretto.”1 . Facts confirm the accuracy of these words. For more than six centuries now, one has observed a continuous flow of pilgrims on all roads leading to Częstochowa. The faithful from all over Poland as well as many other countries hurry there. Among them one can see the sick and the poor, children and students, miners and scholars, farmers and politicians. For centuries Poles, Czechs, Moravians, Slovaks, Hungarians, Croatians, Lithuanians and Russians have hastened there to meet at the foot of Saint Mary’s throne. The pilgrimages of Polish kings to Jasna Góra was one of the most beautiful Polish traditions dating back to the very first years of the Icon of the Mother of God’s presence in Częstochowa (it was probably brought here in 1382). Although we lack any written records directly confirming the visits of King Władysław Jagiełło (Ladislaus Jagiello) to Jasna Góra, historians believe that he made several pilgrimages to Częstochowa2 . It is worth mentioning that Jagiełło was not only the re−founder of the monastery at Jasna Góra (1393), but also a ruler who, in the year 1430, after learning of the raid on Jasna Góra and the destruction of the Holy Icon was ready to declare war on the Czechs, as Hussites were initially suspected of the attack. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

Political Economy in the Eighteenth Century: Popular Or Despotic? the Physiocrats Against the Right to Existence

Economic Thought 4.1: 47-66, 2015 Political Economy in the Eighteenth Century: Popular or Despotic? The Physiocrats Against the Right to Existence Florence Gauthier, Universite Paris, France [email protected] Abstract Control over food supply was advanced in the kingdom of France in the Eighteenth century by Physiocrat economists under the seemingly advantageous label of ‘freedom of grain trade’. In 1764 these reforms brought about a rise in grain prices and generated an artificial dearth that ruined the poor, some of whom died from malnutrition. The King halted the reform and re-established the old regime of regulated prices; in order to maintain the delicate balance between prices and wages, the monarchy tried to limit speculation in subsistence goods and achieved some success in regulating the provisioning of public markets. Le Mercier de la Rivière concluded that executing these reforms required more effective political control. After 1774 the new king gave the Physiocratic reforms a second chance, reforming property rights and establishing an aristocracy of the landed rich. Again, this led to price hikes and as a result so-called ‘popular emotions’ erupted. Turgot ordered military intervention to dispel the protesters, marking a first rupture between the monarchy and the people over speculation on subsistence. Turgot’s experiment failed and he was dismissed, but the Physiocracy had discovered that the market in subsistence offered new opportunities for economic power under the misleading legitimacy of ‘economic laws’. Turgot's followers, Dupont de Nemours and Condorcet, continued to develop this ‘theory’ that was later translated into a ‘scientific language’ that ultimately asserted the autonomy of the economic sphere and its alleged independence from ethics and politics. -

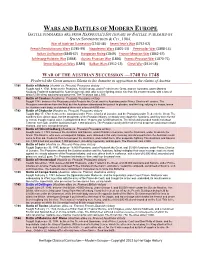

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Fiestas and Fervor: Religious Life and Catholic Enlightenment in the Diocese of Barcelona, 1766-1775

FIESTAS AND FERVOR: RELIGIOUS LIFE AND CATHOLIC ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE DIOCESE OF BARCELONA, 1766-1775 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrea J. Smidt, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Dale K. Van Kley, Adviser Professor N. Geoffrey Parker Professor Kenneth J. Andrien ____________________ Adviser History Graduate Program ABSTRACT The Enlightenment, or the "Age of Reason," had a profound impact on eighteenth-century Europe, especially on its religion, producing both outright atheism and powerful movements of religious reform within the Church. The former—culminating in the French Revolution—has attracted many scholars; the latter has been relatively neglected. By looking at "enlightened" attempts to reform popular religious practices in Spain, my project examines the religious fervor of people whose story usually escapes historical attention. "Fiestas and Fervor" reveals the capacity of the Enlightenment to reform the Catholicism of ordinary Spaniards, examining how enlightened or Reform Catholicism affected popular piety in the diocese of Barcelona. This study focuses on the efforts of an exceptional figure of Reform Catholicism and Enlightenment Spain—Josep Climent i Avinent, Bishop of Barcelona from 1766- 1775. The program of “Enlightenment” as sponsored by the Spanish monarchy was one that did not question the Catholic faith and that championed economic progress and the advancement of the sciences, primarily benefiting the elite of Spanish society. In this context, Climent is noteworthy not only because his idea of “Catholic Enlightenment” opposed that sponsored by the Spanish monarchy but also because his was one that implicitly condemned the present hierarchy of the Catholic Church and explicitly ii advocated popular enlightenment and the creation of a more independent “public sphere” in Spain by means of increased literacy and education of the masses. -

HSTR 352.01: French Revolution 1789-1848

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Summer 6-2016 HSTR 352.01: French Revolution 1789-1848 Linda S. Frey University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Frey, Linda S., "HSTR 352.01: French Revolution 1789-1848" (2016). Syllabi. 4242. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/4242 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Summer 2016 Prof. Frey FRENCH REVOLUTION Required Reading Wright, France in Modern Times Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the French Revolution Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled Rowe, “Civilians and Warfare during the French Revolutionary Wars.” (reserve) Holtman, The Napoleonic Revolution Walter, Diary of a Napoleonic Soldier Supplementary readings are available at the reserve desk at the Mansfield Library. Exams This class is only offered for a traditional grade. Midterm (tentative date June 8) will cover Wright pp. 3-56, Tocqueville, Rowe, Palmer, and readings on reserve. Final will cover Wright, pp. 57-122, Holtman, and Walter, and readings on reserve. Papers are due June 13 at the beginning of the class hour. No electronic submissions will be accepted. LATE PAPERS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED. Length: 5-7 pages double spaced. Style: Chicago Manual of Style, Footnotes. All papers should be submitted with the usual scholarly apparatus, that is, title page, footnotes, and bibliography. -

Tyranny Plagued the French Revolution

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Honors Theses Studies Spring 5-7-2020 Tyranny Plagued the French Revolution Christy Leigh Salinari Coastal Carolina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses Part of the Other Political Science Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Salinari, Christy Leigh, "Tyranny Plagued the French Revolution" (2020). Honors Theses. 369. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tyranny Plagued the French Revolution By Christy Leigh Salinari Political Science Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the HTC Honors College at Coastal Carolina University Spring 2020 Louis E. Keiner Kimberly Hurd Hale Director of Honors Assistant Professor HTC Honors College Political Science Edwards College of Humanities and Fine Arts ABSTRACT Liberty, equality, and fraternity were the three original pillars of the French Revolution at the start in 1789. The slogan became the rallying cry for the embittered French people in their initial pursuit for political and social transformation. The French Revolution is perhaps the most prominent contemporary illustration of a violent revolution which ultimately was successful, resulting in a model of democratic government. The French Revolution reached a decade in length wherein there were countless demonstrations, massacres, wars, civil unrest, and political enlightenment. -

Timeline (PDF)

Timeline of the French Revolution 1789 1793 May 5 Estates General convened in Versailles Jan. 21 Execution of Louis XVI (and later, Marie Jun. 17 National Assembly Antoinette on Oct. 16) Jun. 20 Tennis Court Oath Feb. 1 France declares war on British and Dutch (and Jul. 11 Necker dismissed on Spain on Mar. 7) Jul. 13 Bourgeois militias in Paris Mar. 11 Counterrevolution starts in Vendée Jul. 14 Storming of the Bastille in Paris (official start of Apr. 6 Committee of Public Safety formed the French Revolution) Jun. 1-2 Mountain purges Girondins Jul. 16 Necker recalled Jul. 13 Marat assassinated Jul. 20 Great Fear begins in the countryside Jul. 27 Maximilien Robespierre joins CPS Aug. 4 Abolition of feudalism Aug. 10 Festival of Unity and Indivisibility Aug. 26 Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen Sept. 5 Terror the order of the day Oct. 5 Adoption of Revolutionary calendar 1791 1794 Jun. 20-21 Flight to Varennes Aug. 27 Declaration of Pillnitz Jun. 8 Festival of the Supreme Being Jul. 27 9 Thermidor: fall of Robespierre 1792 1795 Apr. 20 France declares war on Austria (and provokes Prussian declaration on Jun. 13) Apr. 5/Jul. 22 Treaties of Basel (Prussia and Spain resp.) Sept. 2-6 September massacres in Paris Oct. 5 Vendémiare uprising: “whiff of grapeshot” Sept. 20 Battle of Valmy Oct. 26 Directory established Sept. 21 Convention formally abolishes monarchy Sept. 22 Beginning of Year I (First Republic) 1797 Oct. 17 Treaty of Campoformio Nov. 21 Berlin Decree 1798 1807 Jul. 21 Battle of the Pyramids Aug. -

Bread, Politics and Political Economy in the Reign of Louis Xv Archives Internationales D'histoire Des Idees

BREAD, POLITICS AND POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE REIGN OF LOUIS XV ARCHIVES INTERNATIONALES D'HISTOIRE DES IDEES INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVES OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS 86 STEVEN L. KAPLAN BREAD, POLITICS AND POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE REIGN OF LOUIS XV Directors: P. Dibon (Paris) and R. Popkin (Washington Univ., St. Louis) Editorial Board: J. Aubin (Paris)~ J. Collins (St. Louis Univ.)~ P. Costa bel (Paris)~ A. Crombie (Oxford) ~ I. Dambska (Cracow); H. de la Fontaine-Verway (Amsterda~); H. Gadamer (Heidelberg)~ H. Gouhier (Paris); T. Gregory (Rome)~ T.E. Jessop (Hull); P.O. Kristeller (Columbia Univ.)~ Elisabeth Labrousse (Paris); A. Lossky (Los Angeles); S. Lindroth (Upsala)~ J. Orcibal (Paris); I.S. Revaht (Paris); Wolfgang Rod (Miinchen); J. Roger (Paris); G.S. Rousseau (Los Angeles); H. Rowen (Rutgers Univ., N.J.); Ch. B. Schmitt (Warburg Inst. London); G. Sebba (Emory Univ., Atlanta); R. Shackleton (Oxford); J. Tans (Groningen); G. Tonelli (Binghamton, N.Y.). R' " D L A' T '_ TE I MER DIT' Plate 1. Map of France in the eighteenth century showing provinces and customs divisions. Necker, Compte-rendu (Paris, 1781). BREAD, POLITICS AND POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE REIGN OF LOUIS XV by STEVEN L. KAPLAN Volume One MARTINUS NIJHOFF - THE HAGUE - 1976 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN PUBLISHED WITH THE AI D OF A GRANT FROM THE HULL MEMORIAL PUBLICATION FUND OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY ~ 1976 by Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1976 A II rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this journal or parts thereof in any form ISBN-13: 978-94-010-1406-9 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-010-1404-5 001: 10.1007/978-94-010-1404-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE List of Illustrations IX Acknowledgements XI List of Abbreviations.