DAVID SKAGGS. TRANSCRIPT of OH 1903 This Radio Program Was Recorded for KGNU's “A Public Affair” Program and Aired In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DJ Playlist.Djp

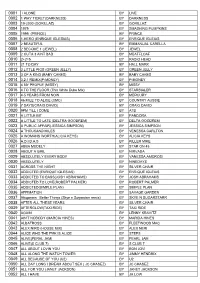

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

![PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8157/party-listening-music-by-tune-3628157.webp)

PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ]

[ PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ] 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 22 STEPS by Damien Leith 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A HARD RAIN'S A - GONNA FALL by Bryan Ferry And Roxy Music A LITTLE TOO LATE by Delta Goodrem {Karaoke} A NEW DAY HAS COME by Celine Dion {Karaoke} A PUBLIC AFFAIR by Jessica Simpson A THOUSAND MILES by Vanessa Carlton {Karaoke} A TOWN CALLED MALICE by The Jam ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE by Counting Crows {Karaoke} ADDICTED by Simple Plan {Karaoke} ADDICTED TO BASS by Puretone ADDICTED TO LOVE by Robert Palmer {Karaoke} ADDICTED TO YOU by Anthony Callea {Karaoke} ADVERTISING SPACE by Robbie Williams AIN'T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH by Jimmy Barnes ALL FOR YOU by Janet Jackson ALL I NEED IS YOU by Guy Sabastian {Karaoke} ALL I WANNA DO by Jo Jo Zep And The Falcons ALL I WANNA DO by Sheryl Crow {Karaoke} ALL MY LOVE by Led Zeppelin ALL NIGHT by Janet Jackson ALL NIGHT LONG by Lionel Richie ALL RIGHT NOW by Free {Karaoke} ALL SEATS TAKEN by Bec Cartright ALL THAT SHE WANTS by Ace Of Base {Karaoke} ALRIGHT by Supergrass ALWAYS BE WITH YOU by Human Nature AMAZING by Alex Lloyd {Karaoke} AMAZING by George Michael AMERICAN PIE by Don Mc Lean {Karaoke} AMERICAN PIE by Madonna AND SHE WAS by Talking Heads ANGEL by Amanda Perez {Karaoke} ANGEL by Shaggy {Karaoke} ANGEL EYES by Paulini {Karaoke} ANGELS BROUGHT ME HERE by Guy Sebastian {Karaoke} ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL by Pink Floyd {Karaoke} ANOTHER CHANCE by Roger Sanchez {Karaoke} -

The Sweet Taste of Forgiveness Catalog No

PENINSULA BIBLE CHURCH CUPERTINO THE SWEET TASTE OF FORGIVENESS Catalog No. 930 Luke 7:36-50 SERIES: PARABLES OF THE KINGDOM Sixth Message John Hanneman January 2, 1994 As we enter 1994 we return to a series of messages which we began and when she learned that He was reclining at the table in the last summer on the parables of Jesus from the gospel of Luke. We Pharisee’s house, she brought an alabaster vial of perfume, and will immerse ourselves once more in these marvelous, mysterious standing behind Him at His feet, weeping, she began to wet His texts which formed such a critical part of Jesus’ teaching ministry to feet with her tears, and kept wiping them with the hair of her his disciples. Our text today is Luke 7:36-50, the parable of the two head, and kissing His feet, and anointing them with the per- debtors. fume. Now when the Pharisee who had invited Him saw this, I want to begin this morning by quoting from a 1960’s song by he said to himself, “If this man were a prophet He would know Simon and Garfunkel. It is a rather short song but it is one that is who and what sort of person this woman is who is touching long on sadness: Him, that she is a sinner.” Time it was and what a time it was, And Jesus answered and said to him, “Simon, I have something It was…a time of innocence, a time of confidences. to say to you.” And he replied, “Say it, Teacher.” “A certain mon- Long ago…it must be…I have a photograph, eylender had two debtors: one owed five hundred denarii, and Preserve your memories, they’re all that’s left you. -

Singers News

Singers News Volume 3 Issue 8 August 2006 11612 S Western MAKE MONE Y WHILE GETTING DRUNK! Clarkson, Ain’t No Other Man by Christina Chicago, IL 60643 Stop in Beverly Records and pick up Aguilera, Crazy by Gnarls Barkley, Deja Vu by your free copy of Karaoke Nightlife. This 773-779-0066 Beyonce, Me & U by Cassie, Stars Are blind by publication lists hundreds of clubs that Paris Hilton, A Public Affair, by Jessica Simpson, have Karaoke Nights, many of these clubs Torn by Letoya, Do It To It by Cherish, So Sick offer cash prizes for best singers, some by Ne-Yo, Dani California by Red Hot Chili even give prizes for worst singer! Peppers, Let U Go by Ashley Parker Angel, Top 10 Beverly Records You High by James Blunt, Some Hearts by Carrie 1. Gnarls Barkley - Crazy PHM0906 Underwood, Over my Head by Fray, and What’s 2. Big & Rich - 8th of November CDSD0145 DID YOU KNOW? Left of Me by Nick Lachey. 3. Jewel - Good Day CDSD4609 Soundchoice offers custom made cds 4. Fergie - London Bridge PHM 1006 for only $5.00 per song! We have a couple new discs on Zoom, including 5. Dashboard Confessional - Don’t Wait CDSD4609 Beverly Records and Soundchoice have teamed 6. Black Eyed Peas - My Humps PSG1650 up for this unique service, compile your own a great rockabilly one from the early hits of 7. Jessica Simpson - A Public Affair CDSD4609 Johnny Cash. The instrumentation is fantastic! 8. James Blunt - You’re Beautiful THGP0604 karaoke disc using the Soundchoice catalog 9. -

Media All Jessica, All the Time Lacey Rose, 10.06.06, 8:30 AM ET If You're a Jessica Simpson Fan, You May Be Headed to the Theat

Media All Jessica, All The Time Lacey Rose, 10.06.06, 8:30 AM ET If you're a Jessica Simpson fan, you may be headed to the theaters this weekend to see her in Employee of the Month. But if you can't make it to Lionsgate's new movie, fear not: You can catch Simpson's song stylings on her new album, A Public Affair. Or you can find her at the newsstand--the 26-year-old is currently on the cover of Allure, but she's certain to be on the front of US Weekly, People or Star sometime soon. You can also buy her new line of "Hair U Wear" wigs. Or her "Dessert Beauty" line of edible "bath and body" treats. It's no secret that the old scarcity model of celebrity culture--regular people only got a glimpse of famous people, which made them want to see them that much more--vanished sometime in the CompuServe era. You can get as much access to Simpson and a slew of other instant stars as you want, whenever you want it. But if the customer is always right, Simpson and her ilk may be taking the wrong approach-- apparently you can get too much of a good thing. According to Encino, Calif.-based E-Poll Market Research, which ranks more than 2,800 celebrities on 46 different personality attributes, Simpson’s "overexposed" score went from 17% in September 2003 to 41% in mid-2006. (The average for most celebrities at the peak of their careers is between 3% and 7%.) During that same period, Simpson’s “talented” score dropped from 36% to a disappointing 28%. -

Search the Works

{ } = word or expression can't be understood {word} = hard to understand, might be this [Opening remarks missing] ... we have laid down in this course. It is not true that the truth has to be run -- has to run down in the circulation of thought. Most of you obstruct any circula- tion of thought. As far as you go, you will not enter the state of doubt or protest. You will go on playing. We have seen in the -- your -- in your own papers, you have dealt with people who had not -- no time to play and therefore again for- feited their own bliss, because they wanted to be serious too early. All these Ten Commandments in these papers -- in many of your papers, have been mistreated as though they were natural laws. So gentlemen, today I may -- must first make this statement: in the social science, there may be laws, but they are laws against which every one of us can trespass. As you well know, I have heard something about juvenile delinquen- ... [Tape interruption] ... and you don't want to hear this. You want to identify yourself with nature. And you are waiting for the gospel that will prove to you that sex and every- thing -- digestion, the choice of profession -- can be given you by aptitude tests; that is, by nature. That is, it is unexceptional that any man under certain circum- stances will act the same way. Every one of you knows that this isn't true. But you want to believe it, because you would like to disappear within a classifica- tion. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Title 1985 Bowling For Soup 2002 Anne-Marie 1 2 3 Len Berry 1 2 3 4 Feist 1 2 3 4 Sumpin New Coolio 17 (Seventeen) Mk 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 2 4 6 8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 2 Become 1 Jewel 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Find U Jewel 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 20th Century Boy T Rex 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 26 Cents Wilkinsons 48 Crash Suzi Quatro 5 4 3 2 1 Manfred Mann 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps 6345 789 Blues Brothers 68 Guns Alarm 7 Ways Abs 74 75 Connells 9 Crimes Damien Rice 99 Red Balloons Nena A and E Goldfrapp A Bad Dream Keane A Better Man Robbie Williams A Better Man Thunder A Big Hunk Of Love Elvis Presley A Boy From Nowhere Tom Jones A Brand New Me Dusty Springfield A Day In The Life Beatles A Deeper Love Aretha Franklin A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers A Different Corner George Michael A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley A Girl Like You Edwin Collins A Girl's Gotta Do Mindy Mccready A Good Heart Fergal Sharkey A Good Hearted Woman Waylon Jennings A Good Tradition Tinita Tikaram A Groovy Kind Of Love Mindbenders A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A House Is Not A Home Brook Benton A Kind Of Magic Queen A Kiss Is A Terrible Thing To Waste Meatloaf updated: March 2021 www.djdanblaze.com Can't Find one? Just ask DJ Dan Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Title A Kiss Is A Terrible Thing To Waste Meatloaf A Little Bit -

Papers on Parliament Number 66

Elections as Rituals: Private, Graeme Orr ∗ Communal and Public Introduction—ritual and aesthetics The area that we will traverse today falls within the law of politics. As a fairly new field, the law of politics hoovers up not just electoral law, but the rules governing parliaments, parties and money in politics. It mixes constitutional law, administrative issues and political science concerns, in equal parts. For the best part of two decades, I have been exploring the law of politics. It has been fun helping found a new sub- discipline. Ten years ago I paused from the labour of wading through statutes and case law, and wrote an essay called ‘The Ritual and Aesthetic in Electoral Law’.1 The essay was an attempt at a sociological understanding of elections as events, events we experience. Ten years later I turned the little tunes in that paper into a book titled Ritual and Rhythm in Electoral Systems.2 Its title prompted one wag to ask whether I was Catholic. (I am not. As we will see, the ‘ritual’ is secular and the ‘rhythm’ has nothing to do with the Billings method and everything to do with the way elections set up the seasons of politics). Today’s talk will distil some of the flavour of that book. Beyond thinking about elections, my overall theme is the importance of thinking about public institutions and practices in terms of how we experience them, and what meanings might be embedded in their forms and patterns. On the way to this forum I was reflecting on the charms of Canberra. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title +44 3 Doors Down 5 Stairsteps, The When Your Heart Stops Live For Today Ooh Child Beating Loser 50 Cent 10 Years Road I'm On, The Candy Shop Beautiful When I'm Gone Disco Inferno Through The Iris When You're Young In Da Club Wasteland 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Just A Lil' Bit 10,000 Maniacs Landing In London P.I.M.P. (Remix) Because The Night 3 Of Hearts Piggy Bank Candy Everybody Wants Arizona Rain Window Shopper Like The Weather Love Is Enough 50 Cent & Eminem & Adam Levine These Are Days 30 Seconds To Mars My Life 10CC Closer To The Edge My Life (Clean Version) Dreadlock Holiday Kill, The 50 Cent & Mobb Deep I'm Not In Love 311 Outta Control 112 Amber 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Peaches & Cream Beyond The Gray Sky 21 Questions U Already Know Creatures (For A While) 50 Cent & Ne-Yo 1910 Fruitgum Co. Don't Tread On Me Baby By Me Simon Says Hey You 50 Cent & Olivia 1975, The I'll Be Here Awhile Best Friend Chocolate Lovesong 50 Cent & Snoop Dogg & Young 2 Pac You Wouldn't Believe Jeezy California Love 38 Special Major Distribution (Clean Changes Hold On Loosely Version) Dear Mama Second Chance 5th Dimension, The How Do You Want It 3LW Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) 2 Pistols & Ray J No More Aquariuslet The Sunshine You Know Me 3OH!3 In 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Trust Me Last Night I Didn't Get To She Got It StarStrukk Sleep At All 21 Demands 3OH!3 & Ke$ha One Less Bell To Answer Give Me A Minute My First Kiss Stoned Soul Picnic 3 Doors Down 3OH!3 & Neon Hitch Up Up & Away Away From The Sun Follow Me Down Wedding Bell Blues Be Like That 3T 6 Tre G Behind Those Eyes Anything Fresh Citizen Soldier 4 Non Blondes 702 Duck & Run What's Up I Still Love You Here By Me 4 P.M. -

Visual Foxpro

12/31/2019 Please note, this music list does not include everything your DJ owns. If you don't see a certain song, no problem. Your DJ can get it for you. This is simply meant to be a helpful guide in selecting your music. Artist Title Artist Title Page 1 ALTERNATIVE ALTERNATIVE ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS FOUNTAINS OF WAYNE STACEY'S MOM ACE OF BASE THE SIGN FRANZ FERDINAND DO YOU WANT TO ALANIS MORISSETTE EVERYTHING FRANZ FERDINAND TAKE ME OUT ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC FRATELLIS CHELSEA DAGGER ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK YOU GAVIN DEGRAW CHARIOT ALL-AMERICAN REJECTS DIRTY LITTLE SECRET GAVIN DEGRAW FOLLOW THROUGH ALL-AMERICAN REJECTS MOVE ALONG GIN BLOSSOMS FOUND OUT ABOUT YOU ARCADE FIRE KEEP THE CAR RUNNING GIN BLOSSOMS HEY JEALOUSY ARCADE FIRE WE USED TO WAIT GOO GOO DOLLS BETTER DAYS ARCTIC MONKEYS BABY I'M YOURS GOO GOO DOLLS BLACK BALLOON ASHLEE SIMPSON BOYFRIEND GOO GOO DOLLS GIVE A LITTLE BIT AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED GOO GOO DOLLS IRIS AVRIL LAVIGNE GIRLFRIEND GOOD CHARLOTTE I JUST WANNA LIVE BARE NAKED LADIES IT'S ALL BEEN DONE GORILLAZ FEEL GOOD INC BARENAKED LADIES ANOTHER POSTCARD GRAND SKEEM BABY GOT BACK BARENAKED LADIES ONE WEEK GREEN DAY AMERICAN IDIOT BECK E-PRO GREEN DAY BASKET CASE BENNY BENASSI SATISFACTION GREEN DAY BOULEVARD OF BROKEN DREAMS BETTER THAN EZRA GOOD GREEN DAY WAKE ME UP WHEN SEPTEMBER ENDS BIG AUDIO DYMNAMITE THE GLOBE GREEN DAY WHEN I COME AROUND BLACK KEYS HOWLIN FOR YOU GRENDEL ZOMBIE NATION BLACK KEYS STRANGE TIMES GWEN STEFANI COOL BLESSED UNION HEY LEONARDO GWEN STEFANI RICH GIRL BLIND MELON NO -

“Unexpected Sources of Encouragement”

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 305 EAST MAIN STREET DURHAM , NC 27701 PHONE : (919) 682-5511 “Unexpected Sources of Encouragement ” A sermon by Mark E. Diehl 28th Sunday in Ordinary Time (Year C) October 6, 2013 Mark 12:41-44; Romans 12:1-13 It must be the season of Stewardship—all the scripture texts are about money these days! As Presbyterians, we remain fairly low-key about raising the budget and making a pledge. Financial and theological language is employed to make the approach more dignified, to appeal to the intellect, and by all means to keep it private. Do you know that in some religious communities, the giving of tithes and offerings is a public affair? Peoples’ pledges are published and announced for all to know. When the day comes for the annual campaign, the church service doesn’t end until the budget is met. The hat can get passed several times if not enough is raised! Such approaches would never work here, of course. We are too sophisticated for that. During Jesus’s day, giving was a public affair. As a matter of fact, it was such a spectacle that people gathered at the Temple to watch. Even Jesus was drawn to come and watch, according to our gospel text. Jesus posted himself across the courtyard from the collection box to watch with his disciples. Every family was expected to give, and sometime during the year, a representative from each family throughout the region of Judea would make a trip to the Temple with the family’s offering. 1 The collection boxes were placed in an area near the Temple where the general public was welcome—you didn’t have to be especially religious to contribute.