Harley E. Ryan, Jr.A, Qinxi Wub Aj. Mack Robinson College Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

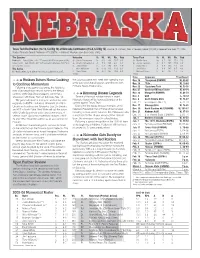

Huskers Return Home Looking to Continue

Texas Tech Red Raiders (13-12, 5-6 Big 12) at Nebraska Cornhuskers (16-8, 6-5 Big 12) • Game 25 • Lincoln, Neb. • Devaney Center (13,595) • Release Date: Feb. 17, 2006 Radio: Pinnacle Sports Network • TV: ESPN+ • Internet: Huskers.com (live radio, stats) The Coaches Nebraska Yr. Ht. Wt. Pts. Reb. Texas Tech Yr. Ht. Wt. Pts. Reb. Nebraska – Barry Collier, 282-217 overall, 86-85 in six years at NU G Jason Dourisseau Sr. 6-6 200 10.5 6.9 G Martin Zeno So. 6-5 202 15.2 5.6 Texas Tech – Bob Knight, 867-345 overall in 40 years, 103-56 in G Charles Richardson Jr. Jr. 5-9 160 4.0 3.2* G Jarrius Jackson Jr. 6-1 185 19.0 3.0* five seasons at TTU G Jamel White Fr. 6-3 180 6.8 1.8* F Darryl Dora Jr. 6-9 250 7.7 4.5 The Series F Wes Wilkinson Sr. 6-10 220 12.0 6.3 F Jon Plefka Jr. 6-8 245 6.5 4.3 NU leads series 12-8 after 84-68 loss in Lubbock in 2005. C Aleks Maric So. 6-11 265 10.4 8.0 F Michael Prince Fr. 6-7 205 2.5 2.5 *assists *assists Date Opponent Time/Result â â â Huskers Return Home Looking the Colorado game next week after spending most Nov. 18 ^Longwood (FSNMW) W, 80-65 of the past week handling prior commitments with Nov. 19 ^Yale W, 73-64 to Continue Momentum Pinnacle Sports Productions. -

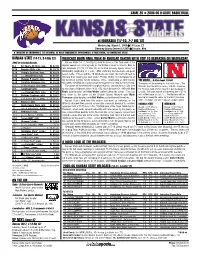

Kansas State Postgame Notes Vs. Texas

Contact: Tom Gilbert, Director of Men’s Basketball Communications Email:[email protected] | Phone: 785.532.7979/785.587.7868 www.kstatesports.com Twitter: @KStateMBB | Facebook: kstatesports | Instagram: KStateMBB KANSAS STATE POSTGAME NOTES VS. TEXAS Final Score: Texas 70, Kansas State 59 Records: Kansas State 9-18, 2-12 Big 12 // Texas 16-11, 6-8 Big 12 Attendance: 9,700 Next Game: Tuesday, Feb. 25 // at 1/1 Baylor (24-2, 13-1 Big 12) // 7 p.m. CT // Big 12 Now on ESPN+ Miscellaneous Notes • With the loss, K-State is now 1,669-1,174 all-time, in this, its 116th season of basketball. • K-State has now posted a 386-124 record at Bramlage Coliseum, including an 8-6 mark in 2019-20. • Head coach Bruce Weber is now 159-107 at K-State, 472-262 overall. • K-State’s 7-game losing streak is the longest of the Bruce Weber era and the longest for the Wildcats since dropping 7 in a row from Jan. 20-Feb. 14, 2001. • K-State still leads the all-time series, 22-18, with Texas, including 11-7 in Manhattan… With the win, Texas sweeps the season series for the first time since 2016 and now leads the series, 18-17, in the Big 12 era. • The Wildcats’ starting lineup consisted of junior David Sloan, junior Cartier Diarra, senior Xavier Sneed, freshman Antonio Gordon and senior Makol Mawien… This was the first time using this lineup and the eighth different lineup used this season, the most since 2014-15. -

2011-12 D-Fenders Media Guide Cover (FINAL).Psd

TABLE OF CONTENTS D-FENDERS STAFF D-FENDERS RECORDS & HISTORY Team Directory 4 Season-By-Season Record/Leaders 38 Owner/Governor Dr. Jerry Buss 5 Honor Roll 39 President/CEO Joey Buss 6 Individual Records (D-Fenders) 40 General Manager Glenn Carraro 6 Individual Records (Opponents) 41 Head Coach Eric Musselman 7 Team Records (D-Fenders) 42 Associate Head Coach Clay Moser 8 Team Records (Opponents) 43 Score Margins/Streaks/OT Record 44 Season-By-Season Statistics 45 THE PLAYERS All-Time Career Leaders 46 All-Time Roster with Statistics 47-52 Zach Andrews 10 All-Time Collegiate Roster 53 Jordan Brady 10 All-Time Numerical Roster 54 Anthony Coleman 11 All-Time Draft Choices 55 Brandon Costner 11 All-Time Player Transactions 56-57 Larry Cunningham 12 Year-by-Year Results, Statistics & Rosters 58-61 Robert Diggs 12 Courtney Fortson 13 Otis George 13 Anthony Gurley 14 D-FENDERS PLAYOFF RECORDS Brian Hamilton 14 Individual Records (D-Fenders) 64 Troy Payne 15 Individual Records (Opponents) 64 Eniel Polynice 15 D-Fenders Team Records 65 Terrence Roberts 16 Playoff Results 66-67 Brandon Rozzell 16 Franklin Session 17 Jamaal Tinsley 17 THE OPPONENTS 2011-12 Roster 18 Austin Toros 70 Bakersfield Jam 71 Canton Charge 72 THE D-LEAGUE Dakota Wizards 73 D-League Team Directory 20 Erie Bayhawks 74 NBA D-League Directory 21 Fort Wayne Mad Ants 75 D-League Overview 22 Idaho Stampede 76 Alignment/Affiliations 23 Iowa Energy 77 All-Time Gatorade Call-Ups 24-25 Maine Red Claws 78 All-Time NBA Assignments 26-27 Reno Bighorns 79 All-Time All D-League Teams 28 Rio Grande Valley Vipers 80 All-Time Award Winners 29 Sioux Falls Skyforce 81 D-League Champions 30 Springfield Armor 82 All-Time Single Game Records 31-32 Texas Legends 83 Tulsa 66ers 84 2010-11 YEAR IN REVIEW 2010-11 Standings/Playoff Results 34 MEDIA & GENERAL INFORMATION 2010-11 Team Statistics 35 Media Guidelines/General Information 86 2010-11 D-League Leaders 36 Toyota Sports Center 87 1 SCHEDULE 2011-12 D-FENDERS SCHEDULE DATE OPPONENT TIME DATE OPPONENT TIME Nov. -

History All-Time Coaching Records All-Time Coaching Records

HISTORY ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS CHARLES ECKMAN HERB BROWN SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT LEADERSHIP 1957-58 9-16 .360 1975-76 19-21 .475 4-5 .444 TOTALS 9-16 .360 1976-77 44-38 .537 1-2 .333 1977-78 9-15 .375 RED ROCHA TOTALS 72-74 .493 5-7 .417 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1957-58 24-23 .511 3-4 .429 BOB KAUFFMAN 1958-59 28-44 .389 1-2 .333 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1959-60 13-21 .382 1977-78 29-29 .500 TOTALS 65-88 .425 4-6 .400 TOTALS 29-29 .500 DICK MCGUIRE DICK VITALE SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT PLAYERS 1959-60 17-24 .414 0-2 .000 1978-79 30-52 .366 1960-61 34-45 .430 2-3 .400 1979-80 4-8 .333 1961-62 37-43 .463 5-5 .500 TOTALS 34-60 .362 1962-63 34-46 .425 1-3 .250 RICHIE ADUBATO TOTALS 122-158 .436 8-13 .381 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT CHARLES WOLF 1979-80 12-58 .171 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT TOTALS 12-58 .171 1963-64 23-57 .288 1964-65 2-9 .182 SCOTTY ROBERTSON REVIEW 18-19 TOTALS 25-66 .274 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1980-81 21-61 .256 DAVE DEBUSSCHERE 1981-82 39-43 .476 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1982-83 37-45 .451 1964-65 29-40 .420 TOTALS 97-149 .394 1965-66 22-58 .275 1966-67 28-45 .384 CHUCK DALY TOTALS 79-143 .356 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1983-84 49-33 .598 2-3 .400 DONNIE BUTCHER 1984-85 46-36 .561 5-4 .556 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1985-86 46-36 .561 1-3 .250 RE 1966-67 2-6 .250 1986-87 52-30 .634 10-5 .667 1967-68 40-42 .488 2-4 .333 1987-88 54-28 .659 14-9 .609 CORDS 1968-69 10-12 .455 1988-89 63-19 .768 15-2 .882 TOTALS 52-60 .464 2-4 .333 -

Basketball Media Guide Front Cover

Campbell University • Men’s Basketball 2009-2010 INSIDE CONTENTS CAMEL FACTS Campbell University ...................................................................................inside front cover Location ..........................................................................................................Buies Creek, N.C. John W. Pope Jr. Convocation Center/Gilbert Craig Gore Arena ................................2 Founded ...........................................................................................................January 5, 1887 Gore Arena Records .................................................................................................................... 4 2009-10 Roster ............................................................................................................................. 5 Enrollment .....................6834 (all campuses), 3034 (main campus undergraduate) 2009-10 Outlook/Q&A with Robbie Laing.......................................................................... 6 President ..............................................................Dr. Jerry M. Wallace (East Carolina, ‘56) Player Profi les ................................................................................................................................ 8 Director of Athletics .............................................Stan Williamson (Louisiana Tech, ‘85) Head Coach Robbie Laing ......................................................................................................26 Conference..............................................................................................Atlantic -

Fort Riley Soldiers Conduct Convoy Exercise

Priceless WWEDNESDAYEDNESDAY Take One VOLUME 15, NUMBER 74 WEDNESDAY,, MMARCH 14, 2007 WINNER OF THE KANSAS GAS SERVICE 2006 KANSAS PROFESSIONAL 2006 KANSAS PROFESSIONAL WINNER OF THE KANSAS PRESS EXCELLENCE IN EDITORIAL WRITING COMMUNICATORS PHOTO ESSAY AWARD COMMUNICATORS EDITORIAL AWARD ASSOCIATION ADVERTISING AWARD Park And Recreation Funds Pierzynski Named To Head Case Ends With Probation KSU’s Agronomy Department Gary Pierzynski has been named Ashland Bottoms and Rannell´s Editorial head of the Kansas By Jon A. Brake Flint Hills Prairie units. The latter is State University Department of devoted to range research. When the Riley County Police Agronomy - a post he has held on an Department and the Manhattan In addition, seven experiment interim basis for 14 months. fields located throughout eastern and City Manager were telling the Pierzynski, who is a professor of press, and the public that central Kansas are used to research soil and environmental chemistry specific soil-climate-cropping sys- $169,000 was missing from the and editor of The Journal of Manhattan Parks and Recreation tems for their respective areas. Environmental Quality, has been on During his time at K-State, Department, Riley County the faculty at K-State since 1989. Attorney Berry Wilkerson did not Pierzynski has taught classes on such “We are fortunate to have someone topics as plant nutrient sources, soil have the evidence. He could only with Gary´s credentials lead the find $700 missing from the fertility, environmental Department of Agronomy,” said Fred quality and soil and environmental department. Cholick, dean of K-State´s College Former Manhattan Parks and chemistry. -

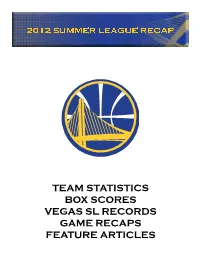

Team Statistics Box Scores Vegas Sl Records Game

TEAM STATISTICS BOX SCORES VEGAS SL RECORDS GAME RECAPS FEATURE ARTICLES WARRIORS FINAL SUMMER LEAGUE ROSTER WARRIORS SUMMER LEAGUE RESULTS NO PLAYER POS HT WT DOB PRIOR TO NBA/FROM NBA EXP. DATE OPPONENT RESULT SCORE HIGH POINTS/REBOUNDS/ASSISTS OPPS HIGH POINTS/REBOUNDS/ASSISTS July 13 vs. LA Lakers W 90-50 Thompson 24/Green 9/Thompson 5 Goudelock 14/Majok 7/Morris 4 40 Harrison Barnes F 6-8 210 5/30/92 North Carolina/USA R July 14 vs. Denver W 95-74 Jenkins 24/Barnes & Ezeli 7/Thompson 4 Hamilton 18/Faried 8/Faried 3 July 18 vs. Miami W 65-62 Jenkins 17/Barnes 7/Three Players 2 Cole 15/Viney 8/Cole 4 20 Kent Bazemore G/F 6-5 195 7/1/89 Old Dominion/USA R July 20 vs. Chicago W 66-57 Barnes 20/Green 11/Ragland 3 Teague & Thomas 12/Thomas 16/Four Players 2 25 Justin Burrell F 6-8 244 4/18/88 St. John’s/USA R July 21 vs. New Orleans W 80-72 Jenkins 15/Three Players 6/Jenkins 4 Henry 21/Thomas 8/Roberts 5 31 Festus Ezeli C 6-11 255 10/21/89 Vanderbilt/Nigeria R 23 Draymond Green F 6-7 230 3/4/90 Michigan State/USA R WARRIORS SUMMER LEAGUE STATS 22 Charles Jenkins G 6-3 220 2/28/89 Hofstra/USA 1 PLAYER G GS MIN FGM FGA PCT 3FGM 3FGA PCT FTM FTA PCT OFF DEF TOT AST PF DQ STL TO BLK PTS AVG Klay Thompson 2 2 59 14 27 .519 10 14 .714 3 4 .750 2 10 12 9 5 0 3 9 3 41 20.5 52 Dallas Lauderdale F 6-8 260 9/11/88 Ohio State/USA R Harrison Barnes 5 5 168 30 76 .395 8 14 .571 16 22 .727 10 18 28 2 11 0 9 7 0 84 16.8 21 Joe Ragland G 6-0 185 11/11/89 Wichita State/USA R Charles Jenkins 5 5 139 22 43 .512 0 2 .000 27 28 .964 0 7 7 14 6 0 8 14 0 71 14.2 -

Lista Dei Giocatori Disponibili

FANTA NBA 2015/2016: LISTA DEI GIOCATORI DISPONIBILI ATLANTA HAWKS Rondae Hollis-Jefferson A Iman Shumpert G Danilo Gallinari A Festus Ezeli C Lance Stephenson G Dennis Schroder G Thaddeus Young A J.R. Smith G Darrell Arthur A Marreese Speights C Pablo Prigioni G Jeff Teague G Thomas Robinson A James Jones G Devin Sweetney A Wesley Johnson G Justin Holiday G Willie Reed A Jared Cunningham G J.J. Hickson A HOUSTON ROCKETS Blake Griffin A Kent Bazemore G Andrea Bargnani C Joe Harris G Joffrey Lauvergne A Corey Brewer G Branden Dawson A Kyle Korver G Brook Lopez C Kyrie Irving G Kenneth Faried A Denzel Livingston G Chuck Hayes A Lamar Patterson G Matthew Dellavedova G Wilson Chandler A James Harden G Josh Smith A Shelvin Mack G CHARLOTTE BOBCATS Mo Williams G Jusuf Nurkic C Jason Terry G Luc Richard Mbah a Moute A Terran Petteway G Aaron Harrison G Quinn Cook G Nikola Jokic C K.J. McDaniels G Paul Pierce A Thabo Sefolosha G Brian Roberts G Anderson Varejao A Oleksiy Pecherov C Marcus Thornton G Cole Aldrich C Tim Hardaway Jr. G Damien Wilkins G Austin Daye A Patrick Beverley G DeAndre Jordan C Al Horford A Elliot Williams G Jack Cooley A DETROIT PISTONS Ty Lawson G DeQuan Jones A Jeremy Lamb G Kevin Love A Adonis Thomas G Will Cummings G LOS ANGELES LAKERS Mike Muscala A Jeremy Lin G LeBron James A Brandon Jennings G Arsalan Kazemi A D'Angelo Russell G Mike Scott A Kemba Walker G Nick Minnerath A Jodie Meeks G Chris Walker A Jabari Brown G Paul Millsap A P.J. -

Player.Development .Under

EASTERN ILLINOIS HEAD COACH MIKE MILLER . Eastern.Illinois.University.head.coach.Mike.Miller.has.a.history.of.turning.programs.around.and.as.he.enters. his.seventh.season.at.the.helm.of.the.Panthers.program.he.appears.to.have.the.fortunes.of.the.EIU.program.headed. in.the.right.direction. EIU.has.consistently.ranked.among.the.OVC.leaders.in.player.graduation.and.APR. During. Miller's.tenure.at.EIU.the.program.has.graduated.95.percent.of.its.players. The.Panthers.enter.the.2011-12.season.with.a.roster.that.features.All-OVC.candidates.Jeremy.Granger.and. James.Hollowell.along.with.several.highly.regarded.junior.college.transfers.as.the.Panthers.recruiting.class.was. ranked.in.the.top.75.in.the.nation.by.HoopScoop.com. Granger.ranked.among.the.league's.top.player.makers.last. season.leading.the.team.with.14.5.points.per.game.and.ranking.in.the.top.ten.nationally.in.free.throw.percentage. Hollowell.was.an.All-OVC.Newcomer.selection.two.years.ago.and.last.season.led.EIU.in.rebounding. In 2010 the Panthers posted their first winning season since 2001 with a 19-12 mark as the Panthers won eight straight games to close the season before falling to Murray State in the OVC Tournament semifinals. The 19.wins.by.EIU.marked.the.third.highest.win.total.in.the.Division.I.history.of.the.program.while.eight.straight.wins. during.an.undefeated.February.set.the.school.Division.I.record.for.consecutive.wins.. Tyler Laser was a first team All-OVC selection becoming the first EIU player since 2003 to earn that distinction while.James.Hollowell.was.named.to.the.OVC.All-Newcomer.squad..The.Panthers.entered.the.2010-11.season. -

Sports 1:18:07 Pg 1

FREE PRESS SSSPORTSPORTS Page 8 Colby Free Press Thursday, January 18, 2007 TV LISTINGS sponsored by the COLBY FREE PRESS SATURDAY JANUARY 20 6 AM 6:30 7 AM 7:30 8 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 KLBY/ABC Good Morning Good Morning Good Morning That’s- That’s- Hannah Zack & Emperor Replace- H h Kansas Saturday America (CC) Kansas Saturday Raven Raven Montana Cody New ments KSNK/NBC Today (CC) Paid Paid Babar Dragon 3 2 1 Pen Veggie- Jane- Jacob L j Program Program (EI) (CC) (EI) (CC) Tales Dragon Two Two KBSL/CBS Saturday Early Show (CC) News Cake (EI) Dance Paid Paid 1< NX (CC) Revolut. Program Program K15CG Busi- Market- Mister Thomas- Jay Jay Bob the Signing Dragon- Real For Your Bake Victory d ness Market Rogers Friends the Jet Builder Time! flyTV Moms Home Decorate Garden ESPN SportsCenter (CC) SportsCenter (CC) SportsCenter (CC) SportsCenter (Live) College GameDay College Basketball: O_ (CC) (Live) (CC) Louisville at DePaul. USA Paid Paid Paid Paid Nashville Star (CC) Movie: American Graffiti TTTT (1973) Town teens Movie: P^ Program Program Program Program cruise on graduation night 1962. Richard Dreyfuss. TBS Steve Steve Movie: Blank Check TT (1994, Comedy) Movie: Something to Talk About TTZ Movie: Vegas P_ Harvey Harvey Boy cashes crook’s check for $1 million. (1995, Comedy-Drama) Julia Roberts. (CC) Vacation TZ (1997) WGN Enter- People- Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid HomeTeam Dallas Pa prise People Program Program Program Program Program Program Program Program (CC) TNT (5:00) Movie: Kelly’s Heroes TTT (1970, Movie: Three Kings TTTZ (1999, War) Four Movie: Thirteen Days TTT QW Comedy) Clint Eastwood. -

2019-20 Men's Basketball

GAME 5 vs. Pittsburgh // Monday, November 25, 2019 // Rocket Mortgage by Quicken Loans Fort Myers Tipoff 2019-20 MEN’S BASKETBALL // GAME NOTES 1,600+ ALL-TIME VICTORIES // 31 NCAA TOURNAMENTS // 4 FINAL FOURS [1948, 1951, 1958, 1964] // 21 CONFERENCE TITLES [4-0, 0-0 Big 12] vs. [4-2, 1-0 ACC] n 2019-20 SCHEDULE & RECORD K-STATE PITTSBURGH Monday, November 25 // 5 p.m. CT // Suncoast Credit Union Arena (3,500) // Fort Myers, Fla. Overall Record: 4-0 WILDCATS PANTHERS Big 12: 0-0 n Non-Conference: 4-0 Head Coach: Bruce Weber Head Coach: Jeff Capel III Home: 3-0 n Away: 1-0 n Neutral: 0-0 Record at K-State: 154-89/8th Year Record at Pitt: 18-21/2nd Year MATCHUP OCTOBER Career Record: 467-244/22nd Year Career Record: 180-131/11th Year vs. Pitt: 0-1 (0-1 at neutral site) vs. K-State: 1-4 (0-0 at neutral site) Fri. 25 EMPORIA STATE (Exh.) Big 12 Now W, 86-49 Wed. 30 WASHBURN (Exh.) Big 12 Now W, 66-56 OPENING TIP NOVEMBER u Kansas State (4-0) heads to south for the Rocket Mortgage by Quicken Loans Fort Tues. 5 NORTH DAKOTA STATE Big 12 Now W, 67-54 Myers Tipoff this coming week, as Wildcats begin the semifinal round against ACC Sat. 9 @UNLV ESPN+ W, 60-56 n GAME INFORMATION foe Pittsburgh (4-2) at 5 p.m., CT on Monday, Nov. 25 at the Suncoast Credit Union Wed. 13 MONMOUTH Big 12 Now W, 73-54 Arena in Fort Myers, Fla. -

28Game Notes

GAME 26 2005-06 K-STATE BASKETBALL at NEBRASKA (17-10, 7-7 BIG 12) Wednesday, March 1, 2006 7:07 p.m. CT Devaney Sports Center (13,595) Lincoln, Neb. A TRADITION OF CHAMPIONS | 102 SEASONS, 22 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES, 4 FINAL FOURS, 16 CONFERENCE TITLES KANSAS STATE (14-11, 5-9 Big 12) WILDCATS BEGIN FINAL WEEK OF REGULAR SEASON WITH TRIP TO NEBRASKA ON WEDNESDAY 2005-06 Schedule/Results Kansas State (14-11, 5-9 Big 12) look to close out the final week of the N.3 EA Sports All-Stars (EXH.) W, 62-53 regular season on a strong note, as the Wildcats travel to Lincoln, Neb. to face Nebraska (17-10, 7-7 Big 12) at the Bob Devaney Sports Center on N.10 Emporia State (EXH.) W, 79-75 Wednesday beginning at 7 p.m. After suffering back-to-back one-point N.18 Georgia Southern (WEB) W, 83-58 losses to No. 7 Texas and No. 20 Oklahoma last week, the team will look to N.23 rv/rv New Mexico (FSN) W, 68-56 improve their seeding for next week’s Phillips 66 Big 12 Championship at N.26 Stephen F. Austin (WEB) W, 71-54 the American Airlines Center in Dallas, Texas. Depending on their results THE SERIES... K-State leads 119-90 N.30 Cal State Fullerton (FSN) W, 84-59 this week, the Wildcats can be anywhere from the six-seed to the 12-seed. The teams will be meeting for the 210th time... The D.3 at Washington State (FSN) L, 57-58 The game will be televised throughout Kansas and the Kansas City area Wildcats lead the all-time series, 119-90..