The Character of Ravana and Rama from Buddhist Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramayan Around the World Ravi Kumar [email protected]

Ramayan Around The World Ravi Kumar [email protected] , Contents Acknowledgement.......................................................................................................2 The Timeless Tale .......................................................................................................2 The Universal Relevance of Ramayan .........................................................................2 Ramayan Scriptures in South East Asian Languages....................................................5 Ramayana in the West .................................................................................................6 Ramayan in Islamic Countries .....................................................................................7 Ramayan in Indonesia Islam is our Religion but Ramayan is our Culture..............7 Indonesia Ramayan Presented in Open Air Theatres ................................................9 Ramayan in Malaysia We Rule in the name of Ram’s Paduka.............................10 Ramayan among the Muslims of Philippines..........................................................11 Persian And Arabic Ramayan ................................................................................11 The Borderless Appeal of Ramayan.......................................................................13 Influence of Ramayan in Asian Countries..................................................................16 Influence of Ramayan in Cambodia .......................................................................17 -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present

UGC MRP - COMICS BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present UGC MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT F.NO. 5-131/2014 (HRP) DT.15.08.2015 Principal Investigator: Aneeta Rajendran, Gargi College, University of Delhi UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Acknowledgements This work was made possible due to funding from the UGC in the form of a Major Research Project grant. The Principal Investigator would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Project Fellow, Ms. Shreya Sangai, in drafting this report as well as for her hard work on the Project through its tenure. Opportunities for academic discussion made available by colleagues through formal and informal means have been invaluable both within the college, and in the larger space of the University as well as in the form of conferences, symposia and seminars that have invited, heard and published parts of this work. Warmest gratitude is due to the Principal, and to colleagues in both the teaching and non-teaching staff at Gargi College, for their support throughout the tenure of the project: without their continued help, this work could not have materialized. Finally, much gratitude to Mithuraaj for his sustained support, and to all friends and family members who stepped in to help in so many ways. 1 UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Project Report Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. Scope and Objectives 3 2. Summary of Findings 3 2. Outcomes and Objectives Attained 4 3. -

(Phase-II), Bihar Under RAY 1: Name of Slum:- New Ambedkar Colony

DPR for construction of 1061 DUs at Patna (Phase-II), Bihar under RAY 1: Name of Slum:- New Ambedkar Colony (Sandalpur) Sr.No Name Of Beneficiary Father/Husband's name 1 Manorma Devi Hari Manjhi 2 Manju Devi Bhunesabar Das 3 Mala Devi Hemnt Ram 4 Lalati Devi Mukundas Ravi Das 5 Rajani Devi Sajay Prasad 6 Sumitra Devi Jagdesh Chaudhari 7 Punam Devi Surendra Ram 8 Chonhi Maham Sattan 9 Hema Devi Shiv Ram 10 Sona Devi Raju Chaudhari 11 Sushila Devi Vipin Rout 12 Poonam Devi Rajesh Ram 13 Shyamsundri Devi Kalichran 14 Renu Devi Late Ajay Chaudhari 15 Pinki Devi Bikki Chaudhari 16 Shakuntala Devi Tuntun Ram 17 Rinki Devi Jay Kumar 18 Kiran Devi Santosh Ram 19 Mamta Devi Ashok Das 20 Gunja Devi Prem Ram 21 Anisha Khatoon Late Md Shafique 22 Sangeeta Devi Kundan Ram 23 Chanda Devi Munna Chaudhari 24 Kiran Devi Surendra Rout 25 Amna Khatoon Md. Shamim 26 Babita Devi Sunil Kumar 27 Shila Devi Late Khagri Ram 28 Runi Devi Sanju Manjhi 29 Rina Devi Rajendra Sahani 30 Gulawasa Khatoon Md. Shahid 31 Salma Khatoon Md. Eadu 32 Sapana Devi Ravi Ram 33 Sabina Khatoon Md. Samsulak 34 Sakhandra Devi Late Ramchandra Das 35 Mariyam Khatoon Md. Golden 36 Sunita Devi Ganesh Ram 37 Amna Khatoon Md. Aslam 38 Soni Khatoon Md. Sahid 39 Fula Pati Devi Rambadan Das 40 Sakuntala Devi Ganesh Das 41 Neha Devi Raj Kumar Chaudhary 42 Nitu Devi Dilip Ram 43 Girish Devi Late Swaminath Raut 44 Pinki Devi Ranjit Ram 45 Bina Devi Binay Prasad 46 Mina Devi Ramanand Ram 47 Nilam Devi Suresh Ram 48 Gita Devi Late Santosh Ram 49 Reena Devi Rajesh Ram 50 Jully Devi Sambho Ram 51 Binita Devi Binod Kumar 52 Sumitra Devi Bindeshi Das 53 Laxmi Devi Shukhdeo Das 54 Asha Devi Suresh Ram 55 Radha Kumari Sanjay Kumar 56 Anita Kumari Deepu Kumar 57 Lalmuni Devi Late Raja Ram 58 Tarnnum Khatoon Md. -

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana 1.2 Valmiki Ramayana‘s Importance – In The Words Of Valmiki 1.3 Need for selecting the problem from the point of view of Educational Leadership 1.4 Leadership Lessons from Valmiki Ramayana 1.5 Morality of Leaders in Valmiki Ramayana 1.6 Rationale of the Study 1.7 Statement of the Study 1.8 Objective of the Study 1.9 Explanation of the terms 1.10 Approach and Methodology 1.11 Scheme of Chapterization 1.12 Implications of the study CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION Introduction ―The art of education would never attain clearness in itself without philosophy, there is an interaction between the two and either without the other is incomplete and unserviceable.‖ Fitche. The most sacred of all creations of God in the human life and it has two aspects- one biological and other sociological. If nutrition and reproduction maintain and transmit the biological aspect, the sociological aspect is transmitted by education. Man is primarily distinguishable from the animals because of power of reasoning. Man is endowed with intelligence, remains active, original and energetic. Man lives in accordance with his philosophy of life and his conception of the world. Human life is a priceless gift of God. But we have become sheer materialistic and we live animal life. It is said that man is a rational animal; but our intellect is fully preoccupied in pursuit of materialistic life and worldly pleasures. Our senses and objects of pleasure are also created by God, hence without discarding or condemning them, we have to develop ( Bhav Jeevan) and devotion along with them. -

Shri Sai Baba

Sai Mandir USA 1889 Grand Avenue, Baldwin, NY 11510, USA Designed & Developed by : Praveen Batchu http://www.imagicapps.com SHRI SAI SATCHARITA OR THE WONDERFUL LIFE AND TEACHINGS OF SHRI SAI BABA Adapted from the original Marathi book by Hemadpant by Nagesh Vasudev Gunaji, B.A., L.L.B. 227, Thalakwadi, Belgaum. changes to the current version to make a easy reading experience to American devotees. This book is available for free to all devotees. Published by Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, ‘Sai Niketan’, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. This book will be available for sale at the following places: (1) Court Receiver, Shri Sai Sansthan, Shirdi, P.O. Shirdi, (Dist. Ahmednagar). (2) Shri Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, “Sai Niketan”, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. Copyright reserved by the Sansthan Printed by N.D. Rege, at Mohan Printery, 425-A Mogul Lane, Mahim, Bombay 400 016 and Published by Shri Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, “Sai Niketan”, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. DEDICATION “Whosoever offers to me, with love or devotion, a leaf, a flower, a fruit or water, that offering of love of the pure and self-controlled man is willingly and readily accepted by me.” Lord Shri Krishna in Bhagavad Gita, IX - 26 To Shri Sai Baba The Antaryamin This work with myself Editor : Laura Keller New York, USA SHRI SAI SATCHARITA CONTENTS Preface by the author Preface to the second edition Preface by Shri N.A. -

Engineering Marvels of 1.5 Million Years Old Man Rama Setu Dr

[ VOLUME 2 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEP. 2015 ] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Engineering Marvels of 1.5 Million Years Old Man Rama Setu Dr. M. Sivanandam Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Mahavidyalaya, Kanchipuram- 631 561, Tamil Nadu. Received Aug. 20, 2015 Accepted Sept. 10, 2015 ABSTRACT Rama went on exile for 14 years. At the end of 12th year, near Panchavadi, Sita was abducted by Ravana. Rama with the help of Hanuman located Sita at Ashoka Vatika, Sri Lanka. To reach Sri Lanka, Nala and Vanara sena constructed a sea bridge from Dhanuskhodi, India to Thalaimannar, Sri Lanka with 35 Km length and 3.5 Km width in 5 days with local trees, rocks and gravels. At Sri Lanka Rama killed Ravana and returned with Sita to Ajodhya. The sea bridge with largest area, constructed 1.5 million years before is still considered an engineering marvel. Key words: Rama, Sita, Ravana, Hanuman, Ashoka Vatika, Nala, Rama Setu. 1. Introduction In Tredha Yuga the celestials troubled by They spent 12 years in the forest peacefully demons, especially Ravana, the king of Sri but towards the end of the exile when they Lanka, appealed to Lord Vishnu who agreed moved to Panchavadi near present to take a human incarnation to annihilate Bhadrachalam, Andhra Predesh Sita was Ravana. Rama was born to king Dasharatha of abducted by Ravana by Pushpaga Vimana [3]. Khosala Kingdom [1]. Rama decided to fulfill Figure 1 shows the places of travel during the promise of his father to Kaikeyi, step exile. -

A Case of the Possession Type in India with Evidence of Paranormal Knowledge

Journal o[Scic.icwt~fic.Explorulion. Vol. 3, No. I, pp. 8 1 - 10 1, 1989 0892-33 10189 $3.00+.00 Pergamon Press plc. Printed in the USA. 01989 Society for Scientific Exploration A Case of the Possession Type in India With Evidence of Paranormal Knowledge Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, University of Virginia, Charlottesvill~:VA 22908 Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, India 5epartment of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, Universily of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908 Abstract-A young married woman, Sumitra, in a village of northern India, apparently died and then revived. After a period of confusion she stated that she was one Shiva who had been murdered in another village. She gave enough details to permit verification of her statements, which corresponded to facts in the life of another young married woman called Shiva. Shiva had lived in a place about 100 km away, and she had died violently there-either by suicide or murder-about two months before Sumitra's apparent death and revival. Subsequently, Sumitra recognized 23 persons (in person or in photographs) known to Shiva. She also showed in several respects new behavior that accorded with Shiva's personality and attainments. For example, Shiva's family were Brahmins (high caste), whereas Sumitra's were Thakurs (second caste); after the change in her personality Sumitra showed Brahmin habits that were strange in her fam- ily. Extensive interviews with 53 informants satisfied the investigators that the families concerned had been, as they claimed, completely unknown to each other before the case developed and that Sumitra had had no normal knowledge of the people and events in Shiva's life. -

Seven Sins Referred to in the Ramayana

SEVEN SINS REFERRED TO IN THE RAMAYANA The author of this series of posts Jairam Mohan has a day job where he pores over Excel spreadsheets and Powerpoint presentations. He however believes that his true calling is in writing and as a result his blog http://mahabore.wordpress.com gets regularly updated. Between him and his wife they manage the blog and a naughty two year old daughter. All images used in this document are the courtesy of Google Images search using relevant keywords. No copyrights are owned by the author for these images. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Copyright : Jairam Mohan (http://mahabore.wordpress.com) Kumbhakarna’s sloth Please note that there are various versions of this great epic and therefore my post might contradict with what you have heard or read of this particular incident in the Ramayana. This is only an attempt to map the seven deadly sins to incidents or behavior of particular characters in the Ramayana in a given situation and I have taken liberties with my own interpretations of the same. No offense is meant to any version of this wonderful epic. ============= One version of the story has it that when Ravana, Vibhishana and Kumbhakarna were youngsters, they once prayed to Lord Brahma for his blessings. They were so sure that the Lord would be pleased with their penance and devotion that they had already decided what boon they were going to ask from him. Kumbhakarna was going to ask Lord Brahma for complete dominion over the heavens. Indra, the King of the heavens knew about this wish and he therefore decided to intervene. -

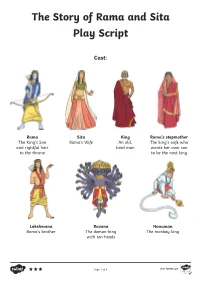

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Sita Ram Baba

सीता राम बाबा Sītā Rāma Bābā סִיטָ ה רְ אַמָ ה בָבָ ה Bābā بَابَا He had a crippled leg and was on crutches. He tried to speak to us in broken English. His name was Sita Ram Baba. He sat there with his begging bowl in hand. Unlike most Sadhus, he had very high self- esteem. His eyes lit up when we bought him some ice-cream, he really enjoyed it. He stayed with us most of that evening. I videotaped the whole scene. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Locations 4961-4964). Trafford. Kindle Edition. … immortal Sita Ram Baba. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Location 5039). Trafford. Kindle Edition. Breaking the Death Habit: The Science of Everlasting Life by Leonard Orr (page 56) ראמה راما Ράμα ראמה راما Ράμα Rama has its origins in the Sanskrit language. It is used largely in Hebrew and Indian. It is derived literally from the word rama which is of the meaning 'pleasing'. http://www.babynamespedia.com/meaning/Rama/f Rama For other uses, see Rama (disambiguation). “Râm” redirects here. It is not to be confused with Ram (disambiguation). Rama (/ˈrɑːmə/;[1] Sanskrit: राम Rāma) is the seventh avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu,[2] and a king of Ayodhya in Hindu scriptures. Rama is also the protagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana, which narrates his supremacy. Rama is one of the many popular figures and deities in Hinduism, specifically Vaishnavism and Vaishnava reli- gious scriptures in South and Southeast Asia.[3] Along with Krishna, Rama is considered to be one of the most important avatars of Vishnu. -

22Sunday-Pg7-0.Qxd (Page 1)

Meet an author who writes very, very short stories books 12 magTHE Mumbai’s scrabble club reveals its secret dna clan 14 ON SUNDAY dMumbai,na August.sunday 23, 2009 body & soul 8 culture station 9 live it up 10 perspective 11 On living with a They capture the The calm of the Window of opportunity transplanted organ other Afghanistan swamp beckons in war on terror 26 TV episodes and Currently, the kids’ One challenge is to 2 animation films entertainment produce the cartoons based on Amar segment is mostly in the signature style Chitra Katha limited to cartoon of Amar Chitra Katha, comics will go on characters from the and not make them air in a few months West and Japan look like Pocahontas IN A BRAND Radhika Raj finds out how the once popular Amar Chitra Katha is getting a new life in the age of animation, where surfing the web and TV channels takes precedence over browsing comics NEW AVATAR COVER STORY www.amarchitrakatha.com and also read e-com- We grew up on a staple ic versions of their favourite tales. ACKpedia, a project in the pipeline, aims to create a free on- diet of Tinkle and stories n the basement of a nondescript building line encyclopedia on the lines of Wikipedia and from Amar Chitra Katha. But in Mahim, artists and animators are pour- Google Knol but “with a sharp focus on every- kids these days have different ing over a sketch. “Hanuman is being very thing Indian and will explore the millions of tastes.