Encroachment Issues in Franchising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Name: Aliaba\Intro

TO MARKET, TO MARKET: ALTERNATIVE METHODS OF DISTRIBUTION IN A WORLD OF E-COMMERCE Prepared for the New York State Bar Association Montreal Seasonal Meeting October 25, 2018 by Andre R. Jaglom* A manufacturer or other supplier seeking to distribute its goods or services internationally has an entire spectrum of distribution options available to it. These options carry varying costs and benefits, offer different advantages and disadvantages, and are regulated in different ways in different countries. Counsel advising a client on choosing among these options must understand the legal distinctions among the alternatives and the legal framework under which they will be regulated, both in the supplier’s home country and in the nations in which it will distribute. E-commerce brings its own challenges, especially where e-commerce sales are made to customers in an area serviced by an otherwise exclusive distributor or agent. Qualified local counsel in foreign jurisdictions thus is essential. Equally important, counsel must understand the client’s business objectives and culture, so as to be able to select options that will best fulfill those objectives and are subject to restrictions that the client can adhere to, thereby minimizing the legal risks associated with meeting the business goals. A. Alternative methods of distribution --- Definitions. 1. Owned outlets Perhaps the simplest approach – but not necessarily the best – to distribution abroad is the do- it-yourself method. A domestic manufacturer can set up shop in another country in which it wishes to market, hire employees, and act as its own importer and distributor in that country, either directly or through a wholly-owned subsidiary. -

Ritters Franchise Info.Pdf

Welcome Ritter’s Frozen Custard is excited about your interest in our brand and joining the most ex- citing frozen custard and burger concept in the world. This brochure will provide you with information that will encourage you to become a Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchisee. Ritter’s is changing the way America eats frozen custard and burgers by offering ultra-pre- mium products. Ritter’s is a highly desirable and unique concept that is rapidly expanding as consumers seek more desirable food options. For the first time, we have positioned ourselves into the burger segment by offering an ultra-premium burger that appeals to the lunch, dinner and late night crowds. If you are an experienced restaurant operator who is looking for the next big opportunity, we would like the opportunity to share more with you about our fran- chise opportunities. The next step in the process is to complete a confidentialNo Obligation application. You will find the application attached with this brochure & it should only take you 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Thank you for your interest in joining the Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchise team! Sincerely, The Ritter’s Team This brochure does not constitute the offer of a franchise. The offer and sale of a franchise can only be made through the delivery and receipt of a Ritter’s Frozen Custard Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD). There are certain states that require the registration of a FDD before the franchisor can advertise or offer the franchise in that state. Ritter’s Frozen Custard may not be registered in all of the registration states and may not offer franchises to residents of those states or to persons wishing to locate a fran- chise in those states. -

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with Asterisks (**) Are Able to Vaccinate 16-17 Year Olds

Posted on May 5, 2021 Sites with asterisks (**) are able to vaccinate 16-17 year olds. Updated at 4:00 PM All sites are able to vaccinate adults 18 and older. Visit www.vaccinefinder.org for a map of vaccine sites near you. Parish Facility Street Address City Website Phone Acadia ** Acadia St. Landry Hospital 810 S Broadway Street Church Point (337) 684-4262 Acadia Church Point Community Pharmacy 731 S Main Street Church Point http://www.communitypharmacyrx.com/ (337) 684-1911 Acadia Thrifty Way Pharmacy of Church Point 209 S Main Street Church Point (337) 684-5401 Acadia ** Dennis G. Walker Family Clinic 421 North Avenue F Crowley http://www.dgwfamilyclinic.com (337) 514-5065 Acadia ** Walgreens #10399 806 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia ** Walmart Pharmacy #310 - Crowley 729 Odd Fellows Road Crowley https://www.walmart.com/covidvaccine Acadia Biers Pharmacy 410 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-3023 Acadia Carmichael's Cashway Pharmacy - Crowley 1002 N Parkerson Avenue Crowley (337) 783-7200 Acadia Crowley Primary Care 1325 Wright Avenue Crowley (337) 783-4043 Acadia Gremillion's Drugstore 401 N Parkerson Crowley https://www.gremillionsdrugstore.com/ (337) 783-5755 Acadia SWLA CHS - Crowley 526 Crowley Rayne Highway Crowley https://www.swlahealth.org/crowley-la (337) 783-5519 Acadia Miller's Family Pharmacy 119 S 5th Street, Suite B Iota (337) 779-2214 Acadia ** Walgreens #09862 1204 The Boulevard Rayne https://www.walgreens.com/covid19vac Acadia Rayne Medicine Shoppe 913 The Boulevard Rayne https://rayne.medicineshoppe.com/contact -

Koios Expands Texas Presence with Upcoming Placements in Select Stores of Drug Emporium, a Pharmacy Chain in TX, AR, LA

Koios Expands Texas Presence with Upcoming Placements in Select Stores of Drug Emporium, a Pharmacy Chain in TX, AR, LA Drug Emporium is a chain of “big box” pharmacies in Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana with standard pharmacy departments as well as “store-within-a-store” features such as “Vitamins Plus”. This month, the Company’s KOIOS™ and Fit Soda™ beverage products will be placed in select Texas locations of Drug Emporium, complementing existing placements of the Company’s products in the state of Texas, including in more than 100 HEB supermarkets. DENVER, CO and VANCOUVER, BC, MARCH 3, 2021 - Koios Beverage Corp. (CSE: KBEV; OTC: KBEVF) (the "Company" or "Koios") is pleased to announce that beginning this month, all five flavours of its KOIOS™ nootropic beverage and all four flavours of its Fit Soda™ functional beverage will carried in select Texas locations of Drug Emporium, a “big box” pharmacy chain with stores in Texas (population 29 million), Arkansas (population 3 million), and Louisiana (population 4.65 million). In late 2020, the Company announced that its Fit Soda™ functional beverage product is now carried in more than 100 HEB supermarkets in Texas. Additionally, the Company announced last week that its KOIOS™ nootropic beverage product was to be added to all locations of Louisiana supermarket chain Matherne’s including its storefront located across from the Louisiana State University’s Tiger Stadium, which is the eighth-largest stadium in the world. The Company has sustained its focus on placing its beverage products with regional grocery chains who can play a key role in accelerating market penetration in a given geographic region. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

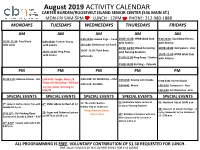

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR CARTER BURDEN/ROOSEVELT ISLAND SENIOR CENTER (546 MAIN ST.) MON-FRI 9AM-5PM LUNCH : 12PM PHONE: 212-980-1888 MONDAYS TUESDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS FRIDAYS AM AM AM AM AM 9:30-10:30: Seated Yoga – Irene 10:00-11:00: NYRR Walk Club 9:30-10:30: Soul Glow Fitness 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 9:30-10:30: Forever Young with Asteria with Keesha with Linda with Zandra 10-11:00: Meditation w/ Rondi 10:30- 12:30: Blood Screening 10:00-12:00: Computers - Alex 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 10:45- 11:45: Ping Pong with Nursing Students 10:45-11:45: NYRR Walk Club with Dexter with Linda 11:00-12:00 Ping Pong – Dexter with ASteria 11:00-12:00 Knitting – Yolanda PM PM PM PM PM 12:30-1:30: Balance Fitness - Sid 1:00-4:00: People, Places, & 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop – John 1:00-4:00: Sewing with Davida 12:00-3:00: Korean Social Things Art Workshop – Michael 1:30-4:45: Scrabble 2:00-4:45: Movie 1:00-3:00: Computers - Alex Summer hiatus returning on 9/03/19 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop -John SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS: SPECIAL EVENTS 01: Medication Safety Lecture at 02: Walmart Trip at 10:00 a.m. 5th: JoAnn’s Fabrics Store Trip with 6th: Elder Abuse Lecture at 11 21: The Carter Burden 11 am w/ Nursing Students Davida 10-2 p.m. Gallery Trip at 11:00 a.m. -

Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Essay Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess Madeline Streiff 1 and Lauren Dundes 2,* 1 Hastings College of the Law, University of California, 200 McAllister St, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-410-857-2534 Academic Editors: Michele Adams and Martin J. Bull Received: 10 September 2016; Accepted: 24 March 2017; Published: 26 March 2017 Abstract: Disney’s animated feature Frozen (2013) received acclaim for presenting a powerful heroine, Elsa, who is independent of men. Elsa’s avoidance of male suitors, however, could be a result of her protective father’s admonition not to “let them in” in order for her to be a “good girl.” In addition, Elsa’s power threatens emasculation of any potential suitor suggesting that power and romance are mutually exclusive. While some might consider a princess’s focus on power to be refreshing, it is significant that the audience does not see a woman attaining a balance between exercising authority and a relationship. Instead, power is a substitute for romance. Furthermore, despite Elsa’s seemingly triumphant liberation celebrated in Let It Go, selfless love rather than independence is the key to others’ approval of her as queen. Regardless of the need for novel female characters, Elsa is just a variation on the archetypal power-hungry female villain whose lust for power replaces lust for any person, and who threatens the patriarchal status quo. The only twist is that she finds redemption through gender-stereotypical compassion. -

The People Shaping the Industry

DRSN041208p81 4/21/08 3:46 PM Page 81 ANNUALANNUAL TheREPORT people shaping the industry --------------------------------2 Chains expand focus amid uncertain economy -------------15 The Drug Store News Power Rx 50---------------------------16 Mass retailers push pharmacy by expanding programs ---17 Regional players strengthen foothold by finding niche-----18 Supermarkets emphasize health/nutrition connection------19 Drug StoreStore News News www.drugstorenews.comwww.drugstorenews.com 08AprilApril 21, 21, 2008 2008• •81 1 DRSN_042108_p83.qxd 4/9/08 8:47 PM Page 83 08 ANNUALREPORT Bill Baxley, Kerr Drug ill Baxley, senior vice Baxley has been with Kerr for crease inventory.” The big- president of merchandis- more than 40 years, beginning gest long-term challenge? B ing and marketing for as a stock clerk in 1967. After “Constantly reinventing Kerr Kerr Drug, said if he weren’t in graduating from pharmacy Drugs,” he said. the drug store industry, he’d be school in 1971, he began work- Baxley said the most sur- of service to humanity, “devel- ing at Kerr’s Store No. 1 in prising development of the oping goals for peace.” Raleigh, N.C. past year occurred outside Those who know Baxley As a retailer, Baxley said with the “collapse of the finan- probably wouldn’t be surprised his top goal this year is to cial markets,” and of Bear by his altruistic leanings. “improve margin and de- Stearns in particular. Paul Beahm, Wal-Mart aul Beahm, senior vice the healthcare arena, where he’s tinue today, but after a major president and general spent the majority -

DRUG EMPORIUM INC (Form: 10-K, Filing Date: 05/31/1996)

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filing Date: 1996-05-31 | Period of Report: 1996-03-02 SEC Accession No. 0000950152-96-002724 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DRUG EMPORIUM INC Mailing Address Business Address 155 HIDDEN RAVINES DR 155 HIDDEN RAVINES DR CIK:832922| IRS No.: 311064888 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0228 POWELL OH 43065 POWELL OH 43065 Type: 10-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 000-16998 | Film No.: 96575732 6145487080 SIC: 5912 Drug stores and proprietary stores Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document 1 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (MARK ONE) [ x ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 [FEE REQUIRED] For the fiscal year ended March 2, 1996 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 [NO FEE REQUIRED] For the transition period from ____________ to ____________ Commission File Number 0-16998 DRUG EMPORIUM, INC. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 31-1064888 (STATE OF INCORPORATION) (IRS EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NO.) ---------- 155 HIDDEN RAVINES DRIVE POWELL, OHIO 43065 (ADDRESS OF PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) (ZIP CODE) ---------- SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: NONE SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: COMMON STOCK, $0.10 PAR VALUE (TITLE OF CLASS) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject so such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Highmark Contracted Pharmacy Vaccination Suppliers As of August 2017 (New Suppliers Are Added Regularly)

Highmark contracted pharmacy vaccination suppliers As of August 2017 (new suppliers are added regularly) Central Pennsylvania Region • Bath Drug • Birdsboro Pharmacy • CVS Pharmacy (multiple locations) • East Berlin Pharmacy • Giant Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Health Depot Pharmacy • Kmart Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Middletown Pharmacy • Minnichs Colonial Pharmacy • Newhard Pharmacy • Palmyra Pharmacy • Rite Aid (multiple locations) • Steelton Pharmacy • The Medicine Shoppe (multiple locations) • Walgreens (multiple locations) • Wegmans Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Weis Pharmacy (multiple locations) Eastern Pennsylvania Region • Amber Pharmacy • CVS Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Giant Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Kmart Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Professional Pharmacy of Pennsburg Inc • Rite Aid (multiple locations) • Walgreens (multiple locations) • Wegmans Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Weis Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Yorke Pharmacy North Eastern Pennsylvania Region • Brundage's Waymart Pharmacy • Cooks Pharmacy • CVS Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Giant Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Harrold's Pharmacy, Inc • Keller & Munro Inc • Kmart Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Mill Hall Pharmacy Inc • Rite Aid Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Sheehan Pharmacy • Walgreens (multiple locations) • Wegmans Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Weis Pharmacy (multiple locations) Page 1 of 2 Western Pennsylvania Region • Alleghany Health Network (AHN) • Martins Pharmacy (multiple locations) • Asti's South Hills Pharmacy • Mill -

Chain Member Companies As of October 15, 2012 Ahold USA

Chain Member Companies as of October 15, 2012 Ahold USA C.R. Pharmacy Service, Inc. dba CarePro Quincy MA Health Services http://www.ahold.com Cedar Rapids IA http://www.careprohealthservices.com Albertsons LLC Boise ID CARE Pharmacies Cooperative, Inc. http://www.albertsonsmarket.com Alexandria VA http://www.carepharmacies.com Alchemist General Inc. Saint Paul MN Coborn's, Incorporated Saint Cloud MN Arrow Prescription Center http://www.cobornsinc.com Hartford CT http://www.arrowrxcenter.com Community Pharmacies, LP/Maine Augusta ME Astrup Drug, Inc. http://www.communityrx.com Austin MN http://www.sterlingdrug.com Concord, Inc. dba Concord Pharmacy Atlanta GA Balls Food Stores (Four B Corp) http://www.concord‐pharmacy.net Kansas City KS http://www.henhouse.com Costco Wholesale dba Costco Pharmacies Issaquah WA The Bartell Drug Company http://www.costco.com Seattle WA http://www.bartelldrugs.com CVS Caremark Corporation Woonsocket RI Bi Lo – Winn Dixie http://www.cvs.com Jacksonville FL http://www.bi‐lo.com Dean Clinic Pharmacy Madison WI Big Y Foods Inc. http://www.deancare.com Springfield MA http://www.bigy.com Dierbergs Pharmacies Chesterfield MO Brookshire Brothers, Inc. http://www.dierbergs.com Lufkin TX http://www.brookshirebrothers.com Discount Drug Mart, Inc. Medina OH Brookshire Grocery Co. http://www.discount‐drugmart.com Tyler TX http://www.brookshires.com Chain Member Companies as of October 15, 2012 Doc's Drugs Ltd. Genoa Healthcare Holdings, LLC Braidwood IL Mercer Island WA http://www.docsdrugs.com http://www.genoahealthcare.com Drug Emporium of West Virginia Giant Eagle, Inc. Charleston WV Pittsburgh PA http://www.drugempwv.com http://www.gianteagle.com Drug World Pharmacies Giant Food Stores, LLC New City NY Carlisle PA http://www.drugworld.com http://www.giantpa.com Eaton Apothecary Gibson Sales, L.P. -

The Enchanted Forest (Disney Frozen 2) Ebook Free Download

THE ENCHANTED FOREST (DISNEY FROZEN 2) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Suzanne Francis | 144 pages | 04 Oct 2019 | Random House Books for Young Readers | 9780593126929 | English | none The Enchanted Forest (Disney Frozen 2) PDF Book Fan Feed 0 The Disney Wiki 1 22 2 Skip to main content. We'll just add that to our archive of you-never-know-what-could-happen Disney theories. Anna's Best Friends Disney Frozen. One of the Enchanted Forest spirits is Gale. But the nice thing about time is that it Who knows. Follow me! Other editions. Perhaps a royal baby on the way? Elsa and Anna's parents are actually alive and may be in Frozen 2 YouTube. Smith, and songwriters Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez — to throw logic out the window, allowing even the direst circumstances to be solved by either a convenient magical power or a song. Facebook Tweet Pin Email. Arendelle's threat in Frozen 2 is linked to Elsa's past YouTube. Visually speaking, if Frozen mostly stood out for its luminous shades of white and blue, Buck and Lee's sequel goes for a wider range of colors befitting its autumnal setting and feel. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. They certainly have some history behind them. Credit: Disney. The Nerdist touted this theory about Frozen 2 , sharing that the "first half of the trailer's devotion to Elsa" featured her "taking on the very beast that took her parents from her so long ago: waves.