THE REINVENTION of the ROUND TABLE Literary Adaptations Throughout the Arthurian Legends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scots Pine Forest

Teacher information 1: The Scots Pine Forest What are native Caledonian pine forests? Native Caledonian pine forest contain Scots pine and a range of other trees, including junipers, birches, willows, and rowan and, in some areas, aspens. Many of the oldest trees in Scotland are found in native pinewoods. As the largest and longest lived tree in the Caledonian forest the Scots pine is a keystone species in the ecosystem, forming the backbone of which many other species depend. Scots pine trees over 200 years old are known as 'grannies', but they are young compared to one veteran pine in a remote part of Glen Loyne that was found to be over 550 years old. Native Caledonian pinewoods are more than just trees. They are home to a wide range of species that are found in similar habitat in Scandinavia and other parts of northern Europe and Russia. Despite this wide distribution, the Scots pine forests in Scotland are unique and distinct from those elsewhere because of the absence of any other native conifers. Native pinewoods have also provided a wide range of products that were used in everyday life in rural Scotland. Timber was used to build houses; berries, fungi and animals living in the pinewood provided food; and fir-candles were cut from the heart of old trees to provide early lighting. More recently, native pinewoods provided timber during the First and Second World Wars when imports to Britain were interrupted. How much native Caledonian pinewood is there in Britain? After the last Ice Age, Scotland’s ‘rainforest’ covered thousands of square kilometres in the Scottish Highlands. -

The Cambridge Songs; a Goliard's Song Book of the 11Th Century

'm )w - - . ¥''•^^1 - \ " .' /' H- l' ^. '' '. H ,' ,1 11 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/cambridgesongsgoOObreuuoft THE CAMBRIDGE SONGS CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, Manager EonDon: FETTER LANE, E.C CFDinburg!): loo PRINCES STREET SriB gotfe : G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Smnbag, Calrutta anB iWalraa: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. arotonto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd. Cokjo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA All rights resenied THE CAMBRIDGE SONGS A GOLIARD'S SONG BOOK OF THE XIth century EDITED FROM THE UNIQUE MANUSCRIPT IN THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BY KARL BREUL Hon. M.A., Litt.D., Ph.D. SCHRODER PROFESSOR OF GERMAN IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Cambridge: -^v \ (I'l at the University Press j^ ^l^ Cambntgc: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS PR nib IN MEMORIAM HENRICI BRADSHAW ET IN HONOREM FRANCISCI JENKINSON HOC OPVSCVLVM DEDICATVM EST PREFACE THE remarkable collection of Medieval Latin poems that is known by the name ' of The Cambridge Songs ' has interested me for more than thirty years. ' My first article Zu den Cambridger Liedern ' was written in the spring of 1885 and published in Volume xxx of Haupt's Zeitschrift filr deutsches Altertkum. The more attention I paid to the songs and the more I corresponded with scholars about some of them, the stronger became my conviction of the importance of having the ten folios of this unique manuscript photographed and of thereby rendering this fascinating collection in its every aspect readily accessible to the students of Medieval literature. It is in truth necessary to invite the co-operation of all such students, whether their subject be Medieval theology, philology, philosophy or music, in the interesting task of elucidating the more difficult poems of what may be regarded as the song book or commonplace book of some early Goliard. -

Nennius' Historia Brittonum

Nennius’ ‘Historia Brittonum’ Translated by Rev. W. Gunn & J. A. Giles For convenience, this text has been assembled and composed into this PDF document by Camelot On-line. Please visit us on-line at: http://www.heroofcamelot.com/ The Historia Brittonum Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................................4 Preface........................................................................................................................................................5 I. THE PROLOGUE..................................................................................................................................6 1.............................................................................................................................................................6 2.............................................................................................................................................................7 II. THE APOLOGY OF NENNIUS...........................................................................................................7 3.............................................................................................................................................................7 III. THE HISTORY ...................................................................................................................................8 4,5..........................................................................................................................................................8 -

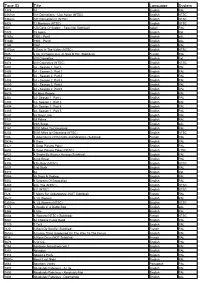

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

STANDARD DATA FORM for Sites Within the ‘UK National Site Network of European Sites’

STANDARD DATA FORM for sites within the ‘UK national site network of European sites’ Special Protection Areas (SPAs) are classified and Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) are designated under: • the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 (as amended) in England and Wales (including the adjacent territorial sea) and to a limited extent in Scotland (reserved matters) and Northern Ireland (excepted matters); • the Conservation (Natural Habitats &c.) Regulations 1994 (as amended) in Scotland; • the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 1995 (as amended) in Northern Ireland; and • the Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 (as amended) in the UK offshore area. Each SAC or SPA (forming part of the UK national site network of European sites) has its own Standard Data Form containing site-specific information. The information provided here generally follows the same documenting format for SACs and SPAs, as set out in the Official Journal of the European Union recording the Commission Implementing Decision of 11 July 2011 (2011/484/EU). Please note that these forms contain a number of codes, all of which are explained either within the data forms themselves or in the end notes. More general information on SPAs and SACs in the UK is available from the SPA homepage and SAC homepage on the JNCC website. These webpages also provide links to Standard Data Forms for all SAC and SPA sites in the UK. https://jncc.gov.uk/ 1 NATURA 2000 - STANDARD DATA FORM For Special Protection Areas (SPA), Proposed Sites for Community Importance (pSCI), Sites of Community Importance (SCI) and for Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) SITE UK9006011 SITENAME Lindisfarne TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Michaela Švachová The Evolution of Merlin: Changing Views in Literature and Film Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím literatury a pramenů uvedených v bibliografii. V Olomouci dne: Podpis: ............................................... Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. for his kind support, guidance and patience. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 6 2 MERLIN IN LITERATURE AND ON THE SCREEN ......................................... 8 2.1 Merlin in High and Late Medieval Chronicles ............................................. 8 2.2 Merlin in Medieval Romance ....................................................................... 9 2.3 Merlin from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries ...................... 11 2.4 Merlin in the Twentieth Century ................................................................ 12 2.5 Merlin on the Screen................................................................................... 14 3 GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH ........................................................................... 16 3.1 The Origin of Merlin and His Name .......................................................... 17 3.2 Merlin in The History of the Kings of Britain............................................ -

Forest Research Annual Report and Accounts 2007-2008

Annual Report and Accounts 2007–2008 The Research Agency HC 717 of the Forestry Commission Forest Research Annual Report and Accounts 2007–2008 Together with the Comptroller and Auditor General’s Report on the Accounts Presented to Parliament in pursuance of Section 45 of the Forestry Act 1967 and Section 5 of the Exchequer and Audit Departments Act 1921 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 17 July 2008 Edinburgh: The Stationery Office HC 717 £18.55 The Research Agency of the Forestry Commission Annual Report and Accounts 2007–2008 Forest Research | 1 Enquiries relating to this publication should be addressed to: Forest Research Alice Holt Lodge Farnham Surrey GU10 4LH T: 01420 22255 E: [email protected] Contact this address if you would like to request this document in large print or other format and for information on language translations. © Crown Copyright 2008 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978 010295211 7 2 | Forest Research Annual Report and Accounts 2007–2008 Contents Chief Executive’s Introduction . -

Emma of Normandy, Urraca of León-Castile and Teresa of Portugal

Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras The power of the Genitrix - Gender, legitimacy and lineage: Emma of Normandy, Urraca of León-Castile and Teresa of Portugal Ana de Fátima Durão Correia Tese orientada pela Profª Doutora Ana Maria S.A. Rodrigues, especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em História do Género 2015 Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………. 3-4 Resumo............................................................................................................... 5 Abstract............................................................................................................. 6 Abbreviations......................................................................................................7 Introduction………………………………………………………………..….. 8-20 Chapter 1: Three queens, three lives.................................................................21 -44 1.1-Emma of Normandy………………………………………………....... 21-33 1-2-Urraca of León-Castile......................................................................... 34-39 1.3-Teresa of Portugal................................................................................. 39- 44 Chapter 2: Queen – the multiplicity of a title…………………………....… 45 – 88 2.1 – Emma, “the Lady”........................................................................... 47 – 67 2.2 – Urraca, regina and imperatrix.......................................................... 68 – 81 2.3 – Teresa of Portugal and her path until regina..................................... 81 – 88 Chapter 3: Image -

The Story of Abernethy National Nature Reserve

Scotland’s National Nature Reserves For more information about Abernethy - Dell Woods National Nature Reserve please contact: East Highland Reserves Manager, Scottish Natural Heritage, Achantoul, Aviemore, Inverness-shire, PH22 1QD Tel: 01479 810477 Fax: 01479 811363 Email: [email protected] The Story of Abernethy- Dell Woods National Nature Reserve The Story of Abernethy - Dell Woods National Nature Reserve Foreword Abernethy National Nature Reserve (NNR) lies on the southern fringes of the village of Nethybridge, in the Cairngorms National Park. It covers most of Abernethy Forest, a remnant of an ancient Scots pine forest that once covered much of the Scottish Highlands and extends high into the Cairngorm Mountains. The pines we see here today are the descendants of the first pines to arrive in the area 8,800 years ago, after the last ice age. These forests are ideal habitat for a vast number of plant and animal species, some of which only live within Scotland and rely upon the Caledonian forests for their survival. The forest of Abernethy NNR is home to some of the most charismatic mammals and birds of Scotland including pine marten, red squirrel, capercaillie, osprey, Scottish crossbill and crested tit. It is also host to an array of flowers characteristic of native pinewoods, including twinflower, intermediate wintergreen and creeping lady’s tresses. Scotland’s NNRs are special places for nature, where many of the best examples of Scotland’s wildlife are protected. Whilst nature always comes first on NNRs, they also offer special opportunities for people to enjoy and find out about the richness of our natural heritage. -

The Caledonian Forest!

Native Forest in the Highlands ! - the Caledonian Forest! Alan Watson Featherstone" Executive Director, Trees for Life" Forestry in the Highlands Conference What is (or was) the Caledonian Forest?! Forestry in the Highlands Conference What is (or was) the Caledonian Forest?! A massive expanse of dense pinewood…? Forestry in the Highlands Conference What is (or was) the Caledonian Forest?! …of which only a few scattered derelict remnants survive? Forestry in the Highlands Conference Changing perspectives on the forest! "A variety of woodland types within * the forest – not just pines "" " "Greater component of broadleaved * trees" " * "Varied age structure" " * "The forest is a whole community, of fungi, plants, insects, birds & animals" "" * "The forest is dynamic, changing over time, and from area to area" Forestry in the Highlands Conference A range of woodland types in the forest! The Atlantic oakwoods, such as this in Ariundle Away from the west coast, narrow gorges with NNR, are a bryophyte-rich temperate rainforest cascading rivers, such as this is Glen Moriston, component of the Caledonian Forest! create similar a rainforest micro-climate! Forestry in the Highlands Conference Riparian and floodplain woodlands! Alder and birches in riparian woodland along Alder trees in the floodplain of the! a burn in Glen Affric! River Moriston! Forestry in the Highlands Conference Treeline and montane scrub communities! Krummholz pines and juniper at ! Reindeer lichen, juniper & birches at 500 Creag Fiaclach in the Cairngorms! metres on an island on the Hilton Estate! Forestry in the Highlands Conference Bog woodland and clearings in the forest! This natural clearing in the forest at Dundreggan is formed by an area of boggy ground, which is the habitat for the strawberry spider (Araneus alsine)! Stunted pine in an area of bog woodland ! in Glen Affric! Forestry in the Highlands Conference Diversity of tree species in the Forest! Oak and hazel growing amongst pine and birch Aspens in autumn in Glen Affric. -

Does the Conservation Status of a Caledonian Forest Also Indicate Cultural Ecosystem Value?

Does the conservation status of a Caledonian forest also indicate cultural ecosystem value? David Edwards, Tim Collins and Reiko Goto Abstract The Black Wood of Rannoch is one of the largest remnants of ancient, semi-natural Caledonian pine forest in Scotland. It is culturally important as a location for aesthetic and spiritual experience, artistic inspiration, (bio)cultural heritage and a sense of identity and belonging by local communities and urban visitors. Despite this, the values that inform its management are almost exclusively those associated with biodiversity conservation. This focus has proved very effective in protecting the forest from destructive economic interests. However, it could have two negative effects. Firstly, it could continue to downplay the significance given to the full range of cultural benefits, and constrain their recognition and expression to those that are realised by a policy of conservation. Secondly, it could be used as a ‘precautionary principle’ to justify exclusion of visitors. This paper reports on a series of workshops, discussions, events and residencies, led by two environmental artists, to prompt a debate that rethinks existing narratives of the value and management of the Black Wood and the Caledonian forest more broadly. We analyse the range of cultural ecosystem services associated with the forest, and discuss how these might be realised through six alternative management scenarios. In conclusion we suggest that the new concept of biocultural diversity offers a unifying principle with which to guide a new vision of social and ecological restoration. 1. Introduction At around 1000 hectares in size, the Black Wood of Rannoch in Highland Perthshire is one of the largest remnants of the ancient Caledonian pine forests that once extended across much of Scotland after the last glaciation. -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L.