Importing the American Liberal Arts College?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

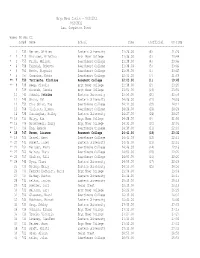

Bryn Mawr Invite - 9/2/2011 9/2/2011 Last Completed Event

Bryn Mawr Invite - 9/2/2011 9/2/2011 Last Completed Event Women 5k Run CC Comp# Name School Time UnOfficial UO TIME =================================================================================================================== 1 732 Kerner, Whitney Eastern University 21:26.00 {8} 21:26 * 2 710 Kronauer, Kristina Bryn Mawr College 21:36.00 {3} 20:44 * 3 755 Frick, Melissa Swarthmore College 21:38.00 {4} 20:46 * 4 758 Hammond, Rebecca Swarthmore College 21:38.03 {5} 20:46 * 5 751 Beebe, Stepanie Swarthmore College 21:39.00 {6} 20:47 * 6 757 Gonzalez, Katie Swarthmore College 22:01.00 {7} 21:09 ** 7 750 Torriente, Klarisse Rosemont College 22:03.00 {1} 19:45 ** 8 708 Keep, Claudia Bryn Mawr College 22:38.00 {2} 20:20 9 709 Kosarek, Cassie Bryn Mawr College 23:51.00 {19} 23:51 10 743 Schmid, K atrina Eastern University 23:59.00 {20} 23:59 11 745 Wrona, Val Eastern University 24:06.00 {21} 24:06 12 752 Cina-Sklar, Zoe Swarthmore College 24:11.00 {22} 24:11 13 768 Violante, Ximena Swarthmore College 24:24.00 {23} 24:24 14 728 Cunningham, Hailey Eastern University 24:27.00 {24} 24:27 ** 15 716 Wiley, Kim Bryn Mawr College 24:28.00 {9} 21:59 ** 16 704 Brownawell, Emily Bryn Mawr College 24:35.00 {10} 22:06 ** 17 754 Eng, Amanda Swarthmore College 24:39.00 {11} 22:10 * 18 747 Brown, Lisanne Rosemont College 24:41.00 {18} 23:32 ** 19 766 Saarel, Emma Swarthmore College 24:41.03 {12} 22:11 ** 20 741 Rupert, Josey Eastern University 24:46.00 {13} 22:16 ** 21 761 Marquez, Mayra Swarthmore College 24:46.03 {14} 22:16 ** 22 763 Naiman, Thera Swarthmore -

The Ursinus Weekly, February 15, 1967

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Ursinus Weekly Newspaper Newspapers 2-15-1967 The rsinU us Weekly, February 15, 1967 Lawrence Romane Ursinus College Herbert C. Smith Ursinus College Mort Kersey Ursinus College Frederick Jacob Ursinus College Lewis Bostic Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly Part of the Cultural History Commons, Higher Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Romane, Lawrence; Smith, Herbert C.; Kersey, Mort; Jacob, Frederick; and Bostic, Lewis, "The rU sinus Weekly, February 15, 1967" (1967). Ursinus Weekly Newspaper. 196. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly/196 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ursinus Weekly Newspaper by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .... rstnus Volume LXVI WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 1967 Number 6 Lorelei, t he Drifters, and Winter I. F. Highlight February Social Events Winter Weekend Approaches Rock and Roll Comes to Ursinus Tomorrow evening at 8 :00 the third annual l.F.-I.s. Win On Thursday, February 16, the Agency will present the ter \Veekend will again dismember the myth of Ursinus as a DRIFTERS in concert at Ursinus. A group well known a suitcase college. In cooperation with the Agency this year mong those who enjoy rock and roll, the Drifters have been the Inter-Fraternity Inter-Sorority Council is beginning their one of America's most popular vocal groups since 1955. -

********W********************************* Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Bestthat Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 343 881 SP 033 682 AUTHOR Warren, Thomas, Ed. TITLE A View from the Top: Liberal Arts Presidentson Teacher Education. INSTITUTION Association of Independent Liberal ArtsColleges for Teacher Education. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8191-7981-7 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 177p. AVAILABLE FROM University Press of America, Inc., 4720 Boston Way, Lanham, MD 20706. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Faculty; *College Presidents;*College Role; Elementary Secondary Education; Excellence in Education; Futures (of Society); Higher Education; *Institutional Mission; *Liberal Arts; Private Colleges; *Teacher Education Programs; *Teaching (Occupation) IDENTIFIERS Professionalism; Reform Efforts ABSTRACT This monograph presents articles written bycollege presidents about teacher education in liberalarts settings. The publication is organized into 16 chapters (alphabeticalby institution) as follows: "LiberalArts College: The Right Crucibles for Teacher Education" (John T. Dahlquist,Arkansas College); "Teacher Education: Liberal Arts Colleges'Unique Contribution" (Thomas Tredway, Augustana College);"Presidential Involvement in Teacher Education" (Harry E. Smith, Austin College);"Dollars and Sense in Educating Teachers" (Roger H. Hul).,Beloit College/Union College); "Restoring the Balance" (Paulj. Dovre, Concordia College); "Small Is Beautiful: Teacher Education inthe Liberal Arts Setting" Oactor E. Stoltzfus, Goshen College);"Participatory Management: A Success Story" (Bill Williams, Grand Canyon -

Why a Women's College?

Why a Women’s College? By Collegewise counselors (and proud women’s college graduates): Sara Kratzok and Casey Near Copyright © 2016 by Collegewise This edition is designed to be viewed on screen to save trees and to be emailed to fellow students, parents, and counselors. You are given the unlimited right to distribute this guide electronically (via email, your website, or any other means). You can print out pages and put them in your office for your students. You can include the link in a newsletter, send it to parents in your school community, hand it out at an event for students or parents, and generally share it with anyone who is interested. But you may not alter this guide in any way, or charge for it, without written permission from Collegewise. Fifth Edition February 2016 www.collegewise.com A note from the authors In the time since we wrote this guide, women's colleges have been in the news a lot. So, we thought we’d review the latest updates in the world of women’s colleges with some tips on how to consider this news in your college search. The content of the guide hasn’t changed, but we hope this update will help you see women’s colleges in a new light. In March 2013, news broke that Sweet Briar College would be abruptly closing its doors at the end of the academic year. This wasn't the first, nor the only, women's college to close since we wrote this guide, but it captured the media's (and higher education's) attention. -

College/University Visit Clusters

COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY VISIT CLUSTERS The groupings of colleges and universities below are by no means exhaustive; these ideas are meant to serve as good starting points when beginning a college search. Happy travels! BOSTON/RHODE ISLAND AREA Large: Boston University University of Massachusetts at Boston Northeastern University Medium: Bentley University (business focus) Boston College Brandeis University Brown University Bryant College (business focus) Harvard University Massachusetts Institute of Technology Providence College University of Massachusetts at Lowell University of Rhode Island Suffolk University Small: Babson College (business focus) Emerson College Olin College Rhode Island School of Design (art school) Salve Regina University Simmons College (all women) Tufts University Wellesley College (all women) Wheaton College CENTRAL/WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS Large: University of Massachusetts at Amherst/Lowell Medium: College of the Holy Cross Worcester Polytechnic Institute Small: Amherst College Clark University Hampshire College Mount Holyoke College (all women) Smith College (all women) Westfield State University Williams College CONNECTICUT Large: University of Connecticut Medium: Fairfield University Quinnipiac University Yale University Small: Connecticut College Trinity College Wesleyan University NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND Large: University of New Hampshire University of Vermont Medium: Dartmouth College Middlebury College Small: Bates College Bennington College Bowdoin College Colby College College of the Atlantic Saint Anselm College -

Historical Memory Symposium | June 2-5, 2019 Gettysburg College

! Historical Memory Symposium | June 2-5, 2019 Gettysburg College | Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, USA Sunday, June 2nd 6 pm Welcome dinner at the Gettysburg Hotel Monday, June 3rd 9 am Opening Remarks & Introductions | All seminars held in Science Center 200 9:30-10:30 am Monumental Commemorations Julian Bonder, architect; Roger Williams College Exploring the role of monuments, parks and museums in preserving and celebrating historic events and in shaping collective memory 11 am-3 pm Guided Visit to Gettysburg Battlefield Led by Peter Carmichael and Jill Titus, Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College 3 pm-5:30 pm Gettysburg Museum and Visitors’ Center Tuesday, June 4th 9-10:15 am Memory vis-à-vis Recent Events in the United States and Central America Stephen Kinzer, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University Location: Science Center 200 10:30-11:45 am Historical Memory Research I: SPAIN Brief presentations by faculty and students about their research focused on historical and collective memory, with a focus on methodologies. Juanjo Romero, Resident Director, CASA Barcelona Ava Rosenberg, Returning student, CASA Spain Maria Luisa Guardiola, Professor, Swarthmore 12-1 pm Lunch 1:15-2:15 pm Historical Memory Research II: CUBA Brief presentations by faculty and students about their research focused on historical and collective memory, with a focus on methodologies. Somi Jun, Returning student, CASA Cuba Rainer Schultz, Resident Director, CASA Cuba 2:30-4 pm De-Brief and Sharing Project Ideas 5:30-7:30 pm Dinner and closing remarks | Atrium Dining Hall Speaker Bios Julian Bonder Professor of Architecture, Roger Williams University Julian Bonder is a teacher, designer and architect born in New York and raised in Argentina. -

Elite Colleges Or Colleges for the Elite?: a Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege Margaret Lee O'brien Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Honors Theses By Year Student Honors Theses 5-22-2011 Elite Colleges or Colleges For the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege Margaret Lee O'Brien Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_honors Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Margaret Lee, "Elite Colleges or Colleges For the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege" (2011). Dickinson College Honors Theses. Paper 129. This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elite Colleges or Colleges for the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege By Margaret O'Brien Submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors Requirements For the Dickinson College Department of Sociology Professor Steinbugler, Advisor Professor Schubert, Reader Professor Love, Reader 16 May 2011 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ~----------------------~2 2. Literature Review 4 3. Methodology 20 4. Data Analysis 29 5. Conclusion 48 6. Acknowledgements 52 7. Appendix A (Interview Recruitment Flier) 53 8. Appendix B (Interview Recruitment Email) 54 9. References 55 1 Studying privileged people is important because they create the ladders that others must climb to move up in the world. Nowhere is this more true than in schools, which have been official ladders of mobility and opportunity in U.S. society for hundreds of years. Mitchell L. Stevens, Creating a Class The college experience is often portrayed as a carefree four years filled with new experiences, lifelong friendships, parties, papers and the ease of a semi-sheltered, yet independent, life. -

The Classicists of Ohio Wesleyan University: 1844-2014 © Donald Lateiner 2014

The Classicists of Ohio Wesleyan University: 1844-2014 © Donald Lateiner 2014 When Ohio Wesleyan could hire only four professors to teach in Elliott Hall (and there was yet no other building), one of the four professors taught Latin and another taught Ancient Greek. This I was told in 1979, when I arrived at Sturges Hall to teach the Classics. True or not,1 the story reflects the place of Greek and Latin in the curriculum of the mid-1800s. Our first graduate, William Godman, followed the brutally demanding “classical course.” The percentage of faculty teaching Greek and Latin steadily declined in the Nineteenth and most of the Twentieth century. New subjects and new demands attracted Wesleyan students. Currently we descry another Renaissance of antiquity at Ohio Wesleyan in Classical Studies. Sturges Hall itself was opened in 1855, its original function, as you see in the photo on the left, to serve the campus as library with alcoves divided by subject. Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams studied and revered Greek and Roman writers, their demanding languages, and their culture. Ben Franklin was not interested. For many decades, mere admission to Harvard College required a solid knowledge of Greek and Latin. One of Ohio’s sons who became President of the United States, James A. Garfield, was both a student and a teacher of Greek and Latin. Legend holds that he could write Greek with one hand, Latin with the other--at the same time. I doubt it, but Thucydides tells us humans usually doubt that others can achieve what they know they cannot. -

Liberal Arts Colleges During the Great Recession

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Liberal Arts Colleges During the Great Recession: Examining Organizational Adaptation and Institutional Change Ashlie Junot Hilbun University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Hilbun, Ashlie Junot, "Liberal Arts Colleges During the Great Recession: Examining Organizational Adaptation and Institutional Change" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 798. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/798 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGES DURING THE GREAT RECESSION: EXAMINING ORGANIZATIONAL ADAPTATION AND INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGES DURING THE GREAT RECESSION: EXAMINING ORGANIZATIONAL ADAPTATION AND INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Higher Education By Ashlie Junot Hilbun Centenary College of Louisiana Bachelor of Arts in Psychology, 2006 Tulane University Master of Social Work, 2007 May 2013 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Liberal arts colleges strived to adapt to environmental shifts at the turn of the twenty-first century and remain relevant -

Library Chairman Issues Statement

ntun {flefokeburrj - tttlmington 26TH YEAR • NO. 4 ■COPVRIGHT 1981 WllMINGION NEWS CO. INC WILMINGTON. MASS.. JANUARY 28, 1981 AIL RIGHTS RESERVED PUB NO. 635 340 6582346 32 PAGES Where will the Special mass at St. Thomas Library chairman A Mass of Thanksgiving for the celebrated on Thursday evening at axe fall first? release of the hostages will be soven o'clock at St. Thomas of Yillanova Church. issues statement Will Wilmington's ambulance Among the areas mentioned by Morris as vulnerable were rubbish service be cut because of Proposition The following statement was January 2. 1981, I received a memo 2'*? removal, library, recreation, am- In a dicsussion of possible cuts. bulance services, police specialties, submitted to the Town Crier by John from the town manager requesting family counseling, and possibly street McNaughton. chairman of the additional budget information. The Wilmington Town Manager Sterling memo reached me December 24. Morris Monday night told the lights. Wilmington Board of Library Morris said that probably 35 Trustees. Because of the holidays and other selectmen that he found the am- personal matters it was not possible bulance service "extremely positions would be eliminated, and Recent newspaper articles con- possibly another 15, just to pay for the to call an immediate meeting. On vulnerable." cerning the Wilmington Library are December 31, 1980, I telephoned the Morris said that the ambulance by unemployment costs. unfortunate and misleading. Finance Committee Chairman '—K board clerk and asked her to set up a state law must be manned by EMT's '. The role of the Board of Library meeting for Friday, January 2,1981 at (Emergency Medical Technicians) Walter Kaminski noted that the Trustees is to establish policy and discussion was "purely speculative. -

Science at Liberal Arts Colleges: a Better Education?

Thomas R. Cech Science at Liberal Arts Colleges 195 Science at Liberal Arts Colleges: A Better Education? T WAS THE SUMMER OF 1970. Carol and I had spent four years at Grinnell College, located in the somnolent farming com I munity of Grinnell, Iowa. Now, newly married, we drove westward, where we would enter the graduate program in chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. How would our liberal arts education serve us in the Ph.D. program of one of the world’s great research universities? As we met our new classmates, one of our preconceptions quickly dissipated: Ber keley graduate students were not only university graduates. They also hailed from a diverse collection of colleges—many of them less known than Grinnell. And as we took our qualifying examinations and struggled with quantum mechanics problem sets, any residual apprehension about the quality of our under graduate training evaporated. Through some combination of what our professors had taught us and our own hard work, we were well prepared for science at the research university level. I have used this personal anecdote to draw the reader’s interest, but not only to that end; it is also a “truth in advertis ing” disclaimer. I am a confessed enthusiast and supporter of the small, selective liberal arts colleges. My pulse quickens when I see students from Carleton, Haverford, and Williams who have applied to our Ph.D. program. I serve on the board of trustees of Grinnell College. On the other hand, I teach undergraduates both in the classroom and in my research labo ratory at the University of Colorado, so I also have personal experience with science education at a research university.