The Problem of Constitutional Law Reform in New Zealand: a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

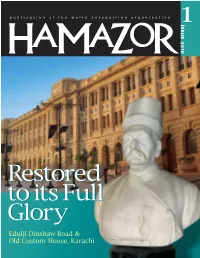

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Wai L Rev 2017-1 Internals.Indd

Waikato Law Review TAUMAURI VOLUME 25, 2017 A Commentary on the Supreme Court Decision of Proprietors of Wakatū v Attorney-General 1 Karen Feint The Native Land Court at Cambridge, Māori Land Alienation and the Private Sector 26 RP Boast More than a Mere Shadow? The Colonial Agenda of Recent Treaty Settlements 41 Mick Strack and David Goodwin Section 339 of the Property Law Act 2007: A Tragedy of the Commonly Owned? 59 Thomas Gibbons Trimming the Fringe: Should New Zealand Limit the Cost of Borrowing in Consumer Credit Contracts? 79 Sascha Mueller Takiri ko te Ata Symposium Matiu Dickson: The Measure of the Man 100 Ani Mikaere Mā Wai Rā te Marae e Taurima? The Importance of Leadership in Tauranga Moana 107 Charlie Rahiri Book Review: International Indigenous Rights in Aotearoa New Zealand 111 Seanna Howard Book Review: He Reo Wāhine: Māori Women’s Voices from the Nineteenth Century 115 Linda Te Aho Editor in Chief Linda Te Aho Editorial Assistance Mary-Rose Russell, Carey Church Senior Student Editor Philip McHugh Student Editors Nicole Morrall, Aref Shams, Cassidy McLean-House EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Chief Justice, The Honourable Dame Sian Elias (honorary member), Chief Justice of New Zealand. Professor John Borrows, JD (Toronto), PhD (Osgoode Hall), LL.D (Dalhousie), FRSC, Professor, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law, Nexen Chair in Indigenous Leadership, University of Victoria, (Canada). Associate Professor T Brettel Dawson, Department of Law, Carleton University, Academic Director, National Judicial Institute (Canada). Gerald Bailey, QSO, LLB (Cant), Hon D (Waikato), Consultant Evans Bailey, Lawyers, former Chancellor of University of Waikato and member of the Council of Legal Education. -

Columbia Law Review

COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 99 DECEMBER 1999 NO. 8 GLOBALISM AND THE CONSTITUTION: TREATIES, NON-SELF-EXECUTION, AND THE ORIGINAL UNDERSTANDING John C. Yoo* As the globalization of society and the economy accelerates, treaties will come to assume a significant role in the regulation of domestic affairs. This Article considers whether the Constitution, as originally understood, permits treaties to directly regulate the conduct of private parties without legislative implementation. It examines the relationship between the treaty power and the legislative power during the colonial, revolutionary, Framing, and early nationalperiods to reconstruct the Framers' understandings. It concludes that the Framers believed that treaties could not exercise domestic legislative power without the consent of Congress, because of the Constitution'screation of a nationallegislature that could independently execute treaty obligations. The Framers also anticipatedthat Congress's control over treaty implementa- tion through legislation would constitute an importantcheck on the executive branch'spower in foreign affairs. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................... 1956 I. Treaties, Non-Self-Execution, and the Internationalist View ..................................................... 1962 A. The Constitutional Text ................................ 1962 B. Globalization and the PoliticalBranches: Non-Self- Execution ............................................. 1967 C. Self-Execution: The InternationalistView ................ -

From Privy Council to Supreme Court: a Rite of Passage for New Zealand’S Legal System

THE HARKNESS HENRY LECTURE FROM PRIVY COUNCIL TO SUPREME COURT: A RITE OF PASSAGE FOR NEW ZEALAND’S LEGAL SYSTEM BY PROFESSOR MARGARET WILSON* I. INTRODUCTION May I first thank Harkness Henry for the invitation to deliver the 2010 Lecture. It gives me an opportunity to pay a special tribute to the firm for their support for the Waikato Law Faculty that has endured over the 20 years life of the Faculty. The relationship between academia and the profession is a special and important one. It is essential to the delivery of quality legal services to our community but also to the maintenance of the rule of law. Harkness Henry has also employed many of the fine Waikato law graduates who continue to practice their legal skills and provide leadership in the profession, including the Hamilton Women Lawyers Association that hosted a very enjoyable dinner in July. I have decided this evening to talk about my experience as Attorney General in the establish- ment of New Zealand’s new Supreme Court, which is now in its fifth year. In New Zealand, the Attorney General is a Member of the Cabinet and advises the Cabinet on legal matters. The Solici- tor General, who is the head of the Crown Law Office and chief legal official, is responsible for advising the Attorney General. It is in matters of what I would term legal policy that the Attorney General’s advice is normally sought although Cabinet also requires legal opinions from time to time. The other important role of the Attorney General is to advise the Governor General on the appointment of judges in all jurisdictions except the Mäori Land Court, where the appointment is made by the Minister of Mäori Affairs in consultation with the Attorney General. -

The 2008 Election: Reviewing Seat Allocations Without the Māori Electorate Seats June 2010

working paper The 2008 Election: Reviewing seat allocations without the Māori electorate seats June 2010 Sustainable Future Institute Working Paper 2010/04 Authors Wendy McGuinness and Nicola Bradshaw Prepared by The Sustainable Future Institute, as part of Project 2058 Working paper to support Report 8, Effective M āori Representation in Parliament : Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy Disclaimer The Sustainable Future Institute has used reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes and the Institute is not liable for the content of such website or other source. Published Copyright © Sustainable Future Institute Limited, June 2010 ISBN 978-1-877473-56-2 (PDF) About the Authors Wendy McGuinness is the founder and chief executive of the Sustainable Future Institute. Originally from the King Country, Wendy completed her secondary schooling at Hamilton Girls’ High School and Edgewater College. She then went on to study at Manukau Technical Institute (gaining an NZCC), Auckland University (BCom) and Otago University (MBA), as well as completing additional environmental papers at Massey University. As a Fellow Chartered Accountant (FCA) specialising in risk management, Wendy has worked in both the public and private sectors. -

Translating the Constitution Act, 1867

TRANSLATING THE CONSTITUTION ACT, 1867 A Legal-Historical Perspective by HUGO YVON DENIS CHOQUETTE A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Law in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2009 Copyright © Hugo Yvon Denis Choquette, 2009 Abstract Twenty-seven years after the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Constitution of Canada is still not officially bilingual in its entirety. A new translation of the unilingual Eng- lish texts was presented to the federal government by the Minister of Justice nearly twenty years ago, in 1990. These new French versions are the fruits of the labour of the French Constitutional Drafting Committee, which had been entrusted by the Minister with the translation of the texts listed in the Schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982 which are official in English only. These versions were never formally adopted. Among these new translations is that of the founding text of the Canadian federation, the Constitution Act, 1867. A look at this translation shows that the Committee chose to de- part from the textual tradition represented by the previous French versions of this text. In- deed, the Committee largely privileged the drafting of a text with a modern, clear, and con- cise style over faithfulness to the previous translations or even to the source text. This translation choice has important consequences. The text produced by the Commit- tee is open to two criticisms which a greater respect for the prior versions could have avoided. First, the new French text cannot claim the historical legitimacy of the English text, given their all-too-dissimilar origins. -

What the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act Aimed to Do, Why It Did Not Succeed and How It Can Be Repaired

169 WHAT THE NEW ZEALAND BILL OF RIGHTS ACT AIMED TO DO, WHY IT DID NOT SUCCEED AND HOW IT CAN BE REPAIRED Sir Geoffrey Palmer* This article, by the person who was the Minister responsible for the introduction and passage of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, reviews 25 years of experience New Zealand has had with the legislation. The NZ Bill of Rights Act does not constitute higher law or occupy any preferred position over any other statute. As the article discusses, the status of the NZ Bill of Rights Act has meant that while the Bill of Rights has had positive achievements, it has not resulted in the transformational change that propelled the initial proposal for an entrenched, supreme law bill of rights in the 1980s. In the context of an evolving New Zealand society that is becoming ever more diverse, more reliable anchors are needed to ensure that human rights are protected, the article argues. The article discusses the occasions upon which the NZ Bill of Rights has been overridden and the recent case where for the first time a declaration of inconsistency was made by the High Court in relation to a prisoner’s voting rights. In particular, a softening of the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, as it applies in the particular conditions of New Zealand’s small unicameral legislature, is called for. There is no adequate justification for maintaining the unrealistic legal fiction that no limits can be placed on the manner in which the New Zealand Parliament exercises its legislative power. -

Canada's Evolving Crown: from a British Crown to A

Canada’s Evolving Crown 108 DOI: 10.1515/abcsj-2014-0030 Canada’s Evolving Crown: From a British Crown to a “Crown of Maples” SCOTT NICHOLAS ROMANIUK University of Trento and JOSHUA K. WASYLCIW University of Calgary Abstract This article examines how instruments have changed the Crown of Canada from 1867 through to the present, how this change has been effected, and the extent to which the Canadian Crown is distinct from the British Crown. The main part of this article focuses on the manner in which law, politics, and policy (both Canadian and non-Canadian) have evolved a British Imperial institution since the process by which the federal Dominion of Canada was formed nearly 150 years ago through to a nation uniquely Canadian as it exists today. The evolution of the Canadian Crown has taken place through approximately fifteen discrete events since the time of Canadian confederation on July 1, 1867. These fifteen events are loosely categorized into three discrete periods: The Imperial Crown (1867-1930), A Shared Crown (1931-1981), and The Canadian Crown (1982-present). Keywords: Imperial, the London Conference, the Nickle Resolution, the British North America Act, Queen Victoria, Sovereignty, the Statute of Westminster 109 Canada’s Evolving Crown Introduction Of Canadian legal and governmental institutions, the Crown sits atop all, unifying them by means of a single institution. This Crown has remained both a symbol of strength and a connection to Canada’s historical roots. The roots of the Crown run deep and can be traced as far back as the sixteenth century, when the kings of France first established the Crown in Canada in Nouvelle-France. -

Architypes Vol. 15 Issue 1, 2006

ARCHITYPES Legal Archives Society of Alberta Newsletter Volume 15, Issue I, Summer 2006 Prof. Peter W. Hogg to speak at LASA Dinners. Were rich, we have control over our oil and gas reserves and were the envy of many. But it wasnt always this way. Instead, the story behind Albertas natural resource control is one of bitterness and struggle. Professor Peter Hogg will tell us of this Peter W. Hogg, C.C., Q.C., struggle by highlighting three distinct periods in Albertas L.S.M., F.R.S.C., scholar in history: the provinces entry into Confederation, the Natural residence at the law firm of Resource Transfer Agreement of 1930, and the Oil Crisis of the Blake, Cassels & Graydon 1970s and 1980s. Its a cautionary tale with perhaps a few LLP. surprises, a message about cooperation and a happy ending. Add in a great meal, wine, silent auction and legal kinship and it will be a perfect night out. Peter W. Hogg was a professor and Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School at York University from 1970 to 2003. He is currently scholar in residence at the law firm of Blake, Cassels & Canada. Hogg is the author of Constitutional Law of Canada Graydon LLP. In February 2006 he delivered the opening and (Carswell, 4th ed., 1997) and Liability of the Crown (Carswell, closing remarks for Canadas first-ever televised public hearing 3rd ed., 2000 with Patrick J. Monahan) as well as other books for the review of the new nominee for the Supreme Court of and articles. He has also been cited by the Supreme Court of Canada more than twice as many times as any other author. -

Michael Nash, the Removal of Judges Under the Act of Settlement

PLEASE NOTE This is a draft paper only and should not be cited without the author’s express permission The Removal of Judges under the Act of Settlement (1701) Michael Nash This paper will consider the operation of the Act, the processes adopted, and the consequential outcomes. It is perhaps worth considering for a moment how important in consequence the Act was. And yet how little enthusiasm there was for it at the time, and how its passing was, in the words of Wellington later, “a damn near thing”. The Act only passed Parliament narrowly. It is said that it was carried by one vote only in Committee in the House of Commons. It is certain that the Act itself passed in the House of Commons “nemine contradicente” on May 14, 1701, but the Bill was but languidly supported. Many of the members, never more than 50 or 60 (out of a full house of 513) appear to have felt that the calling of a stranger to the throne was detestable, but the lesser of two evils. So the Bill was passed by 10% of the members. The passing of the Act is surrounded by myth, and records were then imperfectly kept, but Sir John Bowles, who introduced the Bill, was described as “a member of very little weight and authority”, who was even then thought to be disordered in his mind, and who eventually died mad! (1) Some of the great constitutional documents have been considered in a similar light: for example, the Second Reform Act in 1867. Smith, in a history of this Act, concludes that the bill survived “because a majority of the members of both Houses…dared not throw it out. -

Paul J. Lawrence Fonds PF39

FINDING AID FOR Paul J. Lawrence fonds PF39 User-Friendly Archival Software Tools provided by v1.1 Summary The "Paul J. Lawrence fonds" Fonds contains: 0 Subgroups or Sous-fonds 4 Series 0 Sub-series 0 Sub-sub-series 2289 Files 0 File parts 40 Items 0 Components Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................Biographical/Sketch/Administrative History .........................................................................................................................54 .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................................Scope and Content .........................................................................................................................54 ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Hauraki-Waikato

Hauraki-Waikato Published by the Parliamentary Library July 2009 Table of Contents Hauraki-Waikato: Electoral Profile......................................................................................................................3 2008 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................4 2008 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................4 2005 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................5 2005 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................5 Voter Enrolment and Turnout 2005, 2008 .......................................................................................................6 Hauraki-Waikato: People ...................................................................................................................................7 Population Summary......................................................................................................................................7 Age Groups of the Māori Descent Population .................................................................................................7 Ethnic Groups of the Māori Descent Population..............................................................................................7