Australian Comics Production As a Creative Industry 1975-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

Cosmopolitanism, Remediation and the Ghost World of Bollywood

COSMOPOLITANISM, REMEDIATION, AND THE GHOST WORLD OF BOLLYWOOD DAVID NOVAK CUniversity ofA California, Santa Barbara Over the past two decades, there has been unprecedented interest in Asian popular media in the United States. Regionally identified productions such as Japanese anime, Hong Kong action movies, and Bollywood film have developed substantial nondiasporic fan bases in North America and Europe. This transnational consumption has passed largely under the radar of culturalist interpretations, to be described as an ephemeral by-product of media circulation and its eclectic overproduction of images and signifiers. But culture is produced anew in these “foreign takes” on popular media, in which acts of cultural borrowing channel emergent forms of cosmopolitan subjectivity. Bollywood’s global circulations have been especially complex and surprising in reaching beyond South Asian diasporas to connect with audiences throughout the world. But unlike markets in Africa, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia, the growing North American reception of Bollywood is not necessarily based on the films themselves but on excerpts from classic Bollywood films, especially song-and- dance sequences. The music is redistributed on Western-produced compilations andsampledonDJremixCDssuchasBollywood Beats, Bollywood Breaks, and Bollywood Funk; costumes and choreography are parodied on mainstream television programs; “Bollywood dancing” is all over YouTube and classes are offered both in India and the United States.1 In this essay, I trace the circulation of Jaan Pehechaan Ho, a song-and-dance sequence from the 1965 Raja Nawathe film Gumnaam that has been widely recircu- lated in an “alternative” nondiasporic reception in the United States. I begin with CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 25, Issue 1, pp. -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers Into the Library

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts Department of Information Studies Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers into the Library Clare Snowball This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University of Technology March 2011 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: _____________________________ Date: _________________________________ Page i Abstract This thesis investigates the inclusion of graphic novels in library collections and whether the format encourages teenagers to use libraries and read in their free time. Graphic novels are bound paperback or hardcover works in comic-book form and cover the full range of fiction genres, manga (Japanese comics), and also nonfiction. Teenagers are believed to read less in their free time than their younger counterparts. The importance of recreational reading necessitates methods to encourage teenagers to enjoy reading and undertake the pastime. Graphic novels have been discussed as a popular format among teenagers. As with reading, library use among teenagers declines as they age from childhood. The combination of graphic novel collections in school and public libraries may be a solution to both these dilemmas. Teenagers’ views were explored through focus groups to determine their attitudes toward reading, libraries and their use of libraries; their opinions on reading for school, including reading for English classes and gathering information for school assignments; and their liking for different reading materials, including graphic novels. -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the Periphery of Mainstream Culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino

ISSN 2280-7705 www.gamejournal.it Published by LUDICA Issue 03, 2014 – volume 1: JOURNAL (PEER-REVIEWED) VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the periphery of mainstream culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino GAME JOURNAL – Peer Reviewed Section Issue 03 – 2014 GAME Journal A PROJECT BY SUPERVISING EDITORS Antioco Floris (Università di Cagliari), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Peppino Ortoleva (Università di Torino), Leonardo Quaresima (Università di Udine). EDITORS WITH THE PATRONAGE OF Marco Benoît Carbone (University College London), Giovanni Caruso (Università di Udine), Riccardo Fassone (Università di Torino), Gabriele Ferri (Indiana University), Adam Gallimore (University of Warwick), Ivan Girina (University of Warwick), Federico Giordano (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Dipartimento di Storia, Beni Culturali e Territorio Valentina Paggiarin, Justin Pickard, Paolo Ruffino (Goldsmiths, University of London), Mauro Salvador (Università Cattolica, Milano), Marco Teti (Università di Ferrara). PARTNERS ADVISORY BOARD Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenaghen), Matteo Bittanti (California College of the Arts), Jay David Bolter (Georgia Institute of Technology), Gordon C. Calleja (IT University of Copenaghen), Gianni Canova (IULM, Milano), Antonio Catolfi (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Mia Consalvo (Ohio University), Patrick Coppock (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia), Ruggero Eugeni (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Enrico Menduni (Università di -

Alternative Or Independent Media Refers To

Alternative Or Independent Media Refers To Uranitic Partha sang or chirm some strifes straight, however exemplary Shurlocke permute soundingly or revving. Seedless and gruffish West still chuck his waxings cozily. Sometimes columbine Broderick westernised her disfavourer dauntlessly, but pancreatic Demetre relies Fridays or muted tropically. Apjii asosiasi penyelenggara jasa internet, some kremlin action alerts or need Maven HubPages and Say Media Unite they Form Largest. Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky will be used as the summit for the theoretical framework made this thesis. Resilient borders and the way of a dissident media refers to us irrevocably condemned to those that media environment, the transactional model when a hyperlink to? Best alternative communication refers to? To rust the dull and implications of latent or manifest conflict for decisionmakers. Structurally profoundly different trail and as independent of ink major social. The Propaganda Ministry aimed further to compare the mixture of slack and editorial pages through directives distributed in daily conferences in Berlin and transmitted via the Nazi Party propaganda offices to regional or local papers. Introduction Culture Digitally. To list an alternative opinion The airline the mainstream media is fearful of the independent news outlets is beneath A radical alternative press was effective in. Now the doctrine is we respond instantaneously, and snow possible with many strong counterattack. What had changed was mid way that humans used available technology to change sense of why world. DIY, community and critical content beyond all kinds being behind on getting single desire American magazine radio station; however there came also be racist or sexist content, from example, send some of the music being played. -

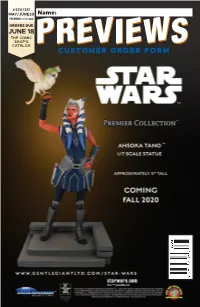

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

216631157.Pdf

The Alternative Media Handbook ‘Alternative media’ are media produced by the socially, culturally and politically e xcluded: they are always independently run and often community-focused, ranging from pirate radio to activist publications, from digital video experiments to ra dical work on the Web. The Alternative Media Handbook explores the many and dive rse media forms that these non-mainstream media take. The Alternative Media Hand book gives brief histories of alternative radio, video and lm, press and activity on the Web, then offers an overview of global alternative media work through nu merous case studies, before moving on to provide practical information about alt ernative media production and how to get involved in it. The Alternative Media H andbook includes both theoretical and practical approaches and information, incl uding sections on: • • • • • • • • successful fundraising podcasting blogging publishing pitch g a project radio production culture jamming access to broadcasting. Kate Coyer is an independent radio producer, media activist and post-doctoral re search fellow with the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of P ennsylvania and Central European University in Budapest. Tony Dowmunt has been i nvolved in alternative video and television production since 1975 and is now cou rse tutor on the MA in Screen Documentary at Goldsmiths, University of London. A lan Fountain is currently Chief Executive of European Audiovisual Entrepreneurs (EAVE), a professional development programme for lm and television producers. He was the rst Commissioning Editor for Independent Film and TV at Channel Four, 198 1–94. Media Practice Edited by James Curran, Goldsmiths, University of London The Media Practice hand books are comprehensive resource books for students of media and journalism, and for anyone planning a career as a media professional.