On Originale by Mark Bloch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

På Sporet Af Else Marie Pades Konkrete Musik

A-PDF Merger DEMO : Purchase from www.A-PDF.com to remove the watermark På sporet af Else Marie Pades konkrete musik En analyse af den æstetiske forbindelse mellem Else Marie Pades Symphonie magnétophonique og Pierre Schaeffers musique concrète Speciale ved Stine Kvist Jeppesen Afdeling for Musikvidenskab Institut for Æstetiske Fag, Aarhus Universitet Vejleder: Erling Kullberg Den 24. juli 2010 Forsidebilledet er en visualisering af en passage fra Else Marie Pades Symphonie magnétophonique, skabt af den grafiske designer Lisbeth Damgaard i 2006. Damgaards visuelle fortolkning af musikken er skabt med udgangspunkt i spektrogrammer fra det originale værk. De blå, brune, gule og grønne farver illustrerer lyden af hhv. lærketrille, fuglesang, mælkemandsfløjt og mælkeflasker, som er de lyde, der indleder Pades Symphonie magnétophonique. Billedet er hentet fra bogen Else Marie Pade og Symphonie magnétophonique, der er redigeret af Inge Bruland i 2006. Abstract This master thesis investigates to which extend it is possible to categorise the works of Danish composer Else Marie Pade (1924‐) as musique concrète, a term often used in Danish music research and critique to descibe Pade’s music. The thesis presumes that the appraisal of Pade’s music as musique concrète rests on a reduced understanding of musique concrète, inasmuch as this has only been sporadic and cursorily accounted for in a Danish context. To make a scholarly qualified reappraisal of Pade’s pioneer works of musique concrète, the master thesis will investigate the aesthetic link between Pades Symphonie magnétophonique and the music and aesthetics of the French composer and founder of musique concrète Pierre Schaeffer. The first two parts of the thesis will include an introduction to Pade’s work as well as an account and discussion of the reception of her music. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

Stockhausen Works for Orchestra

composed 37 works for orchestra from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0]2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Duration Publisher CD of the Stockhausen Complete Edition 1950 DREI LIEDER (THRE E SONGS [19 ’26”] U.E. e1 for alto voice and chamber orchestra ( cond. )(Universal Edition ) (fl. / 2 cl. / bsn. / tp. / trb. / 2 perc. / piano / elec. harpsichord / strings) 1951 FORMEL (FORMULA) [12 ’57”] U. E e2 for orchestra [28 players] ( cond. ) 1952 SPIEL (PLAY) [16 ’01”] U. E. e2 for orchestra ( cond. ) 195 2/ PUNKTE (POINTS) [ca. 27 ’] U. E. e2 E81‰ 1962 / 1993 for orchestra ( cond. ) 195 2 KONTRA-PUNKTE (COUNTER-POINTS) [14 ’13”] U. E. e4 to 53 for 10 instruments ( cond. ) (fl. / cl. / bass cl. / bsn. / tp. / trb. / piano / harp / vl. / vc.) 195 5 GRUPPEN (GROUPS) [24 ’25”] U. E. e5 to 57 for 3 orchestras ( 3 cond. ) 195 9 CARRÉ [ca. 36’] U. E. e5 to 60 for 4 orchestras and 4 choirs ( 4 cond. ) 196 2 MOMENTE (MOMENTS) [113’] St. e7 E80‰ to 64 for solo soprano, 4 choir groups (Stockhausen-Verlag ) (finished in ’69) and 13 instrumentalists ( cond. ) 1964 MIXTUR (MIXTURE) [ca. 2 x 27’] U. E for orchestra, 4 sine-wave generators and 4 ring modulators ( cond. ) 1964 / MIXTUR (MIXTURE) [2 x 27’] U. E. e8 1967 for small orchestra (cond. -

Artists Books: a Critical Survey of the Literature

700.92 Ar7 1998 artists looks A CRITICAL SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE STEFAN XL I M A ARTISTS BOOKS: A CRITICAL SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE < h'ti<st(S critical survey °f the literature Stefan ^(lima Granary books 1998 New york city Artists Books: A Critical Survey of the Literature by Stefan W. Klima ©1998 Granary Books, Inc. and Stefan W. Klima Printed and bound in The United States of America Paperback original ISBN 1-887123-18-0 Book design by Stefan Klima with additional typographic work by Philip Gallo The text typeface is Adobe and Monotype Perpetua with itc Isadora Regular and Bold for display Cover device (apple/lemon/pear): based on an illustration by Clive Phillpot Published by Steven Clay Granary Books, Inc. 368 Broadway, Suite 403 New York, NY 10012 USA Tel.: (212) 226-3462 Fax: (212) 226-6143 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.granarybooks.com Distributed to the trade by D.A.R / Distributed Art Publishers 133 6th Avenue, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10013-1307 Orders: (800) 338-BOOK Tel.: (212) 627—1999 Fax: (212) 627-9484 IP 06 -ta- Adrian & Linda David & Emily & Ray (Contents INTRODUCTION 7 A BEGINNING 12 DEFINITION 21 ART AS A BOOK 41 READING THE BOOK 6l SUCCESSES AND/OR FAILURES 72 BIBLIOGRAPHIC SOURCES 83 LIST OF SOURCES 86 INTRODUCTION Charles Alexander, having served as director of Minnesota Center for Book Arts for twenty months, asked the simple question: “What are the book arts?”1 He could not find a satisfactory answer, though he tried. Somewhere, in a remote corner of the book arts, lay artists books. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

New 2014–2017

Stockhausen-Verlag, 51515 Kürten, Germany www.karlheinzstockhausen.org / [email protected] NEW 2014–2017 New scores (can be ordered directly online at www.stockhausen-verlag.com): TELEMUSIK (TELE MUSIC) Electronic Music (English translation) ................................ __________ 96 ¤ (54 bound pages, 9 black-and-white photographs) ORIGINALE (ORIGINALS) Musical Theatre (Textbook) ..................................................... __________ 88 ¤ (48 bound pages, 11 black-and-white photographs) TAURUS-QUINTET for tuba, trumpet, bassoon, horn, trombone .................................... __________ 60 ¤ (folder with score in C, 10 bound pages, cover in colour with Stockhausen’s original drawing, plus performance material: 5 loose-leaf parts for tuba, trumpet, bassoon, horn in F and trombone) CAPRICORN for bass and electronic music ................................................................................ __________ 65 ¤ (60 bound pages, cover in colour) KAMEL-TANZ (CAMEL-DANCE) .............................................................................................. __________ 30 ¤ (of WEDNESDAY from LIGHT) for bass, trombone, synthesizer or tape and 2 dancers (20 bound pages, cover in colour) MENSCHEN, HÖRT (MANKIND, HEAR) .................................................................................. __________ 30 ¤ (of WEDNESDAY from LIGHT) for vocal sextet (2 S, A, T, 2 B) (24 bound pages, cover in colour with Stockhausen’s original drawing) HYMNEN (ANTHEMS) Electronic and Concrete Music – study -

For Januaryfebruary 1991 Has Covers by Joni Ed to Elvis' Birthday

ART READER This is a regional periodical that deserves a national reading! for JanuaryFebruary 1991 has covers by Joni ed to Elvis' birthday. Political and social Meaning: Contemporary Art Issues, #9, May 1991 in- issues are addressed in the MarchIApril issue. Included are cludes articles by Charles Bernstein, Joseph Nechvatd, articles culled from panel discussion culled from "Art in Daryl Chin, as well as book reviews by Whitney Chadwick, Context" series held at Atlanta College of Art in the fall of Robert C. Morgan, and others. 1 Reflex (Seattle) for May/June is devoted to Lacan & for May/June 1991 has a theme section on Fe&sm,or Cliff Notes to . Also included is an Mail Art with contributions from Chuck Welch, John Held, interview with Buster Simpson, among a myriad of gallery Jr., Mark Bloch, Mimi Holmes, Mark Kingsley, Guy Bleus reviews, news and perceptive writing. and others. (Art Papers is published in Atlanta, GA). Video Guide (Vancouver, Spring 1991) is devoted for the for Winter 1990 includes an article on Bud- most part to the treatment of Asians in Canada in art, dhist Art, with lots of illustrations of palm-leaf manuscripts. broadcasting, advertising, etc. A bargain ($15.00 for five In the same issue, Buzz Spector discusses Susan E. King's I issues) from 1102 Homer St., Vancouver, BC, Canada V6B e Summer m Paris. 2x6. is celebrating its 10th birthday by including all Miabelb, basically a woman's magazine, has had some those wonderful avant-garde poets, artists and writers in the delicious contributions which entice one into continuing to tallest and narrowest magazine ever printed--with contribu- subscribe. -

Tuning in Opposition

TUNING IN OPPOSITION: THE THEATER OF ETERNAL MUSIC AND ALTERNATE TUNING SYSTEMS AS AVANT-GARDE PRACTICE IN THE 1960’S Charles Johnson Introduction: The practice of microtonality and just intonation has been a core practice among many of the avant-garde in American 20th century music. Just intonation, or any system of tuning in which intervals are derived from the harmonic series and can be represented by integer ratios, is thought to have been in use as early as 5000 years ago and fell out of favor during the common practice era. A conscious departure from the commonly accepted 12-tone per octave, equal temperament system of Western music, contemporary music created with alternate tunings is often regarded as dissonant or “out-of-tune,” and can be read as an act of opposition. More than a simple rejection of the dominant tradition, the practice of designing scales and tuning systems using the myriad options offered by the harmonic series suggests that there are self-deterministic alternatives to the harmonic foundations of Western art music. And in the communally practiced and improvised performance context of the 1960’s, the use of alternate tunings offers a Johnson 2 utopian path out of the aesthetic dead end modernism had reached by mid-century. By extension, the notion that the avant-garde artist can create his or her own universe of tonality and harmony implies a similar autonomy in defining political and social relationships. In the early1960’s a New York experimental music performance group that came to be known as the Dream Syndicate or the Theater of Eternal Music (TEM) began experimenting with just intonation in their sustained drone performances. -

Files Events/Artists

Files events/artists ____________________________________________________________________________________________ tuesday 16 > sunday 21 april 3 pm > 9 pm Garage Pincio tuesday 16 april 6 pm opening Marcel Türkowsky/Elise Florenty (D/F) We, the frozen storm audio-visual installation production Xing/Live Arts Week with the collaboration of Bologna Sotterranea/Associazione Amici delle Vie d'Acqua e dei Sotterranei di Bologna We, the frozen storm is the title of the new and site-specific installation conceived for the evocative spaces of the tunnels of the Pincio shelter, under the Montagnola Park. The title is inspired by Bildbeschreibung (Explosion of memory/description of an image) by Heiner Muller. " What could be the travel from the self to the other? Imagine to face portraits of characters that carry multidentity-stories: from the old to the new world, from the factual to the fictional, from the undead past to the speculative future. A delirium embracing the cosmic world. This travel will be colorful, hypnotic, engaging, pushing the spectator into unconscious meandering and disorientation." For their first exhibition in Italy, Florenty and Türkowsky have composed a work made up of video projections, sounds, glows and shadows, marking an important first step in the research currently underway after the great project Through Somnambular Laws (2011) toward a new series of works. Elise Florenty & Marcel Türkowsky. Since the beginning of their collaboration in 2005 Elise Florenty - with a background in visual arts and film - and Marcel Türkowsky - with a background in philosophy, ethnomusicology and, later, visual art – have shared their passion for the power of language through songs, writing and instructions. -

PDF Download Stockhausen on Music Ebook, Epub

STOCKHAUSEN ON MUSIC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Karlheinz Stockhausen,Robin Maconie | 220 pages | 01 Sep 2000 | Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd | 9780714529189 | English | London, United Kingdom Stockhausen on Music PDF Book English translation of "Symbolik als kompositorische Methode in den Werken von Karlheinz Stockhausen". Die Zeit 9 December. After completing Licht , Stockhausen embarked on a new cycle of compositions based on the hours of the day, Klang "Sound". There's more gnarly theory to get stuck into with Karlheinz than with almost anyone else in music history, thanks to his own writings and the mini-industry of Stockhausen arcana and analysis out there. Custodis, Michael. Ars Electronica. Cross, Jonathan. Iddon, Martin. Selected Correspondence , vol. The sounds they play are mixed together with the sounds of the helicopters and played through speakers to the audience in the hall. Grant, M[orag] J[osephine], and Imke Misch eds. Hartwell, Robin. Mixtur was a live work for orchestra, sine wave generators, and ring modulators, with the latter resurfacing again in in Mikrophonie II, also scored for chorus and Hammond organ. English translation by Donato Totaro under the same title here. Otto Luening. Winter : — The lectures which are the heart of this book clarified some of Stockhausen's ideas and methods for me, although some points remain obscure. Michele Marelli. Very good insights into Stockhausen's process and thinking. What does it mean, my music? No trivia or quizzes yet. Westport, Conn. Kaletha, Holger. Electronic Folk International. Rathert, Wolfgang. Kraftwerk: I Was a Robot. The Musical Quarterly 61, no. Le Souffle du temps: Quodlibet pour Karlheinz Stockhausen. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen

What to Expect: Welcome to KLANG! There is a lot happening Elizabeth Huston and Analog Arts Present today, so we recommend you take a quick look at this packet to orient yourself. Inside you will find the schedule and location Karlheinz Stockhausen of performances, the schedule and location of talks, interviews, and Q&As, and a guide to all amenities that will be available as you navigate this marathon. First, let’s start with the rules. The day is broken up into four sections. You may have purchased a ticket for just one section, KLANG or you may have purchased an all-day pass. Either way, please THE 24 HOURS OF THE DAY familiarize yourself with the rules for each section, as each is a distinctly different experience. PHILADELPHIA, PA • April 7–8, 2018 Welcome to KLANG: At 10am sharp you will be welcomed by a welcome to enter and exit the spaces during performances. At performance of all three versions of HARMONIEN performed in all other times, please be courteous and enter and exit between La Peg, the Theater, and the Studio simultaneously. Feel free to performances. wander between the spaces, eventually settling in the Studio for… KLANG Immersion (4pm–7pm): A mix between KLANG up Close and KLANG in Concert, this time period showcases some of the KLANG up Close (10am–1pm): This time period is an opportu- most well known parts of KLANG, while still allowing the audi- nity to have an intimate concert experience with KLANG. This ence to be up close with the music. Taking place entirely in the will take place entirely in the Studio. -

Artists in the U.S

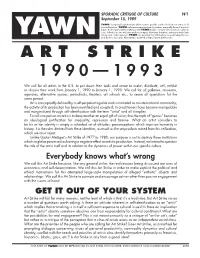

SPORADIC CRITIQUE OF CULTURE Nº1 September 15, 1989 YAWN is a sporadic communiqué which seeks to provide a critical look at our culture in all its manifestations. YAWN welcomes responses from its readers, especially those of a critical nature. Be forewarned that anything sent to YAWN may be considered for inclusion in a future issue. Submissions are welcome and encouraged. Monetary donations are requested to help defray costs. Subscriptions to YAWN are available for $10 (cash or unused stamps) for one YAWN year by first class mail. All content is archived at http://yawn.detritus.net/. A R T S T R I K E 1 9 9 0 — 1 9 9 3 We call for all artists in the U.S. to put down their tools and cease to make, distribute, sell, exhibit or discuss their work from January 1, 1990 to January 1, 1993. We call for all galleries, museums, agencies, alternative spaces, periodicals, theaters, art schools etc., to cease all operations for the same period. Art is conceptually defined by a self-perpetuating elite and is marketed as an international commodity; the activity of its production has been mystified and co-opted; its practitioners have become manipulable and marginalized through self-identification with the term “artist” and all it implies. To call one person an artist is to deny another an equal gift of vision; thus the myth of “genius” becomes an ideological justification for inequality, repression and famine. What an artist considers to be his or her identity is simply a schooled set of attitudes; preconceptions which imprison humanity in history.