Senegal Cultural Field Guide Ethnic Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo

SENEGAL MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo. Disciples of the Baye Fall Dahira of Cheikh Seye Baye perform a religious ceremony, drumming, dancing and singing prayers. While in other countries fundamentalists may prohibit music, it is an integral part of the religious practice in Sufism. Sufism is a form of Islam practiced by the majority of the population of Senegal, where 95% of the country’s inhabitants are Muslim Based on the teachings of religious leader Amadou Bamba, who lived from the mid 19th century to the early 20th, Sufism preaches pacifism and the goal of attaining unity with God According to analysts of international politics, Sufism’s pacifist tradition is a factor that has helped Senegal avoid becoming a theatre of Islamist terror attacks Sufism also teaches tolerance. The role of women is valued, so much so that within a confraternity it is possible for a woman to become a spiritual leader, with the title of Muqaddam Sufism is not without its critics, who in the past have accused the Marabouts of taking advantage of their followers and of mafia-like practices, in addition to being responsible for the backwardness of the Senegalese economy In the courtyard of Cheikh Abdou Karim Mbacké’s palace, many expensive cars are parked. They are said to be gifts of his followers, among whom there are many rich Senegalese businessmen who live abroad. The Marabouts rank among the most influential men in Senegal: their followers see the wealth of thei religious leaders as a proof of their power and of their proximity to God. -

(JHSSS) Nigeria-Benin Border Closure

Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies (JHSSS) Website: www.jhsss.org ISSN: 2663-7197 Original Research Article Nigeria-Benin Border Closure: Implications for Economic Development in Nigeria Ola Abegunde1* & Fabiyi, R.2 1Ekiti State University, Department of Political Science, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2Research Officer, Garnet Aught Global, Lagos, Nigeria Corresponding Author: Ola Abegunde, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History Nigeria remains the major international market for foreign earnings for many Received: June 02, 2020 countries in the word. The Republic of Benin in the sub-Sahara Africa is majorly Accepted: July 13, 2020 dependent on Nigeria for the survival of her international trade. This study Volume: 2 investigates the Nigeria-Benin border closure and its implications on Nigerian Issue: 4 economic development. Secondary data were used for the research, and content analysis was the instrument used in analysis of the data generated from the KEYWORDS study. Smuggling was confirmed to occur on the Nigeria-Benin border and was perpetrated by residents of both countries. Though legal commercial activities Nigeria-Benin, Custom service, still take place on the same border. Illegal activities on the Nigeria-Benin border border closure, smuggling, include cross-border crimes like banditry and kidnapping as well as trafficking in economic development. human beings, contraband goods, illegal arms and ammunition, illicit drugs, and diverted petroleum products. All these transactions constitute serious threat to Nigeria’s national security and affects it economy. Therefore, the illegal activities on the border led to its closure by the Nigerian federal government in August 2019. The effects of the border closure on Nigerian socio-economic includes decrease in all smuggling activities and other cross-border crimes. -

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟S Center on Applied Feminism for Its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟s Center on Applied Feminism for its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference. “Applying Feminism Globally.” Feminism from an African and Matriarchal Culture Perspective How Ancient Africa’s Gender Sensitive Laws and Institutions Can Inform Modern Africa and the World Fatou Kiné CAMARA, PhD Associate Professor of Law, Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, SENEGAL “The German experience should be regarded as a lesson. Initially, after the codification of German law in 1900, academic lectures were still based on a study of private law with reference to Roman law, the Pandectists and Germanic law as the basis for comparison. Since 1918, education in law focused only on national law while the legal-historical and comparative possibilities that were available to adapt the law were largely ignored. Students were unable to critically analyse the law or to resist the German socialist-nationalism system. They had no value system against which their own legal system could be tested.” Du Plessis W. 1 Paper Abstract What explains that in patriarchal societies it is the father who passes on his name to his child while in matriarchal societies the child bears the surname of his mother? The biological reality is the same in both cases: it is the woman who bears the child and gives birth to it. Thus the answer does not lie in biological differences but in cultural ones. So far in feminist literature the analysis relies on a patriarchal background. Not many attempts have been made to consider the way gender has been used in matriarchal societies. -

BANK of AFRICA SENEGAL Prie Les Personnes Dont Les Noms Figurent

COMMUNIQUE COMPTES INACTIFS BANK OF AFRICA SENEGAL prie les personnes dont les noms figurent sur la liste ci- dessous de bien vouloir se présenter à son siège (sis aux Almadies, Immeuble Elan, Rte de Ngor) ou dans l’une de ses agences pour affaire les concernant AGENCE DE NOM NATIONALITE CLIENT DOMICILIATION KOUASSI KOUAME CELESTIN COTE D'IVOIRE ZI PARTICULIER 250383 MME SECK NDEYE MARAME SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100748 TOLOME CARLOS ADONIS BENIN INDEPENDANCE 102568 BA MAMADOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101705 SEREME PACO BURKINA FASO INDEPENDANCE 250535 FALL IBRA MBACKE SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100117 NDIAYE IBRAHIMA DIAGO SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 251041 KEITA FANTA GOGO SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101860 SADIO MAMADOU SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 250314 MANE MARIAMA SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 103715 BOLHO OUSMANE ROGER NIGER INDEPENDANCE 103628 TALL IBRAHIMA SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100812 NOUCHET FANNY J CATHERINE SENEGAL MERMOZ 104154 DIOP MAMADOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100893 NUNEZ EVELYNE SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101193 KODJO AHIA V ELEONORE COTE D'IVOIRE PARCELLES ASSAINIES 270003 FOUNE EL HADJI MALICK SENEGAL MERMOZ 105345 AMON ASSOUAN GNIMA EMMA J SENEGAL HLM 104728 KOUAKOU ABISSA CHRISTIAN SENEGAL PARCELLES ASSAINIES 270932 GBEDO MATHIEU BENIN INDEPENDANCE 200067 SAMBA ALASSANE SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 251359 DIOUF LOUIS CHEIKH SENEGAL TAMBACOUNDA 960262 BASSE PAPE SEYDOU SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 253433 OSENI SHERIFDEEN AKINDELE SENEGAL THIES 941039 SAKERA BOUBACAR FRANCE DIASPORA 230789 NDIAYE AISSATOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 111336 NDIAYE AIDA EP MBAYE SENEGAL LAMINE GUEYE -

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

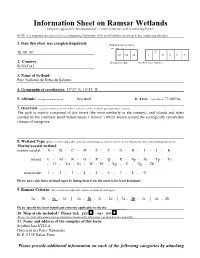

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10. -

Senegal Page 155 8

© 2003 Center for Reproductive Rights www.reproductiverights.org formerly the Center for Reproductive Law and Policy LAWS AND POLICIES AFFECTING THEIR REPRODUCTIVE LIVES SENEGAL PAGE 155 8. Senegal Statistics GENERAL Population I The total population of Senegal is approximately 9 million.1 I The average annual population growth rate between 1995 and 2000 is estimated to be 2.7%.2 I In 1995, women comprised 52% of the population.3 I In 1995, 42% of the population resided in urban areas.4 Territory I Senegal covers an area of 196,722 square kilometers.5 Economy I In 1997,the estimated per capita gross national product (GNP) was U.S.$550.6 I Between 1990 and 1997,the average annual growth rate of the gross domestic product (GDP) was 2.4%.7 I Approximately 40% of the population have access to primary health care.8 I The government allocates 6.5% of the national budget to the health sector.9 Employment I In 1997,women comprised 43% of the workforce, compared to 42% in 1980.10 I The distribution of women in the different sectors of the economy in 1994 was as follows: 87% in agriculture, 3% in industry,and 10% in services.11 I In 1991, the unemployment rate for women increased from 23.1% in 1988 to 26.6%.12 WOMEN’S STATUS I In 1997,the average life expectancy for women was 52.3 years, compared to 50.3 for men.13 I The adult illiteracy rate was 77% for women, compared to 57% for men.14 I In 1997, 46% of married women lived in polygamous unions.15 I The average age at first marriage for women aged 25-49 was 17.4 years.16 Among these women, 15% were married upon reach- ing 15 years, and 50% upon reaching 18 years.17 FEMALE MINORS AND ADOLESCENTS I Approximately 45% of the population is under 15 years old.18 I In 1995, primary school enrollment for school-aged girls was 50%, compared to 67% for boys. -

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance Perspectives from Women and Local Populations August 2019 Content 3. Acronyms & Abbreviations 4. Acknowledgements 5. Foreword 7. Cry For Action Of The Women Of Casamance! 8. Preface 9. Introduction 9. Context 11. Historical background of the conflict and the peace process 13. The Conflict’s Impacts On Local Populations, Women And Youth 13. Socioeconomic and environmental impacts 15. Casamance populations’ perceptions and feelings of exclusion 17. The conflict’s specific impacts on women 18. A permanent insecurity 19. Strategies And Perspectives From Civil Society 20. Civil society actors 21. Addressing challenges and establishing peace 23. Actions and approaches 25. Conditions for effective and inclusive participation 26. Women’s participation in peace processes 26. The mediation role of women of Casamance 27. La Plateforme des Femmes pour la Paix en Casamance (PFPC) 28. Senegambia Forum 29. Breaking down barriers and strengthening support across women throughout Senegal 30. Recommendations for a definitive & sustainable peace in Casamance 34. Bibliography 35. Annexes 49. Endnotes Acronyms & Abbreviations AFUDES Association of United Brothers for the Economic and Social Development of the Fogny ASC Sports and Cultural Association AJAEDO Association des Jeunes Agriculteurs et Éleveurs du Département d'Oussouye AJWS American Jewish World Service (NGO) ANRAC Agence nationale pour la Relance des Activités économiques en Casamance ANSD Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie -

Guinea-Bissau After Vieira: Challenges and Opportunities

THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS 20/1999 Guinea-Bissau after Vieira: Challenges and Opportunities On 7 June 1998, an army mutiny led by former Chief of Staff, General Ansumane Mane, plunged the Republic of Guinea-Bissau into a devastating civil war. The coup aimed to oust President Joao Bernardo Vieira, who had come to power in a military coup against Luis Cabral in 1980 and had subsequently won the country's first multiparty elections in 1994. The civil war that followed Mane's mutiny changed the framework of the ongoing transformation process in the former socialist-orientated Guinea-Bissau. It also engulfed the subregion drawing Senegal, Guinea and The Gambia into the power struggle in Guinea- Bissau. In May 1999, after a peace process had already been did not install a military regime after he came to negotiated and partially implemented, Mane's forces power. With the beginning of democratic transition launched another attack on Vieira, and finally in 1990, the military lost its remaining privileges and succeeded in ousting the incumbent leader. Although became part of the marginalised population. Major this coup can be seen as a setback for peace and sections of the army started relying on proceeds from reconciliation in Guinea-Bissau, the new political illicit arms deals with the Casamance rebels and situation that resulted from Vieira's overthrow at least cannabis sales. provided a chance to end a hitherto paralysing state of 'no peace-no war' — akin to the Angolan situation The regional dimension after the Lusaka Accords. The new power G iven Mane's control over major sections of the army, constellation under Mane may well give Vieira's Vieira had to fight the rebellion with the military rather disappointing democratisation assistance of Guinea (400 soldiers) and process fresh impetus. -

Path(S) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community”

“Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” By Jaison Carter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair Professor Charles Hirschkind Professor Stefania Pandolfo Professor Ula Y. Taylor Spring 2018 Abstract “Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” by Jaison Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair The Mustafawiyya Tariqa is a regional spiritual network that exists for the purpose of assisting Muslim practitioners in heightening their level of devotion and knowledges through Sufism. Though it was founded in 1966 in Senegal, it has since expanded to other locations in West and North Africa, Europe, and North America. In 1994, protegé of the Tariqa’s founder and its most charismatic figure, Shaykh Arona Rashid Faye al-Faqir, relocated from West Africa to the United States to found a satellite community in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. This location, named Masjidul Muhajjirun wal Ansar, serves as a refuge for traveling learners and place of worship in which a community of mostly African-descended Muslims engage in a tradition of remembrance through which techniques of spiritual care and healing are activated. This dissertation analyzes the physical and spiritual trajectories of African-descended Muslims through an ethnographic study of their healing practices, migrations, and exchanges in South Carolina and in Senegal. By attending to manner in which the Mustafawiyya engage in various kinds of embodied religious devotions, forms of indebtedness, and networks within which diasporic solidarities emerge, this project explores the dispensations and transmissions of knowledge to Sufi practitioners across the Atlantic that play a part in shared notions of Black Muslimness. -

2014 Mowglis Call

The Mowglis Call 2014 Nick Robbins .................. [email protected] Holly Taylor ................................ [email protected] Tommy Greenwell ........ [email protected] FIND US ON FACEBOOK! Please join our group to keep up with the latest Mowglis events, see photos from last summer, and reconnect with old friends. We’re currently over 460 members strong! www.facebook.com/groups/CampMowglisGroup/ Please send us your email address! Send updates to: [email protected] HOLT-ELWELL MEMORIAL In This Issue FOUNDATION President’s Message ........................................................................2 TRUSTEES Director’s Message ...........................................................................3 Christopher A. Phaneuf Assistant Director’s Letter ..............................................................4 President Remembering Allyn Brown ......................................................... 5-8 Weston, Mass. New Woodworking Shop ................................................................8 Jim Westberg Vice President Wayne King: Doing Good, Doing Well ....................................9-11 Nashua, N.H. Alumni and Recruiting Events ......................................................12 David Tower Kenyon Salo: Leading the Bucket List Life ......................... 15-16 Treasurer Malvern, Pa. Alejandro and Raul Medina-Mora Return to Mowglis ...........17 Richard Morgan 2014 Contributors ................................................................... 18-19 Secretary N. Sandwich, N.H. Alumni