The Exceptional Voting Behavior of Eastern Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Malazgirt Ve Çevresi Yüzey Araştirmasi

MALAZGİRT VE ÇEVRESİ YÜZEY ARAŞTIRMASI Manzikert and Its Vicinity Survey Rüçhan Arık1 Öz Malazgirt’in tarihteki önemi; Anadolu’da, Türkiye Cumhuri- yetine kadar uzanan yaklaşık bin yıllık Türkiye tarihinin başlangı- cını oluşturmasında yatmaktadır. Malazgirt eski çağlardan beri önemini korumuştur. Kent seyyahların ve araştırmacıların dikkati- ni çekmiş; şehirde önemli yapıların; cami, kilise, kale, han, hamam gibi varlığı ortaya konmuştur. Malazgirt, fiziki varlığının dışında, Anadolu Türkleri için simgesel anlam taşımaktadır. Bu denli önemli bir şehirdeki yüzey araştırmamız ilk önce surlar üzerinde yoğunlaşmıştır. Kale çevre- sindeki çalışmalarda çok sayıda seramik ve sikke bulunmuştur. Ertesi yıl, 1988’deki yüzey araştırmamız Malazgirt çevresinde Esenlik ve Molla Kendi köylerinde devam etmiştir. Türkiye kimliğinin başlangıç noktası olan Malazgirt şehrin- de kısa süreliğine yapılan yüzey araştırması tarihi bakımdan zen- ginliğini göstermektedir. Uzun yıllar kendi kaderine terk edilen Malazgirt hak ettiği değeri almayı beklemektedir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Ortaçağ, Malazgirt, Mimari, Seramik Summary The importance of Manzikert in history lies in the beginning of the history of Turkey, which dates back nearly a thousand years to the Republic of Turkey in Anatolia. 1 Prof. Dr., Ankara Üniversitesi Dil Tarih Coğrafya Fakültesi, Emekli Öğretim Üyesi Rüçhan Arık Manzikert has maintained its importance since ancient ti- mes. The city has attracted the attention of travelers and researc- hers who indicates the existance of the importance monuments such as, mosque, church, castle, khan, baths. Apart from its physical existence, Manzikert has symbolic meaning for Anatolian Turks. Our survey in this important city has first concentrated on the walls. Coins and fragments of ceramics were found in the studies around the castle. The following year, in 1998, our surface survey was continued in the environs of Manzi- kert, Esenlik, Molla and Kendi villages. -

Ardahan-Brosur--Ingilizce-Sikistirildi

ARDAHAN: REALM OF HIGH LANDS Ardahan, the realm of highlands, has a distinct geography that of- fers the glories of the past and treasures of the nature together. It is also an undiscovered tourism center with its steep mountains, up- lands covered with endemic flowers, glacial lakes on the foothills of majestic peaks, yellow pine forests, castles and towers, churches, mysterious border towns, and a cultural wealth that reflects the mo- saic of its diversity. Ardahan involves the borders with Georgia and Armenia in the north and northeast, with Kars and Erzurum in the south and southeast, and with Artvin in the west. Most significant elevations are Kısır, Keldağı, Akbaba, Cin, Ilgar, Ahaşen, Uğurlu and Yalnızçam Mountains. On the foothills of these high mountains are the uplands that huddle all kinds of colors within the nature into one place and emerge as orchards. Almost all of the villages in Ardahan have upland, and their dwellers migrate to these high- lands in company with their herds as of June. Certainly one of the most prominent rivers of Ardahan is Kura River. Posof, Karaçay, Değirmendere, Hanak, Kayınlıkdere, Türkmenderesi and Ölçek can be listed as the other local rivers with various sizes. Lake Çıldır, which is the tenth biggest lake in the country and second biggest lake of Eastern Anatolia Region in terms of acreage, and Aktaş river on Georgia border, are among the significant lakes of the province. HISTORY Ardahan region, which was used as a migration way from Caucasus to Anatolia, has a rich historical and cultural background. Especially the castles and towers laying on or nearby deep, long and succes- sive valleys created by Kura River are among the most significant details that convey the traces of the past to present. -

Erciş Tekler Mahallesi Mezarlığı'nda Bulunan Karakoyunlu Dönemi

Iğd Üniv Sos Bil Der / Igd Univ Jour Soc Sci Sayı / No. 23, Temmuz / July 2020 Araştırma Makalesi / Article: 219-245 _____________________________________________________ Erciş Tekler Mahallesi Mezarlığı’nda Bulunan Karakoyunlu Dönemi Mezar Taşları YUSUF ÇETİN a EVREN BİNGÖL b Geliş Tarihi: 18.03.2020 Kabul Tarihi: 21.07.2020 Öz: Türkistan’da boylar halinde yaşayan ve Moğol istilaları so- nucunda Anadolu’ya göç eden Barani veya Baranlu gibi boylar, XIV. yüzyılın ikinci yarısında Bayram Hoca önderliğinde bir araya gelerek Karakoyunlu Devleti’ni kurmuşlardır. Bir asırdan fazla tarih sahnesinde kalan ve devletlerini kurdukları coğraf- yanın Türk yurdu olarak kalması hususunda önemli rol oyna- yan Karakoyunlular için Erciş büyük önem arz etmektedir. Hâkim oldukları coğrafyada önemli faaliyetler gerçekleştirdiği gibi ilk başkentleri Erciş olması münasebetiyle siyasi faaliyetle- rini burada yoğunlaştıran Karakoyunlular, şehrin imarına da büyük önem vermişlerdir. Bugün ilçenin birçok noktasında bu- lunan ve yok olmaya yüz tutmuş bu eserler bir yandan döne- min tarihine ışık tutarken diğer yandan Karakoyunluların sa- natsal alanda geldikleri nokta ile bölgedeki kültürel mirasın et- kileşimi ve gelişimine katkıları hakkında önemli bilgiler sun- maktadır. Erciş ve çevresinde Karakoyunlu dönemine ait kültür varlıklarının önemli bir kolunu tarihi mezarlıklar ve mezar taş- ları oluşturmaktadır. Bu mezarlıklardan birisi de içinde Kara- koyunlu dönemi mezar taşı geleneklerini yansıtan özgün form ve süslemelere sahip mezar taşlarının bulunduğu Tekler -

Traditional Knowledge of Wild Edible Plants of Iğdır Province (East

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae DOI: 10.5586/asbp.3568 ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Publication history Received: 2016-10-06 Accepted: 2017-11-15 Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants Published: 2017-12-28 of Iğdır Province (East Anatolia, Turkey) Handling editor Łukasz Łuczaj, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Rzeszów, Poland Ernaz Altundağ Çakır* Department of Biology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Düzce University, 81620 Konuralp, Düzce, Funding Turkey This research was partially supported by the Research * Email: [email protected] Fund of Istanbul University (project No. 1441) and partially conducted at the author’s own expense. Abstract Iğdır Province is situated in the Eastern Anatolian Region of Turkey. Wild edible Competing interests plants and their utilization methods have not been previously documented there. No competing interests have been declared. Tis study was conducted during an ethnobotanical survey of Iğdır Province from 2007 to 2012, in the period from May to October, when plants were in their fower- Copyright notice ing and fruiting periods. Tere were 210 interviews carried out in 78 villages. Tis © The Author(s) 2017. This is an study provides information about 154 wild plant taxa belonging to 27 families that Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative have been used as foodstufs, spices, or hot drinks. Seventeen wild edible plants were Commons Attribution License, recorded for the frst time during this study. Eight endemic species were reported which permits redistribution, as used for their edibility, and new local names for plants were also recorded. Te commercial and non- cultural importance index was calculated for each taxon. -

Eriqua and Minuahinili: an Early Iron Age-Nairi Kingdom and Urartian Province on the Northern Slope of Mt Ağri (Settlement Complexes at Melekli and Karakoyunlu)

TÜBA-AR 21/2017 ERIQUA AND MINUAHINILI: AN EARLY IRON AGE-NAIRI KINGDOM AND URARTIAN PROVINCE ON THE NORTHERN SLOPE OF MT AĞRI (SETTLEMENT COMPLEXES AT MELEKLI AND KARAKOYUNLU) ERİQUA VE MİNUAHİNİLİ: AĞRI DAĞI’NIN KUZEY ETEĞİNDE BİR ERKEN DEMİR ÇAĞ-NAİRİ KRALLIĞI VE URARTU EYALETİ (MELEKLİ VE KARAKOYUNLU YERLEŞİM KOMPLEKSLERİ) Makale Bilgisi Article Info Başvuru: 11 Ekim 2017 Received: October 11, 2017 Hakem Değerlendirmesi: 23 Ekim 2017 Peer Review: October 23, 2017 Kabul: 4 Aralık 2017 Accepted: December 4, 2017 DOI Numarası: 10.22520/tubaar.2017.21.004 DOI Number: 10.22520/tubaar.2017.21.004 Aynur ÖZFIRAT *1 Keywords: Mt Ağrı, Minuahinili, Eriqua, Nairi, Late Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, Urartu, Eastern Anatolia, Southern Transcaucasia, Northwestern Iran Anahtar Kelimeler: Ağrı Dağı, Minuahinili, Eriqua, Nairi, Son Tunç Çağ, Erken Demir Çağ, Urartu, Doğu Anadolu, Güney Kafkasya, Kuzeybatı İran ABSTRACT Highland of eastern Anatolia, southern Transcaucasia and northwestern Iran were divided among a great number of local polities in the Late Bronze-Early Iron Age (c. 1600-900 BC). By the change of political power, regional landscape previously consisted of small local polities largely transformed into a province of the kingdom of Urartu (Middle Iron Age, c. 900-600 BC). The Urartian conquest of the Araxes valley-Mt Ağrı region began the earlier stage of the kingdom. Some of the sites that we investigated in the region show a developed and complex system. These settlement complexes were located in central area of geographical units. Each of the them covers interrelated units in a vast * Prof. Dr., Mardin Artuklu Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Arkeoloji Bölümü, Kampüs Yerleşkesi, Diyarbakır Yolu 5. -

IĞDIR TOURISM DISCOVERY GUIDE and TREKKING ROUTES

IĞDIR TOURISM DISCOVERY GUIDE and TREKKING ROUTES NOVEMBER 2013 1 PUBLISHED BY SERHAT KALKINMA AJANSI www.serka.gov.tr [email protected] Tel : 0474 212 52 00 Faks : 0474 212 52 04 PREPARED BY Ersin DEMİREL [email protected] www.ersindemirel.blogspot.com CONTRIBUTIONS Uğur ÇALIŞKAN, PhD Osman ENGİNDENİZ (Iğdır Provincial Culture and Tourism Deputy Director ) Ass. Prof. Dr. Yıldırım GÜNGÖR Mete TÜRKOĞLU (Iğdır Forestry and Water Affairs Provincial Directorate) Doç. Dr. YUSİF ZEYNALOV (Iğdır University Faculty of Agriculture) KuzeyDoğa Association PHOTOGRAPHY Ersin DEMİREL Mukadder YARDIMCIEL Iğdır Forestry and Water Affairs Provincial Directorate KuzeyDoğa Association GRAPHIC DESIGN Ali GÖÇMEN [email protected] First Print in English November 2013 All rights reserved. Content and visuals in the guide cannot be reprinted or reproduced fully or in part without permission of the copyright holder. 2 CONTENTS Preface 4 About Iğdır 6 Ağrı Mountain and National Park 12 History 14 Iğdır Discovery Route 20 Flora and Fauna 28 About Trekking Routes 36 Warnings and Precautions For Trekkers 38 Iğdır Trekking Routes 40 Where is it? 106 What to Buy? 108 Transportation 114 Lodging 116 Important Phones 117 Information and Local Guidance 118 Bibliography 118 3 PREFACE World is going through arguably the fastest and most dazzling economic and social transformations. Developments in science and technology have brought countries together and paved the way for fast distribution and use of knowledge. Local devel- opment approach is one of the most efficient methods developed in the near past for nationally and internationally competitive, innovative and sustainable develop- ment. Regional Development agencies operate in many countries within this perspective. -

Ras 38 Layout 1

RESEARCH ARTICLE / ARAŞTIRMA MAKALESİ To cite this article: Cankorel, Ali Bilge. “Contributions of the Turkish Eastern Army Under General Kazım Karabekir’s Command to Turkish National Resistance and Peace-Making with the Caucasian Republics at World War-I and the Following Turkish War of Liberation.” Review of Armenian Studies, Issue 38 (2018): 65-115. Received: 05.09.2018 Accepted: 29.10.2018 CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE TURKISH EASTERN ARMY UNDER GENERAL KAZIM KARABEKİR’S COMMAND TO TURKISH NATIONAL RESISTANCE AND PEACE-MAKING WITH THE CAUCASIAN REPUBLICS AT WORLD WAR-I AND THE FOLLOWING TURKISH WAR OF LIBERATION* (BİRİNCİ DÜNYA VE KURTULUŞ SAVAŞLARINDA KAZIM KARABEKİR KOMUTASINDAKİ TÜRK ORDUSUNUN MİLLÎ MÜCADELEYE VE KAFKAS CUMHURİYETLERİYLE BARIŞIN TESİSİNE KATKILARI) Ali Bilge CANKOREL** Abstract: World War-I was considerably about the territorial partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The Allied powers of Great Britain and France had offered, apart from their own shares, Istanbul, Turkish Straits of the Dardanelles and Bosphorus, parts of the eastern Black Sea coast-line and of Eastern Anatolia to Russia, while promising Greece the Aegean coast including İzmir (Smyrnia), also planning the establishment of carved-out Armenian and Greek-Pontus states. The Mudros Armistice Treaty of 30 October 1918 and the Sèvres Peace Treaty of 10 August 1920 officialised these * This is the English translation by Ahmet Can Öktem of the article authored by Ali Bilge Cankorel titled “Birinci Dünya Savaşı ve Millî Mücadelede Kâzım Karabekir Komutasındaki Türk Ordusunun Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Doğu Sınırlarının Çizilmesi ve Kafkas Cumhuriyetleriyle Barışın Tesisi Yolunda Katkıları” that was originally published in the Ermeni Araştırmaları journal. To view the original article: Ali Bilge Cankorel, “Birinci Dünya Savaşı ve Millî Mücadelede Kâzım Karabekir Komutasındaki Türk Ordusunun Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Doğu Sınırlarının Çizilmesi ve Kafkas Cumhuriyetleriyle Barışın Tesisi Yolunda Katkıları,” Ermeni Araştırmaları, Sayı 60 (2018): 25-72. -

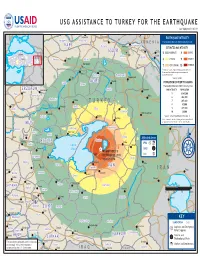

USAID/OFDA Turkey Program Map 11/2/2011

USG ASSISTANCE TO TURKEY FOR THE EARTHQUAKE Last Updated 11/02/11 b MerkezMerkez Kagizman b EARTHQUAKE INTENSITYMartuni HorasanHorasan SarikamisSarikamis KagizmanKagizman Tuzluca b The Modified Mercalli (MMI) Intensity Scale* Pasinler Horasan ARMENIA KARSK A R S TuzlucaTuzluca Karakoyunlu KarakoyunluKarakoyunlu Koprukoy ESTIMATED MMI INTENSITY PasinlerPasinler Aralik Vedi IGDIRI G D I R !P MODERATE SEVERE Ankara 5 8 ! KoprukoyKoprukoy MerkezMerkez Igdir Ararat Erzurum AralikAralik TURKEY EleskirtEleskirt Eleskirt MerkezMerkez 6 STRONG 9 VIOLENT Karakose Mount Ararat EXTREME Karayazi b!P # 7 VERY STRONG 10 Tekman *MMISadarak is a measure of ground shaking and is different Taslicay from overall earthquake magnitude as measuredAjabaj Hamur TaslicayTaslicay DogubeyazitDogubeyazit by the Richter Scale. TekmanTekman KarayaziKarayazi Tutak Dogubayazit BasSource: Amirxanli USGS AGRIA G R I Diyadin b POPULATIONSarur EXPOSED TO SHAKING TutakTutak HamurHamur The Modified Mercalli (MMI) Intensity Scale ERZURUME R Z U R U M Karacoban DiyadinDiyadin Bazargan MMI INTENSITY POPULATION Hinis HinisHinis 5 9,345,000 KaracobanKaracoban Maku AZERBAIJAN 6 482,000 MalazgirtMalazgirt Patnos TURKEY 7 265,000 Varto Murat Nehri 8 67,000!P Malazgirt PatnosPatnos Caldiran b VartoVarto ErcisErcis 9 377,000 Babak CaldiranCaldiran 10 29,000b Bulanik Siah Cheshmeh Ercis Source: USGS/PAGER Alert Version: 2 BulanikBulanik Muradiye Note: Estimated extents of shaking intensity and affected MUSM U S populations do not reflect the effects of aftershocks. MuradiyeMuradiye -

Aesthetics of Displacement Topics and Issues in National Cinema Volume 4 Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and Its Minorities on Screen

Aesthetics of Displacement Topics and Issues in National Cinema volume 4 Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen Series Editor: Armida de la Garza, University College Cork, Ireland Editorial Board: Mette Hjort, Chair Professor and Head, Visual Studies Lingnan University, Hong Kong Lúcia Nagib, Professor of Film, University of Reading, UK Chris Berry, Professor of Film Studies, Kings College London, UK, and Co-Director of the Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre, UK Sarah Street, Professor of Film and Foundation Chair of Drama, University of Bristol, UK Jeanette Hoorn, Professor of Visual Cultures, University of Melbourne, Australia Shohini Chaudhuri, Senior Lecturer and MA Director in Film Studies, University of Essex, UK Other volumes in the series: Volume 1: Revolution and Rebellion in Mexican Film by Niamh Th ornton Volume 2: Ecology and Contemporary Nordic Cinemas: From Nation-Building to Ecocosmopolitanism by Pietari Kääpä Volume 3: Cypriot Cinemas edited by Costas Constandinides and Yiannis Papadakis Volume 4: Aesthetics of Displacement by Özlem Köksal Volume 5: Film Music in ‘Minor’ National Cinemas edited by Germán Gil-Curiel Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen Özlem Köksal Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc 1385 Broadway 50 Bedford Square New York London NY 10018 WC1B 3DP USA UK www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2016 Paperback edition fi rst published 2017 © Özlem Köksal, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. -

KARS TOURISM EXPEDITION GUIDE June 2013

KARS TOURISM EXPEDITION GUIDE June 2013 1 PUBLISHED BY: SERHAT DEVELOPMENT AGENCY www.serka.gov.tr PHONE: 0090 474 212 52 00 Fax: 0090 474 212 52 04 EDITED BY: Ersin DEMİREL [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS: Dr. Hüseyin TUTAR, Dr. Uğur ÇALIŞKAN, İlhan KOÇULU, Sezai YAZICI, Vedat AKÇAYÖZ, North Nature Society PHOTOS: Ersin DEMİREL, Mukadder YARDIMCIEL GRAPHIC DESIGN: Ali GÖÇMEN [email protected] June 2013 All publication rights reserved. The writings and visuals within this guide can not be published or copied partly or as a whole without permission of Serhat Develop- ment Agency. ISBN number: 978-605-62728-6-8 2 CONTENTS ABOUT KARS 8 KARS CITY TOUR 10 KARS EXPEDITION ROUTE 22 HISTORY TOUR 32 A TRIP INTO THE PAST 52 A TRIP INTO THE NATURE 56 KÜLTÜR TURLARI 74 TREKKING ACTIVITIES 86 CYCLING ROUTES 92 JEEP SAFARI-SCENIC VEHICLE ROAD 98 KARS-AĞRI CULTURE AND ADVENTURE ROAD 102 KARS-ARDAHAN CULTURE AND NATURE JOURNEY 104 WINTER TOURISM 106 WHAT IS WHERE 108 WHAT TO BUY 110 TRANSPORTATION 114 ACCOMMODATION 116 CAR RENTAL AND IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS 119 INFORMATION AND LOCAL GUIDANCE 120 3 INTRODUCTION The earth is undergoing one of its fastest and most dazzling eras with regard to economical and social changes. Rapid advances in science and technology made the countries more connected and allowed the emerging information to rapidly spread and be utilized. One of the most efficient methods developed recently for innovative and sustainable development is the concept of local development. Within the frame of this new approach, today ‘’Regional Development Agencies’’ operate in several countries. -

The Ottoman Home Front During World War I: Everyday Politics, Society, and Culture

The Ottoman Home Front during World War I: Everyday Politics, Society, and Culture Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yiğit Akın Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway David L. Hoffman Copyright by Yiğit Akın 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to examine the socio-economic and cultural dimensions of the home-front experience of the Ottoman people during World War I. It explores the new realities that the war created in the form of mass conscription, a state-controlled economy, government requisitioning of grain and possessions, widespread shortages, forcible deportations and voluntary displacements, death, and grief. Using archival and non-archival sources, it also focuses on how Ottomans wrestled with these wartime realities. World War I required the most comprehensive mobilization of men and resources in the history of the Ottoman Empire. In order to wage a war of unprecedented scope effectively, the Ottoman government assumed new powers, undertook new responsibilities, and expanded its authority in many areas. Civilian and military authorities constantly experimented with new policies in order to meet the endless needs of the war and extended the state’s capacity to intervene in the distant corners of the empire to extract people and resources to a degree not seen before. Victory in the war became increasingly dependent on the successful integration of the armies in the field and the home-front population, a process that inescapably led to the erosion of the distinction between the military and civilian realms.