On Modes of Visual Narration in Early Buddhist Art Author(S): Vidya Dehejia Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paramis a Historical Background by Guy Armstrong

The Paramis A Historical Background by Guy Armstrong The ascetic Sumedha Four incalculables and one hundred thousand eons before our present age – which is to say a very, very, very long time ago – an ascetic named Sumedha was practicing the path to arahantship when he received word that a fully self-awakened one, a Buddha named Dipankara, was teaching in a town nearby. He traveled there and found Dipankara Buddha being venerated in a long procession attended by most of the townspeople. Sumedha was immediately touched with deep reverence upon seeing the noble bearing and vast tranquility of the Buddha. He realized that to become an arahant would be of great benefit to humankind, but that the benefit to the world of a Buddha was immensely greater. At that very moment, in the presence of Dipankara Buddha, he made a vow to become a Buddha in a future life. This marked his entry into the path of the bodhisattva, a being bound for buddhahood. Just then Sumedha noticed that the Buddha was about to walk through a patch of wet mud. Spontaneously, out of great devotion, he threw his body down in the mud and invited the Buddha and his Sangha to walk over him rather than dirty their feet. As the great teacher passed, Dipankara Buddha read Sumedha’s mind, understood his aspiration, and predicted that the ascetic Sumedha would fulfill his vow to become a Buddha at a time four incalculables and a hundred thousand eons in the future. It was also revealed to Sumedha that had he not made the aspiration to become a Buddha, he would have realized full enlightenment that day by listening to a discourse from Dipankara Buddha. -

![[68-02-00-F] Feb., 1968, Lotus Sutra #6 ZMC](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0761/68-02-00-f-feb-1968-lotus-sutra-6-zmc-2720761.webp)

[68-02-00-F] Feb., 1968, Lotus Sutra #6 ZMC

68-02-00.L6 [68-02-00-F] Feb., 1968, Lotus Sutra #6 Z.M.C. (transcription checked, edited by Brian Fikes) "The monks and nuns at the time being, who strove after supreme, highest enlightenment, numerous as sand of the Ganges, applied themselves to the commandment of the Sugata. "And the monk who then was the preacher of the law and the keeper of the law, Varaprabha, expounded for fully eighty intermediate kalpas the highest laws according to the commandment (of the Sugata)." In other words, Buddha's teaching is eternal truth, beginningless and endless. And the Bodhisattva Varaprabha expounded it for fully eighty intermediate kalpas, in other words, for a limitlessly long time. "He had eight hundred pupils, who all of them were by him brought to full development. They saw many kotis of Buddhas, great sages, whom they worshipped." "He had eight hundred pupils." This is different from the prose part, which says: "Now it so happened, Ajita, that the eight sons of the Lord Kandrasuryapradipa, Mati and the rest, were pupils to that very Bodhisattva Varaprabha. They were by him made ripe for supreme, perfect enlightenment, and in after times they saw and worshipped many hundred thousand myriads of kotis of Buddhas, all of whom had attained supreme, perfect enlightenment, the last of them being Dipankara, the Tathagata, the perfectly enlightened one." Gatha 88: "By following the regular course they became Buddhas in several spheres, and as they followed one another in immediate succession they successively foretold each other's future destiny to Buddhaship. "The last of these Buddhas following one another was Dipankara. -

The Diamond Sutra

THE DIAMOND SUTRA THE DIAMOND SUTRA 1 Diamond Sutra The full Sanskrit title of this text is the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (The Vajra Prajna Paramita Sutra). The Buddha said this Sutra may be known as “The Diamond that Cuts through Illusion.” Like many Buddhist sūtras, The Diamond Sūtra begins with the famous phrase, "Thus have I heard." The Buddha finished his daily walk with the monks to gather offerings of food and sits down to rest. The monk Subhūti comes forth and asks the Buddha a question. What follows is a dialogue regarding the nature of perception. The Buddha often uses paradoxical phrases such as, "What is called the highest teaching is not the highest teaching". The Buddha is generally thought to be helping Subhūti unlearn his preconceived, limited notions of the nature of reality and enlightenment. The Diamond Sūtra is a short and well-known Mahāyāna sūtra from the Prajñāpāramitā, or "Perfection of Wisdom" genre, and it emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment. A list of vivid metaphors for impermanence appears in a popular four-line verse at the end of the sūtra: All conditioned phenomena Are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, or shadows; Like drops of dew, or flashes of lightning; Thusly should they be contemplated. A copy of the Chinese version of The Diamond Sūtra, found among the Dunhuang manuscripts in the early 20th century and dating back to May 11, THE DIAMOND SUTRA 868 C.E. is considered the earliest complete survival of a woodblock printing folio. This discovered text was made over 500 years before the Gutenberg 2 printing press in 1450 C.E. -

The Standing Buddha of Guita Bahi Image Pages

asianart.com | articles Appendix 1: The Inscriptions Asianart.com offers pdf versions of some articles for the convenience of our visitors and readers. These files should be printed for personal use only. Note that when you view the pdf on your computer in Adobe reader, the links to main image pages will be active: if clicked, the linked page will open in your browser if you are online. This article can be viewed online at: www.asianart.com/articles/guita/part1 The Standing Buddha of Guita Bahi by Ian Alsop, Kashinath Tamot and Gyanendra Shakya Part I The Standing Buddha of Guita Bahi Further Thoughts on The Antiquity of Nepalese Metalcraft Ian Alsop Image Pages On The Antiquity of Nepalese Metalcraft: The Buddha of Guita Bahi Last Image Back to main article Next Image click on the image to enlarge | click on the image again to enlarge further click Esc or X to close and return to this page Figure 1: Standing Buddha Northeastern India or Nepal, Gupta/Licchavi Period Inscription dated Śaka Samvat 513, 591 CE Bronze Overall: 46.5 x 15.4 x 13.4 cm (18 5/16 x 6 1/16 x 5 1/4 in.); without base: 35 x 13.8 x 10.5 cm (13 3/4 x 5 7/16 x 4 1/8 in.) The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1968.40 All Photos: courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art https://cmaweb23-bbn-2.clevelandart.org/art/1968.40 Details: see thumbnails below 01 - head 02 - right hand 03 - left hand 04 - back 05 - from right side 06 - from left side 07 - detail of back For images and reading of the inscription, visit Appendix 1: The Inscriptions: InscriptionInscription FigFig 1/121/12. -

Dīpankara Buddha - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Īpankara Buddha

דִ יפַּנְקַּרַּ ה ديبانكارا https://www.scribd.com/doc/55142742/16-Daily-Terms ِديپانکارا दीपंकर ِديپَن َک َرَ http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx Dīpankara Buddha - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D īpankara_Buddha Dīpankara Buddha From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Dīpankara (Sanskrit and Pali Dīpa ṃkara , "Lamp bearer"; Bengali: দীপVর ; Chinese 燃燈佛 (pinyin Ránd ēng Fo); Dīpankara Buddha Tibetan མར་མེ་མཛད། mar me mdzad ; Mongolian Jula-yin Jokiya γč i, Dibangkara , Nepal Bhasa: िदपंखा Dīpankha , Vietnamese Nhiên Đă ng Ph ật) one of the Buddhas of the past, said to have lived on Earth one hundred thousand years. Theoretically, the number of Buddhas having existed is enormous and they are often collectively known under the name of "Thousand Buddhas". Each was responsible for a Ascetic Sumedha and Dipankara Buddha life cycle. According to some Buddhist traditions, Sanskrit Dīpa ṃkara Dīpankara (also D īpamkara) was a Buddha who reached enlightenment eons prior to Gautama, the historical Buddha. Pāli Dīpa ṃkara Burmese ဒီပကရာ ([dìp ɪ̀ɴ kəɹ à]) Generally, Buddhists believe that there has been a succession Chinese 燃燈佛 (Ránd ēng Fo) of many Buddhas in the distant past and that many more will appear in the future; D īpankara, then, would be one of Mongolian Z^:? UV% Z a<KWX᠂ OV <7 < ; numerous previous Buddhas, while Gautama was the most Зулын Зохиогч , Дивангар ; recent, and Maitreya will be the next Buddha in the future. Zula yin Zohiyagci, Divangar Chinese Buddhism tends to honor D īpankara as one of many Thai พระทีปังกรพุทธเจ ้า Buddhas of the past. -

Gupta Period

Mahayana Inscriptions in the Gupta Period Masao Shizutani We have some examples of Mahayana sculptures (e. g. Avalokitesvara (1) images) of the Kushana period, but a single Mahayana inscription of the same period has not been found. Among Gupta inscriptions, however, we can find following Mahayana inscriptions. 1. The Gunaighar grant of Vainyagupta: the year 188 (Gupta Era, (2) A. D. 506) This grant records some gifts to "the Avaivarttika , congre- gation of monks (belonging) to the Mahayana" (Mahayanika-avaivarttika- bhiksusagha), established by "the Buddhist monk of Mahayana" (Mahaya- nika-Sakyabhiksu), Santideva, in the Aryya-Avalokitesvara-asrama-vihara. (3) 2. Sarnath Buddhist image inscription (Liiders no. 1441) Written on the base of the standing figure of Bodhisattva Avalokitesv- ara, and in Brahmi script of the 5th century. L.1 Om Deyadharmmoyam paramopasaka-visayapati-suyattrasya. L.2 Yad atra punyam tad bhavatu sarvvasatvanam anuttara jnanava- ptaye. (Translation) Orh ! (This image is) the meritorious gift of the para- mopasaka, the chief of the-district (visayapati) Suyattra. Whatever religious merit (there is) in this (act), let it be for the attainment of supreme know- ledge by all sentient beings. The donor must have been a devotee of Avalokitesvara, and therefore, a follower of Mahayana Buddhism. (4) 3. Mathura Buddhist image inscription (Liiders no. 144) Written on the pedestal of the seated Buddha, headless, arms destro- yed, apparently preaching the Law, and in Brahmi script of the 5th cent- ury. This inscription is said to be partially defaced. L.1 Deyadharmoyam Sam Cghatra) kha (?) kutum [bi] nya Buddhasya -358- (48) Mahayana Inscriptions in the Gupta Period(M. -

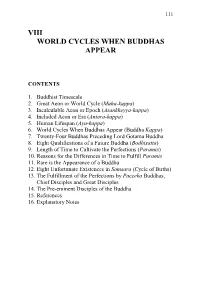

Viii. World Cycles Whe N Buddhas Appear

111 VIII WORLD CYCLES WHE BUDDHAS APPEAR COTETS 1. Buddhist Timescale 2. Great Aeon or World Cycle ( Maha-kappa ) 3. Incalculable Aeon or Epoch ( Asankheyya-kappa ) 4. Included Aeon or Era ( Antara-kappa ) 5. Human Lifespan ( Ayu-kappa ) 6. World Cycles When Buddhas Appear (Buddha Kappa ) 7. Twenty-Four Buddhas Preceding Lord Gotama Buddha 8. Eight Qualifications of a Future Buddha (Bodhisatta ) 9. Length of Time to Cultivate the Perfections ( Paramis ) 10. Reasons for the Differences in Time to Fulfill Paramis 11. Rare is the Appearance of a Buddha 12. Eight Unfortunate Existences in Samsara (Cycle of Births) 13. The Fulfillment of the Perfections by Pacceka Buddhas, Chief Disciples and Great Disciples 14. The Pre-eminent Disciples of the Buddha 15. References 16. Explanatory Notes 112 • Buddhism Course 1. Buddhist Timescale In the Buddhist system of timescale, the word “ kappa ” meaning “cycle or aeon” is used to denote certain time-periods that repeat themselves in cyclical order . Four time-cycles are distinguished; a great aeon ( maha-kappa ), an incalculable aeon ( asankheyya-kappa ), an included aeon ( antara-kappa ) and a lifespan ( ayu-kappa ). 2. Great Aeon or World Cycle (Maha-kappa ) A maha kappa or aeon is generally taken to mean a world cycle . How long is a world cycle? In Samyutta ii, Chapter XV, the Buddha used the parables of the hill and mustard-seed for comparison: • Suppose there was a solid mass, of rock or hill, one yojana (eight miles) wide, one yojana across and one yojana high and every hundred years, a man was to stroke it once with a piece of silk. -

Diving Deeper Into Buddhism: Mapping the Buddhist Cosmos

lesson plan Diving Deeper into Buddhism: Mapping the Buddhist Cosmos Subjects: Social Studies Grade Level: Middle School/Junior High, High School Duration: 90 minutes Dynasty: Period of Division (220–589) Object Type: Sculpture, Stone Themes: Language and Stories; Animals and Nature; Traditions and Belief Systems; Technology and Production Contributed by: Lesley Younge, Middle School Teacher, Whittle School and Studios, Washington, DC Buddha draped in robes portraying the Realms of Existence China Northern Qi dynasty, 550–577 Limestone 59 9/16 x 24 3/4 x 12 5/16 in Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment. Freer Gallery of Art, F1923.15 Objective Students already familiar with Siddhartha Gautama, or Shakyamuni, the Historical Buddha, will deepen their understanding of Buddhist beliefs and artwork. They will analyze and interpret works of art that reveal how people live around the world and what they value. They will identify how works of art reflect times, places, cultures, and beliefs. Essential Questions • What other stories are told in Buddhism beyond Shakyamuni, the Historical Buddha? • How were Buddhist beliefs transmitted between teachers and students? • How do works of art capture and communicate the development of Buddhist beliefs in China? • How has art inspired Buddhist believers and scholars throughout history? • Why did Buddhists create a symbolic map of the world, or cosmology? Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art Arthur M. Sackler Gallery lesson plan: Diving Deeper into Buddhism: Mapping the Buddhist Cosmos 1 Background Information This limestone sculpture started its life in China during the Northern Qi dynasty (550–77), most likely carved by a team of craftsmen. From that point forward, little is known about the Cosmic Buddha’s history until it appeared on the art market in Beijing more than a millennium later in 1923. -

Buddhist Imagery

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 6 1-1-1972 Buddhist Imagery Richard Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Edwards, Richard (1972) "Buddhist Imagery," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol12/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Edwards: Buddhist Imagery buddhist imagery RICHARD EDWARDS As with the founders of other major world religions so far as we know no buddhist disciple ever sat down during the lifetime of the teacher and produced a likeness of sid- dartha gautama as the historical buddha was called thus in proposing to discuss buddhist imagery there is no possi- bility of describing in the sense of portraiture what he and his followers looked like all this to follow out buddhist notions of escape from attachment to the phenomenal world has long since passed into nirvana if the light of attachment has gone out then there is no longer anything to see it is well known that india the land of the origin of buddhism was long reluctant to change this concept carvings associated from the last part of the second and into the first century BC designate only what happens when the presence of the buddha is known there is joy there is -

High King Avalokitesvara Sutra

High King Avalokitesvara Sutra Namo Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, na mo guan shi yin pu sa, Namo Buddhaya, na mo fo, Namo Dharmaya, na mo fa, Namo Sanghaya, na mo seng, An affinity with the Pure Lands opens the Dharma Doors. fo guo you yuan, fo fa xiang yin, By engaging permanence, bliss, identity, and purity, one is blessed with the Dharma. chang le wo jing, you yuan fo fa. Namo Maha Prajna Paramita, a great spiritual mantra. na mo mo he bo re bo luo mi shi da shen zhou. Namo Maha Prajna Paramita, a great wisdom mantra. na mo mo he bo re bo luo mi shi da ming zhou. Namo Maha Prajna Paramita, a supreme mantra. na mo mo he bo re bo luo mi shi wu shang zhou. Namo Maha Prajna Paramita, an unequaled mantra. na mo mo he bo re bo luo mi shi wu deng deng zhou. 1 Namo Suddharasmiprabhaguhya Buddha, na mo jing guang mi mi fo, Dharmakara Buddha, fa zang fo, Simhanada Rddhividhijnanaraja Buddha shi zi hou shen zu you wang fo, Merupradiparaja Buddha, fo gao xu mi deng wang fo, Dharmapala Buddha, fa hu fo, Vajragarbha - simhakridanika Buddha, jin gang zang shi zi you xi fo, Ratna vijaya Buddha, bao sheng fo, Rddhiabhijnana Buddha, shen tong fo, Bhaisajyaguru Vaiduryaprabharaja Buddha yao shi liu li guang wang fo, Samantaprabha gunagiriraja Buddha, pu guang gong de shan wang fo, 2 Supratisthita gunaratnaraja Buddha shan zhu gong de bao wang fo, Sapta Atita Buddha, guo qu qi fo, Anagata Bhadrakalpa Sahasra Buddha wei lai xian jie qian fo, the Fifteen Hundred Buddhas, qian wu bai fo, the Fifteen Thousand Buddhas, wan wu qian fo, the Five Hundred Padmasriraja Buddhas, wu bai hua sheng fo, the Ten Billion Vajragarbha Buddhas, bai yi jin gang zang fo, Dipankara Buddha. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal of Theravāda, by Shanta Ratnayaka

The Bodhisattva Ideal of Theravāda, by Shanta Ratnayaka The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Vol. 8, No. 2 1985 The Bodhisattva Ideal of Theravada* by Shanta Ratnayaka Many detailed accounts of the bodhisattva (Pali: bodhisatta) ideal of the Mahayana have been published by students of Buddhism. Most of these writers are so fascinated with the b.lahay2na model of the bodhisattva ideal that they pay no atten- tion to the Theravada teaching on this point. Sometimes they contrast bodhisattvas with arahants (arhat or arahat) and se- verely criticize the latter. Such a criticism is possible, from my point of view, only if the critic is either biased towards the Mahayana tradition, or has misinterpreted the Theravada, or has misunderstood Buddhism altogether. In this article, I will present the Theravada concept of the bodhisattva ideal, and then try to correct some misunderstand- ings on the issue and show the unfairness of certain criticisms that have been directed towards the Theravada position. Part I of this paper distinguishes the Theravada from the Hinayana, Part I1 examines the bodhisattva ideal in the Theravada texts, Part 111 observes the actual practice of the ideal among the Theravadins, and Part IV clarifies bodhisattvahood and arahant- hood and places them in relation to the Buddhahood and bodhi (enlightenment).Through this exposition most of the criticisms that are based on misunderstandings will be swept away. My further reflections will form Part V, the Conclusion, of this essay. I. TheravGda Cannot be Hinayana The Cullavagga records that soon after the Buddha's demise his Elderly Disciples (Theras) met at R2jagaha (Rajagrha) to form the First Council.' Headed by MahakaSyapa, ~nanda,and 86 JIABS VOL. -

86 on Making Venerative Offerings to Buddhas (Kuyō Shobutsu)

86 On Making Venerative Offerings to Buddhas (Kuyō Shobutsu) Translator’s Introduction: The key term in this discourse is kuyō, translated in the title as ‘making venerative offerings’, and shortened in the text itself to ‘making offerings’ or some variation thereof. It refers not only to selflessly giving alms and expressing gratitude to the Buddhas but also to showing respect for the sacred objects associated with Them, such as the memorial monuments called stupas, which also serve as reliquaries for sacred relics. What is important is the attitude of mind behind the offering, and, when it is free of any tinge of self, the merit that returns to the giver thereby is, as Dōgen says, beyond measure. The original text, which is still in draft stage, is one of twelve that Dōgen had not been able to complete before his death. It contains many excerpts, particularly from writings attributed to Nāgārjuna. The Buddha once said the following in verse: If there were no past ages, There could not have been Buddhas in the past. If there were no Buddhas in the past, There could be no leaving home to accept the full Precepts. Clearly you need to keep in mind that Buddhas invariably exist in the three temporal worlds. When it comes to the Buddhas of the past, do not assert that They had a beginning, and do not assert that They had no beginning. If you erroneously impose upon Them Their having or not having a beginning and an end, this is not something that you have learned from the Buddha’s Teaching.