Hyoscine) for Preventing and Treating Motion Sickness (Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Antiemetics/Antivertigo Agents

Antiemetic Agents Therapeutic Class Review (TCR) May 1, 2019 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage or retrieval system without the express written consent of Magellan Rx Management. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Magellan Rx Management Attention: Legal Department 6950 Columbia Gateway Drive Columbia, Maryland 21046 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Send comments and suggestions to [email protected]. May 2019 Proprietary Information. Restricted Access – Do not disseminate or copy without approval. © 2004-2019 Magellan Rx Management. All Rights Reserved. 3 FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS Drug Manufacturer Indication(s) NK1 receptor antagonists aprepitant capsules generic, Merck In combination with other antiemetic agents for: (Emend®)1 . -

Scopolamine As a Potential Treatment Option in Major Depressive Disorder - a Literature Review

Isr J Psychiatry - Vol. 58 - No 1 (2021) Scopolamine as a Potential Treatment Option in Major Depressive Disorder - A Literature Review Dusan Kolar, MD, MSc, PhD, FRCPC Department of Psychiatry, Queen’s University, Mood Disorders Research and Treatment Service, Kingston, Ontario, Canada as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and ABSTRACT serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), are currently used as first-line pharmacological treat- Introduction: Slow onset response to antidepressants ments for major depressive disorder (MDD). Despite the and partial response is a common problem in mood availability of a comprehensive list of antidepressants, disorders psychiatry. There is an ongoing need for rapid- approximately 50% of the patients on an antidepressant acting antidepressants, particularly after introducing regimen experience non-response to treatment (3, 4). ketamine in the treatment of depression. Scopolamine Furthermore, the mood elevating effects of antidepres- may have promise as an antidepressant. sant medication is often delayed (5). It is recommended Methods: The author conducted a literature review to that the patient be treated for at least six weeks with identify available treatment trials of scopolamine in the adequate dosage of the given antidepressant before unipolar and bipolar depression in PubMed, the Cochrane considering making changes to the treatment (5). Partial database, Ovid Medline and Google Scholar. to no response to treatment with antidepressants and delayed onset of action indicate that there is a need for Results: There have been eight treatment trials of the development of novel and improved medications scopolamine in MDD and bipolar depression. Seven for the treatment of depression. Many studies in recent studies confirmed significant antidepressant effects years have recognised two different classes of drugs with of scopolamine used as monotherapy and as an rapid and robust antidepressant effects. -

The Promise of Ketamine

Neuropsychopharmacology (2015) 40, 257–258 & 2015 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/15 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Editorial Circumspectives: The Promise of Ketamine William A Carlezon*,1 and Tony P George2 1 2 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Neuropsychopharmacology (2015) 40, 257–258; doi:10.1038/npp.2014.270 In this issue we reprise a Feature called Circumspectives. offering hope that fast-acting but safe antidepressants are The general format of a Circumspectives article is similar to possible. a debate, with separate sections in which two thought Despite growing enthusiasm for ketamine and its leaders articulate their individual positions on a topic of promise, Dr Schatzberg describes some sobering details great importance to our community of researchers. The and gaps in knowledge. Ketamine is a drug of abuse and, distinguishing element, however, is that the piece ends with despite some exceptionally elegant studies on the mechan- a ‘reconciliation’ that is co-authored by both and includes ism (eg, Li et al, 2010; Autry et al, 2011), there is no ideas or experiments that will move the field forward. consensus on how it produces therapeutic effects. As one The current Circumspectives (Sanacora and Schatzberg, example, Dr Schatzberg points out similarities in some of 2015) is entitled ‘Ketamine: Promising Path or False the molecular actions of ketamine and scopolamine, Prophecy in the Development of Novel Therapeutics for another familiar and long-standing member of our phama- Mood Disorders?’. It is co-authored by Gerard Sanacora and copea shown to produce rapid antidepressant effects (Furey Alan F Schatzberg, who are leaders in this field. -

The Anticholinergic Toxidrome

Poison HOTLINE Partnership between Iowa Health System and University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics July 2011 The Anticholinergic Toxidrome A toxidrome is a group of symptoms associated with poisoning by a particular class of agents. One example is the opiate toxidrome, the triad of CNS depression, respiratory depression, and pinpoint pupils, and which usually responds to naloxone. The anticholinergic toxidrome is most frequently associated with overdoses of diphenhydramine, a very common OTC medication. However, many drugs and plants can produce the anticholinergic toxidrome. A partial list includes: tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline), older antihistamines (chlorpheniramine), Did you know …… phenothiazines (promethazine) and plants containing the anticholinergic alkaloids atropine, hyoscyamine and scopolamine (Jimson Weed). Each summer, the ISPCC receives approximately 10-20 The mnemonic used to help remember the symptoms and signs of this snake bite calls, some being toxidrome are derived from the Alice in Wonderland story: from poisonous snakes (both Blind as a Bat (mydriasis and inability to focus on near objects) local and exotic). Red as a Beet (flushed skin color) Four poisonous snakes can be Hot as Hades (elevated temperature) found in Iowa: the prairie These patients can sometimes die of agitation-induced hyperthermia. rattlesnake, the massasauga, Dry as a Bone (dry mouth and dry skin) the copperhead, and the Mad as a Hatter (hallucinations and delirium) timber rattlesnake. Each Bowel and bladder lose their tone (urinary retention and constipation) snake has specific territories Heart races on alone (tachycardia) within the state. ISPCC A patient who has ingested only an anticholinergic substance and is not specialists have access to tachycardic argues against a serious anticholinergic overdose. -

Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com

Hallucinogens And Dissociative Drug Use And Addiction Introduction Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that cause alterations in perception, thought, or mood. This heterogeneous group has compounds with different chemical structures, different mechanisms of action, and different adverse effects. Despite their description, most hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. The drugs are more likely to cause changes in mood or in thought than actual hallucinations. Hallucinogenic substances that form naturally have been used worldwide for millennia to induce altered states for religious or spiritual purposes. While these practices still exist, the more common use of hallucinogens today involves the recreational use of synthetic hallucinogens. Hallucinogen And Dissociative Drug Toxicity Hallucinogens comprise a collection of compounds that are used to induce hallucinations or alterations of consciousness. Hallucinogens are drugs that cause alteration of visual, auditory, or tactile perceptions; they are also referred to as a class of drugs that cause alteration of thought and emotion. Hallucinogens disrupt a person’s ability to think and communicate effectively. Hallucinations are defined as false sensations that have no basis in reality: The sensory experience is not actually there. The term “hallucinogen” is slightly misleading because hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com How hallucinogens cause alterations in a person’s sensory experience is not entirely understood. Hallucinogens work, at least in part, by disrupting communication between neurotransmitter systems throughout the body including those that regulate sleep, hunger, sexual behavior and muscle control. Patients under the influence of hallucinogens may show a wide range of unusual and often sudden, volatile behaviors with the potential to rapidly fluctuate from a relaxed, euphoric state to one of extreme agitation and aggression. -

Hyoscyamine, Atropine, Scopolamine, and Phenobarbital

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Hyoscyamine, Atropine, Scopolamine, and Phenobarbital This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. Brand Names: US Donnatal; Phenohytro What is this drug used for? It is used to treat irritable bowel syndrome. It is used to treat ulcer disease. It may be given to your child for other reasons. Talk with the doctor. What do I need to tell the doctor BEFORE my child takes this drug? If your child is allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell the doctor about the allergy and what signs your child had. If your child has any of these health problems: Heart problems due to bleeding, bowel block, enlarged colon, glaucoma, a hernia Hyoscyamine, Atropine, Scopolamine, and Phenobarbital 1/9 that involves your stomach (hiatal hernia), myasthenia gravis, slow-moving GI (gastrointestinal) tract, trouble passing urine, or ulcerative colitis. If your child has ever had porphyria. If your child has been restless or overexcited in the past after taking phenobarbital. If your child is addicted to drugs or alcohol, or has been in the past. This is not a list of all drugs or health problems that interact with this drug. Tell the doctor and pharmacist about all of your child’s drugs (prescription or OTC, natural products, vitamins) and health problems. You must check to make sure that it is safe to give this drug with all of your child’s other drugs and health problems. -

(+)-Hyoscyamine and (–)-Scopolamine

CALL FOR DATA ON (–)-HYOSCYAMINE, (+)-HYOSCYAMINE AND (–)-SCOPOLAMINE Deadline: 31 January 2020 Background Atropine and scopolamine belong to the class of tropane alkaloids (TA), a group of compounds that are secondary metabolites occurring in several plant families, such as Brassicaceae, Solanaceae and Erythroxylaceae. While there are more than 200 different TA identified in various plants, this call for data focuses on (–)-hyoscyamine, (+)-hyoscyamine and (–)-scopolamine. The racemic mixture of (–)-hyoscyamine and (+)-hyoscyamine is called atropine. Tropane Alkaloid related incident Assisting 86.7 million people in around 83 countries each year, the World Food Programme (WFP) is the leading humanitarian organization saving lives and changing lives, delivering food assistance in emergencies and working with communities to improve nutrition and build resilience. Super Cereal is a flour-type product made of pre-cooked corn, soybean and micronutrients. It is used mainly for pregnant and lactating mothers (PLW), nutritionally vulnerable groups including people living with HIV and tuberculosis (TB), and children above five years old. Annually, WFP distributes approximately 130,000 MT Super Cereal to 4.9 million people with the objective of improving food security and preventing malnutrition. In March 2019, four people died and 296 were admitted to health facilities after eating Super Cereal in Uganda. A joint investigation performed by Uganda Government, US CDC/FDA, WHO and WFP pointed towards tropane alkaloids, contaminants issued from toxic seeds (i.e. Datura stramonium), as the cause of intoxication. WFP took immediate measures on the stock and the implicated supplier, and continue to actively consult with experts, including FAO’s Office of Food Safety to manage this risk. -

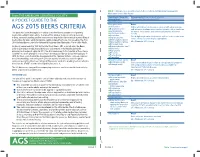

Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults

TABLE 1. 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults From THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY Organ System, Therapeutic Recommendation, Rationale, Quality of Evidence Category, Drug(s) (QE), Strength of Recommendation (SR) A POCKET GUIDE TO THE Anticholinergics First-generation Avoid antihistamines: Highly anticholinergic; clearance reduced with advanced age, AGS 2015 BEERS CRITERIA ■ Brompheniramine and tolerance develops when used as hypnotic; risk of confusion, ■ Carbinoxamine This guide has been developed as a tool to assist healthcare providers in improving dry mouth, constipation, and other anticholinergic effects or ■ Chlorpheniramine toxicity medication safety in older adults. The role of this guide is to inform clinical decision- ■ Clemastine Use of diphenhydramine in situations such as acute treatment of ■ making, research, training, quality measures and regulations concerning the prescribing of Cyproheptadine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate medications for older adults to improve safety and quality of care. It is based on The AGS ■ Dexbrompheniramine QE = Moderate; SR = Strong 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. ■ Dexchlorpheniramine ■ Dimenhydrinate Originally conceived of in 1991 by the late Mark Beers, MD, a geriatrician, the Beers ■ Diphenhydramine (oral) Criteria catalogues medications that cause side effects in the elderly due to the ■ Doxylamine physiologic changes of aging. In 2011, the AGS -

Antiemetics/Antivertigo Agents

Antivertigo Agents Therapeutic Class Review (TCR) February 16, 2018 Please Note: This clinical document has been retired. It can be used as a historical reference. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage or retrieval system without the express written consent of Magellan Rx Management. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Magellan Rx Management Attention: Legal Department 6950 Columbia Gateway Drive Columbia, Maryland 21046 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Send comments and suggestions to [email protected]. February 2018 Proprietary Information. Restricted Access – Do not disseminate or copy without approval. © 2004-2018 Magellan Rx Management. -

Centrally Acting Incapacitants

J R Army Med Corps 2002; 149: 388-391 J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-148-04-09 on 1 December 2002. Downloaded from Centrally Acting Incapacitants GENERAL CNS Stimulants CNS stimulants cause excessive neuronal Introduction activity by facilitating neurotransmission. An incapacitant is a chemical agent which The effect is to overload the cortex and produces a disabling condition that persists other higher regulatory centres making for hours to days after exposure to the agent concentration difficult, causing indecisive- (unlike that produced by riot control agents). ness and inability to act in a sustained Medical treatment will facilitate more rapid purposeful manner. A well known drug recovery, but may not be essential in some which acts in this way is D-lysergic acid cases. Specifically, the term has come to diethylamide (LSD); similar effects are mean those agents that are: sometimes produced by large doses of amphetamines. - highly potent (an extremely low dose is effective) and logistically feasible. Detection - able to produce their effects by altering the In general, no automated stand-off point higher regulatory activity of the CNS. detector systems exist for agents in this - of a duration of action lasting hours or category and only limited field laboratory days, rather than of a momentary or methods exist for the identification of such fleeting action. agents in environmental samples. Initial - not seriously dangerous to life except at diagnosis rests almost entirely upon clinical doses many times the effective dose. acumen, combined with whatever field - not likely to produce permanent injury in intelligence may be available. -

Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology of Datura Species—A Review

antioxidants Review Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology of Datura Species—A Review Meenakshi Sharma 1, Inderpreet Dhaliwal 2, Kusum Rana 3 , Anil Kumar Delta 1 and Prashant Kaushik 4,5,* 1 Department of Chemistry, Ranchi University, Ranchi 834001, India; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.K.D.) 2 Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana 141004, India; [email protected] 3 Department of Biotechnology, Panjab University, Sector 25, Chandigarh 160014, India; [email protected] 4 Kikugawa Research Station, Yokohama Ueki, 2265 Kamo, Kikugawa City 439-0031, Japan 5 Instituto de Conservación y Mejora de la Agrodiversidad Valenciana, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract: Datura, a genus of medicinal herb from the Solanaceae family, is credited with toxic as well as medicinal properties. The different plant parts of Datura sp., mainly D. stramonium L., commonly known as Datura or Jimson Weed, exhibit potent analgesic, antiviral, anti-diarrheal, and anti-inflammatory activities, owing to the wide range of bioactive constituents. With these pharmacological activities, D. stramonium is potentially used to treat numerous human diseases, including ulcers, inflammation, wounds, rheumatism, gout, bruises and swellings, sciatica, fever, toothache, asthma, and bronchitis. The primary phytochemicals investigation on plant extract of Citation: Sharma, M.; Dhaliwal, I.; Datura showed alkaloids, carbohydrates, cardiac glycosides, tannins, flavonoids, amino acids, and Rana, K.; Delta, A.K.; Kaushik, P. phenolic compounds. It also contains toxic tropane alkaloids, including atropine, scopolamine, and Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and hyoscamine. Although some studies on D. stramonium have reported potential pharmacological Toxicology of Datura Species—A effects, information about the toxicity remains almost uncertain.