Beach Recharge in Sussex & East Kent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement to Agenda Agenda Supplement for Cabinet, 04/10

Public Document Pack JOHN WARD East Pallant House Head of Finance and Governance Services 1 East Pallant Chichester Contact: Graham Thrussell on 01243 534653 West Sussex Email: [email protected] PO19 1TY Tel: 01243 785166 www.chichester.gov.uk A meeting of Cabinet will be held in Committee Room 1 at East Pallant House Chichester on Tuesday 4 October 2016 at 09:30 MEMBERS: Mr A Dignum (Chairman), Mrs E Lintill (Vice-Chairman), Mr R Barrow, Mr B Finch, Mrs P Hardwick, Mrs G Keegan and Mrs S Taylor SUPPLEMENT TO THE AGENDA 9 Review of Character Appraisal and Management Proposals for Selsey Conservations Area and Implementation of Associated Recommendations Including Designation of a New Conservation Area in East Selsey to be Named Old Selsey (pages 1 to 12) In section 14 of the report for this agenda item lists three background papers: (1) Former Executive Board Report on Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work - 8 September 2009 (in the public domain). (2) Representation form Selsey Town Council asking Chichester District Council to de-designate the Selsey conservation area (3) Selsey Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Proposals January 2007 (in the public domain). These papers are available to view as follows: (1) is attached herewith (2) has been published as part of the agenda papers for this meeting (3) is available on Chichester District Council’s website via this link: http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5298&p=0 http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5299&p=0 Agenda Item 9 Agenda Item no: 8 Chichester District Council Executive Board Tuesday 8th September 2009 Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work 1. -

Newsletterspring | 2015

Nursing care at home for local children with life-threatening or SPRING | 2015 Newsletter terminal illnesses and support for their families Trekking the Te Araroa Trail for Snowdrop As I write this I'm sitting in the kitchen Whenever I tell other hikers or people So why spend the best part of six of a campsite in Twizel, a small town here who are familiar with the Te Araroa months putting myself through this? near the centre of the South Island in that this is my first ever hike it always Well, despite the difficulties I've pretty New Zealand. Yesterday fellow hiker illicits the same response - which much loved almost every minute of it. Rob and myself walked 40 kilometres is to look at me like I'm crazy. It's However, my main motivation, since the an incredibly physical and mentally early stages of planning this adventure (25 miles) in the hot sun around Lake demanding trail has been to raise Pukaki with its glorious sky-blue water and is, without money for The reflecting the majestic snow covered doubt, the hardest Quinn was a lively little Sussex Snowdrop peak of Mount Cook, the highest challenge I've ever “ Trust. mountain in New Zealand. I've been undertaken. I've guy who loved to kick It is almost 5 years suffered many walking the Te Araroa now for almost a football around, he ago since my blisters, aching four and a half months and the stunning nephew, Quinn feet, back pain, enjoyed watching ‘Antz’, vistas and beautiful, varied Mills, passed knee pain, shoulder landscapes continue to away after being pain, wasp stings, pointing at birds in the diagnosed at the amaze me. -

NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN AUGUST 2015 (Including Post Exam Modifications)

BOGNOR REGIS 2015—2030 NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN AUGUST 2015 (including post exam modifications) I THE REPORT IS MADE ACCESSIBLE AT THIS WEBSITE: WWW.BOGNORREGIS.GOV.UK/BR-TOWN-COUNCIL/NEIGHBOURHOOD_PLAN-16104.ASPX This document has been produced by Bognor Regis Town Council’s Neighbourhood Plan Committee with support from: Imagine Places, Royal Town Planning Institute/Planning Aid England, Locality, Integrated Urbanism, BPUD, the Prince’s Foundation for Building Community and - most importantly - the good people of Bognor Regis that have at various stages of the process so far contributed and helped to shape this plan. Disclaimer: This document is optimised for online viewing only. Please consider the environment before printing. Hardcopies are available for viewing at the Town Hall in Bognor Regis. II FOREWORD WELCOME TO THE BOGNOR REGIS NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN! Bognor Regis Town Council are very aware of the strength of feeling and loyalty towards the town and the oft-expressed view that many of its finer buildings have been lost over the years or replaced with ones of lesser architectural merit or inappropriately sited. The Town Council believe that having a Neighbourhood Plan in place will give local people much more say in the future planning of the town with regard to buildings and green spaces; their quality, look, feel, usage and location, as well as offering some protection to existing sites and buildings, much loved and valued by the community. The idea of Neighbourhood Plans initially came about because central government felt it important that local people had more of a say in what happened in their own town or village. -

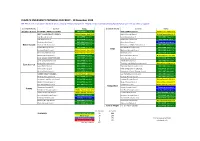

Progress Summary

CLIMATE EMERGENCY PROGRESS CHECKLIST - 10 December 2019 NB. This is work in progress! We have almost certainly missed some actions. Please contact [email protected] with any news or updates. County/Authority Council Status County/Authority Council Status Brighton & Hove BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL DECLARED Dec 2018 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed May 2019 WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed - April 2019 Ashford Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 Adur Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Canterbury City Council DECLARED July 2019 Arun District Council DECLARED Nov 2019 Dartford Borough Council DECLARED Oct 2019 Chichester City Council DECLARED June 2019 Dover District Council Campaign in progress West Sussex Chichester District Council DECLARED July 2019 Folkestone and Hythe District Council DECLARED July 2019 Crawley Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Gravesham Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Kent Horsham District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Maidstone Borough Council DECLARED April 2019 Mid Sussex District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Medway Council DECLARED April 2019 Worthing Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Sevenoaks District Council Motion Passed - Nov 2019 EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL DECLARED Oct 2019 Swale Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Eastbourne Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Thanet District Council DECLARED July 2019 Hastings Borough Council DECLARED Dec 2018 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 East Sussex Lewes District Council DECLARED July 2019 Tunbridge -

Word Version

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Adur in West Sussex Report to The Electoral Commission July 2002 THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2002 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report No: 306 2 THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? 5 SUMMARY 7 1 INTRODUCTION 11 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 13 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 17 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 19 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 21 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 37 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Adur is inserted at the back of this report. THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND 3 4 THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to The Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No. 3692). The Order also transferred to The Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

Notice of Variation: On-Street Parking Charges 2021 Arun District

WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL NOTICE OF VARIATION: ON-STREET PARKING CHARGES 2021 ARUN DISTRICT NOTICE is hereby given that West Sussex County Council in exercise of its powers under Section 46A Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 and Regulation 25 of the Local Authorities Traffic Order (Procedure) (England and Wales) Regulations 1996 proposes to vary the Charges and Tariffs detailed in the Second Schedule of the West Sussex County Council (Arun District) (Parking Places and Traffic Regulation) (Consolidation) Order 2010. The following charges will be changed as shown from 4 January 2021: Parking Permits: Old Charge New Charge Bognor Regis CPZ 1st Resident Annual Permit £44.00 £46.00 Subsequent Resident Annual Permit £88.00 £92.00 1st Resident 6-month Permit £24.00 £25.00 Subsequent Resident 6-month permit £48.00 £50.00 Non-Resident Annual Permit £275.00 £282.00 Non-Resident 6-month permit £145.00 £149.00 Countywide permits £25.00 £26.00 Pay and Display parking charges: Old Charge New Charge Town Per 30 mins Per Hour Per 30 mins Per Hour Centre Area £0.55 £1.10 £0.60 £1.20 Marine Per 30 mins Per Hour Per 30 mins Per Hour Drive West £0.30 £0.60 £0.35 £0.70 Esplanade Per 30 mins Per Hour Per 30 Mins Per Hour £0.55 £1.10 £0.60 £1.20 Dispensation Notices: Permit Areas in Arun: Old Charge New Charge CPZ Permit Areas £10.00 per day/£60.00 £11.00 per day/£66.00 per week per week Pay and Display Areas: Old Charge New Charge Bognor Regis Town Centre £14.00 per day/£84.00 £16.00 per day/£96.00 per week per week The Esplanade £15.00 per day/90.00 per -

Weather Broadcasts and Maritime Safety Information

Weather Broadcasts and Maritime Safety Information Her Majesty’s Coastguard is responsible in the UK for the broadcast of marine weather forecasts and Maritime Safety Information (MSI) on NAVTEX, VHF and MF and for providing the Radio Medical Advice Link Call (MEDILINK) Service. COVERAGE The primary method of disseminating MSI is by NAVTEX which provides coverage out to 270 miles. This service is complemented by radio telephony broadcasts. HM Coastguard provides VHF coverage out to 30 miles and MF coverage out to 150 miles using its network of remote aerial sites around the UK coast. Information about weather and MSI broadcasts from other European and worldwide national authorities can be obtained from: http://weather.gmdss.org/ NAVTEX Maritime Safety Information and additional weather information is transmitted by NAVTEX on 518 kHz in English at the following times: CULLERCOATS – 518 kHz (G) Gale warnings - when received and at: 0100 0500 0900 1300 1700 2100 24 hour forecast and outlook 0900 2100 Extended outlook (3-5 days) 0100 WZ navigation warnings 0100 0500 0900 1300 1700 2100 Tidal surge warnings – When received Navarea one warnings 0500 1700 NITON – 518 kHz (E) Gale warnings - when received and at: 0040 0440 0840 1240 1640 2040 24 hour forecast and outlook 0840 2040 Extended outlook (3-5 days) 0040 WZ navigation warnings 0040 0440 0840 1240 1640 2040 Tidal surge warnings When received SUBFACTS & GUNFACTS 0440 1640 Navarea One Warnings 0440 1640 PORTPATRICK - 518 kHz (O) Gale warnings - when received and at: 0220 0620 1020 1420 1820 2220 24 hour forecast and outlook 0620 1820 Extended outlook (3-5 days) 0220 WZ navigation warnings 0220 0620 1020 1420 1820 2220 SUBFACTS & GUNFACTS 0620 1820 Navarea one warnings 0220 1420 OOSTENDE - 518 kHz (T) Gale warnings (Dover & Thames) 0310 0710 1110 1510 1910 2310 Weather forecast 0710 1910 OOSTENDE - 518 kHz (V) Navigation warnings 0200 0600 1000 1400 1800 2200 Note: Weather information broadcast from this site is from Belgian sources not the Met Office. -

Adur District Council, Brighton & Hove City

ADUR DISTRICT COUNCIL, BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL, WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Notice of Publication and Statement of Representation Procedures Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 Proposed Submission Shoreham Harbour Joint Area Action Plan In accordance with the above regulations, this statement hereby gives notice that Adur District Council, Brighton & Hove City Council and West Sussex County Council (the authorities) are publishing and inviting comments on the Proposed Submission Shoreham Harbour Joint Area Action Plan. Representations are invited on the legal compliance and/or soundness of the document over the 6 week period from 10 November 2017 to 22 December 2017. During this period the proposed submission documents will be available for viewing. Following this publication period, the authorities intend to submit the Shoreham Harbour Joint Area Action Plan to the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government. The Proposed Submission Shoreham Harbour Joint Area Action Plan covers the Shoreham Harbour Regeneration Area, as identified in the Policy DA8 of the Brighton & Hove City Plan Part One (2016) and Policy 8 of the Submission Adur Local Plan (2017). These plans commit the councils to producing a Joint Area Action Plan for Shoreham Harbour. The Shoreham Harbour Joint Area Action Plan is a local plan setting out the authorities’ strategy for the regeneration of Shoreham Harbour and surrounding areas. The plan contains: • A long term vision, strategic objectives and strategy for the Shoreham Harbour Regeneration Area • Area-wide policies relating to each strategic objective • Proposals for seven character areas, including four allocations for development of new housing and employment generating floorspace • An outline of how the Shoreham Harbour Regeneration Project will be delivered, monitored and implemented. -

Agenda Item No 4 4 Minutes of the Meeting of the EAST KENT (JOINT SCRUTINY) COMMITTEE Held at the Council Offices, Whitfield On

Agenda Item No 4 Minutes of the meeting of the EAST KENT (JOINT SCRUTINY) COMMITTEE held at the Council Offices, Whitfield on Wednesday 25 April 2012 at 9.30 am. Present: Chairman: Councillor K Mills (Dover District Council) Councillors: B Copping (Shepway District Council) G Glover (Canterbury City Council) I Gregory (Thanet District Council) D Hannent (Dover District Council) G Lymer (Dover District Council) Z Wiltshire (Thanet District Council) Also Present: Director of Shared Services (EK Services) Officers: Chief Executive (Dover District Council) Solicitor to the Council (Dover District Council) Democratic Support Officer (Dover District Council) Apologies for absence were received from Councillors H Cragg, M Dance, C Goddard, D Green, J Holben, I Linfield, R Manning and M Vye. 13 ELECTION OF A CHAIRMAN It was proposed by Councillor G Lymer, duly seconded and RESOLVED: That Councillor K Mills be appointed Chairman for the duration of the meeting. 14 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest made by Members. 15 MINUTES The Minutes of the meetings of the Committee held on 25 January 2012 were approved as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. 16 OPERATING ARRANGEMENTS The Committee considered the operating arrangements. RESOLVED: That the operating arrangements be noted. 17 ISSUES REFERRED TO THE COMMITTEE BY THE EAST KENT (JOINT ARRANGEMENTS) COMMITTEE The Committee noted that at the meeting of the East Kent (Joint Arrangements) Committee (EKJAC) held on 14 March 2012 it had been resolved to undertake a review of the operating arrangements of the two East Kent committees, which would be reported to the next meeting. -

Agenda and Business

BOGNOR REGIS TOWN COUNCIL TOWN CLERK Glenna Frost, The Town Hall, Clarence Road, Bognor Regis, West Sussex PO21 1LD Telephone: 01243 867744 E-mail: [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam, ONLINE MEETING OF THE POLICY AND RESOURCES COMMITTEE I hereby give you Notice that an Online Meeting of the Policy and Resources Committee of the Bognor Regis Town Council will be held at 6.30pm on TUESDAY 19th JANUARY 2021 in accordance with The Local Authorities (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority Meetings) (England) Regulations 2020. All Members of the Policy and Resources Committee are HEREBY SUMMONED to attend for the purpose of considering and resolving upon the business to be transacted as set out hereunder. The public will not be permitted to speak during the Meeting. However, an opportunity will be afforded to Members of the Public to have Questions put, or make Statements to, the Committee during an adjournment shortly after the meeting has commenced. NB: All Questions and Statements MUST be submitted in writing (preferably by email) and MUST be received by the Town Clerk before 9am on Tuesday 19th January 2021. Online access to the Meeting will be via ZOOM using the following Meeting ID: 871-3245-3418. The meeting will also be streamed live to the ‘Bognor Regis Town Council’ Facebook page. DATED this 12th day of JANUARY 2021 TOWN CLERK AGENDA AND BUSINESS 1. Welcome by Chairman and Apologies for Absence 2. Declarations of Interest Members and Officers are invited to make any declarations of Disclosable Pecuniary and/or Ordinary Interests that they may have in relation to items on this agenda and are reminded that they should re- declare their Interest before consideration of the item or as soon as the Interest becomes apparent and if not previously included on their Register of Interests to notify the Monitoring Officer within 28 days. -

Census Joint Committee (Central Sussex Partnership)

CenSus Joint Committee (Central Sussex Partnership) Minutes of a meeting held in the Council Chamber, Civic Centre, Shoreham-by-Sea at 10.00am on Friday 19 June 2015 Present: Councillors: Neil Parkin (Chairman), Adur District Council Jim Funnell, Adur District Council Brian Donnelly, Horsham District Council Gary Marsh, Mid Sussex District Council Apologies: Councillors: Daniel Humphreys, Worthing Borough Council Mark Nolan, Worthing Borough Council Gordon Lindsay, Horsham District Council Jonathan Ash-Edwards, Mid Sussex District Council Also Present: Jane Eckford, Director for Customer Services, Adur and Worthing Councils Paul Brewer, Director for Digital & Resources, Adur and Worthing Councils Paul Tonking, Head of Revenues & Benefits, Adur and Worthing Councils Dave Briggs, Head of Design & Digital, Adur and Worthing Councils Neil Terry, Senior Democratic Services Officer, Adur and Worthing Councils Andrew Mathias, Senior Solicitor, Adur and Worthing Councils Katharine Eberhart, Director of Corporate Resources, Horsham District Council Tim Delany, Head of CenSus Revenues and Benefits, Mid Sussex District Council Peter Stuart, Head of Finance: CenSus CFO, Mid Sussex District Council John Ross, Head of CenSus ICT, Horsham District Council CJC/001/15-16 Declarations of Interest None. CJC/002/15-16 Minutes Resolved that the minutes of the meeting of the Committee held on 27 March 2015 be agreed and signed by the Chairman CJC/003/15-16 Urgent Items None. CJC/004/15-16 CenSus Annual Return 2014/15 The Committee received a report from the Head of Finance: CenSus CFO, setting out the CenSus Annual Return accounting statement for the partnership to be audited by PKF Littlejohn. The Committee was advised that the return fulfilled statutory requirements to report on the financial standing of the entity. -

SC1: South Coast Shoreline

Overall Character THE WEST SUSSEX LANDSCAPE Land Management Guidelines This long narrow Character Area extends between West Wittering and Shoreham and comprises the majority of the West Sussex coastline. It is a distinctive low, open and exposed landscape which has an overriding visual and physical association with the sea. Its wide and gently curved bays are further defined by the protruding shingle headland of Selsey Bill, and the chalk headland of Beachy Head in neighbouring East Sussex. This is a dynamic character area whose key characteristics are linked by coastal evolution, weather and tides. Sheet SC1 The character varies considerably according to weather condition and seasons. Key Characteristics G Relatively narrow undeveloped sections of coastline behind beaches. Bounded by low South Coast growing scant vegetation and small areas of wind-sculpted scrub and trees. Often G To the east of Selsey Bill, mainly shingle banks with bands of sand and mud exposed at providing separation of urban areas. Areas of both high ecological and landscape Shoreline low tide. importance. South Coast Plain G To the west of Selsey Bill, mainly sandy beaches, dry sand dunes and grassland habitats. G Shingle and sand dune habitats of national importance, notably at West Wittering, G Influence of extensive linear urban coastal resort development.To the east,almost Shoreham and Climping. The area covered by the Sheet is derived from: continuous conurbation of Bognor Regis, Littlehampton,Worthing and Shoreham.To the G Reed beds, streams and deep drainage ditches known as rifes. west, notably villages of West Wittering, East Wittering and Bracklesham. Separated by G Frequent wooden and rock groynes and breakwaters.