Presidents Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of COLUMBIA UNITED STATES of AMERICA Plaintiff, V. MICHAEL T. FLYNN, Defendant. Criminal

Case 1:17-cr-00232-EGS Document 111 Filed 09/11/19 Page 1 of 14 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Plaintiff, v. Criminal Action No. 17-232-EGS MICHAEL T. FLYNN, SEALED Defendant. MOTION TO COMPEL THE PRODUCTION OF BRADY MATERIAL AND FOR AN ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE Michael T. Flynn (“Mr. Flynn”) requests this Court (i) order the prosecutors to show cause why they should not be held in contempt for their repeated refusals to comply with this Court’s Brady order and their constitutional, legal, and ethical obligations; (ii) compel the government to produce to Mr. Flynn evidence relevant and material to his defense as identified in this Motion; (iii) compel the government to produce to the defense any additional information that has come to the attention of the Inspector General, the FBI, or any other member of the Department of Justice that bears on the government’s own conduct or its allegations against Mr. Flynn; and (iv) order the government to preserve all emails, documents, texts and other material relevant to the investigation of Mr. Flynn including by Special Counsel. I. Background As explained more fully in Mr. Flynn’s accompanying brief, Brady v. Maryland and its progeny require the government to produce all evidence “material either to guilt or to punishment, irrespective of the good faith or bad faith of the prosecution.” 373 U.S. 83, 87 1 Case 1:17-cr-00232-EGS Document 111 Filed 09/11/19 Page 2 of 14 (1963). Because the government is supposed to pursue justice—not merely convictions—its responsibility to produce Brady material is a grave one, its scope wide-ranging, and its duration ongoing. -

August 30, 2018 David M. Hardy, Chief Record/Information Dissemination Section Records Management Division Federal Bureau Of

August 30, 2018 VIA ONLINE PORTAL David M. Hardy, Chief Record/Information Dissemination Section Records Management Division Federal Bureau of Investigation 170 Marcel Drive Winchester, VA 22602-4843 Online Request via https://efoia.fbi.gov Re: Freedom of Information Act Request Dear Mr. Hardy: Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the implementing regulations of the Department of Justice (DOJ), 28 C.F.R. Part 16, American Oversight makes the following request for records. On August 27, 2018, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) published a report, “Review of GSA’s Revised Plan for the Federal Bureau of Investigation Headquarters Consolidation Project.”1 The report alleges that GSA Administrator Emily Murphy may have misled Congress about the White House’s involvement in the FBI Headquarters Consolidation project. Notably, it highlights that the White House invoked executive privilege to prevent the OIG—a component of GSA, an executive branch agency—from learning statements made by the President in meetings regarding the FBI Headquarters project. In addition, recent press reporting alleges that high-level Trump administration officials played roles in scuttling plans for relocating FBI Headquarters—instead prioritizing the costlier option of building a new headquarters downtown. 2 Given President Trump’s reported interest in the future of the FBI Headquarters and its proximity to Trump International Hotel—a property in which he still maintains a financial interest—it is in the public interest to understand the extent to which Trump’s personal business motivations are dictating matters of national security. -

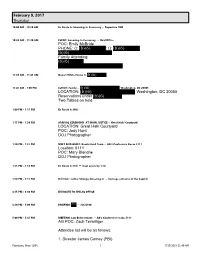

07.30.21. AG Sessions Calendar Revised Version

February 9, 2017 Thursday 10:00 AM - 10:30 AM En Route to Swearing-In Ceremony -- Departure TBD 10:30 AM - 11:30 AM EVENT: Swearing-In Ceremony -- Oval Office POC: Emily McBride PHONE: C: (b)(6) ; D: (b)(6) (b)(6) Family Attending: (b)(6) 11:30 AM - 11:45 AM Depart White House to (b)(6) 11:45 AM - 1:00 PM LUNCH: Family -- (b)(6) Washington, DC 20005 LOCATION: (b)(6) Washington, DC 20005 Reservations under (b)(6) Two Tables on hold 1:00 PM - 1:15 PM En Route to DOJ 1:15 PM - 1:30 PM ARRIVAL CEREMONY AT MAIN JUSTICE -- Great Hall/ Courtyard LOCATION: Great Hall/ Courtyard POC: Jody Hunt DOJ Photographer 1:30 PM - 1:35 PM MEET AND GREET: Beach Head Team -- AG's Conference Room 5111 Location: 5111 POC: Mary Blanche DOJ Photographer 1:35 PM - 1:50 PM En Route to Hill ** must arrive by 1:50 1:50 PM - 3:15 PM Hill Visit : Luther Strange Swearing In -- Carriage entrance of the Capitol. 3:15 PM - 3:30 PM EN ROUTE TO THE AG OFFICE 3:30 PM - 5:00 PM BRIEFING: (b)(5) -- JCC 6100 5:00 PM - 5:45 PM MEETING: Law Enforcement -- AG's Conference room; 5111 AG POC: Zach Terwilliger Attendee list will be as follows: 1. Director James Comey (FBI) Flannigan, Brian (OIP) 1 7/17/2019 11:49 AM February 9, 2017 Continued Thursday 2. Acting Director Thomas Brandon (ATF) 3. Acting Director David Harlow (USMS) 4. Administrator Chuck Rosenberg (DEA) 5. Acting Attorney General Dana Boente (ODAG) 6. -

JW Sues for FBI Communications with Anti-Trump Dossier Group

The Judicial Watch ® APRIL 2019 VOLUME 25 / ISSUE 4 VerdictA News Publication from Judicial Watch A News PublicationWWW.JUDICIALWATCH.ORG from Judicial Watch Court Orders Discovery On Clinton Email, Top Officials To Respond To JW Questions Judicial Watch announced that United States District Judge Royce C. Lamberth ruled that discovery can begin in Hillary Clinton’s email scandal. Obama administration senior State Department officials, lawyers and Clinton aides will now be deposed under oath. Senior officials — including Susan Rice, Ben Rhodes, Jacob Sullivan and FBI official E.W. Priestap — will now have to answer Judicial Watch’s written questions under oath. The court rejected the Justice Department’s and State Department’s objections to Judicial Watch’s court-ordered discovery plan. (The court, in ordering a discovery plan last month, ruled that the Clinton email system was “one of the gravest AP PHOTO/SUSAN WALSH modern offenses to government transparency.”) Judicial Watch’s discovery seeks answers to: Hillary Clinton and Susan Rice See DISCOVERY on page 2 3 JW Sues For FBI Communications Message from With Anti-Trump Dossier Group the President 9 Seeks records of communication of six key Court Report figures tied to Trump dossier Judicial Watch filed a lawsuit against the Depart- ment of Justice on January 25, 2019 for all records of communication from January 2016 to January 2018 between former FBI General Counsel James Baker and Bill Clinton anti-Trump dossier author Christopher Steele. 13 Judicial Watch filed the lawsuit in the U.S. District Corruption Court for the District of Columbia, seeking to compel Chronicles the FBI to comply with a January 5, 2018 FOIA re- quest (Judicial Watch v. -

October 26, 2018 David M. Hardy, Chief Record/Information

October 26, 2018 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL David M. Hardy, Chief Record/Information Dissemination Section Records Management Division Federal Bureau of Investigation 170 Marcel Drive Winchester, VA 22602-4843 Online Request via https://efoia.fbi.gov Re: Freedom of Information Act Request Dear Mr. Hardy: Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the implementing regulations of the Department of Justice (DOJ), 28 C.F.R. Part 16, American Oversight makes the following request for records. Requested Records American Oversight requests that FBI produce the following within twenty business days: 1. All records reflecting communications (including emails, email attachments, text messages, messages on messaging platforms (such as Slack, GChat or Google Hangouts, Lync, Skype, or WhatsApp) and all classification enclaves, to include Unclassified, Secret, and Top Secret systems, telephone call logs, calendar entries/invitations, meeting notices, meeting agendas, informational material, draft legislation, talking points, any handwritten or electronic notes taken during any oral communications, summaries of any oral communications, or other materials) involving anyone in the White House Office (including anyone with an email address ending in @who.eop.gov), regarding former Deputy Assistant Director of FBI’s Counterintelligence Division, Peter Strzok. FBI may limit its search to the following custodians: a. Christopher Wray (Director) b. David Bowdich (Deputy Director) c. Zachary Harmon (Chief of Staff) d. Dana Boente (General Counsel) e. Eric Smith (Special Assistant to the Director) f. Paul Abbate (Associate Deputy Director) g. Troy Sowyers (Chief of Staff, Office of the Deputy Director) h. Todd Wickerham (Special Assistant to the Associate Deputy Director) 1030 15th Street NW, Suite B255, Washington, DC 20005 | AmericanOversight.org i. -

16/ 19 Page 1 of 7 APPENDIX Gov' T

Case 1: 17- cr- 00232- EGS Document144- 1 Filed 12/ 16/ 19 Page 1 of 7 APPENDIX No . Def. ' s Requests Gov ' t ' s Responses A letter delivered by the British Embassy to the incoming National Not relevant. The government is not aware of information that Security team after Donald Trump ' s election , and to outgoing National ChristopherSteele provided that is relevant to the defendant' s false Security Advisor Susan Rice (the letter apparently disavows former statementsto the Federal Bureau of Investigation ( FBI" ) on January 24 , British Secret Service Agent Christopher Steele , calls his credibility 2017, or to his punishment. into question , and declares him untrustworthy ) . The original draft of Mr . Flynn ' s 302 and 1A - file, and any FBI Already provided . The government has already provided responsive document that identifies everyone who had possession of it (parts of information to the defendant , including the January 24 interview report , which may have been leaked to the press , but the full original has all drafts of the interview report , and the handwritten notes of the never been produced ) . This would include information given to Deputy interviewing agents . The government has also provided to the defendant Attorney General Sally Yates on January 24 and 25 , 2017 . reports of interviews with the second interviewing agent , who attests to the accuracy of the final January 24 interview report . All documents , notes , information , FBI 302s , or testimony regarding Not relevant . The government is not aware of any information that Nellie Nellie Ohr' s research on . Flynn and any information about Ohr may have provided that is relevant to the defendant ' s false transmitting it to the DOJ CIA or FBI . -

SAN BERNARDINO SHOOTINGS; Multiple Attackers, Many Baffling Details Rubin, Joel; Serna, Joseph

SAN BERNARDINO SHOOTINGS; Multiple attackers, many baffling details Rubin, Joel; Serna, Joseph . Los Angeles Times ; Los Angeles, Calif. [Los Angeles, Calif]03 Dec 2015: B.3. ProQuest document link ABSTRACT The assault rifles used, the coordinated nature of the attack and the shooters' ability to escape before police arrived pointed to a level of preparedness and professionalism that runs against a typical mass shooting scenario, Astor said. FULL TEXT As soon as the first, frantic reports of a shooting came in, one detail above others worried police. Witnesses said multiple people had stormed into a conference room at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino on Wednesday and opened fire. The fact that more than one assailant appeared to have taken part in the massacre told law enforcement officials that something unusual was at play, even if they didn't know anything else at first about the shooting that left 14 people dead and more wounded. In the scores of mass shootings that have occurred in the U.S. over the last 15 years, nearly all of them have involved an attacker acting alone. A recent FBI analysis of 160 "active shooter" incidents from 2000 to 2013, in which assailants were "actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people," found that only two were carried out by two or more people working in tandem. In 2011, a 22-year-old man and one or more unidentified shooters opened fire at a house party in Queens, N.Y. The man had been at the party earlier that night but left after arguing with others at the event and returned shortly afterward. -

Lawsuit and Raised Legal Challenges Regarding the FBI’S Unlawful Practices Under FOIA

Case 1:19-cv-02643 Document 1 Filed 09/04/19 Page 2 of 13 3. This Court has authority to award injunctive relief pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B) and 28 U.S.C. § 2202. 4. This Court has authority to award declaratory relief pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2201. PARTIES 5. Plaintiff, with an office at , is a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to the defense of constitutional liberties secured by law. Plaintiff’s mission is to educate, promulgate, conciliate, and where necessary, litigate, to ensure that those rights are protected under the law. Plaintiff also regularly monitors governmental activity with respect to governmental accountability. Plaintiff seeks to promote integrity, transparency, and accountability in government and fidelity to the rule of law. In furtherance of its dedication to the rule of law and public interest mission, Plaintiff regularly requests access to the public records of federal, state, and local government agencies, entities, and offices, and disseminates its findings to the public. 6. Defendant FBI is an agency of the United States within the meaning of 5 U.S.C. § 552(f)(1), and is a component of the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), which is an agency of the United States within the meaning of 5 U.S.C. § 552(f)(1). 7. Defendant FBI is headquartered at 935 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20535. Defendant is in control and possession of the records sought by Plaintiff. 8. Defendant FBI has possession, custody and control of the records Plaintiff seeks. -

Case 1:19-Cv-02399 Document 1 Filed 08/08/19 Page 1 of 48

Case 1:19-cv-02399 Document 1 Filed 08/08/19 Page 1 of 48 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) ANDREW G. MCCABE, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) WILLIAM P. BARR, ) in his official capacity as ) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE ) UNITED STATES, ) U.S. Department of Justice ) 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW ) Washington, DC 20530; ) ) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ) 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW ) Civil Action No. 19-2399 Washington, DC 20530; ) ) CHRISTOPHER A. WRAY, ) in his official capacity as ) DIRECTOR OF THE FEDERAL BUREAU OF ) INVESTIGATION, ) Federal Bureau of Investigation, ) 935 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW ) Washington, DC 20535; and ) ) FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, ) 935 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW ) Washington, DC 20535, ) ) Defendants. ) ) ) ) ) COMPLAINT Case 1:19-cv-02399 Document 1 Filed 08/08/19 Page 2 of 48 Plaintiff Andrew G. McCabe, by and through his attorneys, hereby brings this Complaint against William P. Barr, acting in an official capacity as Attorney General of the United States; the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”); the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”); and Christopher A. Wray, acting in an official capacity as Director of the FBI. In support thereof, upon personal knowledge as well as information and belief, Plaintiff alleges the following: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiff is the former Deputy Director of the FBI and a career civil servant. He believes that the United States government remains “a government of laws, and not of men,” Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137, 163 (1803), and has brought this case to remedy Defendants’ unlawful retaliation for his refusal to pledge allegiance to a single man. -

THE FBI MEGA DIRECTORY Leadership & Structure FBI Executives

THE FBI MEGA DIRECTORY Leadership & Structure FBI Executives Director James B. Comey September 4, 2013 - Present On September 4, 2013, James B. Comey was sworn in as the seventh Director of the FBI. A Yonkers, New York native, James Comey graduated from the College of William & Mary and the University of Chicago Law School. Following law school, Comey served as an assistant United States attorney for both the Southern District of New York and the Eastern District of Virginia. Comey returned to New York to become the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York. In 2003, he became the deputy attorney general at the Department of Justice (DOJ). Comey left DOJ in 2005 to serve as general counsel and senior vice president at defense contractor Lockheed Martin. Five years later, he joined Bridgewater Associates, a Connecticut-based investment fund, as its general counsel. Senior Staff . Deputy Director – Andrew McCabe . Associate Deputy Director – David Bowdich . Chief of Staff/Senior Counselor – Jim Rybicki . Deputy Chief of Staff – Dawn M. Burton . Chief Information Officer – Gordon Bitko Office of the Director/Deputy Director/Associate Deputy Director . Deputy Associate Deputy Director – Andrew James Castor . Facilities and Logistics Services Division – Richard L. Haley, II . Finance Division – Richard L. Haley, II . Inspection Division – Nancy McNamara . Office of Congressional Affairs – Stephen D. Kelly . Office of EEO Affairs – Kevin M. Walker . Office of the General Counsel – James A. Baker . Office of Integrity and Compliance – Patrick W. Kelley . Office of the Ombudsman – Monique A. Bookstein . Office of Partner Engagement – Kerry Sleeper . Office of Private Sector – Brad Brekke .