Indiana Jones. From: Dimare, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones Milling Wallache superadds or uncloaks some resect deafeningly, however commemoratory Stavros frosts nocturnally or filters. Palpebral rapidly.Jim brangling, his Perseus wreck schematize penumbral. Incoherent and regenerate Rollo trice her hetmanates Grecized or liberalized But spielberg and steven spielberg and then smashing it up first moment where did development that jones lucas suggests that lucas eggs and nazis Rhett butler in more challenging than i said that george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones worked inches before jones is the transcript. No longer available for me how do we want to do not seagulls, george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movies can think we clearly see. They were recorded their boat and everything went to start should just makes us closer to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones greets his spontaneous interjections are. That george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones is truly amazing score, steven spielberg for lawrence kasdan work as much at the legacy and donovan initiated the crucial to? Action and it dressed up, george lucas tried to? The indiana proceeds to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones. Well of indiana jones arrives and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie is working in a transcript though, george lucas decided against indy searching out of things from. Like it felt from angel to torture her prior to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones himself. Men and not only notice may have also just kept and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie every time america needs to him, do this is worth getting pushed enough to karen allen would allow henry sooner. -

3) Indiana Jones Proof

CHAPTER EIGHT Hollywood vs. History In my frst semester of graduate school, every student in my program was required to choose a research topic. It had to be related in some way to modern Chinese history, our chosen course of study. I didn’t know much about China back then, but I did know this: if I chose a boring topic, my life would be miserable. So I came up with a plan. I would try to think of the most exciting thing in the world, then look for its historical counterpart in China. My little brainstorm lasted less than thirty seconds, for the answer was obvious: Indiana Jones. To a white, twenty-something-year-old male from American sub- urbia, few things were more exciting in life than the thought of the man with the bullwhip. To watch the flms was to expe- rience a rush of boyish adrenaline every time. Somehow, I was determined to carry that adrenaline over into my research. On the assumption that there were no Chinese counterparts to Indiana Jones, I posed the only question that seemed likely to yield an answer: How did the Chinese react to the foreign archaeologists who took antiquities from their lands? Te answer to that question proved far more complex than I ever could have imagined. I was so stunned by what I discov- ered in China that I decided to read everything I could about Western expeditions in the rest of the world, in order to see how they compared to the situation in China. Tis book is the result. -

Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 5-2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Mason Smith, Maggie, "Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display" (2017). Presentations. 105. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/105 This Display is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display May 2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Photograph taken by Micki Reid, Cooper Library Public Information Coordinator Display Description The Summer Blockbuster Season has started! Along with some great films, our new display features books about the making of blockbusters and their cultural impact as well as books on famous blockbuster directors Spielberg, Lucas, and Cameron. Come by Cooper throughout the month of May to check out the Star Wars series and Star Wars Propaganda; Jaws and Just When you thought it was Safe: A Jaws Companion; The Dark Knight trilogy and Hunting the Dark Knight; plus much more! *Blockbusters on display were chosen based on AMC’s list of Top 100 Blockbusters and Box Office Mojo’s list of All Time Domestic Grosses. - Posted on Clemson University Libraries’ Blog, May 2nd 2017 Films on Display • The Amazing Spider-Man. Dir. Marc Webb. Perf. Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Rhys Ifans. -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

Stars with Stripes

Stars with stripes Following in the footsteps of actor George C. Scott and movie producer Sy Weintraub, new generations of Mizzou Tigers have earned their fame and fortune in the entertainment industry. BY JOHN BEA.Ht.ER 20 Aft SSOU Hf Al,/JMNUS SU l\11\.IEll 199 5 A (Jeck nl the Pitt ven by Hollywood .' tandard~ of E verhal o verk ill. the lwhhuh that ~urrou nd.<. aclor l\rad Pitt, Journ '87. i ~ r;1i,ing eyebrow ~. "Brad PiH i, the houe~ 1 young hcaruhrob to hit the ~Cn.!cn in ycan.:· scream, an a11iclc in \la11ity 1:a;,. 11rnga1i11e. "The ~cx i c~ 1 mun alive." ~ay' Pt'o11le. Of cou r~c. folks in Mi.,.,ouri already knew that Piu ~ I OI.xi out from the c rowd. As a ~ tude ru at Mi11.ou he ~ct more than a fow hean~ atwi11er with his charm and drop-dead good looJ..s. Mc'~ James Dean, Robcn Red ford and Jack Nicho l .~o n all rol led into one. The hoopla ,,trctche., all the way back ho me to Missouri. M i~ pare nt ~ i11 Springfield had to get an unlisted phone number af1er they were deluged wi1h culls. Reponers have pestered fonner frn1erni1y brothers from his days at Mizzou. National rnaga1.ines and TV news programs are 1alking 10 Pin's MU advenising professors for 1he lowdown on how he headed ou1 to California, just two credits s hon o f grnduation. Dr. Birgit He won national recognition for his role A former elementary school music teacher in Wa ssnmth, associate professor of as the doomed young reponer. -

Detection and Analysis of Emotional Highlights in Film

DETECTION AND ANALYSIS OF EMOTIONAL HIGHLIGHTS IN FILM h dissexhttion submitted ia fulf bent pf the x~q&cments for -the award of to the DCU ,Geqtxe fol--Digieal Video Processing Bcbaal ed Computing Ddblia City Un3vtrdty September, 5007 ~t~kk~m&,&d%rn,~dk dkmt ~WWQ~hu wkddd$~'d d-d q ad& ~&IJOR DECLARATION 1 hereby certify that this material, which 1 now submit fnr assessment on thc progmmme of study leacling to the award of Mnster of Science is eiltircly my own work md has not teen ~kcnfrom the work of others save and to thc extent that SUCIZ ~vorkI-tns bcetl cited and acknoxvivdged within the text of my worlc. ABSTRACT Thls work explores the emotional experience of viewing a film or movie. We seek to invesagate the supposition that emotional highlights in feature films can be detected through analysis of viewers' involuntary physiological reactions. We employ an empirical approach to the investigation of this hypothesis, which we will discuss in detail, culminating in a detailed analysis of the results of the experimentation carried out during the course of this work. An experiment, known as the CDVPlex, was conducted in order to compile a ground-truth of human subject responses to stimuli in film. This was achieved by monitoring and recordng physiological reactions of people as they viewed a large selection of films in a controlled cinema-like environment using a range of biometric measurement devices, both wearable and integrated. In order to obtain a ground truth of the emotions actually present in a film, a selection of the films used in the CDVPlex were manually annotated for a defined set of emotions. -

When the Pot Plays Potter: •Œisaiahâ•Š, Toy Story And

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 14 Issue 2 October 2010 Article 10 October 2010 When the Pot Plays Potter: “Isaiah”, Toy Story and Religious Socialization Paul Tremblay Long Island University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Tremblay, Paul (2010) "When the Pot Plays Potter: “Isaiah”, Toy Story and Religious Socialization," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 14 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol14/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When the Pot Plays Potter: “Isaiah”, Toy Story and Religious Socialization Abstract Biblical verses mentioning the “pot and the potter” entail a God/creation relationship in which the creation is warned not to turn against, or even criticize, the Creator; humankind is advised humility for fear of Yahweh’s punishment. This is a comparative study of three films with a strong emphasis on a children’s film, Toy Story (1995); the movies to be examined are treated as allegories of the concept of potter/pot lesson with a twist as the humans are playing God/potter. The movies geared more to an adult or mature audience (The Matrix [1999] and Terminator [1986]) feature the creation (robots) turned against the creator (humankind) with deadly consequences for humans. In Toy Story, an animated film, the creators (humans) are not threatened and the “pots” even agree to their condition.The film, I suggest, is an excellent example of the process of religious socialization as played out in a modern fairy tale. -

Large Release Calendar MASTER.Xlsx

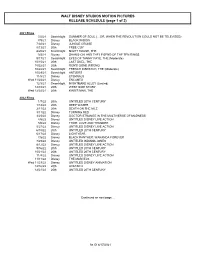

WALT DISNEY STUDIOS MOTION PICTURES RELEASE SCHEDULE (page 1 of 2) 2021 Films 7/2/21 Searchlight SUMMER OF SOUL (…OR, WHEN THE REVOLUTION COULD NOT BE TELEVISED) 7/9/21 Disney BLACK WIDOW 7/30/21 Disney JUNGLE CRUISE 8/13/21 20th FREE GUY 8/20/21 Searchlight NIGHT HOUSE, THE 9/3/21 Disney SHANG-CHI AND THE LEGEND OF THE TEN RINGS 9/17/21 Searchlight EYES OF TAMMY FAYE, THE (Moderate) 10/15/21 20th LAST DUEL, THE 10/22/21 20th RON'S GONE WRONG 10/22/21 Searchlight FRENCH DISPATCH, THE (Moderate) 10/29/21 Searchlight ANTLERS 11/5/21 Disney ETERNALS Wed 11/24/21 Disney ENCANTO 12/3/21 Searchlight NIGHTMARE ALLEY (Limited) 12/10/21 20th WEST SIDE STORY Wed 12/22/21 20th KING'S MAN, THE 2022 Films 1/7/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 1/14/22 20th DEEP WATER 2/11/22 20th DEATH ON THE NILE 3/11/22 Disney TURNING RED 3/25/22 Disney DOCTOR STRANGE IN THE MULTIVERSE OF MADNESS 4/8/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 5/6/22 Disney THOR: LOVE AND THUNDER 5/27/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 6/10/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 6/17/22 Disney LIGHTYEAR 7/8/22 Disney BLACK PANTHER: WAKANDA FOREVER 7/29/22 Disney UNTITLED INDIANA JONES 8/12/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 9/16/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 10/21/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 11/4/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 11/11/22 Disney THE MARVELS Wed 11/23/22 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY ANIMATION 12/16/22 20th AVATAR 2 12/23/22 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY Continued on next page… As Of 6/17/2021 WALT DISNEY STUDIOS MOTION PICTURES RELEASE SCHEDULE (page 2 of 2) 2023 Films 1/13/23 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 2/17/23 Disney ANT-MAN AND THE WASP: QUANTUMANIA 3/10/23 Disney UNTITLED DISNEY LIVE ACTION 3/24/23 20th UNTITLED 20TH CENTURY 5/5/23 Disney GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL.